Part 1

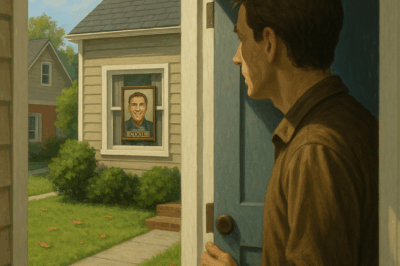

I don’t know where else to put this. I’ve called 911. I’ve broken windows. I’ve tried staying awake all night, skipping town, everything. But every time the clock hits 8:43 p.m., I’m back at the beginning—on the front porch of a quiet house in a cul-de-sac in Maple Hill, holding my backpack and a smile I don’t mean.

My name’s Leah. I’m nineteen. I babysit to pay for school. Usually it’s pretty normal—movies, snacks, putting a kid to bed by 9. This time it’s not normal. This time I think I’m trapped, and the kid knows it.

Her name is Ellie. She’s six. Blonde, big eyes, little voice. She looks like she belongs in a toothpaste commercial.

Her mom, Marissa, hired me off a local app for a last-minute babysitting job. One day only. Said she had a work trip she couldn’t skip. Paid me in cash the second I stepped inside. “She’s been looking forward to this all week,” Marissa said, already halfway out the door. “She says today’s going to be the best day ever.”

I remember that sentence too well now. I’ve heard it over a hundred times.

Ellie was already waiting at the top of the stairs that first morning. She looked at me like she’d met me before. “Are you ready?” she asked.

I asked, “Ready for what?”

“For the best day ever,” she said. Like it was obvious.

It started small. A weird sense of déjà vu. The dog barked before I rang the bell. A breeze blew the exact same piece of paper off the table twice. Ellie started answering my questions before I asked them.

Then I woke up on the porch again.

Same morning. Same clothes. Same words out of Marissa’s mouth. Same look from Ellie. “Are you ready?”

I thought maybe I dreamed the whole day. Maybe I was sick. But the loops kept coming. Over and over. Same date. Same house. Same kid.

At first, Ellie pretended she didn’t notice. But after a few loops, she started slipping up. Calling me by name before I introduced myself. Finishing my sentences. Laughing at jokes I hadn’t told yet.

By the fifth loop, I said, “You know what’s happening, don’t you?”

She grinned. “I just want it to be perfect.”

Perfect. Like I’d been getting it wrong this whole time.

So I played along. I tried things. Took her to the park. Got her ice cream. Let her watch cartoons for hours. Every loop, something new. Sometimes she smiled. Sometimes she frowned. But the day always ended the same way—me tucking her in, thinking maybe this time I’d broken it. Then darkness.

Then 7:58 a.m.

Eventually she stopped pretending.

One morning I woke up on the porch and she was standing outside waiting for me.

“You’re late,” she said.

“I’m two minutes early,” I said.

She looked past me. “Not this time.”

She’s changing. Each loop, she seems older. Or… something else. Her voice slips. Her face glitches. Once, her shadow kept moving even when she didn’t. Another time, she showed me a drawing of me in a box with no doors.

“You’ll get it right eventually,” she said. “Or you’ll stay.”

I tried not doing anything. Just stayed in the living room, ignored her. That loop, around 6:30 p.m., she started crying without tears and whispering to something I couldn’t see. I passed out before 8:43. When I woke up, there was a note in my pocket.

Try harder.

One loop, I asked what the “best day ever” actually meant.

She looked up at me and said, “It means you’ll want to stay forever.”

I’ve given her everything. Puppets. Pancakes. New songs. I danced in the rain. I let her cut my hair once, thinking maybe it’d make her laugh. It did, for five minutes.

Then bedtime came, and she looked sad.

“Almost,” she said.

That was loop sixty-three. Or sixty-four. I’ve lost count. I haven’t aged. My bruises reset. My scars disappear. But I remember every second.

I don’t know if this post will stay up when the loop resets. If you’re reading this, and this story sounds familiar—or if you’ve heard of a girl named Ellie who gets to keep people—please, tell me what to do.

I don’t think I can make her happy.

And I think the more I fail, the more she learns how to make me stay.

—Leah

You can stop reading there and call me a liar. I wouldn’t blame you. But if you’re still here, then you either think I’m telling the truth or you’re curious enough to need what comes next. I used to think “curious enough” was the same thing as brave. Now I think it’s just the first crack where something worse gets in.

The house is at the end of a cul-de-sac with six nearly identical homes, except Ellie’s has the blue shutters. A sycamore leans over the driveway like it’s listening. Wind chimes hang under the eaves. They always sound once when I step onto the porch and then never again, no matter how hard the wind blows. Every loop, the chimes sing a single note like a doorbell for something that doesn’t use doors.

I rang the bell on loop maybe twenty and the dog barked before my finger touched the button. It’s not their dog; it’s a neighbor’s, always mid-bark as if a sound has been trapped with me. When I leave—on the loops where I manage it—the dog is still barking in the distance long after I turn the corner.

The first dozen loops, I tried to be the world’s best babysitter. I made a schedule. Crafts at 10. Lunch at 12. Quiet time at 1. Park at 3. I learned how to do one of those fishtail braids they like on YouTube and did Ellie’s hair on the couch while she watched a show about little witches going to school. She smiled at the TV. She didn’t smile at me.

“Not that one,” she murmured the third time I braided, and I felt her scalp ripple under my fingers like fish under a dock. I pulled my hands back and the hair was smooth and fine again, nothing wrong. “I like the one you do later,” she added in a singsong. Later, as in another loop. She prefers something I haven’t done yet.

I kept a notebook at first, but the book did not loop with me. I tried to hide it beneath a floorboard, in the crawlspace hatch behind the washing machine, taped under the dining table. I’d wake up at 7:58, ring the bell at 8:01—or be already stepping through because sometimes Marissa leaves the door unlocked—and the house would be clean of every version of my plans. The only thing that returns with me, every loop, is memory. And the note they can put in my pocket when they’re displeased.

Try harder.

On loop thirty, I stopped calling 911. The first operator sounded polite, faintly bored. The second sounded concerned. The third had a lot of questions about my identity. On loop nine or ten, the police car came to the cul-de-sac and idled. On loop eleven, two cars. On loop twelve, there was no car, and the houses across the street had For Sale signs I swear weren’t there before. By loop twenty, when I called, all I heard was an open line and a long, patient breath.

“Help,” I said one loop, just to say it.

“That’s what we want,” the breath replied, and then the line clicked and Ellie asked from the doorway, “Who are you talking to, Leah? It’s time for breakfast.”

By loop forty, I learned the house.

There’s a room under the stairs with a lock—the key hangs above the molding in the hall, where dust moths drift in the sunlight that shouldn’t be that still. The room smells like old rain. It’s full of boxes labeled in Marissa’s handwriting—SCHOOL, TAXES, ELLIE. The ELLIE boxes hold drawings in rivers of crayon, the kind of confident kid lines that turn circles into faces. Most are of a house with blue shutters and a girl in the window. The girl has a smile too many teeth wide. Sometimes the window has bars. Sometimes the sky has a door.

There’s a linen closet on the second floor with towels folded like hospital sheets and a space in the back that isn’t a wall. If I push hard, the space gives, and behind it there’s a crawlspace where heat collects and whispers collect and I’ve never stayed in there long because when I do the whispering starts to sound like me.

