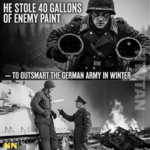

He STOLE Gallons of Enemy Paint To Make 15 Sherman Tanks Disappear

They were surrounded by snow, steel, and silence.

It was the kind of cold that didn’t just sting your skin—it hunted its way into your bones and set up camp there. The sky over Belgium in late December 1944 was a low, iron lid, and the snow on the ground reflected what little light there was, turning the whole landscape into a blinding, colorless desert.

And right in the middle of that endless white sat fifteen Sherman tanks that might as well have been screaming their presence to the world.

They were olive green and caked with frozen mud, dark, hulking shapes against the glowing snowfields. Each turret, each barrel, each track was a black slash in a white painting—perfect targets for anyone with a scope and a grudge.

Sergeant Walter “Walt” Henderson stood with his gloved hands jammed into the pockets of his field jacket, watching his tanks glow under the moonlight like wounded animals. Steam puffed from his mouth with every breath, curling upward and vanishing into the night.

“Jesus,” he muttered under his breath. “Might as well nail up a sign that says ‘Bomb Here.’”

Behind him, the small Belgian village huddled against the wind, roofs drooping under snow, windows dark. Somewhere a dog barked once and went quiet. Somewhere else a child cried, the sound thin and exhausted.

It was winter on the Western Front. The Battle of the Bulge was grinding on, and the Third Armored Division was stretched thin across Belgium and northern France, pushing the Germans back yard by frozen yard. The front line was a shifting smear on the map, always too close, always too uncertain.

Walt wasn’t a tanker, not in the way the guys in the turrets were. His battlefield wasn’t the inside of a Sherman, it was underneath it.

He was a tank mechanic, part of a maintenance detachment that followed the division like a mobile hospital, patching up wounded steel so it could go back out to kill and be killed. He was known for two things: a temper that flared faster than gasoline, and improvisations that shouldn’t have worked but somehow always did.

He had grown up in a hot, grease-stinking garage in Ohio, under the watchful gaze of a father who judged a man not by his words but by whether or not he could get a stubborn engine to turn over. Walt’s childhood had been an orchestra of tools: the ratcheting click of wrenches, the hollow thud of hammers on stuck bolts, the hiss of steam and cursing. He’d learned early that you never had the exact part you wanted, that the catalog was a distant fairy tale and you lived in the land of whatever the hell you had lying around.

Now, thousands of miles from that garage, he was staring at fifteen tanks that needed something nobody had thought to supply.

Camouflage.

The temperature had dropped as the battalion halted outside the village, the mercury plunging down toward fifteen below. Engines froze if you let them sit too long. Oil turned sluggish and mean. Men wrapped themselves in whatever they could find: extra blankets, German scarves, burlap sacks, even newspapers tucked into their jackets.

The tanks, though, didn’t care about comfort. They cared about survival.

And right now, they looked like neon signs on fresh snow.

Behind Walt, boots crunched on the frozen ground. Captain Edward Marshall, his commanding officer, walked up with his collar turned up against the wind, a clipboard under his arm and a cigarette burning low in his fingers.

“Sergeant Henderson,” Marshall said, his breath ghosting in front of him. “You get those track problems sorted on Baker Platoon?”

“Yes, sir,” Walt said. “Rust knocked out, links tightened, idlers adjusted. They’re good to roll if the engines don’t seize up.”

“Engines seize, that’s your problem,” Marshall said, squinting toward the tanks. “Enemy mortars start walking toward us, that’s mine.”

He fell silent, staring at the row of Shermans. They were lined up along the edge of the village, hulls angled toward the fields, ready to push out as soon as orders came. Their dark shapes were obvious even from where they stood.

“Scouts say Jerry’s got spotters on those tree lines,” Marshall said. “If Luftwaffe boys get through the clouds or their arty gets good coordinates…” He took a drag from his cigarette, letting the end burn bright in the gloom. “They’ll be zeroed in on those babies in no time. We’ll be a damn shooting gallery.”

“Sir, they can see us clear as day,” Walt said. “Or clear as night, I guess.”

