HOA President Tried to Stop CPR… She Never Expected What Happened Next

Part One: Welcome to Sunny Meadows

I never thought I’d be at the center of a neighborhood scandal, but life loves its little plot twists. My name is Michael, and I’ve been a paramedic for twelve years. Twelve years is long enough to know the difference between noise and signal, between panic and crisis, between posturing and the truth. It’s long enough to forget how to be shocked—and yet, somehow, I still found a way.

I moved into Sunny Meadows six months ago, thinking I wanted peace. The community brochure showed lemony sunlight spilling over sidewalks, dogs with glossy coats tugging children down manicured streets, trees pruned like elegant cursive. It looked like a place that held its breath at twilight and exhaled safety.

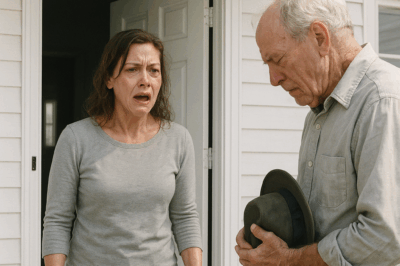

On day one, I rolled my single box of pots and pans and my first-aid kit up the driveway. I was still peeling blue tape off a cardboard wardrobe when she appeared. Clipboard in hand, posture carved from marble, a smile sharpened into a blade—it was the first time I met Karen Wilkins, the president of the Sunny Meadows HOA.

She didn’t say hello. She didn’t say welcome. She read, as if from a script. “Garbage bins must be brought in by 7:00 p.m. Any exterior modification, including a new mailbox, requires written approval. Front doors must be in one of the approved neutral palettes. Preferred codes are Serenade Sand, Whisper Oat, and Biscuit Beige.”

Her tone had the flat sheen of a hospital wall. I’ve told a husband his wife didn’t make it. I’ve explained to a mother that compressions sometimes break ribs. I know how authority sounds when it’s necessary. This was different. It was theater. It was the confident pull of someone who’d learned that control can be mistaken for care.

I thought: she’s overenthusiastic. I thought: this is fine. I was wrong twice in ten seconds, which has to be some kind of record.

Part Two: Rules Are Rules

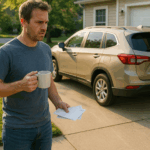

Three weeks in, I got my first violation notice: a photograph of my driveway at two in the morning, empty, because I was on an overnight shift. “Neighborhood occupancy appearance concerns,” the note read, signed by Karen with a cheerful smiley face that looked like a wink aimed at a firing squad.

I shrugged it off. Then came the second notice: my lawn had grown half an inch too tall while I was working a seventy-two-hour emergency response rotation after a pileup on the interstate. I didn’t argue; I hired a lawn service. I asked my neighbor, James, to shove my bins back from curb to garage while I was gone. I painted my front door Biscuit Beige. The color looked like someone had distilled boredom into latex, but I did it anyway.

I attended the next HOA meeting, hopeful, arms open. “I’m a paramedic,” I said. “Sometimes I’m gone for days. Could there be flexibility?”

The room went still. Karen adjusted her designer glasses and sighed with theatrical weight. “Rules are rules,” she said, and I swear she said it like the rules had feelings. “If we make exceptions for you, everyone will want special treatment. Perhaps this neighborhood isn’t the right fit for someone with your lifestyle.”

Lifestyle. The way she said it made saving lives sound like a bad habit I should try to quit.

I kept my mouth shut. In paramedic school, they teach you to pick your moments. You can’t argue with a heart that’s stopped. You can only work. So I worked—on my lawn, on my bins, on my door, on my silence. I let the small things pass.

Part Three: The Scream

Sunny Meadows loved Saturdays. Morning walkers made polite loops, white sneakers kissing the pavement. Sprinklers waltzed across trimmed grass. Children’s laughter stacked in the air like sugar cubes.

On one particular Saturday, the sun poured down like honey. I was off-duty for once, a glass of iced tea sweating on the patio table, a dog-eared mystery novel in my hands. On the other side of the fence lived the Johnsons—Earl and Margaret—an elderly couple who spent afternoons doing crosswords in the shade, pewter hair lit by the late light.

I heard the sound first as a tremor in the air, a disturbance that found the bones in my ears. Then the scream. It split the afternoon cleanly in two. The book dropped. I vaulted the fence. The world narrowed to a corridor of purpose.

