HOA Demolished My Lake Mansion for “Failing to Pay HOA Fees” — Too Bad I Own The Entire Neighborhood

Part 1

The RV’s old diesel had a lullaby to it I’d come to love—low and steady, the sound of steel agreeing to keep its promises. Six weeks on the road visiting my daughter and her kids had been worth every mile through corn, canyon, and blown-out August heat. But even joy has a center of gravity. Mine was a sliver of lake tucked behind a stand of loblolly pines and a wide-porched house I’d built with my own hands twenty-two years earlier. The gravel of my private drive gave that familiar crunch under the tires—the sound that always meant I could finally put the world down.

Then I smelled it.

Not wood smoke from a neighbor’s first fire of the season. Not rain lifts-dust into the air. This was bitter, a cocktail of diesel, powdered gypsum, and the chalky aftertaste that hangs over a disaster. I knew it before my brain admitted it. Thirty years as the county fire chief had set certain scents into my bones. This was the smell of things coming apart on purpose.

The sun hadn’t cleared the pines yet. Long morning shadows lay across the water like dark velvet. As I rounded the last bend, my foot eased off the gas without asking me, the way you do when something in front of you is not the shape it should be.

There, where my front lawn should have been, sat a big yellow excavator, its boom resting in a pile of splintered studs and torn shingles. Men in hard hats moved like ants over a carcass. A bulldozer idled with that sullen arrogance only heavy machinery has. My house—my heavy timber, triple-hurricane-tied, overbuilt-on-purpose house—was a pile.

I don’t remember putting the RV in park. I do remember the hollow thunk of my boots hitting the gravel and the way the air seemed to tilt.

One wall still stood—half the living room, a slice of drywall like a crooked tombstone. I could see through the open wound where the kitchen had been straight to the lake, calm and indifferent. The big cast iron farmhouse sink I’d installed with my brother-in-law back when we were both young enough to lift stupid things sat twisted like scrap art. And then my gaze snagged on a shape under a layer of smashed sheetrock: dark wood, a curve I knew as well as I knew the sound of rain on that roof.

My wife’s piano.

The lid was cracked, the white keys scattered like broken teeth across the debris. I could hear her anyway—her fingers finding “Autumn Leaves” at twilight with the sliding door open and the geese complaining on the water. She’d played it every evening until she couldn’t. I had bought it for our twenty-fifth anniversary because I was a fireman who married above his station and wanted to give her something beautiful to put her hands on in between raising our daughter and making sure I remembered to eat.

Now it was trash.

“Sir, you can’t be here. This is an active demolition site.”

Clipboards have a way of believing they are shields. The man who walked up to me had one tucked against his chest and that tired supervisor look—already behind schedule, already out of “sirs” for the day. The vest was clean. The boots were not.

“This is my home,” I heard myself say in a voice that sounded far away and too calm. “What is going on?”

He sighed, flipped a page. “Notice was posted three times. First one went up six months ago. You didn’t pay your HOA dues.”

The words didn’t make sense pressed together like that. I let them sit. I let the shock burn off into something colder. The part of me that had walked fire grounds while neighbors screamed had learned a long time ago how to keep a voice flat until the facts arrived.

“I am not in any HOA,” I said. “I own twelve acres. My property line ends a quarter mile from Heron Creek Estates.” I met his eyes. “I made sure of it when the developer came through.”

“You are now,” he said, tapping his clipboard. “They annexed you.”

He said it like announcing rain.

Annexed. The word sat in the air like a faulty wire sizzling somewhere behind drywall. You can’t see the spark, but you can follow the smell.

Twelve years earlier, a developer had bought two hundred acres of old farmland across the way and carved it into a curlicue river of cul-de-sacs and pocket parks named for trees that used to be there. He’d offered me a small fortune for my twelve acres because developers always think money can flatten grief and shape land. I’d said no, because my wife and I had buried our grief here and built our marriage on top of it and you don’t sell that for granite countertops and an HOA newsletter.

