HOA Karen Tried to Fine Me for Drinking Coffee in My Front Yard!

Part I: The Violation

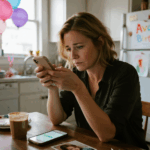

The morning air was crisp, the kind of bright, clean cold that wakes your brain before the caffeine does. I stepped onto my porch barefoot, the boards still cool from night, and wrapped both hands around a steaming mug of coffee. The jasmine along the fence was showing off—white blossoms, green gloss, a smell like memory. For once, the street was quiet. No leaf blowers. No delivery vans. Just the distant scrape of a bicycle kickstand and the soft slap of a newspaper landing somewhere down the block.

I breathed, and for a few seconds it felt like my yard was a room with no ceiling, and I’d finally found the one place in this neighborhood nobody else needed to supervise.

“Excuse me.”

The voice broke the morning like a plate dropped in a kitchen you don’t own. I turned. Karen—our self-appointed HOA storm siren—was already halfway up my walkway, a clipboard hugged to her chest like a life raft. She had on the kind of visor that makes a person look like they never stopped arguing with a lifeguard in 1997 and a pair of sneakers too white to be sincere.

“You can’t do that,” she said.

“Do what?” I asked, not because I didn’t know but because I was still in the part of the day when reality is supposed to make sense.

She thrust the clipboard so close the corner threatened my sternum. On it: a pre-filled violation notice, already signed, the ink still wet. “As per HOA guidelines,” she read, eyes racing ahead of her mouth, “front yards must remain free of unsightly behaviors. Drinking beverages outside is not permitted.”

I looked at my mug. I looked at the morning. I looked at the woman who had once left a note on my door because my hose reel clashed with the concept of serenity.

“It’s coffee,” I said.

She pursed her lips like she could vacuum my soul through her teeth. “Rules are rules. This is your official notice. Repeat offenses will incur fines.”

Across the street, Mr. Jenkins paused mid-hedge-trim and raised one eyebrow. A dog-walking couple slowed to a coast and pretended to tie a shoe. The blinds in three houses lifted and fell like synchronized swimmers. An entire cul-de-sac held its breath for the sound of a fight.

The ridiculousness hit me before the anger did. Then both arrived, argued for a second about who got the wheel, and decided to carpool. I took a deliberate sip and kept my voice steady.

“Then find me,” I said. “But I’m not moving.”

Her nostrils flared. She scratched something on her paper with a flourish that suggested she’d practiced it in the mirror and spun on her heel. “This will not end well,” she informed the street in general, then marched away like a general retreating to plan a second attack.

The door creaked behind me. “What was that?” my spouse, Eli, asked, still blinking sleep out of his eyes. He had one of my old hoodies on and the kind of bed hair that always looked like a good idea.

“Apparently I violated neighborhood harmony,” I said, fanning the paper. “With coffee.”

He stared at the notice like it might sprout legs and flee. “Unsightly behaviors? Did you spill on the azaleas?”

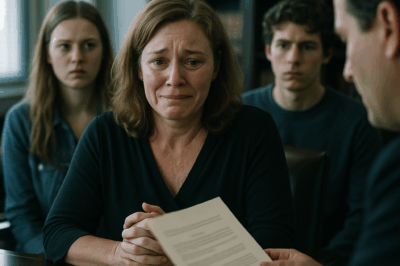

It should’ve been funny. It wasn’t. The paper in my hand felt heavier than it had any right to be, like it was weighted with years of little cuts: the note about our holiday lights being “disruptively whimsical,” the citation when I left the trash bin visible for thirty minutes after pickup, the letter about “unapproved seasonal flags” when I hung a small rainbow on the porch last June. Always phrased like helpful reminders. Always signed with the neat round loops of someone who enjoys their own authority.

By noon, the story had spread faster than the smell of a barbecue. I came back from a grocery run to find the notice on the kitchen counter surrounded by texts from neighbors: Heard she got you. Over coffee?? You okay? Mrs. Alvarez arrived with her terrier, Fideo, and solidarity on her face.

“She cited me last month for a garden gnome,” she said, indignant. “A gnome. Said it was ‘too whimsical for a unified aesthetic.’” She rolled her eyes so hard I worried about her balance. “I told her if uniformity was the goal, she could start by filing a complaint against Mr. Jenkins’s socks. He wears sandals.”