Mr. Johnson lay sprawled on the patio stones, blue creeping into the borders of his lips, eyes unfocused, chest still. There are seconds in any crash when the mind refuses to accept that gravity has changed. I didn’t give mine the chance.

“Call 911,” I told Margaret. My hands found their rhythm. Heel of the palm. Depth, recoil, count. 1, 2, 3, 4. Breathe. The numbers in my head became drumbeats that kept fear at bay. Training is a rope thrown into a flood. I clung to it.

Part Four: The Interruption

I didn’t hear the gate. I didn’t hear the footsteps. I heard a voice I knew all too well, trimmed to a scalpel edge.

“Excuse me. What exactly do you think you’re doing?”

I didn’t look up. “Performing CPR.” My arms were pistons. “Step back.”

“This is a violation of section five, paragraph three of our bylaws,” she declared. “No medical procedures in public view. It disturbs the community atmosphere.”

I stared at the pale shell of Mr. Johnson’s face, then at Karen’s shadow stitching itself across his shirt. For a heartbeat, disbelief stopped my hands. Then disbelief moved aside, and I got back to work. 1, 2, 3, 4.

“He’s dying,” I said.

Unfazed, she lifted her phone. The camera lens was a cold eye. “I’m documenting this violation. As HOA president, I order you to stop immediately or face fines.”

I didn’t stop. I fell into the tunnel where only the next compression exists. In the tunnel, Karen was just a noise, smaller than a siren, smaller than a heartbeat on a monitor coming back as a delicate green mountain range.

“Touch me again while I’m performing emergency medical care,” I said through my teeth when she grabbed for my shoulder, “and I’ll have you charged with obstruction.”

Most people would back down. Karen doubled down.

She turned and barked into her phone. “We have an unauthorized person performing prohibited activities in the private community. Remove him from the property.”

The words hung in the air like they could alter oxygen into something else.

Part Five: Stand-Off on the Stones

The guards arrived fast, black polo shirts, radios hissing on their shoulders. They hesitated, confronted with a tableau that no training manual prepares you for: a man pressing life into a neighbor’s chest while the HOA president hovered like a thundercloud.

“Ma’am,” one guard said carefully, “he’s clearly giving medical aid.”

“I don’t care,” Karen snapped. “He’s not authorized. Remove him.”

The guard’s fingers reached toward my arm. Sirens braided themselves into the distance, gaining volume until they folded themselves into the yard. The ambulance nose eased to a stop at the curb.

My team spilled out: Dave, my supervisor, big and fierce and tender when it mattered; Luna, precise with an IV like she was threading a needle in the dark. They saw the scene in a single swallow.

“What the hell is going on?” Dave asked.

“This man is in cardiac arrest,” I said, compressions pounding, voice steady. “She tried to stop me.”

Dave slid into position in a seamless exchange, hands taking over compressions, shoulders stacked, rhythm perfect. Luna knelt at Earl’s side, already priming the line, the defibrillator pads whispering as adhesive met skin.

“Clear,” she said, and the machine voiced its cool warning. The guards stepped back, their faces undone by a new understanding that rules lived under larger laws: gravity, time, and the desire to keep a stranger breathing.

Karen wasn’t finished. “I want him arrested,” she shrieked, pointing at me. “He violated multiple HOA regulations.”

Dave turned to her, and his gaze could have bent steel. “Ma’am, step back or you’ll be explaining this to a real officer in about thirty seconds.” His voice contained the gathered authority of a thousand shifts. Even Karen shut up.

Within minutes, a pulse trembled back under Luna’s fingertips. The defibrillator sighed into baseline, the monitor sang the shy return of a rhythm. They loaded Mr. Johnson into the ambulance. He wasn’t out of the woods, but the path existed again.

As the doors closed, I turned to Karen. The yard smelled like adrenaline and azaleas.

“You interfered with emergency medical treatment,” I said. “You tried to pull me away. That’s a crime.”

For the first time, fear flickered in her eyes.

“Our bylaws,” she began.

“Do not override state law,” I finished. “I hope you recorded everything. It’ll be great evidence.”

Part Six: The Long Night

After the ambulance left, the neighborhood gathered in uncertain clusters, like minnows when the shadow of a large fish passes overhead. I answered a detective’s questions, factual, calm. Margaret held my hand as if it were the last intact thing in a shattered room. The sun sank and took the yard’s warmth with it. The guards disappeared, their radio chatter suddenly small.