“Headquarters says dig in what you can,” Marshall replied. “Throw snow over anything that doesn’t move and pray we get fogged in by morning.”

He said it with the weary resignation of a man who’d gotten too many orders that weren’t quite enough.

Walt kept staring at the tanks. He imagined German artillery crews somewhere out there, hunched over maps and range tables, rubbing gloved hands together as they dialed in on these perfect little green targets on the white board.

“Begging your pardon, sir,” Walt said slowly, “but digging in a Sherman isn’t exactly quick work. We don’t have the equipment to bury fifteen of ‘em overnight. Even if we did, those hulls are still going to show dark through the snow. They look like… like big green pimples on a white face.”

“You got a better idea?” Marshall asked. There wasn’t challenge in his voice, just tired curiosity. He knew Walt. He knew that when that particular furrow appeared between the mechanic’s brows, something strange was about to happen.

Walt didn’t answer right away.

Instead, he let his gaze drift past the tanks, across the empty field, to the broken line of trees in the distance. Beyond those trees, somewhere in the darkness, was a half-ruined German supply depot they had passed that afternoon. The engineers had slapped a big chalk mark on one of its walls: CLEARED.

He remembered something else, too. A flash of white amid the rubble. Stacked metal drums, their labels catching his eye for a second as the jeep rolled past.

Weiss Farbe. Winter Tarnung.

White paint. Winter camouflage. For German tanks.

The memory clicked into place with an almost audible snap.

If the Germans could paint their tanks white so they wouldn’t be seen in snow… why couldn’t the Americans?

He looked back at the tanks. The olive drab hulls glowed dully in the moonlight like sleeping beasts.

Paint them, his mind whispered. Turn ‘em white. Make ‘em vanish.

It was a stupid idea. It was reckless. It was unauthorized. It was exactly the kind of thinking that got a sergeant chewed out.

It was also exactly the kind of thinking that might save fifteen tanks—and the crews inside them—from being torn apart by shrapnel before they ever fired a shot.

“Sergeant,” Marshall said, exhaling smoke, “I asked you a question.”

“Yes, sir,” Walt said. Then: “Sir… what if they couldn’t see them?”

“Who?” Marshall frowned. “The Germans?”

“Yes, sir.”

“How in God’s name are they not going to see fifteen tanks sitting in a field?”

Walt took a breath. He felt the cold burn in his lungs.

“If the Germans can paint tanks, so can we,” he said. “I think I know where there’s some… paint we can borrow.”

“Oh, hell,” Marshall muttered. He turned to face Walt fully. “What are you suggesting?”

“German depot, couple miles back along the road,” Walt said. “One the engineers marked cleared. Saw some drums there. White paint. It’s what they use on their own armor on the Eastern Front, far as I’ve heard.”

“So you want to waltz back toward the enemy, into a bombed-out Kraut dump, in the dark, and steal their paint?” Marshall asked. “To paint my tanks?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Not regulation,” Marshall said flatly.

“No, sir.”

“Not authorized.”

“No, sir.”

Marshall stared at him for a long moment. Walt could see the wheels turning behind the captain’s eyes. Regulations were one thing. Getting his men killed because he’d followed them too literally was another.

“Can you do it?” Marshall asked quietly. “Get there and back without drawing fire? Without getting captured?”

Walt shrugged one shoulder.

“If we’re lucky,” he said. “And if we’re not, they weren’t going to give us medals for sitting here and dying pretty, anyway.”

Marshall’s mouth twitched. In another life, it might have been a smile.

“You take anyone with you?”

“Couple of my boys,” Walt said. “McCloskey and Ruiz. They’re good in a jeep, quiet when they have to be.”

“Fine,” Marshall said finally. “You take a jeep. No lights. You avoid any village or road that looks too quiet, because it won’t be. You load what you can, and you get the hell back here before first light. You get yourself killed, I swear to God I’ll resurrect you just so I can court-martial your ass.”

“Yes, sir,” Walt said, and despite the threat, there was a warmth in his chest he hadn’t felt in weeks. Someone was trusting him to be crazy again.

“And Henderson,” Marshall added as he turned away, “if this works… I never heard about that depot. I never authorized a damn thing. Understood?”