He and I had come to an agreement. We walked the lines with surveyors and hammered iron pins deep enough to outlive us all. He filed his tract map with a bite missing where my land sat. I filed my own parcel map and deed. Different parcel number. Different tax bill. Different world. I’d watched them pour sidewalks and build houses with mailboxes that matched and a pool that looked too clean to be true. They formed an HOA and printed covenants as thick as a Bible and not half as forgiving.

I hadn’t been on a single page of that book.

“Stop,” the foreman finally shouted over my shoulder at his crew, realizing I wasn’t going to get out of the way and maybe someone with more authority than a clip would be curious if they knocked a fire chief on his rear. “We’ll pick up after lunch.”

Engines idled down. Dust hung. The silence had weight.

My mailbox at the end of the drive was stuffed with the usual—flyers for pest control, a catalog that still had my wife’s name on it six years after, a couple of bills—and two envelopes official enough to make your stomach do a thing. Both were from “Heron Creek Estates HOA.”

The first was a certified letter, the green return card still stapled to it. Inside—legalese and threats: six months of unpaid HOA dues plus late fees. $2,946.18 due within ten days to avoid a “lien and compliance action.”

The second was a photocopy of meeting minutes. A paragraph circled in red: a vote taken to “retroactively annex” my parcel into the HOA “to ensure aesthetic cohesion for the community’s lakefront view.”

They had voted to draw a new boundary around my life while I was somewhere in Kansas teaching my grandson to skip rocks. The sentence got under my fingernails.

I called the county. “Records,” a cheerful voice picked up. I gave my parcel number and asked if anyone had condemned my house while I was gone.

“No, sir,” she said after a minute of keyboard keys like rain. “Nothing like that. Your taxes are current. Certificate of occupancy clean.” Her voice slowed. “But I do see a demolition permit. Pulled by…Heron Creek Estates HOA.”

“You have my authorization on file?” I asked.

“Of course,” she said. “Owner’s signature is required for demo.”

The PDF of the permit hit my email while we were still on the phone. I opened it at the little dinette table in the RV. There, in the box labeled Owner Authorization, was my name, Jack Whitaker, written in my hand. Only it wasn’t. The curve was too clean. The line weight too consistent. I felt a memory arrive like a pry bar. Ten years ago a hailstorm had beaten the roof like a drum. The county had a new digital pad then. I’d signed my name on it with a pen that forgot it was a pen halfway through. The signature on the old roofing permit file was identical to the one on the new demo permit down to the pixel.

They hadn’t forged my signature. They’d stolen it.

“Who uploaded this?” I asked the clerk.

“Sir,” she said, and I could hear the bureaucrat in her fighting with the human, “I’m not supposed to—”

“This is Jack Whitaker,” I said, letting thirty years of command settle into the sentence. “I was fire chief in this county from 1987 to 2017. People used to look to my signature to tell them their family wasn’t going to burn in the night. I need to know whose hands are dirty.”

There was a long pause. Then the voice went quiet and kind. “I’m emailing you the file properties,” she said.

Metadata—the file’s fingerprints. The permit had been created at the county office during business hours. Then, three months later, it had been opened, modified, and saved from a home computer registered to a user named “Linda R.” at 2:07 a.m. on a Tuesday.

“Got it,” I said. I laid the phone down, stared at the screen until the black letters started to slide into each other, and felt something settle in me like concrete.

Shock burns off. Rage cools. What’s left is work.

Part 2

My RV has seen storms, floods, and a toddler armed with a Sharpie. That week it became a command post. I made coffee strong enough to strip paint and started where you always start when you’re trying to find the fire: your own house.

I logged into my security system. Five years back, some teenagers with more free time than sense had decided my dock was open to the public. I’d installed three cameras—one on the gate, one on the porch, one on the garage. They recorded to a small hard drive under the stairs and kicked short clips up to the cloud when something moved.