At home, my Biscuit Beige door looked ridiculous, like a joke I’d told about myself. I showered until the steam cleared my lungs and then paced the living room until pacing felt like tap-dancing on eggshells. Sleep arrived in broken glass. Every time I closed my eyes I saw Karen’s phone lens staring back, cool and certain.

In the morning, I brewed coffee and found the neighborhood group thread detonated overnight. People who’d never made a peep were now typing manifestos. There were words like “unbelievable” and “I always said” and “I thought it was just me” and “my teenager got a violation for chalk drawings.” Screenshots multiplied. Someone had clipped a frame from Karen’s video and circled her hand on my shoulder. Someone else had quoted state statutes I’d read for work but never imagined would be part of my home life.

The detective called. “We’ll need your statement on record,” she said. “Also, the video is… illuminating.”

“How’s Mr. Johnson?”

“Holding,” she said. “It helped that treatment started immediately.” Her voice warmed. “You did the right thing.”

I hung up and stood in my quiet kitchen, the fizzing energy of the night turning into focus. I thought of Karen’s tight smile on my first day, her sigh at the meeting, her phone lifted like a speculum that could examine and diagnose the whole block. I thought of Mr. Johnson’s chest under my hands and the first tickle of a pulse returning like a violin tuning itself in the dark.

Part Seven: Paper Shields

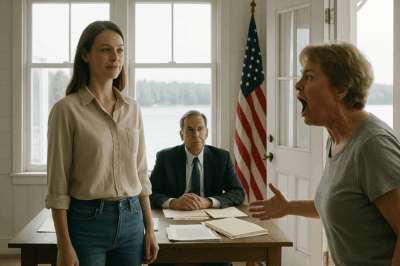

The HOA called an emergency meeting. Rooms like that are designed to feel civil—folding chairs, a pitcher of water sweating on a table, a checkered agenda. But civility is set dressing if the people inside refuse it.

Karen arrived first, flanked by two allies who had mastered the art of nodding at the right times. She wore a navy sheath dress and a necklace that looked like a chain of tiny armor plates. The clipboard was gone; in its place, a stack of printed bylaws bristling with fluorescent tabs. A lawyer sat two chairs down from her, expression neutral the way a blade laid flat looks harmless.

Neighbors trickled in. James took a seat beside me, jaw clenched. A young woman I’d only seen jogging—Sierra, I learned—paced like a tethered storm cloud. Margaret came in last, wearing a cardigan the color of a robin’s egg. She folded herself into a chair and fixed her gaze on the table as if her eyes were weighted.

The room hushed. Karen stood.

“We are here,” she said, “to discuss an incident that occurred yesterday involving a violation of section five, paragraph three—”

“Sit down,” Margaret said. The voice that had trembled on the patio was gone. In its place was a tone I recognized: the one that makes people stop moving stretchers and listen.

Karen blinked, stalled for an instant. “Mrs. Johnson, with all due respect—”

“You showed none yesterday,” Margaret said. Her hands shook, but her words did not. “You interrupted the man who kept my husband alive. You ordered people to remove him. You waved papers while he did chest compressions. Our lives are not your stage.”

Murmurs rolled the length of the room. Karen’s lawyer touched her sleeve, a subtle anchor. He stood and cleared his throat.

“Let’s proceed with care,” he said smoothly. “There are procedures for addressing… misunderstandings.”

“It wasn’t a misunderstanding,” James said. “We all saw the video.”

Sierra planted her palms on the table. “I have two kids who ride their scooters in the cul-de-sac. You sent a violation notice because the chalk lines were ‘visual clutter.’ You said the sound of their wheels ‘disturbed the community aesthetic.’ Now you want to talk about procedures?” She laughed, a sound without humor. “The only procedure that mattered yesterday was the one keeping a man alive.”

The lawyer glanced at Karen, then back at us. “I understand emotions are high.” He folded his hands, the universal sign for control. “But a homeowners’ association has the authority to enforce rules that maintain property values and quality of life.”

“Quality of life,” Margaret repeated, tasting the phrase like something spoiled.

I stood. I don’t like the sound my voice makes when I’m angry. It gets soft. The softness is the cool side of a flame.