“Crystal clear, sir,” Walt said.

Later, when the snow had thickened and midnight was creeping over the battlefield, a lone jeep rumbled away from the American lines, its headlights blacked out, its engine a low growl under the sound of the wind.

Walt sat behind the wheel, squinting through the narrow slit in the canvas cover. Beside him, Private Luis Ruiz hunched into his jacket, breath a steady fog. In the back, Private Joe McCloskey cradled his rifle, eyes constantly sweeping the white-blanketed countryside.

“This is insane, Sarge,” McCloskey said, his voice low. “Everybody else is freezing their asses off in foxholes, and we’re going shopping for paint.”

“You want to go back?” Walt asked.

“Didn’t say that,” McCloskey muttered. “Just saying, if I get killed stealing home décor from the Wehrmacht, I’m gonna be real pissed off.”

Ruiz chuckled under his breath.

“My mamá always said I’d die doing something stupid,” he said. “Guess this qualifies.”

“We’re not dying,” Walt said. “Not tonight. Not for paint. We’re just… borrowing some German vanity products, is all. They like their tanks looking pretty.”

The jeep bounced over a rut, the suspension groaning.

The night was too quiet. No artillery, no machine gun bursts, just the distant murmur of war like a storm on the horizon. They passed the blackened skeleton of a farmhouse, its roof collapsed, its fields now just white sheets hiding burned earth and debris. A single chimney stood like a finger pointing accusingly at the sky.

Walt’s hands were tight on the wheel. Every shadow looked like a patrol. Every cluster of trees could hide a MG-42 waiting to chew them into rags. He tried to focus on the memory of the depot, replaying the afternoon’s drive like a film in his head.

“About half a klick past that crossroads where the sign was shot to hell,” he murmured. “On the left, behind those busted rail cars.”

“What if the engineers were wrong?” Ruiz asked. “What if it’s not cleared?”

“Then we look real surprised and die with empty paint cans,” Walt said.

They reached the crossroads. The road sign was still there, its metal pitted and twisted, the names of villages riddled with bullet holes. Walt turned left, following tracks half-buried in snow.

“There,” he said quietly. “See those boxcars?”

The depot was a smear of black against the white, hunched low and broken. A section of wall had collapsed inward, spilling bricks into the snow. A twisted metal gate lay on its side like a dropped toy. The boxcars sat on rusted rails, their doors open, their insides dark.

Walt killed the engine.

Silence rushed in, thick and total. The ticking of the cooling motor sounded loud as gunshots.

“Ruiz, with me,” Walt whispered. “McCloskey, you stay with the jeep. If you see anything moves, anyone at all, you honk once and drive toward home. Don’t wait for us.”

“Like hell I will,” McCloskey said.

“Don’t be a hero,” Walt said. “We’re already doing something stupid. No need to make it suicidal.”

Ruiz and Walt stepped out into the snow. It squeaked under their boots. Their breath seemed offensively loud.

They kept low as they approached the depot, hugging the shadows of the boxcars. The air smelled faintly of oil and old smoke.

The engineers’ chalk scrawl was still visible on a section of intact wall: CLEARED. Somebody had drawn a crude smiley face beside it, as if to lighten the fact that “cleared” was a relative term in war—it just meant nobody had found a mine there yet.

“Here we go,” Ruiz murmured, peering into the nearest doorway. “Empty. Empty. Busted crates… Hello, what’s this?”

They stepped into the broken building. The roof above them was patchy, letting in bands of moonlight that painted pale stripes across the floor. Snow had drifted through the holes in soft piles.

And there, against the far wall, stood the metal drums Walt had seen. A whole row of them, squat and utilitarian, stenciled with black letters in German.

Weiss Farbe. Winter Tarnung.

White paint. Winter camouflage.

Walt let out a short, disbelieving laugh.

“Well, I’ll be damned,” he said. “They left us the good stuff.”

Ruiz walked up and rapped his knuckles against one drum. It rang solid and full.

“You sure this ain’t some kind of poison?” he asked.

“Only poison to the German war effort,” Walt said. “Pop the lid.”