I watched six months of “something moved.” Mailman. Deer. Raccoons organizing a failed heist. No one in a bright orange vest stapling anything to my front door. No one with a clipboard and false confidence.

“Posted notice,” my foot.

Heron Creek had a website straight out of 2008—stock photos of children on bicycles, a calendar with “Yard of the Month,” a link that said “Documents.” I clicked like a man picking a lock with a bobby pin in a rainstorm. By the grace of lazy web admins, an old forum sat preserved inside one of the folders like a fossil in amber.

There she was. “Uncooperative lakefront property,” a thread started by the HOA president, LINDA ROSELL. The tone was the kind you hear from people who’ve mistaken a volunteer position for a throne. She called my house an eyesore, her word. She floated the idea of “bringing him into compliance.” Her friends chimed in—“We have to do something about that view!” A third post from “LindaR”: If he won’t sell, we’ll force a compliance lien. We’ll make it make sense. Trust me, we’ll make it make sense.

I remembered training my rookies back in ‘95: arsonists don’t start fires. They arrange the story so a match can find it.

I sent the PDFs and screenshots to my email twice and printed them anyway, because one thing thirty years in emergency services taught me is that paper will still be readable while your laptop is smoking in a ditch.

Then I called the sheriff.

Sheriff Miller and I go back to the days when scanners lived under our pillows. I went to his office with two thick folders and a look that made his receptionist tell me to sit without asking why I was there.

“Jack,” he said, coming out from behind his desk. We shook like men who have buried enough people together to have earned a little extra pressure in the grip. “I heard. I—hell.” He sat. I sat. I didn’t let my voice rise. I laid it out: no posted notice on camera, HOA forum, forged permit with stolen signature, 2:07 a.m. metadata. He read in silence, his jaw doing that thing jaws do when they’re trying not to speak before the brain is ready.

“Officially,” he said finally, “you file a complaint. We open an investigation.” He slid a paper across the desk. “Unofficially,” he said softer, “this isn’t their first try. Folks called us about bogus fines. Property line ‘adjustments.’ Threats. But when the board’s lawyer sent a letter, they folded. You’re not the folding kind.”

“No,” I said, and smiled without humor. “I’m the kind that sets up a rehab tent and keeps pouring water on men because the work hasn’t done with their bodies yet.”

He reached into a drawer, pulled out a list of names and numbers. “They called us,” he said. “Wouldn’t go on the record. They might talk to you.”

Next, I called a man named Mallister. The world calls him Doug. Firefighters call him Stitch because he can make broken things hold. He patched pump housings in ‘79 when parts were six counties away. Later, he became a structural engineer and made a career out of telling people their houses were fine even when their fear told them otherwise. He’s a Vietnam vet and walks with a limp that doesn’t apologize to anyone.

“Jack,” he said when I told him what had happened. “Got my boots on. Be there in an hour.”

He rolled up in his old Ford like he was arriving to a potluck, thermos in hand, hard hat under his arm. He didn’t say sorry. Men like him don’t waste sorry. He stood on my gravel and looked at my rubble and let his eyes tell him the story the ground remembers.

“This wasn’t a collapse,” he said finally. “This was an execution.” He walked the perimeter, his cane tapping like punctuation. He crouched down, old joints be damned, and ran his fingers along exposed rebar.

“You know what they’ll say,” I said. “Unsafe. Condemned. You know how fear travels in a neighborhood. They’ll make my house into the monster under their beds.”

“They won’t if we take away the story first,” he said. He reached into his truck and pulled out a drone. “Let’s look at what gravity says.”

He flew it low and slow over the foundation. No spiderweb of stress fractures. No heaving. No settling. The slab we’d poured two decades back was still a slab. We printed photos on paper you could practically sand a board with.

He spread my old blueprints on his tailgate and traced the lines. “Half-inch rebar twelve inches on center,” he murmured. “Double-joisted floor supports. Hurricane ties on all rafters. Jack, you didn’t build a house. You built a bunker with windows.”