“I’m not here for a fight,” I said. “I’m here because I live here. Yesterday, I did the work I’m trained to do. Your president tried to stop me, physically, while my neighbor’s heart had stopped. The law is clear. If you think a paper shield protects you from common sense, you have mistaken paper for steel.”

Karen spoke then, sharp and bright. “You were performing a medical procedure in public view. That is against our bylaws.” She tapped a tab in her stack. It sounded like a tiny gavel. “Chaos cannot be permitted to erode our standards.”

“Chaos?” Margaret asked, her voice ripping. “You call my husband dying chaos? You call saving him chaos?”

Karen’s face flickered. The mask slipped, then slid back into place. “I am committed to fairness,” she said. “If we allow exceptions—”

“Exceptions?” Sierra’s knuckles went white. “You fined my grandmother for a wind chime. A wind chime, Karen. You don’t know what fairness means.”

The board’s lawyer finally spoke from the far end of the table. He had the look of a man who’d been backstage too long and realized the script wouldn’t hold.

“I’ve reviewed the video,” he said. “There is potential criminal exposure for obstruction of emergency services. There also may be civil exposure for the HOA depending on whether the president was acting within the scope of her duties.”

Karen went very still. “You work for us,” she said, the words curdled with surprise.

“I work for the association,” he replied. “The members.”

The room tilted in the way only a room full of adults can tilt: quietly, with the friction of people rearranging their positions on a chessboard.

Part Eight: The Knock

The detectives returned two days later. They didn’t pound. They knocked the way people knock when they’re sure the door will open. I let them in. We sat at my kitchen table, which was still littered with the clumsy remains of last night’s attempt at cooking something that wasn’t reheated.

They asked for a formal statement. I gave one, simple and complete. Dates. Times. Words. Hands. The way Karen’s fingers had tightened on my shoulder. The way her voice had sliced the air. The way the guards had reached for me and then stopped when the ambulance arrived as if a spell had broken.

“We’ve also obtained the original file from Ms. Wilkins’ phone,” the detective said. “She’s surrendered it.”

I could almost see the moment: Karen, sitting at her own kitchen table, the clipboard pushed away, the phone sheathed in stillness for once. Looking at the device that had always been a weapon and knowing it had become the opposite.

“We’ll keep you updated,” the detective added. “Also, Mr. Johnson is awake. He asked about you.”

“Can I visit?”

“Mrs. Johnson said yes.”

The hospital’s cardiac unit has a smell people don’t talk about. Not the antiseptic; that’s obvious. It’s the layered scent of paper flowers left by grandchildren, of coffee cooling in a volunteer’s mug, of fear thinned out enough that you can walk through it like mist.

Mr. Johnson’s color had returned to the neighborhood of normal. He looked smaller in the bed. Recovery shrinks people for a while; they grow back into themselves when they’re ready. Margaret sat by his side, her hands smoothed into careful stillness. When she saw me, she rose and hugged me with a strength that startled us both.

“You came,” Earl said, his voice two sizes too small.

“We don’t leave our own,” I said.

He tried to smile. “Those bylaws,” he whispered, sharing a joke he couldn’t yet laugh at.

We talked for a few minutes about weather and crossword clues and dogs who know the sound of the treat bag. When I left, Margaret pressed a folded paper into my hand. In a looped, steady script, she’d written, Thank you for giving me my husband back.

Part Nine: The Charges

News travels differently when you live in a place like Sunny Meadows. It doesn’t sprint or leap. It moves like water through root systems, slow and inevitable. One morning, it reached every kitchen and mailbox at the same time: the county had charged Karen Wilkins with obstruction of emergency services, attempted assault, and filing a false report.

There was silence first. Then the sound the neighborhood made was strange: not cheering, not mourning, but a recalibration. The next HOA meeting was jammed with faces I’d never seen in that room. People who had kept their heads down. People who had paid their fines and trimmed their hedges and swallowed their anger like a pill that didn’t dissolve. They came to watch how this would go.

Karen arrived with a different kind of poise, brittle and bright. She sat without speaking. When the board attorney announced that the HOA’s insurance would not cover acts that might be criminal, a low gasp traveled like a ripple across the folding chairs.

“If a civil claim is filed and the court determines that Ms. Wilkins acted outside the scope of her duties, the association could be liable,” he said. “However—”

He didn’t need to finish. The room understood all at once: “the association” meant the members. It meant everyone. It meant the fines that funded the seasonal wreath budget might become a dam against a flood they had neither caused nor wanted.