They pried one open with the butt of a wrench. Inside, thick white liquid gleamed in the dim light, smooth as cream.

Walt dipped a gloved finger in and spread it on the inside of the lid. It shone pale and matte.

“Looks like paint. Smells like paint,” he said. “We’re in business.”

They grabbed every container they could find—old fuel cans, battered buckets, even a couple of discarded mess tins—and started filling them. The paint glugged slowly, resisting the cold. It splashed onto their gloves, their sleeves, their boots, turning them into messy ghosts.

“How much you want?” Ruiz asked, grunting as he hefted a brimming can.

“Everything that’ll fit on the jeep,” Walt said. “If we’re going to risk our asses, we might as well steal enough to make it worth the trip.”

Milk runs, his father used to say. If you’re gonna run milk, you don’t come back with half a bottle.

By the time they were done, they had about forty gallons of the stuff. They loaded the cans into the back of the jeep, wedging them in tight so they wouldn’t slosh too much.

McCloskey eyed the cargo skeptically.

“That’s a lot of white,” he muttered. “You gonna start painting the whole damn army, Sarge?”

“Just the important parts,” Walt said. “Like the big steel things that keep getting shot at.”

They climbed back into the jeep. Walt took one last look at the depot, at the fading German words on the drums.

“Thanks for the donation, fellas,” he whispered to ghosts who weren’t there. “We’ll put it to good use.”

The drive back felt even longer.

Every minute they were out there was another minute for some German patrol to stumble across them, another minute for some artillery observer to decide to put a few random shells onto the roads. But the night stayed quiet. The world remained a cold, breathless place where the only sound was their engine and the crunch of tires on hard snow.

When they finally rolled back into the American lines, the sentries stared at the white-spattered jeep, then at the dripping cans in the back.

“What in the holy hell is that?” one of them asked.

“Art supplies,” Walt said, swinging down from the driver’s seat. “We’re gonna paint ourselves a miracle.”

Dawn came slow and gray, the sky a solid slab that promised more snow.

The men of the maintenance detachment woke to the sound of shouted orders and clanging metal. They shuffled out into the cold, rubbing sleep from their eyes, and froze when they saw Walt standing next to the nearest Sherman tank with a brush in his hand and white paint streaked across his face like war paint.

He slapped a thick stripe across the side of the tank’s hull. The olive drab disappeared beneath it, replaced by a messy, uneven patch of white that shone like fresh snow.

“Sergeant, have you completely lost your mind?” Lieutenant Harris, the platoon leader, demanded, trudging up with his scarf pulled over his nose.

“Not yet, sir,” Walt said, grabbing another brush and tossing it to Ruiz. “But give it time.”

“We can’t just… repaint government property,” Harris sputtered. “There are procedures. Orders. Chain of command.”

“Sir, with all due respect,” Walt said, “if we wait for paperwork, Jerry’s gonna have plenty of time to file his own paperwork on us. Name, rank, serial number, and next of kin.”

He slapped another streak of paint. The white blob spread, connecting to the first.

“This is unauthorized modification of military equipment,” Harris insisted. “At the very least, you’ll be…”

He trailed off.

Snow had started to fall again, soft flakes drifting down around them. Some landed on the fresh paint, melting and blending, turning the surface into a mottled patch of white and gray that, from just a few steps back, looked disturbingly like the snowbank behind it.

Harris frowned. He took a few steps away, squinted, then took a few more.

At thirty yards, the tank’s shape broke up. The hard lines blurred. The turret, half-painted, still stood out, but the section of hull Walt had been working on was already harder to pick out against the ground.

At fifty yards, in the morning haze, it looked less like a tank and more like a chunk of snowdrift.

“Son of a bitch,” Harris muttered.

“Permission to keep painting, sir?” Walt called.

Harris didn’t answer right away. He looked from the tank to the line of dark Shermans behind it, then back to the open fields, where any German with a pair of binoculars could easily count every vehicle they had.

“Get me Captain Marshall,” he said to a nearby private. “Now.”

Ten minutes later, Marshall stood beside him, hands on his hips, eyes narrowed. Walt’s brush didn’t stop moving.