We laughed, because what else do you do when a person confuses control with community? Then we watched Karen’s house at the end of the cul-de-sac and pretended we weren’t.

At four, the doorbell rang and the cavalry arrived. Karen, flanked by two HOA board members in matching polos, marched up the walk in the precise formation of people who believe a clipboard is a personality. She stopped at the edge of the porch as if the boards were lava.

“You were warned,” she said, pointing at my mug. “This is a repeat offense. That’s a $100 fine.”

One of the board members, a sandy-haired man I knew vaguely as Evan (he coached tee-ball and had a habit of apologizing for existing), shifted. “Karen, maybe we should—”

“Rules are rules,” she cut in, slicing him with a look. “We need order, not debate.”

I stood. The adrenaline hit took a lap around my ribcage and settled, buzzing. “Show me where it says coffee is forbidden,” I said. “The bylaws. Show me.”

For a second, something like surprise skittered across her face. She shuffled papers, flipped pages with aggressive efficiency, then tucked the clipboard tighter. She did not produce a single bylaw.

Neighbors were collecting like pigeons at a dropped sandwich. Elbows on fences, arms crossed on driveways, a cluster of kids on bikes pretending they weren’t watching everything. The air felt exactly like the moment a teacher leaves the room and the class decides whether to become feral.

“Until you prove it’s against the rules,” I said—louder now, for the audience—“I’ll drink coffee right here, every morning.”

The murmur the crowd made felt like wind turning. Karen’s cheeks darkened to a shade that looked unsustainable in daylight. She clamped her jaw and marched back down the walkway, trailed by her silent board members, leaving a promise over her shoulder.

“This isn’t over.”

“Good,” I called back. “Neither am I.”

That night, when the house was quiet and the violation notice had migrated to the fridge under a magnet shaped like an eggplant, I lay awake and replayed Karen’s face. It wasn’t coffee. It was control. It wasn’t a rule. It was a habit. And habits only break when you introduce a louder one.

The next morning I poured two mugs, handed one to Eli, and took my seat on the porch like I was clocking in. The blinds down the block lifted in unison, a flock of wary eyes peeking from safe nests. At Karen’s, the curtain twitched. The visor silhouette appeared and vanished. If she was waiting for me to flinch, we were both in for a long day.

By noon I’d decided waiting was a waste of caffeine. The HOA stored its documents at the community center two streets over—an old building that smelled like choir practice and copy toner. A volunteer manned the desk, knitting a scarf long enough to be a moral.

“Hi,” I said. “I’d like to see the bylaws.”

Her needles paused. “Karen didn’t send you, did she?”

“No,” I said. “I sent me.”

She slid a binder across the counter. The spine was cracked, the cover clouded with the fingerprints of a thousand petty grievances. I took it to a table by the window and started reading. Grass height. Paint palettes. Approved mailbox styles (there were four and they were all boring). Nowhere—nowhere—did it say anything about drinking any beverage in your own yard.

After fifteen minutes, someone cleared his throat behind me. I turned. Evan—sandy hair, guilty posture—hovered, looking at the binder like it might scold him. He glanced around, lowered his voice.

“She’s… creative with the rules,” he said, the words like a confession. “Most of us don’t agree with her, but she keeps people scared. She files complaints. Sends letters to employers. She knows how to make hassle.”

“Why does she have that power?” I asked, not rhetorical.

His mouth twisted. “Because no one wants to be the person who makes the neighborhood awkward. So she volunteers, and people let her. Then they forget it’s supposed to be service, not supremacy.”

I closed the binder with a patience I did not feel, took photos of key pages with my phone, and thanked him. On my way home, I rehearsed what I’d say the next time the visor approached. There’s a specific kind of calm you can build when you’ve got the receipts.

When I turned onto our block, she was waiting. Clipboard hugged, posture crisp, face already in the expression that says I dislike you in a way I confuse with morality.

“You again,” she said. “Still breaking the rules.”

I set my coffee on the railing, lifted the binder I’d checked out, and held it up like a Bible in a bad courtroom drama. “Funny thing,” I said. “I read the rules. Every page. Guess what’s not in here?”

For the first time since I’d met her, her smile genuinely faltered.