The vote to remove Karen was unanimous. Even her allies—if allies they were—bowed their heads in a choreography of sudden distance. There’s a way a room feels when a crown is taken off. It’s lighter. It’s also a little embarrassed, like everyone has realized they laughed at the wrong parts of a joke.

Part Ten: The Lawsuit

A week later, the Johnsons filed their civil suit. The number sat on the page like a brick through a window: five million dollars. People asked each other at the mailbox what five million looked like in the real world. How many driveways. How many front doors painted the approved tones. How many polite nods would be required to fix that kind of mess.

News vans came once, then twice, then never left. They parked at the end of the cul-de-sac while local reporters practiced concerned faces. I kept my head down and went to work each morning. My colleagues teased me at the station, the way medics do when they don’t know how to say something like I’m proud of you without sounding sentimental. Dave clapped my shoulder once and left his hand there for a beat too long.

Karen avoided me. I would see her in the distance, her figure drawing a hard outline against the soft street. Once, I passed near enough to hear her say to someone on the phone, “I did what was necessary,” and I wondered whether she truly believed that or if she needed to say it out loud to keep from sinking.

Part Eleven: Court

Courtrooms are different from television. The wood is the same; the gravity is real. Rules hang there too, but not the kind you can color-code with tabs. There are rules that decided whether a person walks out the same door they walked in.

I sat at the back during the preliminary hearing, unremarkable in a jacket one degree stiffer than my comfort zone. The prosecutor moved with the calm of someone who’s already placed their chess pieces exactly where they want them. Karen’s lawyer countermoved with elegance and urgency, but the video welded itself to the facts like a tight seam.

They played it in a hushed room: Karen’s phone capturing my hands moving, my voice warning, hers ordering, the guard’s hesitation, the ambulance’s arrival, the glare Dave had leveled that had stilled the air. The sound was tinny, a little distorted, but the essential was clear.

The judge’s face didn’t change while it played. When it ended, he shuffled papers and looked up with the kind of tired kindness I’ve seen in the eyes of old surgeons. He set the next hearing date and denied a motion to dismiss the obstruction charge. Karen closed her eyes for a heartbeat and then opened them again, and for that, I felt a sliver of something like pity. Not forgiveness, not warmth, just the recognition that gravity is impartial.

Outside, a reporter with eyes like camera lenses asked if I had a statement. I shook my head. The only statement I wanted had been delivered to Mr. Johnson’s chest on a Saturday afternoon.

Part Twelve: The Reckoning at Home

When you take down a scaffold, you see what it was holding up. Without Karen’s weekly notices and sudden rule interpretations, Sunny Meadows discovered a cautiously relaxed posture. People edged their lawn chairs two inches closer to the sidewalk. Kids chalked galaxies on the cul-de-sac. Sierra rigged a little free library with her daughters, and nobody reported it for violating line-of-sight requirements.

At the next HOA meeting, the board replaced panic with prudence. The lawyer explained, in phrases chosen with tweezers, the contours of the HOA’s potential liability. They opened the floor not for complaints, but for ideas. James suggested a “community response liaison,” a volunteer who would be the point of contact when emergencies made rules feel small. I suggested CPR classes at the clubhouse with a discount for residents. The board agreed. Luna offered to help teach on her days off, and I watched a handful of neighbors exhale in visible relief, as if the word “compressions” had finally been attached to something other than chaos.

Margaret stood and read a statement. Her words traveled like a slow bell. “We moved here to be near our grandchildren,” she said. “We love the flowers and the sidewalks. We love the quiet. But quiet is not the same as safety. Safety is what happens when people act like neighbors.”

The room stood and clapped, and not the perfunctory kind of clapping you do when you know the meeting can’t adjourn until you’re polite. It was clapping that sounded like a heart starting again.

Part Thirteen: What Five Million Means

The Johnsons’ attorney, a woman with a gray streak like lightning in her hair, sat with them on their porch as they answered questions from the homeowners who dared to ask. People whispered the number as if speaking it too loudly would make it larger.

“It’s not about ruin,” Margaret told them. “It’s about responsibility. We’re not angry at our neighbors. We’re angry at what was permitted to grow here under the name of order. We’re angry at what nearly cost me my husband.”

The attorney clarified gently that the suit named both Karen and the association, that the court would decide what portion of responsibility lay where. She said words like negligence and damages and punitive, each landing with soft weight.

