Hospital Drama: “Cook or We’re Done!” Husband’s Shocking Demand and His Mom’s Epic Response!

Part One

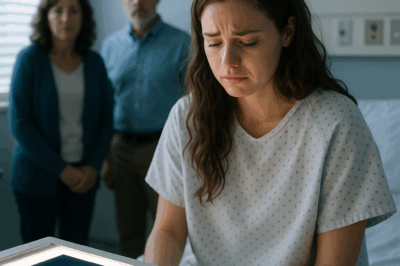

The words came through my phone like a slap. I had been lying on a narrow hospital bed, windows pulled tight against the winter, a roommate snoring softly next door and the antiseptic smell making everything feel unreal. The doctor had spoken in gentle, careful sentences about fractures and recovery timelines; my mumbling acceptance had been more posture than comprehension. Then the phone pulsed on the bedside table and his name lit the screen.

“Come home and make dinner or we’re done,” he barked into my ear as if I were a ringing toaster and not a person with two broken bones and a pulse that trembled with pain. His laugh at the end of the sentence was the sound of someone who had rehearsed cruelty and found it easy.

For a moment I was so stunned I thought I had missed something—had I misheard, did he mean something else? But the evidence was cold and unambiguous: he wanted me to leave my own hospital bed, hobble home, and cook, and if I refused, he would end our marriage.

The man on the phone, my husband Matt, had been easy to love in the small, deliberate ways at the beginning. He courted me with predictable tenderness: surprise café dates, warm messages on slow afternoons, the kind of humor that unfolded across my nervousness and made it all feel possible. We had built a life together while busy with jobs and future plans. We made lists. We spoke of splitting chores equally because both our careers mattered. At the wedding we smiled and promised forever in the way people who are generous with each other’s shadows do.

Then life, like weather, changed its pattern. The small shifts arrived almost politely—late nights at the office, a decreasing interest in household work, an ease at letting dinner burn because someone else would “handle it.” I noticed each step and showed patience until patience felt like a garment that didn’t fit me anymore. I tried to talk to him; he called me nagging, tone blunt and dismissive. Once, over a laundry pile, he told me that some chores were “women’s work.” It was a line I had heard in someone else’s life; I had never expected it to land on mine.

The fracture in the subway was mundane enough—one of those unremarkable injuries that reorder a life in a single instant: a slippery step, a missed hold, a loud crack as my ankle betrayed me. I remember only flashes: the world tilting; strangers’ hands, efficient and concerned; a policeman asking my address as if I were already a scene; the ambulance’s muffled hum. And then the hospital, with everything reduced to medical terms and a clean, waiting bed.

When Matt called I clung to the hope that he would come quickly, the way some men do when their alarm clamps them into urgency. When he told me to get up and cook, I tasted cold and felt the ridiculousness of a marriage that had become a ledger of obligations rather than a partnership. I felt absurd in a place designed to help, and yet the absurdity made the cruelty feel sharper.

I must have gone pale because a nurse came in, checked my vitals and murmured something about keeping my leg elevated. I handed the phone to a neighbor in the next bed and let her listen to the ending of our relationship.

What I hadn’t expected was the sound of slippers in the corridor and the surprised, breathless voices of people who had not been in my life much, but who clearly had been worried enough to come: Matt’s parents.

They entered the room like two characters who had been called back into a play they thought they’d already finished. Their presence was not theatrical; it was quiet, practical worry. My father-in-law’s hands were big and gentle; my mother-in-law’s eyes were rimmed with sympathy. They had come because the office—my workplace, which had notified them—had believed they were the emergency contact listed for Matt. When the office couldn’t reach him, someone had called the Johnsons. And they had hurried.

I remember how small the world seemed in that moment—my husband’s absence a loud hole and his parents’ faces an expression I had not expected, not the smug indifference of his calls but a rarity: real concern. They fussed like people who cared about the fruit of someone’s life; they asked about pain and transport and the comfort of an ice pack. They spoke in the cadence of people who had been crossed by the same life decades ago and had learned to hurry to its minor catastrophes.

When Matt called again, more furious than before, his parents listened, and in their faces I read something like betrayal—not at me, but at him. “How could you say that to her?” my mother-in-law demanded, her voice close to trembling on the line. “You will come right now and you will apologize.”

His protest was sputtering small and easy. He tried to blame me—said the hospital staff had called the wrong number, that I had exaggerated, that perhaps I’d drunk too much—stuff he considered childish and dismissible. I handed the phone over and let them speak for me. I watched them become furious in a way that felt cleansing. Parents who knew the young man’s edges now looked at him as if seeing a stranger who had been masquerading as their son. Shame didn’t fall like snow; it fell like a judgmental weight.

“What you said is unforgivable,” Mr. Johnson said carefully, each word slow as a hammer. “You don’t speak to your wife like that. Not when she is hurt. Not ever.”