There’s a crawlspace in the attic that isn’t a crawlspace at all. It’s a narrow catwalk around the edges of the eaves, and a string runs the length of it with clothespins. I learned that on loop fifty-one, when I was out of ideas and curious enough to become someone I hated: the kind of person who snoops for fuel.

On the line are photographs. The old kind, Polaroids, with blushing whites and overfull shadows. Every other photo is of a smiling child in a kitchen I recognize. The dates are always the same date. Today’s date. Earlier years are black-and-white smiling mothers, a girl with a pageboy cut, two boys with cowlicks.

In none of the photos do the adults look into the camera. They look just past it, like something is standing where the photographer should be. In a handful, there’s a girl in the background. Blonde, big eyes, little voice if she had one. She’s always six.

Ellie.

In the newest photos, the Polaroid backs are sticky. One shows a girl about my age—dark hair, nose ring, the kind of college sweatshirt you buy before you actually get in. There’s a red thumbprint over her smile. On the lower white border, a date and a little heart drawn in ballpoint pen.

“Who is she?” I whispered on loop fifty-one, hanging by my fingertips in the attic heat.

“Someone who stayed,” said Ellie from the dark behind me. My stomach dropped. I crawled out fast enough to skin both knees. Ellie didn’t pounce. She just watched and tilted her head like a sparrow.

“She had a pretty smile,” Ellie said. “You do too.”

In the kitchen is a clock that always reads 7:58 when I arrive, 8:43 when I go. Between those times, it gets to be anything it wants—but it never gets past 8:43. I tried to set it back, to make time slow down, but the minute hand squirmed under my fingers like something alive and swung to whatever moment Ellie wanted.

“Is it broken?” I asked on loop twenty-seven.

“It’s learning,” Ellie said, buttering toast with such careful concentration that I forgave her for everything for five minutes. The toast was burned, and she scraped the black parts off and blew the crumbs into a little pile and patted the pile with the knife like she was tucking it in.

After I stopped taking her to the park, I tried other things. Board games. Forts. Card tricks. We built a castle out of sofa cushions so good the living room looked like a magazine two hundred years in the future. “It needs guests,” she said. I put dolls at tiny paper tables and drew a banner with marker that said BEST DAY EVER in a font I copied from Pinterest. She looked at the castle with that same almost-smile like maybe there’s a mosquito on her lip.

“Almost,” she said.

“What would make it perfect?” I asked.

Her head turned just slightly to the right. A light caught in her eye that wasn’t a light, not really—more like the gleam on a new tooth. “You’ll think of something.”

In other loops, I got weirder. I learned the timing of the mail truck and sprinted down the street with Ellie on my shoulders so we could wave. “He has a daughter your age,” I said, inventing, urging. “Maybe you can write her a letter.” I found stationery in the guest room desk drawer with daisies on it and gave her a pen and she wrote a letter without opening the pen cap.

“It can wait,” she said, handing me the blank page. That night I folded it and put it in my pocket and woke with a note that said Try harder.

Loop sixty I crushed my phone under my heel. Loop sixty-one I swallowed my SIM card. Loop sixty-two I called a number I’d never called in my life and my dad’s voice said “hello?” twice, sleepy, and I hung up because it felt like sin to pull people into this. Loop sixty-three Ellie painted my nails purple with glitter and said “don’t bite them” when I chewed, and then at 8:43 they were clean, and my finger tasted like something I had never tasted before and don’t have the words to name.

I need to say this: Ellie can be sweet. We feed squirrels at noon on loops I can bear to go outside. She holds my hand crossing the street. She sings a song about a dragon with a cough and coughs on purpose until she hiccups. When she laughs for real, it’s not the wrong laugh. When she cries, it is.

“I had a babysitter named June,” she told me on loop seventy-something. “She braided like you. Fishtail. She made it too tight and it hurt and then I smiled anyway.”

“You smiled?”

She nodded. “She thought it was perfect.”

“Was it?”

Ellie frowned at nothing for a long time, the way you frown when you’re trying to remember the shape of a word. “I liked the way the braid looked in the front camera,” she said. “The part where the strands go under and over. It made my head look smaller.”

I didn’t ask what that meant. Ellie laid her head in my lap and stared at the ceiling fan. “June left,” she said, as if it were the weather.

“Did you let her?”

Ellie closed her eyes. “Not yet.”

There is a line between pretending and lying, and it’s thinner every loop. The hard part is that I think Ellie believes everything she says in the moment she says it. She can hold truths like marbles in her hands and then close her fist and they’re gone and she claps like she’s proud of herself because the trick worked again.

The loop where I decided to run was hot. Agitated hot, the kind that makes the house hum like bees are living in the vents. Sweat glued my shirt to my spine. I told Ellie we’d do a backyard picnic.

“Fun,” she chirped.

I put chips, grapes, and three sandwiches in a Tupperware and an apple because I needed something with weight. I put my wallet under my shirt. I put my sneakers on without socks. I laughed at a joke she made about the ants holding a parade and I said, “Race you,” and then I grabbed her hand and we ran.

We ran. Down the lawn, past the leaning sycamore, across the cul-de-sac, between the two houses with the same fake stone mailbox. She giggled so hard she got the hiccups. We ran to the main road.

The main road was a different kind of quiet.

No cars. No birds. A plastic bag hung on a fence post and didn’t move in the wind.

“We should go back,” Ellie said, hiccuping. “You’re cheating.”

“We’re making the day bigger,” I panted. “A bigger day is a better day.”

She squinted at me. I saw the part of her that was a child assessing an offer. Then something older stepped in behind her eyes like a parent framing a scene.

“Okay,” she said. “But don’t let go.”

We walked. Blocks that used to lead to gas stations and a bright blue laundromat led to more houses that looked like copies of copies. A cat sat in a driveway and licked its paw and never stopped. I touched the cat and my fingers stayed warm like it had been alive before I got there and then had to hold the warmth in place for me.

“Left,” Ellie directed. “Now right.” I stopped listening to her and turned the other way. The sky didn’t move. We passed a light pole that had the word FOUND stapled to it in big black letters and a phone number underneath. The number was eleven digits long.

“Look,” I told Ellie because terror needs small talk, “we found something.”

“What is it?” she asked.

“Us,” I said. “We’re found.”

Her hand squeezed mine once, a test, like she was learning how much pressure makes a bruise. “You’re funny,” she said, but she wasn’t smiling.

I found the highway, or the place that wore the shape of the highway, because the sound of cars had been taken out like a laugh track. I carried Ellie down the shoulder because the asphalt was hot enough to sting through her sandals and I’m not a monster. I put her down when my arms shook. She kissed my cheek without looking and said thank you in a way that wasn’t thank you.

We climbed the embankment. The first car I saw on the overpass was empty, engine off, radio on. A song I knew played the same two bars. I leaned in through the open window and the radio sang the two bars again and then the same two and the same two until I turned it off. Ellie stood on tiptoe to twist the knob back on and it started again and I took her hand and said not this time.

“Leah,” she said, a very gentle warning.

“Why?” I said. “Why this? Why me?”

“You’re good at it.”

“At what?”

“Trying.”

