HOA Karen Called 911 After I Slept at My Cabin—Then Froze When She Learned Who I Am

Part I: Blue and Red on Pine

The blue and red lights washed over the knotty pine like a tide, turning my porch into an aquarium of color. I stood there in flannel pants and a T-shirt that had seen better mornings, coffee steaming in my hand, trying to memorize how surreal everything looked: the lake behind the trees, still and black as polished stone; the frost threading the grass by the steps; the woman in a beige pantsuit standing with her arms crossed like she owned the sky.

“That’s him, officers—the trespasser,” she declared, chin high. “He broke in last night. This property has been vacant for months. There’s no way he belongs here.”

She had one of those highlighted bob haircuts that nods along with a person’s certainty. The clipboard tucked under her arm looked battle-scarred, as if it had been used to swat not just rulebreakers but entire summers. She radiated middle management: the power of a gavel, the soul of a parking citation.

The lead officer—tall, graying at the temples, with the calm posture of a man who had learned to hear stories before he believed them—took in the scene and addressed me first. “Sir, we got a call about a burglary in progress. Can you provide identification?”

“Of course.” I handed over my driver’s license and, without commentary, the second card I keep behind it: the one with my name, seal, and title. Daniel Morrison, Senior Compliance Officer, State Real Estate Commission.

His partner swept a flashlight across the frame, pausing at the lock that hadn’t been tampered with, the windows that hadn’t been forced. The lead officer checked my license, then the second card, then me, then—slowly—the woman.

“Ma’am,” he asked, voice changing shape, “do you know who this is?”

“I don’t care who he claims to be,” she snapped. “He’s trespassing on HOA property without authorization. I am the HOA president of Pine Ridge Estates, and I know every single homeowner in this community.”

“Ma’am,” the officer said gently, “this is Mr. Morrison. He’s the senior compliance officer for the State Real Estate Commission.”

The color went out of her face in a single smooth pour, like a bathtub yanked of its plug.

Three days earlier, I’d been in my city office, elbow-deep in a case file about an HOA that had reinvented fines as a self-funding hobby, when my mother called to say Uncle Robert was gone. He’d been more than my uncle. When my father left, Robert took me to county fair demolition derbies and taught me to sharpen a pocketknife and put a canoe in the water without showing off. He let me name the cabin’s first canoe after the dog that had rescued me from middle school. He never wore a watch, and yet he was never late.

“He left you something,” my mother said, the grief and the surprise stitched together. “The cabin.”

The attorney mailed the deed and a set of tarnished keys. He wrote that taxes were current, the transfer completed, the title clean. I drove up two days later—not to investigate, not to inspect, but to sit with the memory of a man who had taught me that quiet life matters as much as loud success.

The drive took three hours of switchbacks and a longer measure of exhale. I arrived at dusk, with the pines carving the sky into something ancient. The cabin had that same stubborn smile: white paint a little tired at the corners, blue trim that held the light even as it let it go. Inside, the fireplace smelled like old smoke and good winters. I lit a fire, grilled a burger, poured a glass of wine, and fell asleep to the sound of crickets tuning the night.

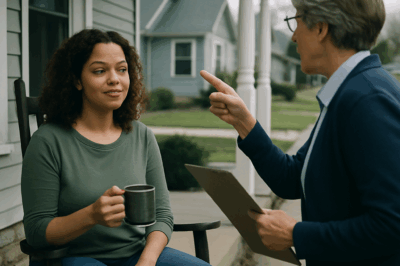

At seven in the morning, pounding rattled the door in a rhythm better suited to warrants. I opened it to find the woman with the clipboard, lips already forming the first of a thousand objections.

“Who are you, and what are you doing on this property?” she demanded.

I was in yesterday’s jeans and the kind of sleep that turns you into a slow-moving target. “Daniel Morrison,” I said. “This is my cabin. I inherited it from my uncle. And you are?”

“Linda Garrison,” she announced, like a brand unveiling. “President of the Pine Ridge Estates Homeowners Association. This cabin has been vacant since Mr. Robert Morrison passed. Occupancy requires HOA approval, payment of transfer fees, and a thorough background check. No one is authorized to be here.”