Part II: The Addendum

By morning, the neighborhood had the charge of a street before a parade—people on porches, garage doors ajar, lawn chairs positioned strategically as if watching me drink coffee were a spectator sport. I hadn’t meant to become a symbol. I just wanted to have breakfast without paying a fine. But symbols have a way of choosing whomever is holding the binder.

Right on cue, Karen arrived with the full board in formation—five members in those HOA polos that try to make volunteerism look militarized. Evan stood near the back, hands in pockets, eyes apologizing to everyone.

“You’ve left me no choice,” Karen declared, projecting her voice like she’d practiced to fill a gym. “Today the board will vote on your violation.”

I stepped down onto the path and met the little semicircle halfway. My heart was tapping a fast beat under my ribs. I could feel Eli’s hand on the back of my leg—a squeeze that said I was not here alone.

“Before you vote,” I said, lifting the binder, “you should know the truth. There is no rule against drinking coffee in your front yard. Not a single one.”

The crowd murmured. The board glanced at each other. Karen’s jaw flexed. She flipped through her clipboard, the papers rattling. “Then you must have overlooked the addendum.”

“Which addendum?” I asked. “Show it to us.”

A ripple of tension crossed the board. One member, a woman with a neat bun and a face like she backed into authority instead of grabbing it, whispered, “Karen, maybe—”

“Here,” Karen snapped, and produced a stapled packet with the triumphant air of a magician yanking a rabbit that had filed for unemployment. “Guideline addendum 47B. ‘Outdoor activities must maintain neighborhood harmony. That includes unsightly behaviors such as loud music, cluttered porches, and yes, beverages in the front yard.’”

Gasps fluttered through the crowd like birds flushed from a hedge. Doubt pricked me—just a pin, quick and sharp. I took the packet and, because I have lived long enough to recognize a forgery, looked at the details. The font was off by a whisper—Times New Roman wearing a disguise. The margins drifted. No header. No footer. No recording stamp from the management company. The signature line had Karen’s handwriting, which had never met a loop it didn’t want to suffocate.

“This isn’t part of the official bylaws,” I said, holding it up so the sun shone through the cheap paper. “It’s a fake.”

The murmurs hardened into words. Mrs. Alvarez stepped forward, her terrier vibrating with secondhand indignation. “She fined me for my garden gnome with that ‘addendum,’” she said. “Said it was ‘whimsical to the point of visual harm.’”

Mr. Jenkins lifted his hedge trimmer like a prop in a play. “She cited me for my wind chimes. Said they disrupted the soundscape.”

A teenager in socks and slides called out from a doorway, “She posted a letter about our graduation banner.”

Evan moved. It was small—a step—but it changed the geometry of the moment. He came to Karen’s side, faced the crowd, cleared his throat.

“We need to talk privately,” he said, to Karen but loud enough for everyone to hear. His voice was unshaking. That seemed to surprise even him.

They withdrew down the sidewalk, the four other board members huddled around Karen like people warming their hands at a fire alarm. The street breathed. The visor was off-balance. We were not.

I sat back down. My coffee had gone cold, but it tasted like victory. Eli leaned against the column and bumped my shoulder with his knee.

“You started a revolution,” he whispered.

“I just wanted to start a morning,” I whispered back.

That evening, our cul-de-sac transformed. It had been months since anyone lingered outside without peering like fugitives. Now folding chairs appeared. Kids drew chalk cities across the asphalt. Someone wheeled out a speaker and risked seventies soul. Mrs. Alvarez brought empanadas that disappeared in minutes. We traded stories and discovered we all had variations on the same one.

“She mailed my boss,” said a nurse named Deena, eyes wide with remembered fury. “Said my trash can was visible and my ‘unpredictable work schedule’ made me a bad neighbor.”

“She made me take down my Cubs flag,” said Mr. Patel, from three doors down, “and I have lived through thirty-seven losing seasons. Thirty-seven. Haven’t I suffered enough?”

“And she told my wife the curtains were the wrong white,” said a man named Mark who always wore a hat. “There are twelve whites, apparently. I did not know that about prison.”

We laughed like people who had been holding their breath and were finally allowed to be ridiculous. Down at Karen’s, the curtains remained shut. The porch light stayed off. You could almost hear the gears grinding.