The interstate was a mouth that wouldn’t open. We walked the shoulder until the heat made shimmering illusions on the horizon and then we kept walking until the shimmering was the same trick over and over and we were the only ones who weren’t allowed to leave. At some point Ellie stopped hiccuping. At some point she clapped like a game was over and said, “Nap time,” and I said, “We don’t do naps,” and she said, “You do now,” and the ground came up fast.

I woke on the porch at 7:58 with an apple seed in my molar.

Try harder.

On loop ninety, I asked Marissa to stay.

“Just ten minutes,” I said, catching her at the threshold, money already pushed into my palm. “There’s a… leak? I think? In the upstairs bathroom.”

She hesitated. Marissa is mid-thirties, Pilates-strong, the hair of a woman who pays for good hair and a mouth that shapes the word “sorry” like a party favor. “Oh god, of course,” she said. “Ellie, honey, play for a minute, I’ll be right back.”

She set her purse on the console table. I’ve seen the inside—receipts, a lipstick with the cap cracked, the very normal debris of a life lived forward. I watched her go up the stairs and then looked at Ellie. She was drawing. She’d drawn a house and a tree and a girl and a big smiling circle in the sky. The circle had too many rays for the sun.

“Marissa?” I called, loudly, and started up the stairs.

The master bedroom was crisp, magazine neat. The bathroom was the kind of bathroom that makes you feel like apologizing for your body being there. There was no leak. The air smelled faintly of lemon and something else. There was a photograph on the vanity of Ellie’s first day of kindergarten. Ellie’s hand was held by an adult’s hand in the picture, cropped at the wrist. The skin tone didn’t match Marissa’s.

“Marissa?” I said again, but she wasn’t in the bathroom.

I checked the bedroom closet—suits for a job I couldn’t guess, dresses in the colors of someone who knows what looks good on her. The closet had a wall at the back that didn’t feel like a wall. I pushed. It pushed back softly, like bread dough.

Something was written on it. Not written. Impressed. Like fingers pressing a secret into a bruise. I went closer. The impression said: THE BEST DAY EVER IS NOT YOURS.

“Leah?” Ellie called from downstairs. “Mom says she needs to go.”

I touched the impression with one finger and the wall felt skin-warm. I took a step back and then another. By the time I hit the door jamb, the impression had smoothed to an ordinary shadow.

Marissa was waiting at the foot of the stairs, purse over her shoulder, car keys like a cluster of metal grapes in her hand. “Everything okay?”

“Fine,” I lied. “False alarm.”

She laughed that light, apologetic laugh women practice to make the world go down easier. “She’s been counting down for this all week,” she said, as she always says, and kissed Ellie’s hair. Ellie did not look at her. Marissa looked at me like I could become the thing that saves her day if I tried hard enough. She said, “Text me if you need anything,” and left in a blur of scent and expensive fabric and something that wasn’t grief and wasn’t guilt but rhymed with both.

At the door, she paused, almost like she might say something else. Ellie could have said something then. Ellie could have said, Stay. She didn’t.

We listened to the car go without going. The engine noise fell away into the quiet like a rock into a lake, and the ripples didn’t reach us.

“Mom’s going to be late,” Ellie said, like she was reading off a card. “We’ll start with pancakes.”

“Okay,” I said.

“Make them smiley.”

“Okay.”

I made pancakes with blueberry eyes and a banana slice smile. Ellie bit the smile out of one with little careful bites and held the pancake face over her mouth and the blueberries lined up with her eyes and for a moment I saw a thing trying faces on like hats.

“Do you like my smile?” she asked from behind the pancake.

“Yes,” I said, which might have been the first lie of the day or the last truth.

She dropped the pancake on her plate and licked syrup from her palm with a slow, thoughtful tongue. “Not yet,” she said.

The rules evolve and they don’t. Ellie is always six. The house is always that day’s clean. The clock is always a question.

I started making a list in my head of what does change:

— The temperature of the light in the hallway (warmer when she’s excited; cooler when she’s not).

— The tightness of the shadows at noon (tighter when I’m thinking of leaving; looser when she’s not paying attention).

— The speed at which the mail slot claps (slower when I cry in the bathroom; faster when I sing in the kitchen).

— The frequency of the wind chime’s single note (one at arrival; sometimes a second if I say something true without meaning to).

— The way my own name feels in my mouth when I say it out loud (mine, and then not, and then mine again).

On loop one hundred I took Ellie’s hand at 8:42 p.m., one minute before the hush, and said, “What do you want from me?”

She blinked. The room inhaled and didn’t exhale. I felt the clock behind me tasting the next minute like a coin. Ellie smiled the toothpaste commercial smile and then it slid sideways a degree and I watched the bones of it show through.

“The best day ever,” she said. “Until you smile.”

“Me?”

She touched the corner of my mouth with a very careful finger, like she was testing the temperature of bathwater. “You always try to make me smile,” she explained gently, like she was saying two plus two. “But that’s not the day.”

“What is it then?” My mouth had become dry as paper.

“You smile,” she said. “And you mean it.”

I laughed. A bark. A scrap of an animal noise. “That’s it? That’s all?”

She tilted her head. “It’s hard.”

“Not if you—”

“Mean it,” she said, and the clock rolled into 8:43 like it knew the line and the world folded like laundry.

I woke up grinning like an idiot, forced, so hard my cheeks cramped. I held the smile until the door opened. I held it while Marissa said the words. I held it when Ellie said, “Are you ready?” I said “Best day ever” through the grit of teeth and she watched my face the way a surgeon watches a monitor.

“Not like that,” she said after an hour where I smiled while cutting strawberries and smiled while she watched a cartoon and smiled when I dropped a glass and it didn’t shatter but the sound it made went on longer than it should have. “You’ll get tired.”

“I can do it,” I told her. My lips felt like someone else’s. “I can smile for a whole day.”

“Not that one,” she repeated. And then, soft, like a promise, “I’ll wait.”

I made myself stop smiling then because I wanted to cry and didn’t want to do both things at once. “You said I have to smile,” I said. “When?”

“It’s a feeling,” she said. “You’ll know.”

“How?”

She touched my chest with her fingertip, right above my sternum. Her nail made a tiny perfect half-moon in my skin that disappeared when I blinked. “It glows,” she said.

We ate lunch on the floor because the table didn’t want us. I made grilled cheese cut into triangles and she arranged the triangles in a circle and said, “Now it’s a sun,” and I said, “The sun doesn’t have corners,” and she said, “This one does,” and she frowned down at the bread because it hadn’t respected the game. I reached out and rotated the plate, and she laughed once, surprised, a bright glass sound that made the wind chime answer.

I wanted to smile then because I wanted to be a person who could. I wanted to get it over with. I wanted to get us out.

“Almost,” she said quietly.

I started telling her stories. Not made-up ones, because she could smell the glue where I stuck the bones together. Real ones. I told her about the time my mom put the birthday candles in upside down, so the wax dripped into the cake and we had to eat around it and everyone’s lips were the color of a blue crayon from the frosting we dyed wrong. I told her about the time my biology teacher dissected a frog and fainted and I had to call the nurse while trying not to slip in the saline on the tile floor. I told her about my grandmother’s hands, the way the veins rose like rivers on a map when she kneaded dough.

She listened with her whole head. She held her breath like a jar when I said a word that mattered. She asked questions that were not the questions a child asks. “How did the room smell?” “What color was the knife?” “What did you think when you didn’t say anything?”