My husband, who had always swanned between charm and entitlement, suddenly looked like a child with a skinned knee. He stammered soft excuses, but the line of his defenses had broken.

With the Johnsons’ fierce defense behind me, something opened: not a magical reconciliation, but a clearing. They came to sit with me in the hospital, bringing paper-wrapped sandwiches and an absurdly small vase of wildflowers. They stayed until visiting hours ended. Their presence was not a theatrical claim on my property or a desperate plea for moral rightness; it was practical solidarity. They did what adults do when they see childish cruelty: they called it out and took me somewhere safe.

By the time I was discharged, Matt had been summoned by them to conversations he could not thread into charm. He had to face the blunt reality that marriage, when pushed to its edges, demands more than a performative promise. He had also been forced to consider how his absence and his blunt directives had alienated those who might have once tolerated his nonsense.

When I left the hospital, the Johnsons helped me home, carrying the small things that make recovery less raw: a bag of ergonomic pillows, the remote controls arranged where I could reach them, a thermos of soup. It was an unexpected tenderness, arriving from the people who should have always been on my side but who, for years, had been kept at a certain polite distance.

At home, there were things to address. Pain and recovery are not just physical; they rearrange the contract of a household. Once I had the bandage and the high table and the appointed visits from the physiotherapist on the calendar, I had to turn to the emotional arithmetic as well.

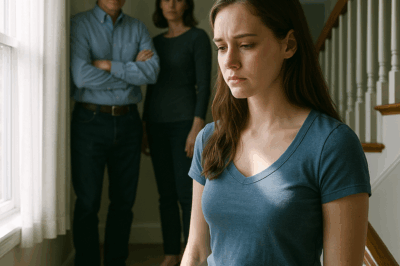

Matt tried, in the first days, to apologize and be competent. For a few minutes he showed the kind of competence I could have trusted—he tied my shoelaces, brought in the mail, made coffee. But the old habits were stubborn. Within a week, the easy resentments returned: little passive remarks when I didn’t reach the remote, the old suggestion that I should “manage my time better.” The Johnsons, however, had been changed by what they’d seen. They now called him out not with gentle nudges but with an unforgiving clarity.

“What you said was cruel,” Mrs. Johnson told him at dinner the night after I came home. “That woman is here, hurt and trusting you, and you told her to cook. You have to do better.” Her eyes did not soften; they sharpened into lines that felt like truth.

That confrontation began, in small steps, a kind of unfastening. Matt could no longer rely on a safety net of permissiveness. He had, perhaps for the first time, to meet accountability from the people who loved him enough to stop enabling him. For me, the Johnsons’ fierce advocacy was a revelation—a new map that showed where allies might be found in familiar faces.

But the fissure did not mend instantly. Marriage sewn with thin threads does not heal overnight, and promises that had lived mostly on habit needed to be renovated into practice. I found myself both grateful and wary. Grateful that my in-laws chose me when he’d been cruel; wary that such a change could be superficial if not accompanied by a deeper willingness to shift.

As I healed and attended physiotherapy sessions, I observed Matt’s attempts to change like the slow thaw of a river. Some days he arrived with flowers and with small chores completed without my asking. Other days his temper reasserted itself in minor digs and the old arrogance that had once seemed like confidence but now read like entitlement. The Johnsons watched it all with the tired patience of people who knew that the intention to change is only as useful as its follow-through.

One evening, after an especially good therapy session, I made myself toast in a pan on the small stove my mother-in-law insisted we keep clean and ready. Matt didn’t help; he sat with his laptop open and watched football highlights. I felt the old resentment tighten for a moment, and then I remembered a moment in the hospital: his parents’ voices on the phone, telling him that cruelty is unforgivable. I folded the heat of it around myself like a reminder that I had allies.

But the story does not pivot on a single upright decision; it bends with the weather of repeated choices. When I told him I wanted us to speak to a counselor together because apparently two people cannot rebuild a partnership without someone guiding the conversation, he balked. “Why drag a stranger into our life?” he asked. When I insisted, he said he would stop certain behaviors, but he wanted time.

Time, I realized, had become his refuge—a way to postpone the friction of necessary change. And for me, with a healing leg and a newfound clarity that my dignity couldn’t be a footnote in someone else’s convenience, patience had to be measured against consequence. If change were real, it would be visible and consistent. If it were performative, the damage would continue.

Part Two

Months are strange creatures. They can be a patient spinal of tiny choices that, stacked, become a life. The arc of our marriage in those months began to reveal what we truly prioritized. Matt tried and sometimes succeeded in showing better behavior, but his commitment to transformation was episodic. With a job that continued to demand long, lurching hours, and with an old habit of defaulting to convenience he had always favored, his worst patterns kept returning.