“I literally own the property,” I said, painlessly. “I have the deed and the keys. I’m spending one night at my cabin, not moving in. I don’t need HOA approval to sleep in my own bed.”

She waved the clipboard as if it had been deputized. “That’s not how it works. Pine Ridge has covenants and bylaws. Did you fill out the application? Pay the $500 transfer fee? Have you read the new resident orientation packet?”

“Linda,” I said, “I appreciate your dedication. Truly. I also need coffee. If you’ll excuse me—”

She jammed her foot against the door, the face of control trying on righteousness. “If I see you here tonight,” she warned, “I will call the police.”

She made good on the promise. The officers did the rest.

“Mr. Morrison,” the lead officer said now, handing back my ID, “we won’t need to see the deed tonight, but I appreciate your offer. My captain attended your seminar on property law last spring.”

He turned to Linda. “Ma’am, are you aware that filing a false police report is a crime?”

“I didn’t file a false report,” she said, but it came out like a question. “He’s not authorized by the HOA. He’s not—”

“He owns the property,” the officer said, carefully patient. “HOA disputes are civil matters. Trespass is criminal. You can’t trespass on your own deed.”

Linda’s expression ran the spectrum—red indignation, pink embarrassment, an ashy white that looked like the aftermath of a lightning strike. The clipboard hung loose in her hand.

“Officers,” I said, “thank you for your time. I’d like to file a formal complaint. I was awakened from sleep in my own cabin by police responding to a false report of burglary. Ms. Garrison has harassed me about my lawful presence, and she threatened to call you if I remained.”

The second officer nodded and flipped open his notebook. “Would you like to press charges for the false report?”

Linda’s mouth opened and then forgot what it meant to move. She looked suddenly smaller, like the world had bent wrong.

“You can’t be serious,” she whispered. “I was protecting the community.”

“From its lawful property owners?” I asked, not unkind.

The night reached back for its quiet. The officers took statements. Linda called a husband, a lawyer, two board members. Everyone on the other end of her calls seemed to know what she didn’t: that morning had started a movie and the ending had already been filmed.

Part II: The Cabin, the Rules, and the Line in the Trees

By the time the sheriff’s suv taillights disappeared, the sky was more cobalt than black. The lake had a skin of mist, the kind that makes sound think twice. Linda lingered in my driveway with that clipboard like it had a line to God.

“You’re not really going to file a complaint,” she said, words brittle. “I was just doing my job.”

“Your job,” I said, “is to manage legitimate HOA business—not to invent rules, not to weaponize 911, not to turn property rights into a performance. Review your bylaws. You’ll be hearing from me.”

Her eyes flicked to the edge of the porch where, years ago, Uncle Robert had carved a tiny mark in the wood for every fish he never caught. I went inside and closed the door gently. Anger would have been easy. What I felt was clarity, washed and dried, ready to be folded into action.

I made coffee, black and thinking. I sat at the wooden table with a legal pad, and the pen made a sound like a small animal running in snow. Notes:

— Pine Ridge Estates HOA: request docs (bylaws, covenants, enforcement schedule, election procedures, fine ledger).

— County recorder’s office: verify filings (meeting minutes, board rosters, notices).

— Incident report: obtain copy; file formal complaint re: false report.

Outside, the lake lifted steam as the sun took a breath. I checked my phone: three messages from friendly strangers I’d met the day before—Tom from two cabins down, who had shook my hand and said, “Robert? Good man.” Christy from the next street, who had “Weed Killer Killed My Lawn” lodged permanently in her HOA file because she’d complained at the wrong volume. Old Mr. Gilchrist, who had told me Linda once fined him for an “unauthorized birdhouse” and then asked if she could use his bathroom during an emergency board meeting.

You cannot regulate people into good neighbors. You can, however, dislodge tyrants from their clipboards.

Later that morning I walked the property, coffee in hand, shoes sinking into ground that remembered everything I’d forgotten. The canoe rack leaned like a question. The dock was unmoved by the season. I found the spot where Robert had taught me to skip stones and failed to make them do anything but plop like short sentences. I let the grief come, not as a wave, but as a tide. The cabin was loss and relief and inheritance and test.