After the crowd thinned, I sat with the Johnsons and the attorney on their porch steps. Earl had regained some of his volume and humor. He poked the air with a finger. “You know, kid, you keep this up and you’ll be president.”

I laughed, a quick bark that turned into a cough of surprise. “I don’t even like Biscuit Beige,” I said.

“Then maybe that’s exactly why,” Margaret said, smiling small but real.

Part Fourteen: Cracks in the Mirror

The worst part about people like Karen is that they believe they’re doing good. That belief is armor that can’t be pierced by logic, only by loss. After the charges, she disappeared from the sidewalks. Her front yard stayed perfect, a green plane with no story. Lights went on and off at the usual times. Packages arrived and were brought inside. But she was a ghost in a house that didn’t know it had one.

One evening, I saw her at the mailbox cluster. It was nearly dusk, the hour when the neighborhood slips into silhouette. She stood with a letter in her hand, reading and rereading it as if the words would change if she stared hard enough.

She looked up and saw me. For a second, we were two people waiting for the same light to change. Then her chin lifted.

“I hope you’re satisfied,” she said. It was almost a whisper, but the old steel threaded through it.

“Satisfied?” I asked. “A man is alive. That’s the only part that satisfies me.”

“You humiliated me,” she said. “You turned them against me.”

“You did that yourself,” I said, softer than I intended. “You could have chosen to help.”

She laughed once, a brittle sound. “Help? I kept order here. For years. Nobody complained.”

“They did,” I said. “Just not to you.”

For a heartbeat, I thought she would throw the letter at me, or the mailbox, or the sky. Instead, she pressed her lips together and walked away. I watched her go and thought that there are two kinds of power: the kind that opens gates, and the kind that counts the height of the grass on the other side.

Part Fifteen: Lessons

The CPR class filled every chair. We borrowed torsos from three fire stations and propped them on tables under the bright clubhouse lights. Dave came, and Luna, and two rookies who watched the neighbors with shy curiosity.

I stood at the front and realized my palms had gone damp in a way they never do on scene. Teaching is a different emergency: it asks you to keep people healthy in the future, not just alive in the moment.

We taught compressions that are deep and fast. We taught how ribs sometimes crack and why that’s okay. We taught how breaths shouldn’t be too forceful, how to let the chest rise like a tide and fall like one too. We taught how to use an AED—the little machine with big courage.

We taught something else too, though we didn’t write it on the slides. We taught that life is not an aesthetic. It’s a fact. It’s messy. It’s loud. It’s someone pressing on your chest while your neighbor cries your name. It’s a community forgetting how to be afraid of the things that are good for it.

After class, Sierra’s daughters asked to try the AED pads on a torso. They placed them carefully, giggling over the mannequin’s bland plastic face. “Clear,” one of them whispered with theatrical seriousness, and the room laughed in that way people do when they’ve collectively felt something sharpen into hope.

Part Sixteen: A Visit

On a Sunday soft with weather, I stopped by the Johnsons’ house with a casserole I’d been told by three separate people was “impossible to mess up.” Earl answered the door with a cane he didn’t need yet but felt better carrying. His T-shirt read Best Papa and had a coffee stain like a medal on it.

“We’re going to pretend you didn’t cook that,” he said, grinning. “But we’ll eat it anyway.”

Margaret hugged me and guided me to the couch as if I were a guest of honor and not the paramedic who happened to live next door. We ate. We joked. We watched a video of their grandson’s school play in which he had no lines and stole every scene.

At one point, Earl grew quiet and looked at his hands. “I don’t remember it,” he said. “I don’t remember the patio or the sky. I don’t remember your face above me. But I remember a sound. A beat, like a drum. I think it was you counting.”

“I hope you never have to hear it again,” I said.

He nodded. “Me too.”

Part Seventeen: The Last Meeting

Two months later, the HOA held a meeting that felt like an exhale held too long. The board confirmed that Karen had formally resigned. The new president, a woman named Priya with a voice like steady rain, announced a revision process for the bylaws, with a focus on clarity, compassion, and compliance with actual laws instead of imagined ones.

“We are not a security force,” she said. “We are a community. Our rules should protect our homes and our relationships.”

There were applause, and suggestions, and stories. A man who had never spoken at a meeting told the room about the time Karen measured his holiday lights with a tape measure. A woman confessed she had been afraid to plant tomatoes because they might be visible from the sidewalk. People laughed, and the laughter turned the stories into a way of letting them go.