“I should write you up,” Marshall said without preamble. “You know that, Sergeant.”

“Yes, sir,” Walt said. “You absolutely should.”

“And yet…” Marshall squinted at the tank, then at the snow, then back again. A slow smile bent his mouth. “…that is one ugly son of a gun.”

“Sir?” Walt asked.

“Ugly,” Marshall repeated. “And beautiful. In a damn ugly way.”

From a hundred yards out, the camouflage was startling.

Walt had ordered his men to go wild: not just solid white, but big splotches and streaks, uneven patterns that mimicked the way snow piled up on natural ground and trees. They painted over the olive drab in broad strokes, leaving shadows and patches where grime still clung. They dabbed around the gun barrels, the turrets, the hatches. They splashed paint over tracks and road wheels, over stowage and spare track links strapped to the hulls.

When the snow came down harder, it dusted the fresh paint, softening the brush marks, filling in the gaps. The hard, human-made lines of the tanks dissolved into something that the eye, at a distance, had trouble reading.

From the edge of the village, Marshall, Harris, and a handful of officers and NCOs stood with binoculars, scanning the field.

“I count eleven,” Harris said, chewing his lip.

“There are fifteen,” Marshall said. “You’re missing four.”

“You sure?” Harris asked.

Marshall passed him a different set of glasses.

“Look again,” he said.

Harris swept the field slowly. The snow made his eyes ache. He found one, two, three… lost them… found another, half-hidden by a hedge.

“Goddamn,” he whispered. “They’re right there.”

The tanks hadn’t moved. But in the space of a few hours and forty stolen gallons of German paint, they might as well have driven off the map.

Word spread through the battalion faster than frost.

Men from other companies wandered over to stare at the ghostly white Shermans, shaking their heads, laughing, clapping Walt on the back.

“You’re crazy, Henderson,” one tanker said, his breath fogging. “But if this keeps me from getting blown to hell, I’ll buy you a drink when this is over.”

“I’ll hold you to that,” Walt said, straightening up from his crouch to stretch his aching back. His fingers were numb beneath his paint-sodden gloves.

By afternoon, all fifteen tanks gleamed pale and strange in the snowy field, hulks of steel turned into great white beasts crouching in the drifts.

The Germans never saw it coming.

Later that day, as the gray sky deepened and the wind picked up, the first artillery shells began to fall.

The sound started as a distant rumble, then rose to a shriek as the shells descended. They landed hundreds of yards short of the village, geysers of earth and snow punching up from the ground.

“Down!” someone yelled. Men hit the dirt, ducked behind walls, dived into foxholes.

Walt dropped into a shallow ditch, covering his head as the barrage continued. Shell after shell impacted, some closer, some farther, but all of them surprisingly off-target.

In the village, a few chimneys crumbled. A cart overturned. A shed took a direct hit and exploded into splinters. But the tanks, sitting in their stillness, remained untouched.

In a small stone farmhouse a few kilometers away, a German artillery officer cursed as he studied the reports coming in by wired phone.

“The Americans were there,” a forward observer insisted. “I saw the tanks. Fifteen, maybe more. They were lined up along the edge of the village, near the orchard.”

“And now?” the officer snapped.

“And now…” The observer hesitated. “…now I do not see them. Perhaps they moved overnight. Their tracks are covered by snow. I see only… white.”

The officer gritted his teeth.

“Then we adjust fire and hit the village,” he growled. “If the tanks moved, we will catch them when they return. Keep watching.”

He did not know that he was watching exactly what he thought he was not: tanks that had not moved at all.

Not long after the barrage ended, a single German reconnaissance plane sliced through the low clouds, its engine a faint drone above the wind.

In the belly of the aircraft, a young Luftwaffe pilot peered through his camera and his eyes, scanning the patchwork of fields and villages below for any sign of armored columns.

He saw dark roads, pale fields, black scars where earlier battles had burned the ground. He saw the village, its roofs white with snow. He saw lines of foxholes like stitched scars.

He did not see fifteen Sherman tanks.

“Area clear of armor,” he reported when he returned. “The Americans must have pulled back. Only infantry positions remain.”