By noon I had emailed my office and requested the Pine Ridge file be pulled from the stack. The staff attorney, Liz, replied with a string of PDFs and a note: “Been meaning to show you this HOA—lots of smoke, can’t find the fire.” I read:

— Fines for “aesthetic disruption” (undefined).

— Elections held on weekdays at 11:00 a.m. in holiday weeks.

— Blank proxies gathered by board members door-to-door.

— Meetings with no posted agendas.

— Complaints about a president who liked to remind people that “rules exist to be obeyed.”

I called the county recorder. The clerk—tired, efficient, living proof that government is held together by underpaid saints—confirmed that Pine Ridge had filed its governing documents more than a decade ago and paid its annual fees irregularly. Some amendments were missing proof of notice. The last election notice on file was from three years prior. “We don’t police them,” she reminded me. “We just store the paper.”

“I know,” I said. “I police them.”

I went back to the city the next afternoon. The highway unwound, and the cabin receded in the rearview, a white smudge past the trees like a secret you aren’t obligated to tell.

Back at my desk, I did what I do best: read until the truth lined up, then walked it into daylight. Our commission’s authority isn’t glamorous—we don’t cuff people, and we don’t seize yachts—but it’s stubborn and patient. We enforce the laws that keep HOAs from becoming fiefdoms. We inspect elections, audit fines, demand disclosures, and teach the one fact that terrifies tyrants: process is power.

I scheduled a compliance audit for Pine Ridge Estates. State statutes require HOAs to:

— properly notice meetings,

— conduct elections according to their documents,

— maintain financial records available to members,

— enforce rules uniformly,

— and never, ever use law enforcement as a cudgel in a civil dispute.

You’d be amazed how many boards confuse the bylaws with the Bible and treat amendments like parables no one is allowed to interpret but them.

Before the audit date, I drove up on a Saturday and saw Tom out with a paintbrush, applying stain to his deck, a color that looked exactly like all other colors when it came to wood: brown enough to make Linda argue. He waved me over.

“You’re back,” he said, as if the lake had invited me. “You hear about Linda?”

“What about her?”

“She tried to fine me again for the stain. I showed her the can with the exact brand and name from the approved list. She said my deck looked too ‘spirited.’ I said my deck wasn’t a Labrador.”

Christy leaned over her porch rail from three doors down and added, “She made me move my hanging plants because they ‘interfered with the line of sight of community aesthetics.’ I said the only line of sight she should worry about was the one between her and a map.”

Mr. Gilchrist appeared on his steps clutching a birdhouse shaped like a lighthouse. “She said this is ‘coastal.’ I said I visited Florida once; does that make me coastal? She said yes, so I took three laps around the block and told her I was continental again.”

Neighbors in HOAs talk in jokes to avoid going hoarse. The laughter wasn’t happy. It was tired and practised.

“Audit’s coming,” I told them.

Tom looked at my face and did the math. “Good,” he said. “Bring a broom.”

Part III: The Audit, the Meeting, the Fall

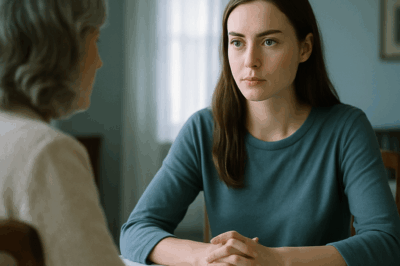

The audit took place in a conference room the color of waiting. The Pine Ridge board sat along one side: Linda with her lips pressed into a decision, two men who looked like they’d been told to bring calm and had brought their schedules instead, a secretary who seemed both exhausted and relieved to see me.

I asked for minutes. I asked for notices. I asked for the policy that authorized a $150 fine for “whimsical garden art” and a $300 “processing fee” for appealing any violation to the board that had issued it. I asked about elections that happened with leftover cupcakes and proxies signed in pencil.

“You’re not a resident,” Linda said, forgetting last week. “You don’t get to ask questions.”

“I’m both,” I said. “A homeowner and the state official tasked with enforcing the laws that keep you from inventing governance.”

She sat back like the chair wasn’t on her side.