He poked at the list with a thick finger. “If they pulled a demo permit, they had to file an inspection saying this place was unsafe.” He looked up without lifting his head. “Go get it.”

The county clerk braced when I walked in with that fire chief gait—half apology, half get out of my way. She brought me an “emergency structural inspection report” filed three months prior. “Foundation settling.” “Roof truss instability.” The inspector’s name, typed at the bottom: Bill Johnson.

He spells it Johnsen.

I took a picture and texted it to Stitch. His reply came back: “People who lie always misspell something. Hang on to that.”

Late that afternoon, I found the piano lid half-buried under splinters. A hinge caught my finger. I pried up the thin brass panel where my wife used to tuck her sheet music. Inside, wrapped in a page of her favorite Chopin, was a plastic thumb drive. My wife had been a librarian for twenty-five years before she married a man who smelled like smoke and came home at midnight with stories he couldn’t tell. She believed in archives.

I plugged it into my laptop in the RV. One folder: “For the kids.” Videos. The first one: her face, thinner than it used to be, eyes still wry, the piano behind her. “Hi, monsters,” she said to the camera, meaning our grandkids. She told them about the time their mother ate a ladybug because she thought it was a candy. She talked about the way the lake freezes in a circle first. She looked at the lens like she could see around corners. “Things break,” she said, her mouth softening. “But they can’t take what matters, not from you. What we build inside—that’s the part that survives.”

“Okay,” I said to the RV, to the lake, to the person whose voice had just reached through a wire to hand me back my spine. “Time to work.”

I made packets. Each packet had: county map showing the HOA’s tract with a bite taken out where my land sat; my 2014 roofing permit with my lopsided blue digital signature; the demo permit with the identical black counterfeit; the emergency inspection report with JOHNSON spelled wrong; Stitch’s drone photos; a summary of codes my house had met with room to spare; a printout of the forum post with Linda’s little We’ll make it make sense circled in red; and a single page at the top that said “THIS IS WHAT THE TRUTH LOOKS LIKE” because some folks need a label to know what they’re holding.

Then I charged a little digital recorder the size of my thumb. Not to break laws. To remind the room who had said what when the denial started.

Part 3

HOA clubhouses are the same everywhere. Beige paint. Stackable chairs. A whiff of coffee that tastes like punishment. A whiteboard with “AGENDA” written at the top in a dry erase marker that died two meetings ago.

I sat in the back in my cleanest flannel and watched a woman with a sleek navy pantsuit and a haircut you can set a watch by call the meeting to order with a gavel she loved too much. LINDA ROSELL. Her smile was bright. Her eyes were knives. She denied a neighbor’s request for a bougainvillea because it wasn’t on the approved list. She lectured a man about his mailbox. She used “aesthetic cohesion” like most people use “please.”

When she finally called for “New business,” I stood.

She saw me and did that little flicker women like her do when something they thought they had solved reappears in a doorway—surprise, anger, then the face. “Mr. Whitaker,” she said into her microphone. “This meeting is for members only.”

“I’m not here as a member,” I said, walking forward with a stack of packets. “I’m here as the owner of the property you illegally demolished.”

Gasps are a cliché because sometimes a room really does inhale at once. I laid the packets on the table in front of her and passed the rest down the line, resident to resident, the way you pass communion in a church that can’t afford a minister.

“Page one,” I said. “County map. My parcel. Not in your tract.” A murmur. “Page two: my real signature in 2014. Page three: your forgery in 2023.” Heads snapped up and then down again. “Page four: emergency inspection you filed. Inspector’s last name spelled like a man who doesn’t exist.” Someone in the front row whispered, “Oh, my God,” in the tone people use when the thing in front of them refuses to be explained away.