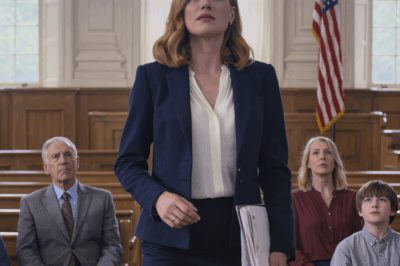

The board called an emergency meeting for the next afternoon. Not at the community center this time. At Mr. Jenkins’s front yard, under a maple that had been shading gossip since the Bush administration. The turnout was biblical. People from streets I’d never walked showed up with camping chairs and folding fans. The energy felt less like a tribunal and more like a potluck where justice was the main dish.

Evan opened the meeting. He didn’t hide behind the polo. He wore a faded Mariners shirt and worry on his face. When he spoke, his voice carried—not loud, just sure.

“We reviewed the addendums Ms. Roebuck”—he finally said Karen’s last name out loud, and it had the effect of saying a spell backward—“has been using to issue citations. They were not approved by the board or the management company. They were never recorded. They are not valid. We are rescinding those violations and associated fines.”

You could feel the tide turn and see the shoreline at the same time. Anger rose—murmurs, then sharper sounds—and then resolve settled over it like a calm on a lake. We were not going back inside.

“Additionally,” Evan said, throat working, “we are moving to remove Ms. Roebuck from her position as chair. Effective immediately.”

They voted. It was swift. It was unanimous. It was the sound a neighborhood makes when it remembers who owns it: not a clipboard, not a visor, not a habit shaped like a person. People clapped. Children who did not understand parliament joined in because clapping is contagious. Someone popped a soda. Fideo barked as if he’d been campaigning for this day his whole life.

Karen did not emerge. The next morning a U-Haul appeared at her curb. The curtains fluttered like someone saying a goodbye you won’t miss. By afternoon, the visor was gone. The clipboard left a rectangle on the hall table where it had lived. The house at the end of the street stood there looking lighter and older, like a bully after the bandages are removed.

Part III: The Aftermath

You expect relief to be instant. It isn’t. It lands in pieces, like a package shipped separately: here’s your porch back, here’s your willingness to wave at a stranger, here’s your willingness to believe a letter in your mailbox isn’t a threat. The first week after the vote, I found myself listening for footsteps on the path that belonged to someone who no longer lived here. I had to teach my shoulders how to drop.

The board met again—this time in the community room with the fluorescent lights and the smell of old coffee we were allowed to drink. We amended the bylaws in public. People argued and then agreed. We added a clause that required any proposed amendment to be posted online and mailed before a vote. Transparency isn’t a cure for mischief; it’s a vaccine.

Evan resigned as treasurer and ran for chair. He won by such a margin even he blushed. In his first official act, he apologized. Not just for letting Karen run wild, but for the years the board behaved like a mirror for one woman’s reflection.

“It should have been service,” he said. “We made it into something else. That’s on us.”

We formed committees that weren’t about surveillance but about services—yard help for seniors, a tool library (Mr. Jenkins donated the first ladder, which felt like a personal growth moment), a monthly swap where people left items on their lawns and they became someone else’s treasures by noon. We created a “porch hour” once a week—seven to eight on Thursdays—where everyone who could sat out front, waved, and, yes, drank whatever they wanted. No fines. No forfeits. Just neighbors making eye contact.

That first Thursday, I fixed a pot of coffee big enough to float a small boat. Mrs. Alvarez arrived with mugs. Deena brought cookies that made me want to believe in God. The nursing student at the corner set up a hammock. Eli installed a string of lights and declared the porch a café and himself a barista. “Our specialty,” he announced to the dozen people who showed, “is a beverage we like to call Lawful Good.”

We laughed, because now we could, and because the joke wasn’t a shield anymore. It was a souvenir.

About a week after the U-Haul, a letter arrived addressed to me in careful, almost cramped handwriting. My stomach did a small, unhelpful dance. I opened it on the porch out of stubborn principle.

Mr. … it began, and scratched out my last name like she’d weaned herself off the formality mid-sentence. Then: “To whom it may concern.” Then a correction: “To you.”

It was from Karen.

She apologized, but not in the way that tries to rewrite a history. She didn’t call it a misunderstanding. She called it what it was: control dressed as care. She wrote about a messy divorce and a job she’d been downsized out of and a house she’d kept spotless because it was the only thing that would obey. She said she had made herself into a person whose only joy was catching people. She said she understood if the neighborhood never wanted to see her again.