Counseling sessions were like mirrors; they reflected things neither of us had liked to see. He learned to call before making plans; he learned to do a laundry load without being told; he learned what it felt like to be accountable for the small logistics of a shared life. I learned how to express my limits without launching into accusations that would make his defenses flare. For a while, we were two people at a construction site, building a bridge with piles of the same materials we’d ignored before.

But repair requires a kind of mutual will. I began to see that while I was willing to rebuild, his willingness fluctuated. At times, I was left holding all the continuity like a table that only I propped up. It was not fair, and fairness is not a lofty word in marriage—it is the practical calculus of who clears the dishes when the TV is still on, of who answers the tiredness when someone needs help. For a person who professed love, the small dutiful thermoses of kindness should be obvious.

Finally, with a clarity that came from too many half-promises and a full diagnosis of my own limits, I made a choice. If he wanted to be my partner, change had to be consistent and enduring. If he could not, then staying meant living with a permanent undersupply of respect. Change, in other words, could not be a theatrical act performed on the night of discovery and then folded away the next week.

I told him gently, and then more firmly, that the marriage needed a clear contract: consistent household contributions, shared calendar responsibilities, and couples therapy with regular attendance. He listened and agreed. For five weeks he practiced better behavior. For two months, he showed up. The Johnsons—my in-laws, who had come to my aid in that first awful hour—watched as if guarding a fragile seedling. They encouraged his progress with the hopeful fatigue of people who have seen many storms.

But then old impulses returned with the insidious cleverness of habit. One morning, when I had a presentation at work and had stayed up late designing slides, I came home to a pile of dirty dishes and a television on. He offered a casual apology and then asked me to be patient. It was, I realized with a sinking clarity, that he could be kind in patches but could not consistently be the partner I needed.

So we made a hard call. It was not a spectacular fight with flung plates or a courtroom scene. It was a meeting between adults who had loved each other enough to try but who realized that compatibility is practical. We signed papers with measured hands, dividing savings and deciding logistical things for the future. Mr. and Mrs. Johnson held my hand in the lawyer’s office and told me we were being brave in a way that didn’t involve theater.

There were consequences, of course. For Matt, life got narrower in some predictable ways. He had to learn laundry and nutrition and how to negotiate his own habits without the ease of a ready partner who would shoulder them without question. At his office, the whispers started: attendance issues, personal upheaval. People who had once thought him charming noticed that charm could not replace functionality. The new wife—if there was one—did not have a romantic ability to rewrite the past.

I, for my part, found a deeper steadiness in the small choices that shaped everyday life. I returned to work and completed the slides that mattered. I attended physiotherapy and watched my mobility return with steady discipline. The Johnsons stopped seeing me as an intruder in their son’s life and began to be the kind of family who came to dinner and didn’t expect extractive gratitude. They had been my bridge when his voice had been callous; now they became friends.

A year after the fracture, on a rainy afternoon that smelled of wet pavement and fresh coffee, I made my first truly solitary meal in our kitchen. It was simple: roasted vegetables, a small piece of herbed chicken, rice. I set the table with two plates not out of loneliness but out of learned habit—two plates once meant we shared burdens and joys. Now the second plate was symbolic for someone else to join me later, or not. I ate alone, and the taste of my independence was not bitter but candid and oddly sweet.

I began to do little things for myself that had nothing to do with the story of my marriage. I joined a yoga class that met in the evenings; I started a small blog about simple, practical recovery recipes to help people who were stuck at home with limited mobility. My writing attracted a few kind readers—women who shared tips about splints and dinners and the value of asking for help. I learned to accept assistance without feeling diminished.

Months turned to years, and the memory of that phone call—the one where he told me to cook or face divorce—became a marker of a past life rather than a present wound. The husband who had made that threat was not grotesquely punished by fate; instead, he navigated consequences—legal, social, and internal—that eroded the reckless ease he had once enjoyed. He learned practical humility as he learned how to fold laundry, budget meals, and eat food he did not cook.

One evening, as the country warmed toward spring, I hosted the Johnsons for dinner in my modest kitchen. We laughed over a mishap with a recipe; Mr. Johnson told a clumsy joke; Mrs. Johnson passed the salad. No big statements were needed. What had been built in breakfasts and hospital visits and in the slow work of repair was an ordinary grace that I hadn’t expected to receive but had been given anyway.

People sometimes ask whether I forgave my ex. Forgiveness, I have learned, is not a singular event; it is a practice of reconfiguring expectations. I forgave him in the sense that I no longer carried him as the axis of my worth. But I did not forget the lessons his cruelty taught me: that rights and dignity are earned in daily practice, not declared by men who enjoy the comforts of being adored.