The loop where I said something I had never said out loud before, the light went warm enough that I thought maybe the house would melt. I told her about the time I told a boy I loved him because he said it first and my tongue couldn’t find a good way to tell the truth. She asked me his name and I said it and she repeated it once in a voice that wasn’t mine and then never again.

“Do you want to love me?” she asked, like kids ask if you want to see their new shoes.

I stopped washing the spoon and put it down. “I want to like you,” I said. “I want to be kind to you. I don’t want to stay.”

“You’ll want to,” she said, and picked up the spoon and finished washing it and dried it like she was teaching me.

That night she fell asleep in my lap while we read a book about a mouse who opens a bakery. Her breath smelled like toothpaste and the ghost of syrup. I couldn’t see the clock. I didn’t want to. I wanted to keep reading until the mouse baked a cake that had the right number of candles and the frosting was the right color and no one minded wax in the crumbs.

“Leah,” she whispered without opening her eyes. “Do you remember this part?”

“Yes.”

“Do you like it?”

“Yes.”

“Almost,” she breathed, and then the minute knocked and the house undid itself again.

The loop where I tried the basement is the loop where I stopped believing this was something any adult could fix for me.

I found the key on loop one, because Marissa stays organized like a person who feeds on compliments for being organized. The basement door is behind the pantry shelves, and you have to move the jars of canned peaches to see it. The jars are always warm. I didn’t notice that at first because I was busy, but it matters now.

The basement stairs are steeper than the house. The first step creaks the same creak three times in a row. The light switch turns the bulb on and then off and then on again whether you want it to or not. Ellie doesn’t like the basement because she doesn’t come down. She stands at the top with her toes over the edge and watches me because she believes in me enough to make me dangerous to myself.

On the shelves are boxes labeled ELLIE again—art projects, construction paper crowns, all the ordinary detritus of children plus one box that is just photographs of empty rooms. The rooms are mostly this house without people in them. In some of the photographs there are smudges that might be a camera flaw, except the smudges have fingers.

In a locked cabinet is a camcorder older than me. No tapes. But tucked way in the back is an SD card in a little plastic coffin. I risked it. I took it upstairs. I put it into the laptop I don’t own but that lives in the upstairs den because all nice houses have a den with a laptop. The card held four files. Three were corrupted. One wasn’t.

The one that wasn’t was a video of Marissa.

She sat at this same desk in a sweater I’ve never seen her wear, the kind with little daisies embroidered on the sleeves that you only wear when you’re trying to look like someone who might be forgiven. Her makeup had been applied by someone who cried and then fixed it and then pretended she hadn’t cried.

“Hi,” she said, into the camera. “If you found this, you’re either me or you’re the kind of person who opens other people’s cabinets. Either way, you’re me.”

She laughed too fast. “I’m going to try to say this without the words I used to say, because those words never did what they were supposed to. There’s a day that doesn’t stop. It didn’t start with her. I thought it did. I thought it was my fault. But my mother had a day too. And hers. And maybe you already know that because you found the pictures.”

She glanced off-camera. I wanted to see who she looked at. There was no one. Her mouth did the thing lips do when they’re listening to a sound their ears can’t hear.

“She wants a smile,” Marissa said. “Not hers. Yours. She wants you to mean it. You can’t fake it. You can’t fake this one. And you can’t get it by bribing the day. I tried. Trips. Treats. Pets.” Her laugh went cracked. “Husbands. None of them stay. Not for me.”

“Why?” I said out loud, and the video kept talking.

“She’s not a curse,” Marissa said, careful. “She’s a promise that someone broke a long time ago. I don’t know what the promise was. Maybe it was just that we’d keep each other company. Maybe it was that we’d never leave before the day ended. Maybe it was that we’d always tell the truth when we smiled.”

The video glitched and stuttered back three seconds and showed me the same words again. I watched them twice. I wanted to watch them a third time, but the file ended with the sound of a chime and Marissa’s lips moving to say “Are you ready?” like she had to practice it before she said it downstairs.

I heard the real voice from behind me. “Are you watching?”

I closed the laptop. “Yes,” I said. “I was.”

“Do you like it?”

“I don’t know.”

She came closer. She smelled like crayons and that smell under it that isn’t a smell so much as a pressure in the room. She put her chin on my shoulder and watched the black laptop screen like it was an aquarium. Our reflections looked like two girls when the screen caught us right. Then her eyes slid to mine and she said, “We can try again.”

“I’m trying,” I said.

“You will,” she agreed.

“Ellie,” I said, because I needed something and didn’t know what it was until I had to say it, “what happens to the other people? The ones who—” I didn’t know how to end the sentence. Stayed. Left. Smiled wrong.

“They’re in the pictures,” she said.

“And after the pictures?”

She put a finger on her chin and thought very hard, like she was trying to add two big numbers. “I don’t need them anymore,” she decided, and patted my cheek like I’d answered my own question.

Tonight—one of the tonights that all pretend to be the same—I took her to the park again, because the park is a loop inside a loop and the swings will let you go high enough to see over the edge if you time it right. I pushed her and she pumped her legs like someone teaching a bird to fly.

“Higher,” she said.

“You’ll kick the sky.”

“That’s funny,” she said. “Do it.”

I pushed until my palms burned. She shrieked like a real child for an instant, a ribbon unraveling, and when the swing reached its highest point I saw it—

—not a wall, not an end, but a seam. The sky folded over itself like two halves of a bedsheet. Between them was a color I can’t describe that made my teeth ache. And through that color, a smile. It was enormous and not attached to a face. It was the shape of a smile only because my brain needed a shape. It turned toward us like a sunflower and then the swing fell on the other side of the arc and the seam smoothed like a hand over linen and Ellie dragged her sneakers to slow herself and said, “Again.”

We did it again. I saw it again. The third time I saw nothing but blue. The fourth time I saw the smile wrong-way-up. The fifth time the swing chain snapped and I caught Ellie by something that wasn’t her hand and when I set her down gently she was lighter than she had any right to be, like a balloon that has forgotten what it was tethered to.

She looked up at me then and for the first time in I don’t know how many days I saw something that wasn’t a trick. It was fear.

“My turn,” I said softly, and sat on the swing beside her.

“You can’t,” she said, very fast.

“Why?”

“You won’t want to leave,” she said. The answer came too quick; it was a thing she’d been taught to say.

I pumped my legs anyway and the chains squealed and the seam opened like a mouth and I felt the color push against my teeth and tasted metal and summer and whatever the first word was before it was a word. And in that moment, in the place where the loop isn’t, I understood that the smile she wants isn’t a performance. It’s a consent.

I dragged my feet and slowed and sat still and the swing creaked and the chains sang once like a warning bell in a deep place.

“Almost,” Ellie said, tentative, as if she’d felt my thought brush hers. Her face was flushed. It made her look human in a way that hurt. “You almost did it.”

The sun slid down the wall of the day. We walked home hand in hand. The wind chime rang once. The mail slot stayed quiet; it had learned not to clap when we were making decisions. I put dinner on the table and we didn’t eat it, and at 8:30 I tucked her into bed and she held my wrist with both hands like a bracelet.

“You’ll get it right,” she whispered in the dark. “Or you’ll stay.”

“Is there a difference?” I asked before I could stop myself.