Far below, the “pulled back” Shermans sat in silence, their crews huddled inside, engines off to conserve fuel and prevent heat signatures. The tanks were waiting. Hiding in plain sight.

For three days, the tanks held their positions.

Snow fell, melted, froze again. The white paint took it all, growing mottled and stained, the camouflage becoming even more convincing as nature added its own brushstrokes on top of the human ones.

Inside the tanks, men played cards with gloved fingers, swapped stories, shivered, and waited for the order to move. They knew how vulnerable a tank could be on the open field. They had all seen what German artillery and anti-tank guns could do to steel.

They also knew what their tanks looked like to the naked eye from outside now. Ruiz had walked out to a distant hedgerow with a pair of binoculars and reported back, almost laughing, that he couldn’t find his own vehicle for a good thirty seconds.

“You realize,” one of the tank commanders said, “that we owe our hides to a guy who stole art supplies from the enemy.”

“Mechanic,” another corrected. “Not artist.”

“Tell that to the Germans,” the commander said. “They’re the ones looking at a blank canvas.”

On the third morning, as the front stabilized and new orders came down, Captain Marshall walked the line of camouflaged tanks with his hands clasped behind his back.

He stopped when he reached Walt, who was sitting on an overturned crate, scraping frozen paint out of a brush with a knife.

“Henderson,” Marshall said.

“Sir.”

“Division headquarters heard about your…” Marshall’s mouth twitched. “…little project.”

Walt felt his stomach sink.

“Sir, I—”

“Relax, Sergeant,” Marshall said. “If they wanted your ass, they’d have sent MPs, not a memo.”

He pulled a folded paper from his coat and handed it to Walt.

“‘Sergeant Henderson applied tactical camouflage under combat conditions,’” Marshall read. “‘Result: zero losses.’”

Walt blinked.

“That’s it?” he asked. “That’s the report?”

“That’s the report,” Marshall said. “They asked me if I’d authorized it. I said you’d interpreted the orders to dig in and reduce visibility to the best of your ability, given available materials. I used a lot of words like ‘initiative’ and ‘field expediency.’ Generals eat that stuff up when it works.”

“No punishment?” Walt asked.

“No punishment,” Marshall said. “No medals, either. We don’t give out Bronze Stars for creative painting, apparently. Just quiet respect and a story that’ll get taller every time someone tells it.”

“That suits me fine, sir,” Walt said, though there was a small sting beneath the relief. Part of him had hoped someone, somewhere, might put a little black ribbon on a piece of paper and say: You did good.

But then he thought of the artillery shells landing short. He thought of the tankers laughing nervously in their turrets, alive. He thought of fifteen hulks of steel still ready to fight instead of twisted wrecks smoking in the snow.

Yeah, he thought. That’s a pretty good medal on its own.

“Word’s already spreading,” Marshall said. “Other crews are mixing whitewash with mud and lime, slapping it on anything that rolls. There’s talk of making it standard practice any time we’re in snow country. You might have started something here, Henderson.”

“It’s German paint,” Walt said. “Figured it’s about time it did something useful.”

Marshall chuckled.

“Sometimes I think we’re gonna win this damn war,” he said, “not because we have more tanks or more men, but because we have more idiots willing to break the rules at the right moment.”

He walked away, leaving Walt sitting with the memo in his hands. The words on the paper were plain, almost boring.

Applied tactical camouflage under combat conditions. Result: zero losses.

He folded it carefully and tucked it into his breast pocket, next to a crumpled photograph of his parents standing in front of their garage.

The war went on.

The tanks rolled forward when the weather cleared, emerging from the snow like phantoms, white ghosts rumbling toward the German lines. On more than one occasion, German infantrymen found themselves scrambling to load Panzerfausts only to realize that what they’d thought was an empty field had sprouted steel monsters thirty seconds too late.

Some of those Shermans were lost in later fighting. No amount of paint could stop an 88mm shell or a properly laid mine. Men died, as they always did, in explosions and fire and quiet, empty moments when the bullet that killed them barely made a sound.

But in that frozen field outside a nameless Belgian village, for those three days when they were most vulnerable, fifteen tanks and their crews had been given a chance.