When people who are used to obeying themselves meet process, they mistake it for punishment. My questions were polite, precise, and uninterested in her performance. The secretary brought documents. Many had gaps where the facts should be. Some had signatures that looked like the same pen had run marathons. A few had dates that leaned into holidays like a trick.

In the days after the audit, the commission issued a formal notice of violation to Pine Ridge Estates. It wasn’t dramatic. It didn’t use big fonts. It simply listed everything that had been done wrong in the last three years and required the board to do it right. Deadlines. Remedies. A warning about fines that would apply to the HOA, not the members, if compliance wasn’t achieved.

Then came the emergency meeting.

I showed up as a homeowner and took a seat in a folding chair that still smelled like the church basement it had belonged to in a previous life. The room filled with neighbors who had carried their grievances alone until someone named them.

Tom spoke first. Calm. Detailed. “The board fined me $200 for a stain color that was on the approved list. I had to take a day off work to prove that brown is brown.”

Christy read from a notebook. “I was fined for ‘excessive seasonal enthusiasm’ because I put up lights after Thanksgiving. The fine was $50 per night, multiplied until I took them down.”

Mr. Gilchrist, holding his birdhouse like a passport, said simply, “I’m eighty-one. It’s a birdhouse.”

Other voices piled on: fines for trash cans visible for sixteen minutes after pickup; a woman charged $100 because her nephew’s car had a bumper sticker board members deemed “discordant”; a man ordered to remove a ramp built so his wife could get into the house after knee surgery because it “disrupted the symmetry of our sidewalk community.”

Governance is not a personality. It’s a process. Pine Ridge had confused the two so completely they’d built a religion around a clipboard.

The secretary—bless her quiet courage—read the results of the vote to remove Linda from the board. Unanimous, except for one.

“This is illegal,” Linda said, clutching the gavel like a relic. “I have given my life to this community.”

Tom gestured to the ballots. “It’s legal. And it’s time.”

Security didn’t drag her. They guided a woman whose identity had been built on power to a doorway where there was none. She left with her clipboard and a face that looked like an empty file.

The commission levied a civil penalty for the false police report. A county prosecutor considered more and declined, citing mercy I didn’t argue with. The $5,000 fine stung. The 200 hours of community service drew its own small circle of justice. The HOA’s insurance carrier shrugged at covering her defense costs, citing the policy’s exclusion for intentional misconduct. Word in Pine Ridge is that she mortgaged the home she once weaponized to pay the lawyer who could not save her title.

Tom was elected interim president. His first act: repeal of the “whimsical garden art” policy and adoption of an actual due process standard for fines. His second: install a bench by the lake where arguing about stain colors is prohibited by social norm. He invited me to say a few words at the next meeting about the new state guidelines. I stood under fluorescent lights and talked about fairness like it wasn’t old-fashioned. People listened the way thirsty people drink water.

I drove back to the cabin that night, parked by the pines, and stood beside a water that had never once asked for permission to be what it was. The porch light warmed the boards. The new lock clicked like punctuation. I slept the way you do after a story finds its ending and leaves the room.

Part IV: The Protocols

Six months later, the task force tasked me with something that felt both obvious and impossible: write guidelines to keep HOAs from becoming Linda. We called them protocols because that’s what they are. The name other people chose was The Morrison Protocols, which felt like a joke and a responsibility.

The protocols weren’t poetry. They were better. They require:

— elections at accessible times and locations, with notice methods that meet members where they live;

— clear, published fine schedules with appeal rights that aren’t “write a letter to the person who fined you”;

— financial transparency that isn’t a rumor;

— limits on architectural review committees that think aesthetics are a morality play;

— training for board members that teaches the difference between a neighbor and a subject;

— and a hard, bright line: law enforcement shall not be summoned for civil disputes. Disagreements about birdhouses will never again stand next to burglary on a dispatch board.

We held hearings. Homeowners showed up with files and stories and, sometimes, casseroles bearing the organized rage of a good kitchen. Board members showed up with concerns and learned that compliance isn’t a punishment. It’s a floor people can stand on without falling through. I taught, gently and often, that a rule you love is still only a rule if it survives process.