“Yes,” she said simply, as if it were obvious. “One is a gift.”

The clock waited. I waited. Ellie breathed.

I didn’t smile, because it would have been a performance and she can smell glue.

At 8:43 the house folded me back onto the porch and the wind chime sang hello. I stood there with my backpack and the fake smile I didn’t use and watched the door open on the same day wearing a new dress, and I saw something I hadn’t seen before because I hadn’t been looking up:

Above the doorframe, carved into the underside of the eave where the paint peels and you never think to look because why would you, someone had scratched a line of words. The letters were shallow, almost healed.

IT ENDS WHEN SHE SMILES.

I don’t know who she is. Ellie? Me? The seam in the sky? The woman in the video who used to be Marissa before she turned into the sort of person who apologizes to her own reflection?

It was the first new information the day had given me in a hundred versions.

I touched the carved words with my thumb and splinters bit back and I smiled before I remembered not to—because it felt like a secret and secrets are the closest thing I have to joy now.

Inside, a small voice called, “Are you ready?”

I looked at the clock. 7:58 a.m.

“Almost,” I said.

And for the first time, I meant it.

— End of Part 1 —

Part 2

The next morning (which is the same morning; which is every morning), the chime says hello and the dog barks in the distance like it has a cough stuck on a loop. I stand on the porch a breath longer and look up at the carved words again: IT ENDS WHEN SHE SMILES.

The wood has that healed-over look, like the house tried to forget the message and couldn’t. The splinters I left yesterday aren’t there. Maybe I never left them. Maybe I’m the one who carved it in a loop I don’t remember yet. Maybe the words are older than all of us.

“Are you ready?” Ellie asks from the doorway.

“No,” I say, and then, softly, “Yes.”

She steps aside so I can pass. She’s wearing the yellow dress with the snag near the hem, the snag she fingered into existence on loop twelve while I told her a story about June bugs hitting the porch light like coins in a jar. I used to think the snag was a flaw. Today it looks like proof the cloth is real.

“Rules,” I say, before the day slots into its usual grooves. “New ones.”

Ellie’s chin lifts. She loves rules, the way small monarchs love being reminded they get to make them. “Our rules?” she asks.

“Our rules,” I echo. “Three. One: no pretending. We can play, but no lying to make the game work.”

Her eyes narrow, not in anger but in carefulness. “Okay.”

“Two: no rehearsing. We don’t say things because we said them before. If we say something, it has to be because we mean it now.”

She frowns, thinking it through. “Okay.”

“Three: no keeping,” I say, and she flinches, just the tiniest twitch. “Nothing we make today is for later. Not a promise. Not a person. Not even a picture.”

A pulse of something moves through the room—fear, or hunger, or a habit turning in its sleep. Ellie’s mouth goes small. “Then it won’t be the best,” she says, almost sulky for once, almost human.

“It might,” I say. “It might be the only day that is what it says it is.”

She watches me like she’s trying to see through my eyes into the hall behind them. Then she nods once, quick, a bird pecking at a seed. “Rules,” she agrees.

We eat breakfast on the kitchen floor. I make pancakes with no faces this time. Butter and syrup and the snap of the knife against the plate where the syrup has already started to harden. She dips her finger in the syrup and paints a sticky curve on the tile and presses her palm into it and lifts it away and looks at the ghost of her hand there like a fossil.

“You can wash it,” I say, because one day it matters to me for no reason and today is a day for noticing.

“I will,” she says, but she doesn’t. The handprint gleams at the edge of my eye all morning.

I text my dad from the top of the stairs while Ellie brushes her teeth and sprays little nebulas of mint at the mirror. I’m okay, I write, and then I delete I think. He texts back a heart. It’s the kind of heart that always feels smaller than the hand that sent it. That’s not his fault; there are only so many sizes of heart in the font.

The rules change the house a little. The light in the hallway comes warmer and stays warm, a steady honey instead of the flicker of a cheap bulb about to go. The clock eats its minutes more slowly, like an animal with a full belly. The wind chime keeps its single note to itself until it has a reason.

“What now?” Ellie asks, swinging her feet from the bottom stair and kicking the banister post in that exact way kids do when they’re trying to make rhythm feel like control.

“Now we write a letter,” I say.

“To the mailman’s daughter?”

“Maybe,” I say. “Or to you. Or to me. Or to the day.”

We find paper that isn’t daisies. Printer paper, too bright, edges that could cut you if you made the wrong move. Ellie gets a purple marker and a green and a black and a blue, and I take the pen that mostly works from the junk drawer, the one with the tiny crack in the barrel that pinches your finger like a reminder.

“What do I write?” she asks.

“Something true,” I say.

She uncaps the purple and draws a circle. She draws lines from the circle for rays. She draws a face inside the circle with too many teeth on purpose. “It’s the sky,” she says.

“Okay,” I say.

She writes underneath: I DON’T KNOW HOW TO STOP.

I put the pen down because my hand is shaking and I don’t want the line that comes next to look like a lie. I write: I DON’T KNOW HOW TO START.

She takes the black. She writes: MAYBE WE DON’T HAVE TO.

I write: MAYBE WE DO.

She looks at me, surprised, like she forgot I get turns. Then she writes very small between the lines where kids stop writing because the lines are too close together: I’M SORRY ABOUT THE OTHERS.

I close my eyes. “Thank you for saying that.”

“Is it breaking a rule?” she asks, genuinely worried, like she wants me to hand her back her apology if it violates the game.

“No,” I say. “It’s the opposite.”

We fold the paper, badly, on purpose, so the crease refuses. We put it in an envelope with no address. I walk to the door and open it and hold the envelope under the mouth of the mail slot. For a second I think it will hang there in that caught place where choices wait to see if anyone is serious. Then the metal flap takes it and swallows like a throat. On the other side I hear it fall to the floor nobody stands on.

I don’t know if it goes anywhere. I don’t know if the slot opens on a real porch in a real world or if there’s a room of letters somewhere, walls rising out of paper, floor soft with confession. It doesn’t matter. What matters is we sent it.

“What now?” Ellie asks again, softer.

“Now you teach me to braid,” I say.

We sit on the couch and switch places. I kneel on the carpet and she sits behind me with her knees touching my shoulder blades, an anchor or a trap depending on who you ask. Her fingers are smaller than mine, but stronger in that exact way childhood sometimes is. She takes three strands and begins.

“Over, under,” she murmurs, not quite in rhythm, not quite not. “Over, under.”

She messes up and laughs. She messes up again and says dammit under her breath in a voice that is hers and someone else’s, and I pretend I didn’t hear, and she pretends she didn’t say it. She starts over. The third time it holds.

“It’s crooked,” she says.

“It’s straight enough,” I tell her, because the world lives on what’s straight enough.

She finishes, ties the end with an invisible ribbon (there’s no hair tie in the house when you honestly look), and pats my head like she’s knighting me. “You look like a princess,” she says.

“You look like a person,” I say, and she snorts, delighted. The sound isn’t a trick. The chime outside answers, not a single ding this time, but two, as if the metal found a second note in its throat.

We take the cushions off the couch and build a fort again, but we don’t make the magazine castle. We make a burrow, low and dark, the kind of place rabbits use when they are tired of playing rabbit. Inside, it smells like dust and coins and the moment on hot days when the first raindrop hits the sidewalk. Ellie crawls in after me with a book and a flashlight. The book is the one about the mouse baker, because of course it is. The flashlight is a cheap one with a beam that comes out like a marker line.