I read the letter twice. Eli read it, too, and made a thoughtful hmmm that didn’t land on yes or no. I didn’t feel triumphant. I felt tired and a little sad—the way you feel standing on a beach after a storm, looking at debris and recognizing most of it is just wood that’s lost its shape.

I didn’t write back. Not yet. Forgiveness, I’m learning, is a tool like a hammer. Useful. Dangerous in the wrong hands. Not every job requires it. Some require a level. Some require a tape measure and a plan. Some require you to sit on a porch and drink coffee and not fine yourself for enjoying it.

A month later, Evan stopped by with a folder full of clippings and a grin that didn’t know how to quit. “We’re formalizing the tool library,” he said. “Also—remember when Karen tried to fine you for the rainbow flag? We’re adopting a resolution: flags are allowed. All flags. Except hate.”

He waited, testing the air like a baker testing a loaf. I thought about the June that had made me fold the flag after her letter and tuck it into a drawer that smelled like lavender and fear. I stood and walked inside, opened the drawer, unfolded the fabric, and walked back out.

“Hang it high,” Eli said, and I did. It shivered in the light wind with the kind of energy you only get from objects that mean something.

We called the next porch hour “Mugs Up.” Someone printed flyers—simple black and white—tucked into mailboxes with a cartoon coffee cup on them and the line: Sip what you want. Sit where you like. Let’s be neighbors, not notes.

They came. People I hadn’t met in four years of living here. A teenager with blue hair who showed me her portfolio. A mechanic who taught me the word “idler” and made it make sense. The quiet couple from number 12 who turned out to be competitive cribbage players. Mr. Patel brought chai that made coffee taste like it felt insecure. Mrs. Alvarez produced a second gnome for her front bed, this one holding a sign that read You Are Welcome Here. It was corny. It was perfect.

Karen did not come. She’d moved across town, someone said, into a rental. The story was muddy—hers always had been before she took over the microphone—but the consensus was that she was gone. The visor showed up at Goodwill. The clipboard, hopefully, at the bottom of a box beneath a bowling trophy.

Part IV: The Reckoning

We still had the matter of fines. People were owed money. Some had paid. Some had refused and then been threatened. The board, under Evan, hired a mediator and a lawyer who looked like a friendly wolf. We sent letters—this time written in human English—inviting anyone with a complaint to bring it. The community center smelled like coffee (freely consumed) and nervous hope.

Stories poured out. A single mother who’d paid $200 for having a stroller on her porch “after hours.” A veteran told to remove a flag folding chair because it “cheapened the aesthetic.” A man fined for “aggressive mulching” (I didn’t know what that meant either). We documented everything, rescinded what we could, refunded what we had in the account, set up a payment plan for the rest. We drafted a policy: no board member could act alone again. All violations must cite a specific bylaw, not vibes. Appeals would be simple and fast. We put it all online. Sunshine, as they say, cures certain molds.

A week later, the management company—the one that had happily cashed our dues while ignoring our emails—sent a representative with apologetic hair. He used words like “oversight” and “delegation” and “complexity of community governance.” Evan listened, then handed him a new contract with terms written by our friendly wolf. The rep looked like a man who had been invited to a small, polite war and realized he was the only one without a helmet.

At the end of the meeting, the nurse, Deena, raised her hand. “Can we talk about lawns?” she asked. A ripple of groans and laughs. She smiled. “Not to fight. To fix.” We set a greener standard—less water, more native plants. It was small, and it mattered, and it felt like the opposite of what we’d been doing: making rules to make life better instead of making life smaller to fit rules.

I still thought about the forgery. I couldn’t shake the image of Karen at a printer, changing a font, adjusting margins, stapling lies to truth. I told myself the letter was enough. Then I saw Mrs. Alvarez smoothing a bill refund check that would go to her granddaughter’s quinceañera dress and Mr. Jenkins hanging wind chimes with careful hands, and my anger settled into a shape I could carry without it burning me from the inside.

On a Tuesday morning, when the light was good and the jasmine was loud, I wrote to Karen. I told her she’d hurt people. I told her she’d be welcome back to the neighborhood as a neighbor, not a monitor, if she ever wanted to try being different. I told her there were porch lights on for her if she came without the clipboard. I put a stamp on the envelope and walked it to the box with a sense of closure I didn’t realize my body had been waiting for. Forgiveness, the hammer, used to drive one sturdy nail.