And then, in a place carefully outside of any melodrama, something gentle entered my life: a person named Sam, who had the steady patience of a gardener and the wry humor of someone who had fallen by accident into being kind. He saw me as a whole person—my scars included—and asked small, sensible things: “Can I bring you a casserole on Tuesday?” or “Do you prefer tea or coffee in the morning?” He asked, and then he listened to the answer and acted.

We did not leap into a marriage scripted by dramatic reparations. We walked slowly, measured the seam between us, and discovered that respect can bloom into affection when given proper room. Perhaps the greatest gift the fracture gave me was a softer recognition: the ability to say no, to demand steadiness, to let go of a convenient charm and choose a patient partnership.

One cold winter night, two years from the hospital call that had been both the beginning of the end and a fierce hinge in my life, I hung a new photograph on the wall by the kitchen. It was small—my hand in Sam’s, both of us holding a paper map of a place we had traveled to; behind us, buildings and people and the messy life of a city forgiving itself. The photograph was simple and ordinary, a proof that the life I had chosen could be both safe and surprising.

I sometimes think about the thing people call heroic revenge—the dramatic scenes illusions write. But my story’s real triumph was quieter: the old outrage was replaced by an honest life. Not triumphant in headlines or loud vindication, but triumphant in the way a restored window keeps the rain out. The Johnsons and I became a family whose measure was taking care, not taking advantage.

The man who had once told me to make dinner or be cast away had to learn that marriage is not a thermostat you control by shouting. He had to sit with his choices, with an existence reconstituted without the easiest comforts. He might have learned humility; he might have remained stubbornly unapologetic. What matters is that I lived, whole, and learned to trust the people who offered steady kindness over performative charm.

On the day I closed the small recipe blog with an entry about oatmeal cookies for comfort and healing, I wrote this sentence at the end: “You will find that dignity is not a scarce resource; it is something you practice, with small acts, until you wake up one morning and it is the furniture of your life.” I signed it with my name and, for once, did not feel dramatic about it.

In the kitchen that evening, with the window cracked and the sound of a radio humming a song I had always liked, I made dinner for simple people: Sam, my in-laws, and me. We ate slowly and talked about trivial things—work deadlines from years ago, a neighbor’s strange cat, the weather the children asked about when they were small. There was no need to dramatize the past or to litigate wounds that had already had their trial.

When the dishes were stacked and the lights dimmed low, I cleaned the counters and paused. The hospital, the fracture, the phone call—all of it belonged to a season. Seasons change. People change. I had chosen to change too. The last thing I did before heading to bed was send a small, practical message to Sam: “Don’t forget your umbrella.” He replied with a smiling emoji, and the smallness of it felt enormous.

The door to the life I had been given by fate and hard choice had opened again—not because someone had pushed me through, but because I had learned how to step forward on my own two (now healed) feet. The hospital drama had been a brutal teacher; its lessons were not theatrical justice but the reassembly of a life into a steady, honest architecture. I slept that night with quiet confidence, certain that I would wake to a morning in which I belonged to myself and to the people who truly wanted to be with me for what I offered, not for what I could do on command.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

Parents Said My Headaches Were ‘Attention Seeking ‘ The Brain Scan Showed What They’d Hidden. CH2

Parents Said My Headaches Were “Attention Seeking.” The Brain Scan Showed What They’d Hidden PART 1 The migraines started…

My Dad Slapped Me For ‘Disrespecting’ His New Wife The Hidden Camera Changed Everything. CH2

My Dad Slapped Me For ‘Disrespecting’ His New Wife The Hidden Camera Changed Everything Part One The slap arrived with…

My Stepdad Dragged Me Out of Bed By My Hair While Mom Filmed Him Laughing. CH2

My Stepdad Dragged Me Out of Bed By My Hair While Mom Filmed Him Laughing Part One Stop. Stop, stop—you’re…

My Mother Banned Me From Family Gatherings So My Pregnant Sister Wouldn’t Feel Jealous of My Career. CH2

My Mother Banned Me From Family Gatherings So My Pregnant Sister Wouldn’t Feel Jealous of My Career Part One They…

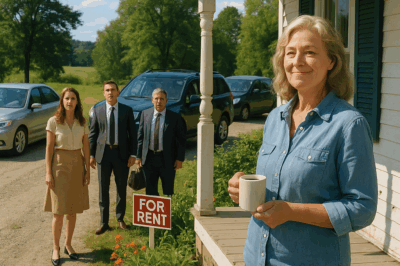

I had just bought the country house when my daughter called: “Mom, get ready! In an hour… CH2

I had just bought the country house when my daughter called: “Mom, get ready! In an hour, I’ll be there…

MY BROTHER BROKE MY RIBS. MOM WHISPERED, “STAY QUIET -HE HAS A FUTURE.” BUT MY DOCTOR DIDN’T… CH2

My brother broke my ribs. Mom whispered, “Stay quiet – he has a future.” But my doctor didn’t blink. She…

End of content

No more pages to load