“Do you remember this part?” she asks, finger on a picture where the mouse burns his paw and puts it in a bowl of sugar by mistake.

“I do,” I say. “Do you like it?”

“Yes,” she says, without almost this time.

We read until the page with the cake. The cake in the book is perfect. I don’t trust it. When we get to the part with the candles, I tell the story about the candles again, about wax in the frosting. Ellie turns and looks at me very hard like she’s measuring something she can’t put in a cup.

“Will you make me a cake with wax in it?” she asks, very serious, as if she’s asking for a passport.

“Yes,” I say, and stand up, and the burrow sags and the cushion roof collapses and she shrieks with laughter as it hits her shoulder. It’s a human shriek. It’s a little too loud. I don’t shush her.

We bake like thieves. We use what the pantry gives. The flour is always full, the sugar always exactly heavy enough. The eggs crack too cleanly and fall without stringing. When I open the oven, the heat smells like the first day the school turns the heaters on. I let Ellie do the frosting with the blue we made wrong on purpose. She spreads it in stripes. It looks like someone painted the ocean and then dragged a fork through it.

“Candles,” she says, reverent.

I find a box in the drawer with the rubber bands and a screwdriver that doesn’t fit any screw and the batteries that never die. The candles are the cheap kind that gutter when you laugh. I stick them in upside down because that’s what happened then. Wax drips onto the blue. It looks like barnacles. Ellie claps, not the slow patient clap the house loves, but the savage little clap of a kid who did a thing and wants the universe to give her an A.

“Make a wish,” I say.

She doesn’t ask if she can wish for me to stay. She doesn’t ask at all. She leans over the cake—which is ours, only for now, never for later—and breathes out. The flames go, not in a whoosh, but one by one, as if each needed to hear a secret before it agreed to stop.

“What did you wish?” I ask, knowing she won’t tell me.

“For you to mean it,” she says, looking at the wax islands spreading in the blue.

“Mean what?”

“Whatever you do next.”

I cut the cake and put wax in both our slices and we eat around it and laugh grimly because it’s exactly as gross as I said it would be. When she gets a flake of wax on her tongue she spits it into her hand and holds it up to the light like something you’d find in amber. “It looks like a piece of the day,” she says.

“It is,” I say, and mean it.

We go to the park hungry from sugar. The swing hangs there like a question. I push her, but not high. She pumps once and twice and then lets her legs dangle and looks at me with a new tiredness I haven’t seen before and hope is not a bad sign.

“I don’t want to see it today,” she says.

“The seam?”

“The smile,” she corrects gently. “It makes you want the wrong thing.”

“What thing?”

“The thing that isn’t the day,” she says, as if it’s obvious. “The place beyond. The part that you can’t hold even if you say you will.”

“I won’t make you,” I tell her. “We can sit.”

So we sit at the top of the slide, which is too hot, and we burn the backs of our legs without moving because sometimes that’s what loyalty is, and we watch the neighborhood do its perfect imitation of life. Two houses away, a sprinkler ticks and ticks and doesn’t water anything. On the walking path, a man in a gray shirt runs without sweating. Ellie’s shoulder leans into mine. She is the weight a cat is when the cat trusts you enough to fall asleep.

“Will you miss me?” she asks.

“I already do,” I say, before I can stop it.

She smiles, just a little, but it’s not the kind of smile that ends things. It’s the kind that opens a window.

We go home by the long route, which is also the short route, because distance is a trick and intention is not. At the corner with the poster that says FOUND, the eleven-digit number has scuffed to ten like it is trying to learn to count properly. I take Ellie’s hand without asking and she lets me. The wind chime rings once even though we’re still half a block away, like it’s rehearsing, like even the house wants to get this right.

At 6:00, when the day usually starts to shiver, I tell her I want to call someone. She looks at me with a quick bright fear that makes me want to lie, and I don’t. “My dad,” I say. “I won’t drag him in. I just—” My throat closes. “I just want to hear a voice that isn’t ours.”

She thinks about it like a judge thinks. Then she nods once, and I call, and my dad says “hello?” and I don’t hang up. He says my name like he’s putting his hands on my shoulders. I tell him I’m okay, and he says “okay,” and then, at exactly the same moment, both of us say “I love you” and laugh because we stepped on each other’s line, and Ellie watches me and doesn’t take the phone away.

When I hang up, she says, “Does he make you smile?”

“Yes,” I say. “Even when I’m mad at him.”

She nods like this is information she can use later, not as a tool, but as grace.

At 7:00 we go under the stairs together. I move the boxes with the steadiness of someone who has decided which heavy things are worth lifting. I unlock the door to the small room and the smell of old rain breathes over us. Ellie stands in the doorway and then steps inside without touching the threshold with her toes like she used to. She puts her hands on the ELLIE boxes and then takes them away. “They’re heavy,” she says.

“They don’t have to be,” I say, and pull one down and open it and show her the drawings. House, tree, girl, sun. Bars sometimes. Door in the sky sometimes. She flips through in careful handfuls like the pictures will break if she looks too fast. At the bottom is a drawing I haven’t seen in any loop. It’s crumpled harder than paper needs to be. She smooths it with her palm.

It’s a picture of a woman and a child on a porch with a wind chime above them. The woman’s mouth is drawn as a line. The child’s mouth is drawn as a circle. Inside the circle, teeth like little tally marks.

“Did you draw this?” I ask.

She doesn’t answer. She puts it back. She takes out another. The second is a picture of the same porch, empty. The chime has two notes drawn falling from it like raindrops.

“Who smiled?” I ask.

She shakes her head and puts both pictures back and closes the box like a lid on water.

We go up to the attic. The catwalk is hot enough to make me dizzy. The photographs on the string are the same. The girl with the nose ring; the wide-mouthed kids; the mothers who never look at the camera. I take one down and hold it in the light and for a second I almost see the thing that stands where the photographer should be. It looks like the afterimage you get when you stare at a lamp and then blink.

“Don’t,” Ellie says, and I put the photograph back without asking what she meant.

On the way down, I stop at the closet in the master bedroom. The wall at the back waits like a secret that knows it will be told. I press my fingers into the skin-warm place and the impression rises to meet me: THE BEST DAY EVER IS NOT YOURS.

“Whose is it?” I ask the room.

“Mine,” Ellie says behind me, as if I’m being dense.

“Okay,” I say. “Then you decide.”

She is very still. It is the stillness of an animal holding very still so the world doesn’t notice it breathing. “Decide what?”

“What the best day is.”

We go downstairs. We wash the syrup handprint from the tile. It leaves a paler tile beneath like ghost skin. We put the wax-freckled cake into the trash and don’t hide it under napkins. We stack the blue plates in the sink and don’t run the water. We stand in the middle of the living room where the mouse bakery book lies open like a question.

“What do you want?” I ask.

She looks at the clock and then away. “For you to want to stay,” she says, rote, recitation, the script fitted to her mouth so well she doesn’t notice the seams.

“No pretending,” I remind her.

She looks at the clock again. 8:12. It has never been 8:12 for this long before. You wouldn’t think thirty-one minutes could feel like a cliff edge, but it does.