Priya nodded toward me. “We owe a debt to a neighbor who reminded us that the most important standard is not how things look, but how we care for one another.”

I wanted to disappear into my chair, but Sierra raised her hand and said, “Hear, hear,” and that was that.

Part Eighteen: Sentencing

On the day of sentencing, the courtroom was cooler than August should allow. The judge spoke with grave economy. The obstruction charge, he said, merited a fine, community service hours favoring organizations that provide emergency training, and a term of probation that would hang above future choices like a visible rule no one could interpret away.

Karen stood very straight. When asked if she had anything to say, she said, “I never intended harm,” and I believed her, and I also understood that it didn’t matter. Intention is a lantern that helps us walk in the dark; it does not erase the bruise when you bump into the table.

Outside, reporters pecked for pieces of scandal, and I gave them none. Instead, I went to the station and made sure the AED batteries were charged and then I went home and watered the little ficus that stubbornly refused to die despite the indignity of my schedule.

Part Nineteen: Aftermath

Life did not turn into a montage. It settled. Children chalked. Dogs wagged. The gardener’s truck came every other Wednesday, the orange leaf blower roaming like a small, industrious dragon. The new board sent emails that sounded like letters from a neighbor instead of edicts from a small kingdom.

I saw Karen once more, months later, hauling a paper bag of groceries up her walk. She looked like a woman who had learned that paper bags tear if you pack them wrong. I lifted a hand. She lifted one too, an acknowledgment that we existed on the same street in the same weather, bound by the same imperfect human rules.

Mr. Johnson returned to short walks. He tugged the brim of his cap when he saw me. Margaret began a container garden with tomatoes and basil, and when she set the pots on the front step, a small card from the HOA arrived that read, “Looks lovely. Please share your tomato sauce recipe,” and she cried in the quiet of her kitchen for five minutes before laughing at herself.

Part Twenty: A New Door

On a late afternoon of that milky light fall saves for itself, I stood looking at my Biscuit Beige door. It had become a joke I had outlived. I called Priya to ask whether the new color guidelines had been finalized. “We decided,” she said, “that as long as it isn’t neon and isn’t explicit language, people can make reasonable choices that bring them joy.”

Reasonable choices that bring joy. It felt like a prescription I’d never been brave enough to write for myself.

I painted the door the color of a good cup of coffee. The brush slid. The old beige looked at me and then disappeared under the first coat. James walked by and said, “Finally,” and we laughed the way you laugh when the past isn’t gone but it’s quiet.

Part Twenty-One: The Party

The block decided to risk a potluck. People who had never revealed themselves beyond the mailbox rolled out dishes that told stories: biryani that perfumed the air with cardamom; ribs that gleamed like lacquered mahogany; a suspiciously perfect lasagna from the house with the immaculate hedges; brownies from Sierra’s kids so sweet your teeth sang.

Priya stood on the sidewalk and tapped her glass with a fork. The sound traveled through the gathering hum. “To neighbors,” she said. “To the quiet we keep, and the noise we make when someone needs us.”

Glasses lifted. The sky blushed then settled into evening. A string of lights flickered on across three driveways. A breeze lifted the corners of the paper plates. Someone set music low enough to talk over and high enough to keep a rhythm in the air.

Margaret slipped her arm through mine and said, “You never told us why you became a paramedic.” The question didn’t pry. It offered a chair.

“My mother fainted in a grocery store when I was eleven,” I said. “A woman in a leather jacket knelt by her, took charge, said it would be okay in a way that made it okay. Later, I found out she was an EMT. I wanted to be that sentence in other people’s stories.”

Margaret squeezed. “You are.”

Part Twenty-Two: What Happened Next

People like to button stories. They want the credits to roll with a song they recognize. They want villains punished and heroes thanked and a speech about lessons learned. Real life is less obedient, but sometimes—as if to prove it can—it offers exactly that.

What happened next in Sunny Meadows was not an epiphany but a series of small decisions. The board rewrote the bylaws. They kept the parts that protected us and struck the parts that pretended to. They added provisions that recognized emergencies and carved out a path for judgment and mercy. They created a community emergency plan, a list of residents with medical training or useful skills, a set of phone numbers to call when sirens get lost between doors.