Linda flipped. Her mouth made that tight smirk you practice in a mirror when you want to look like you’re winning. Her lawyer—a man in a shiny suit with shoulders big enough to be rented by the hour—stood to puff.

“This is a violation of privacy,” he said. “None of this will be admissible. Sir, you are trespassing.”

I smiled. Just a little. “That’s fine,” I said. “I’m not going to court.”

The silence went weird and pregnant. The lawyer’s eyes flicked. He knew exactly what sentence might be coming and hated it already.

“I’m going to title.”

He didn’t sit, but something in him sagged. The residents’ faces said what? The lawyer’s face said oh no.

“You see,” I said, keeping my voice flat like a line on a map you can trust, “when the developer went bankrupt twenty years ago, they sold the lots to builders and families.” I looked at the room, not at Linda. “I bought different assets.”

Linda laughed, a brittle chime. “The HOA owns the commons,” she said. “The park. The roads.”

“No,” I said politely, as if correcting a child who’s just told you the sky is green because it wants to be. “You were granted easements.” I held up a copy of the recorded document. “An easement means you get to use land you do not own for a specific purpose. The road you call Heron Creek Lane? Built on land I own. The water lines? Buried in dirt I own. The sewer? Runs through my field.”

I let that sit so the older gentleman on the end of the board could feel his chair scoot back an inch on its own.

“As of eight o’clock this morning,” I continued, “my attorney filed to terminate your easements for violation of the agreement.” I tapped my packet. “Demolishing the home of the man who granted you use of his road isn’t ‘aesthetic cohesion.’ It’s a catastrophic breach.”

The woman in the front row—blonde, tight smile, a kind of courage in her eyes I didn’t yet trust—blurted, “You can’t! We’ll be trapped!”

“I’m a reasonable man,” I said. “For forty-eight hours, residents come and go. After that, a gate at the entrance. Get your groceries.”

Now the room made a noise I’ve only heard at scenes where someone turns on the hose and no water comes. Panic. Anger. The lawyer sat down like his knees had forgotten witchcraft. Linda blinked like someone had flashed bright light.

“I’ve also sent letters to your contractors,” I said over the rising noise. “Your landscaper? No longer allowed to mow on my road. Private security in the fake police car? Not on my property. Demolition company? Informed their work order was based on forged documents and their equipment is on my land.”

A man stood abruptly—wiry, tired, with a woman beside him whose shoulders had settled into the kind of slope you get from carrying someone else’s body up a flight of stairs. “Mr. Whitaker,” he said. “They denied us a ramp. Said pressure-treated lumber wasn’t ‘in harmony.’ My mother-in-law can’t leave the house.”

“Get a county permit,” I said loud enough for every recording phone to pick it up. “Build your ramp. If anyone here tries to stop you, they trespass on your property and mine.”

Small hope moves through a room like heat. People turned. Linda, finally understanding that her power ran on paper someone else owned, started to sputter. “Illegal! You can’t—this is harassment!” The lawyer tried to find a legal word he could throw like a net and came up with none.

I took a little digital recorder out of my pocket and set it on the table. “One last thing,” I said. “I brought you a voice from your own forum in case you want to hear what you sound like.”

I pressed play. Linda’s own chirpy confidence filled the beige room: “If he won’t sell, we’ll force a compliance lien. We’ll make it make sense.”

There are sounds that mark turning points. Clicks. Pops. The moment a nail lets go, the moment a heart quiets, the moment a lie slides off the table because there’s not enough friction left to hold it.

The older board member picked up his chair, as if manners still mattered, and walked out quietly. The residents didn’t look at me. They looked at Linda.

Things move fast in small places once someone admits gravity exists. By morning, the residents had called a meeting without the board. By lunch, they’d voted the lot of them out. By dinner, the HOA had no one to sign checks. But a decapitated snake still carries poison.

Two days later, as a crew sank posts for the gate at the entrance to “Heron Creek Lane,” two sheriff’s cars pulled up. Linda sat in the passenger seat, pointing like a cartoon villain. She had filed a complaint that I was “unlawfully obstructing a public roadway.”