After the war, historians would look back at those makeshift ghost tanks and call it one of the earliest examples of improvised battlefield camouflage in Western Europe. They’d note how quickly the practice spread, how photos from the Ardennes and beyond showed American tanks in messy winter coats, white over green, the result of men with no official orders deciding to paint their own salvation.

They’d write papers and give lectures. They’d talk about “innovation under fire” and “bottom-up tactical adaptation.” They’d use phrases like that and nod at each other in conference halls.

Walt never read any of those.

He had a different life to get back to.

After the war, he returned home to Ohio to find the garage where he’d grown up still standing, the sign over the door a little more faded, the hinges a little more stubborn. His father’s hair had gone white, his hands slower, but the tools were all in their places, hanging on the pegboard like old friends.

“You bring anything back?” his father asked him one night, sitting on the tailgate of a pickup as the sun sank behind the trees.

“A bad back, a few scars, and a healthy hatred of snow,” Walt said.

“That all?” his father asked.

Walt hesitated.

“And one good story,” he said. “About some paint.”

His father raised an eyebrow.

“Paint?” he asked.

“Yeah,” Walt said. “I’ll tell you sometime.”

He didn’t tell him right away. The story felt heavy, like something you carried in your pocket for a while before you decided to show it to anyone.

Instead, he went back to work.

He opened a small auto repair shop on the edge of town. The sign on the front read HENDERSON & SON for a while, and when his father passed, he left it that way. People brought him their broken cars and trucks, their stalled engines and bent frames. He fixed them with the same stubborn determination he’d used on seized Sherman transmissions and busted road wheels.

Sometimes, on winter mornings when the snow lay thick on the streets and the world was quiet, he’d open the shop door and watch as cars eased along the white roads, their dark bodies stark against the snow. He’d catch himself thinking: If I had a few gallons of paint, I could make that Buick disappear.

Years passed. The war receded into black-and-white photographs and anniversary newspaper articles. Young men grew into old men, medals tarnished in drawer bottoms, uniforms smelling faintly of mothballs.

One day, a teenager with a crew cut and restless hands came into the shop looking for a part-time job.

“You Henderson?” the kid asked.

“That’s what it says on the sign,” Walt replied.

“They say you were a mechanic in the war,” the kid said. “Over in Europe. Third Armored, right?”

“Who’s ‘they’?” Walt asked.

“My granddad,” the kid said. “He was a tanker. Says there was this story going around, about some sergeant who stole German paint and made a whole column of tanks vanish in the snow. Says nobody ever quite believed it, but he swears it’s true. That you?”

Walt paused.

Outside, snow was falling, soft and lazy, settling on the hood of a car parked at the curb. For a moment, he saw not the street but a Belgian field, not the car but a Sherman with a long, impatient barrel.

“Sometimes you just gotta paint your own tank,” he said.

“What’s that mean?” the kid asked.

Walt smiled, a tired, amused thing.

“Means if you sit around waiting for someone in an office to tell you how to save your own skin, you’re liable to be dead by the time the memo arrives,” he said. “Means when the problem’s staring you in the face, you use what you got, even if it ain’t in the manual.”

He picked up a rag, wiped his hands.

“Means,” he added, “that story your granddad told you? Yeah. It’s true.”

The kid’s eyes widened.

“No kidding?” he breathed.

“No kidding,” Walt said. “You want the long version, you can hear it while you’re sweeping the floor. You did say you wanted a job, right?”

“Uh, yes, sir,” the kid said quickly.

“Good,” Walt said. “Grab that broom. And maybe grab a notepad, too. Might be some things worth remembering.”

As the years went on, small-town reporters occasionally wandered into Walt’s shop looking for “local hero” stories to run on Veterans Day. They’d ask him about the war, about battles and medals and near-misses.

He’d shrug and talk about keeping engines running in the cold, about how mud got into everything, about how the smell of burnt oil never really left your nose.

If they pushed, he might, just might, tell them a piece of the paint story. How ugly those white tanks were. How beautiful that ugliness became when the shells started falling somewhere else.