Back at the cabin, fall set the pines on fire without burning them. The lake turned from mirror to ink and back again depending on what the sky needed. I saw Linda sometimes, three streets over, mornings and evenings with a Pomeranian who didn’t know he’d been walked past a revolution. She looked past my property the way people watching their past learn to avoid looking at themselves; head turned, eyes unfocused, apology forming and failing.

One afternoon in October, I caught her paused at the corner where our roads meet. She glanced up. I lifted a hand in a neighborly half-wave. She dropped her eyes and moved on. There are apologies that will never arrive. I stopped waiting for that kind long before the winter came.

Tom ran meetings fairly and made enemies only of the minutes. The board funded dock repairs and left the deck stain list alone. The bench by the lake became a place where people said hello again because no one was writing it down. Christy’s lights went up the day after Thanksgiving like a forgiveness. Mr. Gilchrist’s birdhouse acquired a matching mailbox. It is adorable and, importantly, none of my business.

Each spring, Pine Ridge now receives a notice of its annual compliance review, with a schedule of the documents we’ll inspect. The letter is routine. The signature at the bottom is mine. Linda, I am told by the same grapevine that feeds all small towns, turns pale when the envelope arrives.

Part V: The Night That Started the Ending

On the anniversary of the false report night, I sat on the same porch steps. The light was different: more gold than blue, the kind of evening that thinks a person might fall in love with themself and get away with it. I had a book in my hand and my uncle’s pocketknife in my pocket and a feeling that didn’t ask to be labeled.

I thought about the first knock that morning, the foot jammed against the door, the voice promising to call the police if I slept on the wrong pillow. I thought about the mistake she made later when she called 911 and said the word burglary without understanding gravity. I thought about the way the officer’s voice had shifted when he saw the second card and realized the story wasn’t the one he’d been summoned to perform.

Linda had expected the world to be an extension of her clipboard. Instead, she learned that the world is wider than any person’s preference—and that the law is a boundary that protects the quiet as fiercely as it protects the noise.

Inside the cabin, on a shelf above the sink, a small jar holds a handful of screws whose jobs have been completed. Every time I fix something here, I keep the retired hardware. They’re not trophies. They’re proof that things can come apart and still hold together again differently, sometimes better.

The cabin is full of those proofs. The new lock that replaces the old one, a little scuffed from use. The patched screen on the porch door that once gave a tragedy major air time and now gives only flies a way out. The paint on the trim that blurs the line between the thing as it was and the thing as it is.

The lake doesn’t care about any of it. It takes whatever sky it is given and makes it seem intentional. There is a lesson there, one my uncle taught without saying it: choose your reflection.

Part VI: Neighbors

Tom brought beer one evening and we sat on the bench by the lake he funded with fines he didn’t impose. He’s the kind of man whose hands always have a small job, even when he’s resting: flipping a bottle cap, straightening a label, sketching deck railings on napkins.

“You saved this place,” he said. “You know that, right?”

“I did my job,” I said. “The people saved it.”

“Then we’ll share the credit,” he said, with the generosity of the practical.

Christy wandered down with a blanket and a plastic container of cookies that had the faintest taste of nutmeg. She told a story about her nephew and a frog and the kind of summer joy that makes time feel like a real thing and not a work product. Mr. Gilchrist ambled by and sat on the far end of the bench and didn’t say anything at all. We looked at the water like we’d been hired to keep it safe by watching it. I don’t think the lake needed us, but it didn’t mind.

Two cabins over, a couple put a pair of Adirondack chairs on their dock that were not on any list and never will be. They painted them a blue the sky envied at certain hours. No one complained. There’s a rule in the new Pine Ridge about how long you can stare at someone else’s life before you must return to your own.

Part VII: The Call and the Card

That winter, the office phone rang and the dispatcher announced a caller who wouldn’t give her name. The voice that came through was small and brave.

“I’m on a board,” she said. “We think our president is… making rules up.”

“Okay,” I said. “Tell me.”

She told me everything. It was a story I knew by heart that still hurt when it arrived. I sent her the protocols. I sent her a letter template. I sent her courage disguised as paperwork.

“Thank you,” she said at the end. “I’m scared.”

“You’re doing it for everyone who lives there,” I said. “You don’t have to do it alone. The law is your neighbor.”