The senior deputy got out slow. He had that look cops get when they’ve been told this is nothing and the part of them that’s still human suspects it is not nothing at all.

“Sir,” he said. “We got a call. You blocking a road?”

“Maybe,” I said. “Let me show you something.”

I led him into the RV and laid out the plat map and title like a dealer laying down a good hand. The officer traced the lines with his finger. He read the easement grants. He read the termination. He read the forged permit and the copied signature. He saw JOHNSON spelled wrong and the metadata with 2:07 a.m. and a home computer named LindaR.

He went back to his car, radioed, waited. When he returned, his face had changed. The weight had shifted from annoyance to duty.

“Mr. Whitaker,” he said, “with the forgery and use of the mail…this is federal. We’re calling the Bureau.”

Linda’s mouth opened. Then closed. Then opened. Words did not take.

Part 4

Federal men in windbreakers don’t make speeches. They make calls, they make lists, and sometimes they make arrests at the most humiliating possible moment.

Three weeks after the bulldozer made a grave of my living room, the FBI walked into an HOA meeting that residents had called to figure out how to dissolve the very machine they’d built to keep their grass three inches tall. An agent in a navy jacket said, “Ms. Rosell?” in a tone that made three other women in the room sit up straight. He put cuffs on her thin wrists. There’s a sound handcuffs make when they close that is both final and incredibly petty. They walked her past the table where she had once told her neighbor his petunias were obscene.

Her secretary folded first. “Angela Meyers,” who had kept minutes and notarized signatures, broke open like a bad seam the minute she saw the agents’ folder with her name tabbed inside. She admitted Linda had told her to “fix” digital documents. She admitted Linda had told her to “rewrite boundaries” to bring my parcel into the HOA’s “jurisdiction.” She admitted the plan had been to make me sell once I was “non-compliant” and “fined beyond reason.”

The insurance company for the HOA took one look at the pile I’d stacked and decided their appetite for risk was smaller than their appetite for writing a check. We settled civilly without seeing the inside of a courtroom. $948,200. Replacement value of a house. Punitive damages for audacity. Attorney’s fees. I took the check to my credit union and then took myself to the diner where the waitress calls everybody “honey” because she’s earned the right.

“Jack,” she said, setting a plate of meatloaf in front of me heavy enough to anchor a pontoon boat. “Heard about your house. Heard about your check. You going to rebuild?”

“Yes,” I said. “And no.”

She cocked an eyebrow the way women of a certain age do to encourage men who take too long to get to the point.

“Yes, same footprint,” I said. “Same porch. No—better. Ramp. Safe room. Piano room, even if there’s no piano.”

“Good,” she said. “Bring me a photo. I’ll put it on the board next to the kids who catch big fish.”

We set the forms aside for a new kind of neighborhood. The HOA died because everyone who could keep it alive had either been indicted, humiliated, or had the sense to admit you can’t run a community like a kingdom without a treasury. The residents formed a voluntary road association. No “architectural review committee.” No fines for shade of taupe. Just a simple agreement: everyone pays a little when the road needs gravel. Everyone pays a little more when the potholes get big. We used a mason jar and a spreadsheet and a lot of stubbornness.

Mr. Miller—the man with the mother-in-law—called me on a Saturday. “Got the permit,” he said. “Still don’t know the difference between a carriage bolt and a lag screw.”

“Bring your coffee,” I said. “We’ll do it in a day.”

We built that ramp together. Stitch showed up with a box of decking screws and the righteous attitude of a man who still can’t stand bullies. He argued with me over whether the posts should be four by sixes or six by sixes and I let him win because he had earned a couple of easy victories in his life. We sank them deep. We put the handrail a hair higher than code because the woman who would hold it was small and would want to lean. We stood back, and the Millers cried the way people cry when the thing they’ve needed for too long finally exists in the world.