She didn’t write back. That was okay. Sometimes you finish a conversation with yourself, not with the person who started it.

Part V: The Ending We Chose

Months later, on a morning a lot like the one that started all this, I stood on my porch with a cup of coffee and watched the neighborhood move like it had always meant to. Kids on bikes, shoelaces slapping. Mr. Patel’s wife and Deena arguing lovingly about cilantro. A paper boy launching the news in arcs that spoke of competence and boredom. Eli sat on the steps beside me in his hoodie, hair stubborn as ever, mug pressed to his lip like an idea he hadn’t committed to yet.

“You’re thinking,” he said.

“Always a mistake,” I said, and he nudged me with his knee.

We’d chosen our ending long before we knew we had the right to write it. We had chosen it when we decided to sit outside and not start a fight but not leave either. We’d chosen it when we checked out the binder instead of waiting for a knock. We’d chosen it when we turned a cul-de-sac into a circle again.

Our flag snapped softly. The gnome held its sign like a protester who knows the work is never done. Across the street, Evan waved from a yard where a ladder leaned and did not threaten to fall. He looked relaxed in the way of men who have taken responsibility and not died from it. Behind him, the tool library shed—painted a cheery blue approved by the bylaws—stood open. A kid returned a rake taller than he was. He handed it over like treasure. It was.

On the first anniversary of The Coffee, we made it a holiday. No official name; just a Saturday morning we agreed to start at nine instead of ten. People brought mugs and folding chairs and exactly one banjo. We held a micro-parade—kids on scooters, Deena in a party hat, Mr. Jenkins driving his lawn tractor slow enough not to dump the passenger, Fideo in a bandana that read CITIZEN. At the end, we stopped in front of my porch because that’s how geography works, and I climbed two steps and cleared my throat like I was about to say something profound and then thought better of it.

“To coffee,” Mrs. Alvarez said, lifting her mug.

“To neighbors,” Mr. Patel added.

“To bylaws that can survive sunlight,” Evan said.

“To being left alone unless you need help,” Eli said.

We drank. We breathed. The sound of mugs setting down, the small clinks, was the sound of a neighborhood putting itself away after joy—not because joy wasn’t allowed, but because it was normal now. Which is the better victory.

Karen didn’t show. But a month later a postcard arrived. It was of a beach somewhere generic. The handwriting was the same careful, anxious script.

I hope you’re well, it read. I drink my coffee outside now.

That was enough. More than enough.

That night, when the sky went the color of sanity and the jasmine retold its one good story, I sat on my porch with a mug that no longer felt like a weapon and watched my yard be a yard. The boards were warm from the day. The house breathed. The neighborhood did too. I raised my cup not in defiance, not in victory, but in something steadier—the ordinary gratitude of a person allowed to exist on his own porch without permission.

The battle was over a long time ago. What remained was the life. And it tasted, at last, like coffee.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

After My Husband’s Death, My Stepchildren Wanted Everything—Until My Lawyer Revealed The Real Will

After My Husband’s Death, My Stepchildren Wanted Everything—Until My Lawyer Revealed The Real Will Part One I never thought I’d…

When My Husband Called Me “Just A Burden” After My Surgery—I Changed Our Estate Plan That Night

When My Husband Called Me “Just A Burden” After My Surgery—I Changed Our Estate Plan That Night Part One…

Husband’s Pregnant Mistress And My Sister Showed Up At My Birthday—Then I Made An Announcement

Husband’s Pregnant Mistress And My Sister Showed Up At My Birthday—Then I Made An Announcement Part One I never…

My mom slapped me at my engagement for refusing to give my sister my $60,000 wedding fund, but then…

My mom slapped me at my engagement for refusing to give my sister my $60,000 wedding fund, but then… …

Too Ugly for My Sister’s Wedding, So I Became a Lingerie Model Instead

Too Ugly for My Sister’s Wedding, So I Became a Lingerie Model Instead Part I — The Test Shot…

My Family Mocked My Law Degree, Until They Discovered I Won The Case That Changed Everything

My Family Mocked My Law Degree, Until They Discovered I Won The Case That Changed Everything Part 1: The…

End of content

No more pages to load