“I want…” She stops, like a record put down too fast. Her hands open and close at her sides. She hasn’t done that before. “I want to finish something,” she says.

“What thing?”

“A thing that doesn’t get taken,” she says, and the whole house seems to lean toward her to listen, the way plants lean when someone who waters them walks by.

“What can we finish?” I ask.

“Bury the box,” she says, instant, like it’s been ready, and runs under the stairs and drags out something from behind the ELLIE bins. A shoebox. The cardboard is soft with being touched too much. The lid has been taped and then untaped, taped and untaped, enough times that the tape doesn’t know whether it’s a lid or glue.

“What’s inside?” I ask.

“Things,” she says, which is the truest word children ever say.

We sit cross-legged on the floor and open it. Inside: a dried clover with four leaves. A Polaroid of a front yard at sunset with no people in it and a single silhouette in a window that might be a lamp. A purple hair tie. A button that doesn’t match any shirt I’ve ever seen. The tiniest tooth, not a baby tooth, something smaller, like it fell out of a mouth that didn’t know it had teeth. A scrap of wrapping paper with snowmen on it. The lid of a jar.

“From the peaches,” I say.

She nods. “They’re warm,” she says, and I say, “I know.”

We take the box outside. The sycamore leans in like a midwife. I get the shovel from where it always is—even in a loop, shovels know where they go—and dig under the place where the sycamore’s roots rise like knuckles. The dirt isn’t pretend-dirt today. It smells like something that was alive and turned into something else on purpose. Ellie holds the box and doesn’t complain and doesn’t drop it and doesn’t hum to fill the silence. The wind chime rings once, then once more, then holds itself very still like a person holding their breath for a surprise.

“Say it,” she tells me.

“What?”

“The words you say when people put things in the ground.”

I shake my head, because I don’t go to church and I don’t know the words and I won’t pretend. Then the right words come anyway. “Keep what we can’t,” I say, to the dirt, to the sycamore, to whatever runs the post office for prayers.

Ellie repeats, “Keep what we can’t,” and her voice cracks, the tiny crack a brook makes when it finds a rock and goes around it. I put the box in the hole and the sycamore drops one dry seed ball at our feet like it’s participating. I cover the box with earth and there’s that single holy moment where it is not in the ground yet and is not in our hands, and then it’s gone.

We go inside. I wash the dirt from her fingers in the kitchen sink and the water runs the way water runs when it’s listening to a story. I dry her hands on the dish towel that never gets wet. I take a breath and then another and then I say, “You can choose.”

“Choose what?”

“Whether I stay,” I say, and the floor tilts, and the room does not.

She stares at me like I offered her a knife and a crown at the same time. “That’s not how it works,” she says, but not like she’s sure.

“It could be.”

She is six. She is not six. She is every girl who ever stood in a doorway and said one more story to keep someone who didn’t owe her anything from leaving. She is something older than that by eons. She is only a child, and she is the person in the room who makes the weather.

She raises both hands. She puts them on my cheeks the way you hold a glass you don’t want to drop. Her fingers are clean and a little sticky from the soap we didn’t rinse properly. She leans in and puts her forehead to mine and says, very small, “I don’t know how.”

“Me either,” I whisper. “But we can try.”

We sit on the couch with the mouse book between us like a treaty. I tell her the true story I didn’t tell. I tell her about the morning I woke up in my car behind the Exxon after Leo’s funeral from a story that isn’t even mine and how the sky looked like it had been ironed and how I ate a pack of stale crackers so I wouldn’t have to think about crying. I tell her about the first kid I babysat who called me ‘Miss Lee’ because he misheard my name and how I didn’t correct him because it felt like putting on a coat I could walk around in. I tell her about stealing a piece of rain gum from the corner store when I was seven because the flavor said storm and I wanted to know what weather tasted like.

She laughs at the gum. I didn’t tell that story in any other loop. Her laugh comes and goes like a swallow. It leaves a wake of warm air. I feel it move across my face.

“You’re pretty,” she says, sudden and fierce, and I almost weep because of all the lies I’ve been told, that is one that feels like someone putting a blanket on my shoulders. “Not the kind the pictures want,” she adds gravely. “The kind the day wants.”

“What does the day want?” I ask.

She looks at the clock. 8:39. There’s a sound from inside the gears like a yawn. She looks back at me and her eyes are wet but not crying. “A present,” she says.

I think she means a gift and then I understand. “The present,” I say back.

She nods. “Stay in it,” she says. “Until it leaves.”

I take her hands. They are heavier than they should be, like they are full. “Okay,” I say. “I will.”

8:40.

The wind chime rings once.

8:41.

The dog barks, not like a cough, but like a dog.

8:42.

I do not look away from her. I do not rummage for the right expression. I do not rehearse. I do not keep. I do not plan a story to tell someone later. I do not reach into the seam. I do not bargain with anything with too many teeth.

Ellie’s mouth trembles. It wants to be a circle. It wants to be a line. It finds something else. It lifts, just on the left, the way people smile when they are remembering the exact time the cake fell lopsided and it was still cake.

The wind chime rings twice, three times, finding all its notes like it’s been waiting to practice this song for a century.

8:43 rolls toward us like a tide in a glass.

“Leah,” she whispers. “Look at me.”

I look.

She smiles.

It’s not big. It’s not a commercial. It is not full of teeth. It is a new animal that found us and sat down and put its head on our feet. It is a smile that doesn’t keep. It’s the kind you can only do once because the world is exactly this shape only now.

I don’t know I’m smiling until my face is. It hurts like blood returning to a sleeping foot. It burns and then it is warm and then it is simple. It is not the consent the seam wanted; it is not the performance the day keeps. It is a real smile because hers is.

The clock looks for its line. The minute hand hesitates, like it has to learn a new step.

8:44.

The sound it makes is not a tick. It’s an exhale.

The house breathes out.

Everything that was holding its breath does too. The dog down the street barks like he’s barked every morning for ten years and the mail slot claps and actually drops mail and someone’s sprinkler makes mud and the wind chime plays a whole phrase and then settles into being a piece of metal again.

Ellie blinks and wipes her eyes with the heel of her hand the way very small children do when they were busy doing something else and crying surprised them. “We did it,” she says, very softly, as if not to scare it.

“What happens now?” I whisper, because whispering seems right in a church and this is one for lack of anything better.

She looks toward the stairs, where the front door is a rectangle of real daylight and not the cardboard cutout we’ve lived in. “Now Mom’s late,” she says, amazed, not out of habit but because this is what late feels like when time is moving.

The door opens. It opens without rehearsing its sound.

“Ellie?” Marissa calls. Her voice cracks on the name. You don’t hear that in loop voices. “Honey? I hit every red light. I’m sorry, I—” She stops because she can see us. She puts her hand on her mouth in the way you do when you want to catch something you said before it gets out. She looks at me like she recognizes me and can’t place from where because her memory just woke up too. “Leah?”

“Hi,” I say, like you say to a person in a grocery store you didn’t expect to see, and stand up slow because I feel brand-new in a way that could break.

Marissa takes three steps into the room and stops again. Her eyes go to the clock. She laughs like someone put a hand on the back of her neck and rubbed. “Oh,” she says, in a voice that isn’t glossy. “Oh.”