Linda pled out. Mail fraud. Wire fraud. Filing forged instruments. Conspiracy. She avoided prison but did not avoid the thing that would hurt her most: the people who used to avoid her gaze in the grocery store now looked her right in the face, and not with fear.

I rebuilt. The crews came early and left late, the way good crews do when they like the man signing their checks. My new house looked like the old house because the old house had been right. The change was in the bones where nobody would see it—extra rebar, hurricane clips, a room under the slab with a six-inch steel door for tornadoes and, if I’m honest, my peace of mind. And at the top of the stairs, a small room with windows for light and no doors for closing where the piano would have gone if life had allowed one more miracle.

I asked the road association to meet at my place. They came with folding chairs and casseroles because this is still America in ways that matter. We signed our names and agreed to watch each other’s kids and dogs on days when storms would come whether any of us felt up to it.

“Mr. Whitaker,” a woman said, the blonde from the front row with the brittle smile now softened, “the school bus?”

“I talked to the superintendent,” I said. “They’ll pull a turnaround at the gate. I’m installing a keypad. Everyone gets a code. UPS can figure it out. If they can’t, they can drop it at Mindy’s because she likes seeing people.”

Laughter around the table tells you a neighborhood is working again. We laughed. We put money in a mason jar. We went home.

Part 5

On the day the framing crew set the last truss, I brought a cooler full of water and a finger of whiskey in a coffee mug and stood in the yard like a man in a Norman Rockwell painting. The hammering stopped. The men climbed down. The crew chief came over with the respectful swagger some people can carry without it feeling like a threat. “You gonna sign the ridge?” he asked.

“I am,” I said. He handed me a Sharpie—the only pen that matters on a job site. I climbed the ladder like a grandfather who still believes gravity will forgive him. I wrote: For E., who played the lake into evening. For K., who will bring his boys here when they need quiet. For anyone who needs to sit. —J.W.

When you sign your name to wood that will be covered by drywall, you are making a treaty with the future. It will never know what you said, but it will feel it anyway.

The day I moved back in, the sun came up over the far end of the lake the way it always had—surprised to find water waiting to catch it. I opened every window. The house breathed. I made coffee. I walked through every room like a man taking attendance. Kitchen present. Stair rail present. Bedroom present. Small room at the top of the stairs where a piano used to live present.

I took my wife’s thumb drive out of the little fireproof box I keep under the bed. I plugged it into the second drawer of the desk because that’s where the laptop sits now. I watched one of her videos. “Kids,” she said, eyes mischievous, “you don’t know this story: your grandfather asked me to marry him on the duck blind because he thought the ducks were pretty and I thought the way he asked was prettier. I said yes because I knew he’d never stop showing up.”

“Okay,” I said out loud to a room that didn’t need me to narrate. “Okay.”

Word traveled in the county without Facebook’s help. People stopped by. They brought pie. They brought their own stories. The man who had scolded me at the meeting for threatening to “trap” them brought his little boy to fish off my dock. “I didn’t know,” he said, embarrassed. “You didn’t, either,” I said. “That’s why we keep paper.”

The sheriff’s office sent a young deputy—new boots, careful eyes—to ask if I would talk to recruits in a training block about “de-escalation.” I told him I didn’t know anything about de-escalation. He said, “You kept a riot from happening in a beige room with a Sharpie and a plat map.” I told him to bring coffee.

The FBI agent—turns out his name is James and he likes baseball as much as I pretend to—emailed me an update. Cases like that churn like a slow river—never as fast as you want if you’re the one who got wet, faster than the water thought it would when it’s trying to eat a bank. “We closed it,” he wrote. “Thank you for doing our job before we did.”

“Pay me,” I wrote back. He sent me a smiley face and then a link to a fund for people whose houses get demolished because men with clipboards lie loudly enough. I sent a check. It wasn’t much. It didn’t need to be. It reminded me that grief can be converted into something besides more grief if the right two hands hold it for a moment.