What happened next was that the next time a kid fell off a scooter, three people ran out with ice packs and nobody wondered if bandages were visual clutter. The next time the sprinkler schedule failed and a lawn went brown, the neighbors watered it with their own hoses and not one person took a photo for the purpose of writing a violation.

What happened next was that we remembered we were not hiding from the world behind these sidewalks. We were living here together, and that is both more difficult and more beautiful than any brochure can promise.

Part Twenty-Three: The Ending You Could See Coming

You want to know if Karen went to prison. She did not. She was fined. She did community service in the form of helping set up CPR trainings at three other HOAs, a kind of irony the judge probably appreciated privately. She moved out, eventually. Maybe because the suit settled, or because the mirror in her hallway had begun to show her a shape she didn’t like. Maybe because every time she walked to the mailbox she felt the gravity of what had happened, not as a public disgrace but as a private fact.

You want to know if the Johnsons got five million dollars. They did not. They got enough to pay the medical bills and to fund scholarships for EMTs from our county, named for a man who lived and a community that learned. The HOA paid its portion. There were murmurs. There was tightening of belts. There was, afterward, a steadier kind of spending: on benches for the cul-de-sac, on AEDs in the clubhouse and pool house, on flowers that didn’t need to be measured.

You want to know if I became HOA president. I did not. I was asked. I declined. I prefer the siren’s wail to the gavel’s knock. But I joined the emergency committee, and my number sits on a laminated card in a dozen kitchen junk drawers, which is a kind of honor no plaque can match.

Part Twenty-Four: The Clear Ending

On the anniversary of the day the patio stones tilted the world, I stood at my coffee-colored door and listened to Sunny Meadows breathe. Sprinklers stitched the air. Somewhere, a dog barked. A child shouted a word from a game whose rules I’d never learn. Margaret laughed on her porch and the sound broke into the evening like light.

I thought about that first day, the clipboard, the rules, the door paint, the smiley face that felt like a threat. I thought about the scream and the compressions and the small hands that would place AED pads on a plastic torso because they had learned to do so. I thought about how control masquerades as care and how easy it is to mistake a paper shield for safety.

We keep the things we fight for in a quiet way. Not with speeches, not with banners, but with the ordinary courage it takes to ring the bell next door and ask, “Are you all right?” Sunny Meadows learned that. I learned it again. And in a world that loves its curveballs, that felt like the closest thing to peace.

Mr. Johnson watered the tomatoes that evening, and the spray arced, catching the low sun and fracturing it into a brief, local rainbow. He waved. I waved back. Somewhere, in a room with no windows and a clock that never moves fast enough, a paramedic lifted their hands to a chest and pressed. Somewhere, a rule met a reason and moved aside.

This is how it ended: not with a verdict, not with a headline, but with a neighborhood that finally understood its own heart. Karen Wilkins was officially gone. The bylaws wore new clothes. The door wore a better color. And the next time the world asked us to choose between appearance and life, we chose life before anyone had to say a word.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

My Dad Kicked Me Out Over a Secret, 13 Years Later, He Knocked On My Door and…

My Dad Kicked Me Out Over a Secret, 13 Years Later, He Knocked On My Door and… Part I…

CH2. HOA Karen Busted Into My Lake Cabin — Didn’t Realize I Was Meeting the State Attorney General Inside

HOA Karen Busted Into My Lake Cabin — Didn’t Realize I Was Meeting the State Attorney General Inside Part…

CH2. “May I Take A Turn?—The SEALs Didn’t Expect The Visitor To Smash Their Longstanding Record

May I Take A Turn?—The SEALs Didn’t Expect The Visitor To Smash Their Longstanding Record Part I The sun…

CH2. Three Trainees Confronted Her in The Cafeteria — Moments Later, They Found Out She Was a Navy SEAL

Three Trainees Confronted Her in The Cafeteria — Moments Later, They Found Out She Was a Navy SEAL Part…

CH2. “You Can’t Enter Here!” — They Had No Clue This Woman Would Become Their Military Leader

“You Can’t Enter Here!” — They Had No Clue This Woman Would Become Their Military Leader Part I The…

CH2. “Wait, Who Is She?” — SEAL Commander Freezes When He Sees Her Tattoo At Bootcamp

“Wait, Who Is She?” — SEAL Commander Freezes When He Sees Her Tattoo At Bootcamp Part I — The…

End of content

No more pages to load