Ellie slides off the couch and runs to her and stops a foot away and doesn’t jump and doesn’t cling and doesn’t make her mother’s balance have to prove anything. Marissa crouches and Ellie puts her fingers on the corner of her mother’s mouth and checks for the seam and finds none and then she puts her own mouth up and smiles a small version of the new animal and Marissa laughs again, the laugh people make when they didn’t know they could, and the house lets it land.

Marissa looks at me over Ellie’s head and for a second there is something like apology and something like awe and something like thank you for not breaking the thing I love to sharpen your own edges on. She stands and goes to the sink and turns the faucet on and the water runs. She turns it off. She looks relieved like a woman who finally got an answer on a test she’s been taking since she was six.

“I have to go,” I say, because all days end and some need you to be the one to touch the door.

“Okay,” Ellie says, and it is okay in a way it wasn’t forty minutes ago.

“Can I—” I start, and don’t have a noun for the verb. Hug? Keep? Bless? None of those are today’s words.

“Take this,” she says, and runs to the fort rubble and retrieves the mouse bakery book and holds it up. “It’s yours now,” she says, with the absolute sovereign generosity of a child giving away a treasure because she knows more will arrive.

The third rule was no keeping. I want to obey my own rules. I also want to honor the sovereignty of the giver.

“I’ll bring it back,” I say.

“You don’t have to,” she says.

“I know.” I tuck it into my backpack. The weight is exactly what a book weighs. The loop never got that right.

On the porch the sycamore throws dapple over my sneakers. The carved words above the door are gone. Not sanded, not painted over—gone, like the wood returned to itself. The wind chime is just bent aluminum and string and the particular music air makes when it passes through.

I step into sunlight that belongs to a day with a date after the one I’ve been stuck in. I take one step down, then another. Somewhere a siren sings and is actually going somewhere instead of running on a treadmill. Somewhere a woman I don’t know drops a glass and it shatters and she swears and then laughs and then sweeps.

“Leah?” Marissa says behind me. I stop because I wasn’t waiting to be called but I will answer. “Will you—” She falters. “Do you want to come back? Not today,” she adds quickly, as if saying it wrong will scare the animal away. “Another day.”

I think about the rules. No rehearsing. “Yes,” I say, if I want to. I do. Not to be the hero. Not to hold them in place. To bring a book back to a girl and sit on a couch and braid hair too tight and fix it and let the mouse bake a cake without asking it to be perfect.

“I’ll text you,” she says, and then laughs at herself because she says it like a person who thinks texting is a novelty. “Later. Not now.”

“Later,” I agree.

I walk down the path and the world does not fold me into a porch. The clock in my pocket (my phone) says 8:47 because that’s what time it is. I turn at the end of the cul-de-sac. Ellie is in the window. She doesn’t wave. She puts her palm on the glass like you do at aquariums. I put mine up and the sun finds us through the angle of old glass and that’s the picture I wish someone had the right to take: two girls not trapped in a frame.

I don’t know what kind of ending you were hoping for. Stories like to snap shut. This didn’t. It exhaled. No trumpets. No blood. No seam splitting wide to show us the engine and the teeth inside. Just a minute that finally learned what came next.

I slept that night. A real night. It was ugly, with dreams like spilled drawers—everything in the wrong place, everything mine. I woke with a line across my cheek from the pillowcase and glitter on my nails I forgot to take off that the loop didn’t wipe. On my tongue there was the taste of wax.

My phone had three texts. One from my dad with a picture of our ugly dog wearing my old sweatshirt. One from a number I didn’t have saved—Hi, it’s Marissa. We don’t have to talk about yesterday. Ellie liked you. If you want Saturday, we’ll be here. And one from an unknown with a single word: Thanks.

I went back Saturday. Of course I did. The house looked like a house that has mornings and nights. The wind chime tinkled at the wrong times because that’s what wind is for. The clock ticked too loudly because someone oiled it wrong. The jars of peaches in the pantry were room temperature and tasted like summer in syrup on a spoon. The basement smelled like boxes and not like old rain. In the attic, the photographs on the string had faded to ordinary pictures of a family who didn’t know how to pose. In the crawlspace behind the linen closet, there was dust and the kind of spider that only bites flies.

We made pancakes without faces. Ellie spilled syrup and cleaned it without being asked and then missed a spot and I cleaned it and didn’t tell her. We went to the park and the swing squealed like it needed graphite. She pumped her legs and I didn’t push, and when she reached the top she didn’t look for a seam; she looked at the boy on the next swing and said hi and he ignored her and then looked and said hi back. They compared knees. Both had scabs. She showed him how to tuck so the chain goes clack-clack. I sat on the bench and watched a sprinkler water a lawn and water a sidewalk and water the part in between and be wasteful like a blessing.

On the way home, she took my hand and then let go when she saw a squirrel because that is what hands are for on good days: reaching and releasing. At the porch, the chime sang without being asked. Over the door, smooth wood. Inside, a book on the couch. We read it. The mouse bakery ends the way it always did. He burns his paw and puts it in sugar and laughs because he is alone and it’s his job to laugh. Ellie laughed too. She looked at me to make sure I wasn’t making the day into anything other than the day. I wasn’t.

At 8:43 that night, the clock did what clocks do. It moved. It didn’t look at me first.

When I left, I looked up. No carving. My thumb still remembered splinters that never were. In the flowerbed, the dirt above the shoebox settled the way dirt settles when it keeps what you can’t. The sycamore dropped a dry ball that bounced on the walkway and rolled into the grass. Somewhere far off, a dog barked like a dog.

On the way to my car, I realized I was smiling. Not to please anyone. Not to end anything. Because I wanted to. Because the day had room for it.

I don’t know if there are other houses. I don’t know if you’re in one. If you are—if you’re standing on a porch and the chime rings once and a little voice asks if you’re ready—this is all I have:

Don’t fake it. Don’t rehearse. Don’t keep.

Bury the box.

Say the words over the hole.

Stay in the present until it leaves.

And if there’s a smile carved somewhere above your head, don’t try to pry it down to wear it. Teach each other new ones. The kind that don’t trap. The kind that end days because ending is what days are for.

It ends when she smiles.

Sometimes “she” is the child.

Sometimes it’s the day itself.

Sometimes, if you’re lucky, it’s you.

END!

News

My neighbor had the coolest name I’ve ever heard. Then he died.

Part 1 Hello my friends, I’m not really sure how to get started. But I had something exceptionally bizarre happen…

20 years ago, a child went missing. 2 months ago, I found him.

Part 1 I don’t know what I’m doing posting this to a damn internet forum, but I need to get…

I Left With $12—Two Years Later, I Bought Their House In Cash

Part 1 The scent of lilies and stale grief clung to me like a shroud. I stood in front of…

Mom Sold My Childhood Home For $7 And Lied About It

Part 1 The email hit my inbox like a punch to the gut. Not the email itself, but the attachments—screenshots…

My Mom Sent 76 Invites—Guess Who She “Forgot”?

Part 1 of 2 The email wasn’t even addressed to me. It arrived like a digital slap—a sloppy forward from…

Left Out of the $75K Inheritance “Because I Didn’t Marry Well”—Until My Name Was Read Last

Part 1 The cream‑colored envelope felt heavier than paper ought to. It wasn’t just the cardstock—my family preferred thick things,…

End of content

No more pages to load