The card with my signature went out in the mail two days later. I pictured someone, somewhere, opening it and recognizing a road out.

Part VIII: Who I Am

People assumed Linda froze when she learned who I am because of the title. But that’s not the truth I carry. The part that matters most is that the card confirms I exist in a way she couldn’t write around. It says that the quiet man on the porch with a mug in his hand has a job she can’t perform with a gavel and a clipboard. It says the law belongs to people who sleep in their own beds as much as it belongs to those who like rules. It says neighbors get to be neighbors.

Who I am is a boy raised by a man who taught him how to tie lines and untie knots. A public servant who chose the slow power of process. A homeowner who knows what it feels like when a door is pounded at dawn by someone who doesn’t know or care what’s on the other side. A person who believes that law, at its best, is a shape that prevents the worst people from making everyone else small.

Who I am, also, is a man who sleeps exceptionally well at a cabin by a lake because a woman once called 911 on me for sleeping there—and learned, the hard way, that process is stronger than posture.

Part IX: The Ending

On a spring morning, the annual HOA compliance letter went out to Pine Ridge Estates. I signed it with the same pen I’d used to underline the part of my uncle’s will that said “to Daniel, the cabin by the lake.” Tom texted a photo of the envelope: “Arrived. See you at the review.” Christy sent a picture of her new garden gnomes with the caption “whimsical and lawful.” Mr. Gilchrist mailed me a postcard with a drawing of a birdhouse that had somehow acquired a chimney.

I walked down to the dock with my mug and watched the sun practice being summer. Across the water, a loon called, and the sound ran along the surface like stitching. The bench sat where it sits now, waiting for all arguments to become stories, for the noise to lower enough that we can hear ourselves breathe.

Somewhere, a Pomeranian barked at a squirrel that didn’t care. Somewhere, in an office that used to be a throne, a clipboard hung lonely on a nail. The Morrison Protocols existed in the world like the opposite of a warning. They weren’t mine, not really. They belonged to anyone who needed them.

When the breeze moved through the pines, the needles made a sound like applause you can’t track the origin of: soft, steady, unforced. I took a drink of coffee that had cooled and didn’t mind. I thought of Uncle Robert, and for once the memory didn’t land like a wave but like a hand on my shoulder.

This is the ending: the lights flashing on knotty pine, the clipboard rising and falling, the officers asking for ID, the moment a story rewrote itself under the pressure of a card. A complaint filed, an audit scheduled, an election that made room for people to breathe. A woman learning the border between her preference and the law. A community setting a bench by the lake and choosing to sit.

I turned and went inside to pack a bag for the drive back to the city. I locked the door—not out of fear, but out of ritual. The new bolt slid home with that crisp, satisfied sound. I left the cabin neat, the way Robert taught me: dishes done, fireplace cold, lights off, coffee grounds emptied into the compost. I patted the doorframe where he’d carved those fish that got away. Then I walked down the steps, past the mark Linda made by mistake and the marks made on purpose by everyone who lives here now.

The lake kept reflecting the sky. The sky kept pretending it was new. I got in the car and drove, certain as a deed, steady as the road home.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

When is THAT ONE time that you had to turn to the dark side?

When is THAT ONE time that you had to turn to the dark side? Part I — The Unicorn…

“We’re Taking Your Lake House For The Summer!” Sister Announced In A Family Group Chat. I Waited…

“My sister said, “We’re taking your lake house for the summer,” and everyone in my family agreed. They drove six…

My Mother Asked Who I Wanted To Marry. This Time, I Didn’t Choose Simon Hughes…

My Mother Asked Who I Wanted To Marry. This Time, I Didn’t Choose Simon Hughes… Part I: The Answer…

When did you FIRST realize that your parents were bad at parenting?

When did you FIRST realize that your parents were bad at parenting? Part I — The Night the House…

HOA Karen Tried to Fine Me for Drinking Coffee in My Front Yard!

HOA Karen Tried to Fine Me for Drinking Coffee in My Front Yard! Part I: The Violation The morning…

My BROTHER got me KICKED out of the house so he could use my room as a game room…

My BROTHER got me KICKED out of the house so he could use my room as a game room… …

End of content

No more pages to load