“Did you get a medal for it?” one young reporter asked him once, her pen poised over her notebook.

“No,” he said.

“Why not?” she demanded, visibly offended on his behalf. “You saved fifteen tanks.”

“Because I broke the rules,” he said. “And because the men who didn’t make it home deserved the medals more.”

He looked past her, through the shop window, at the snow drifting lazily down.

“Besides,” he added, “I got what mattered.”

“What’s that?” she asked.

He tapped his chest, right over the place where, long ago, he’d kept a folded memo and a faded photograph.

“Zero losses,” he said. “That was enough.”

The historian who finally wrote the article years later about improvised winter camouflage on the Western Front included his story under a small subheading: “The Henderson Incident.”

He mentioned the forty stolen gallons of German Weis sFarbe Winter Tarnung, the fifteen Sherman tanks, the artillery shells falling hundreds of yards off target. He quoted from the memo: applied tactical camouflage under combat conditions. Result: zero losses.

He wrote all that, but he didn’t capture the way the paint smelled in the cold air, or how the brush handles felt in numb fingers, or how a man’s breath caught in his throat when he realized his tank had vanished from sight.

Those parts lived only in the memories of the men who had been there—and in the quiet retellings in garages and living rooms and VFW halls.

Sometimes, late at night, when the snow piled up against the shop door and the world outside was dark and still, Walt would sit alone at his workbench, a mug of coffee cooling beside him.

He’d take a small, battered notebook from the drawer. Taped to the inside cover was the old memo from Captain Marshall, now yellowed and fragile. Beneath it, in shaky handwriting, he’d once added his own note:

Forty gallons of enemy paint. Fifteen tanks. Three days. Zero losses. Worth the trouble.

He’d trace the words with a fingertip, then close the notebook and slide it back into the drawer.

He didn’t think of himself as a hero. Heroes, in his mind, were the men who never got to complain about their bad knees or their aching backs. The ones who didn’t get to open garages in Ohio or tell stories to wide-eyed kids.

He thought of himself as a mechanic who, once upon a winter, had looked at a problem and seen something stupid he could try.

The genius hadn’t been in the paint. It had been in the willingness to pick up a brush without waiting for permission.

Years later, when someone asked him what he’d learned from the war, he answered without hesitation.

“That sometimes the difference between living and dying,” he said, “is having the guts to break the right rule at the right time. And having a good steady hand with a paintbrush doesn’t hurt, either.”

He STOLE gallons of enemy paint, but what he really stole was time: days in which shells missed, planes passed overhead blind, and fifteen tanks waited for the moment they could roll out of hiding and do their job.

In a world of orders and red tape, where every piece of equipment had a serial number and every action a form, one stubborn sergeant with a crazy idea proved something simple and enduring:

Sometimes, if you want to save your tank, you don’t wait for someone else to cover you.

Sometimes, you just paint your own tank.

News

Karen threw hot coffee at my brother-in-law for the window seat not knowing I own 62 airports

Karen threw hot coffee at my brother-in-law for the window seat not knowing I own 62 airports Part 1…

Karen Told Me I Couldn’t Have a Pool — So I Built One That Broke the HOA!

Karen Told Me I Couldn’t Have a Pool — So I Built One That Broke the HOA Part 1…

HOA Karen B*CTH steals kids medical equipment gets hit with grand larceny charges and lands in jail!

HOA Karen B*CTH steals kids medical equipment gets hit with grand larceny charges and lands in jail! Part 1…

I saw my daughter in the metro with her child and asked her: ‘Why aren’t you driving the car….

I saw my daughter in the metro with her child and asked her: “Why aren’t you driving the car I…

My Daughter woke me before sunrise and said, “Make some coffee and set the table.”

My Daughter Woke Me Before Sunrise And Said, “Make Some Coffee And Set The Table.” Part 1 At my…

MY HUSBAND GOT HIS ASSISTANT PREGNANT, THEN EXPECTED ME TO STAY QUIET AND PLAY HAPPY FAMILY. HE S…

My husband got his assistant pregnant, then expected me to stay quiet and play happy family. He sneered, “You’ll accept…

End of content

No more pages to load