On a slow afternoon—the lake glassy, the wind taking a personal day—Mr. Miller wheeled his mother-in-law down the ramp we built and parked her on the porch. She looked at me with the suspicious kindness of women who have lived long enough to have learned not to be fooled by men’s sudden bursts of competence.

“Thank you,” she said in a voice that had once cut wood with its volume and now stayed soft to keep from breaking.

“You don’t owe me that,” I said. “Linda does.” We both smiled like two people who know they are not supposed to gossip and do it anyway.

At dusk, I sat in the chair where my wife used to play, put my hands where hers had been on the air, and listened to nothing. Sometimes nothing is exactly the sound you need to hear to know you have won. Sometimes victory looks like the mail going where it’s supposed to, the road holding under the school bus, the lights staying on because you paid for the pole the wires sit on, the ramp holding under two sets of feet.

People think power is paper. Covenants. Fines. A title with your name on it in a font someone picked in a conference room where they argued over the shade of beige to print it on.

Power is the ground.

It is the piece of dirt you stood on when someone tried to move your house and you said, “No.” It is the map you carry rolled up in your hand like a bat. It is the faces of neighbors who learned in a beige room that a woman with a gavel doesn’t get to tell a county where its roads are. It is a ramp. A drone photo. A signature that a man tried to steal and a file that remembered him at 2:07 a.m.

One morning the following spring, I walked down to the gate I’d installed at the head of Heron Creek Lane. It stood open, keypad blinking in the new light. I watched a line of cars—school drop-offs, a contractor’s van, a woman who is always late to everything but church—move through the way blood moves through a vein. The road didn’t belong to them. It didn’t belong to me. It belonged to the fact that we had decided together not to lie about whose it was. That was enough.

I turned back toward the house. The wind came up. The pines leaned. I could hear the sound of someone learning “Autumn Leaves” very slowly on an out-of-tune upright across the lake. I walked up my ramp. I put my hand on the rail where hers will never be again. I went inside. I poured coffee. I sat.

“Things break,” she had said. “What we build inside—that’s forever.”

I lifted my mug to the room where her voice used to live. “To forever,” I said. “And to the ground beneath our feet.”

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

They Mocked Her at the Gun Store — Then the Commander Burst In and Saluted Her

They Mocked Her at the Gun Store — Then the Commander Burst In and Saluted Her Part I —…

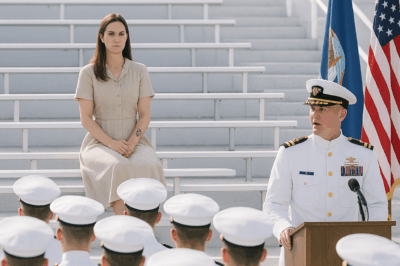

She Only Came to Watch Her Son Graduate Until Navy SEAL Commander Saw Her Tattoo and Froze

She Only Came to Watch Her Son Graduate Until Navy SEAL Commander Saw Her Tattoo and Froze Part 1…

“What’s that patch even for ” then the colonel said,“Only five officers have earned that in 20 years

“What’s that patch even for” then the colonel said, “Only five officers have earned that in 20 years” Part…

My Sister Mocked Me At Dinner “Photocopier Captain?” — Then Dad’s Old War Buddy Saluted Me

My Sister Mocked Me At Dinner “Photocopier Captain?” — Then Dad’s Old War Buddy Saluted Me. At dinner, my sister…

Family Demanded To ‘Speak To The Owner’ About My Presence – That Was Their Biggest Mistake

Family Demanded To ‘Speak To The Owner’ About My Presence — That Was Their Biggest Mistake Part I —…

My husband & I didn’t finish high school & our son’s wife who graduated from an Ivy looks down on us

My husband & I didn’t finish high school & our son’s wife who graduated from an Ivy looks down on…

End of content

No more pages to load