German Pilots Laughed When They First Saw The Me 262 Jet — Then Realized It Was 3 Years Late

January 1945.

The telephone rang in the silence of the hunting lodge.

Snow lay heavy on the fir trees of the Harz Mountains, swallowing sound, turning the world outside into a gray, muffled dream. Inside, the fire in the stone hearth had burned down to embers. The only light came from a single lamp on the desk where Major General Adolf Galland sat, a book open but unread in front of him.

He stared at the ringing telephone as if it were an enemy.

For months, that phone had brought only bad news. Reports of airfields lost. Squadrons shattered. Cities burned. Pilots’ names read like obituaries. He had stopped asking how many. The numbers were always worse than the week before.

The bell rang again, shrill and insistent.

Galland set the book aside, feeling the familiar weight of his broken career like a stone in his chest. Until recently, he had been the youngest general in the Wehrmacht, the commander of all Luftwaffe fighter forces, the man whose word shaped battles in the sky from the Channel to Stalingrad.

Now he was a prisoner in all but name. Stripped of command. Forbidden to fly. Under “house arrest” in a hunting lodge that smelled of old wood and failure. Waiting, perhaps, for a firing squad. Waiting for the war to end. Waiting for history to pass sentence on his choices.

The phone rang a third time.

He picked it up.

“Galland,” he said, voice flat.

The reply was clipped, formal, distant. “Herr General, the Führer wishes to speak with you.”

Galland’s heart gave a traitorous little jump. Months of exile had dulled his expectations, not his instincts. Few men in Germany could hear that sentence without feeling some mixture of dread and anticipation.

There was a click. A second of empty static.

Then another voice came on the line. Harsh. Familiar. Unmistakable.

“Galland,” Adolf Hitler said. “I am giving you a last chance.”

Galland closed his eyes. He could almost smell the stale air of the Wolfsschanze, the concrete, the damp maps, the tension. But he was far from any bunker now. Just a single man in a lonely lodge with snow pressing at the windows.

“A last chance for what, my Führer?” he asked carefully.

“Form a squadron,” Hitler said. “Choose whoever you want. Take the jets. Show me what is possible.”

The words hung there like frost.

The jets.

The Me 262.

Galland felt his fingers tighten on the receiver. He stood without realizing it and moved to the window. Beyond the glass, the winter sky was low and colorless. Somewhere out there, under that same sky, the Luftwaffe he had built was being annihilated.

American fighters swarmed over Germany like locusts, silver and relentless. Their bombers came in endless formations, their engines like a storm. His pilots—the best in the world, men he had trained, men he had led—were dying at a rate of fifty per day. The fuel was gone. The factories were rubble. The cities were ash.

And now, at the edge of ruin, Hitler wanted him to form a new squadron.

With the Me 262 jet fighter.

The aircraft that should have been operational three years ago.

“It is late,” Galland said slowly. “Very late.”

Hitler ignored that. “The Me 262 is the weapon that will change everything. I will give you complete authority, Galland. Choose the pilots yourself. The best. A special unit. Show me that the jet can break the enemy. Show me what your fighter arm can still do.”

Galland knew the truth. This wouldn’t change the outcome of the war. It couldn’t. The arithmetic was already written in smoke and blood across three continents.

But something inside him stirred anyway.

He had fought for the Me 262 for years. He had argued, pleaded, shouted at Göring and at anyone else who would listen: this aircraft must be a fighter. It must be used to tear the bomber streams apart. It was the future of air combat. Instead, Hitler had demanded it be turned into a bomber, another misguided hammer for striking at cities when the war had long since moved beyond such theatrics.

Now, with Germany collapsing, with the war all but lost, the Führer was reversing himself.

Too late. Far too late.

Yet this was a chance—perhaps the last chance—to prove what might have been. To show the world what German engineering and German fighter pilots could have achieved if their leaders had not been blinded by delusions.

“Galland?” Hitler’s voice cut back in, irritated. “Do you understand me?”

Galland opened his eyes. Took a breath.

“I understand,” he said. “And I accept.”

He hung up the phone on the most powerful man in Germany and stood for a moment in the quiet, hearing the echo of his own heartbeat.

Then he reached for a pen and a pad of paper.

He began making a list of names.

Within weeks, that list would become the most elite fighter squadron ever assembled. Ten holders of the Knight’s Cross. Aces with hundreds of victories between them. The squadron that would fly the world’s first operational jet fighter into combat.

They would terrify Allied bomber crews for exactly three months.

Then the war would end.

And their story would become something else—not a story of victory, but a story of timing, of wasted potential, of genius arriving too late.

Galland knew it even as he wrote.

Still, his hand moved over the paper, steady and sure, as if this were another operation in a war that could still be won.

He started with a single name.

Gerhard Barkhorn.

Barkhorn arrived first.

A train delivered him to Munich in the grim, gray light of a late winter morning. The station was a shell pocked by shrapnel and scorched by fire. The platform smelled of coal smoke and fear. Refugees huddled with whatever they could carry, eyes hollow, waiting for trains that might never come.

Barkhorn stepped down from the carriage in a uniform that hung a little loose on his frame. His face was gaunt, his skin drawn tight over high cheekbones. His eyes, once bright with the swagger of a young fighter pilot, had sunk into shadows.

He had 301 victories to his name—the second highest-scoring ace in history. He had been flying combat missions almost continuously since 1941. He had been shot down nine times, wounded three. He had lost friends, wingmen, entire squadrons.

The war had hollowed him out, but it had not broken him.

Galland waited for him at the end of the platform, cane in hand, greatcoat collar turned up against the cold. Snow fell in lazy flakes around them, melting on the hot metal of the locomotives.

“Gerhard,” Galland said.

“Herr General,” Barkhorn replied, raising a hand in salute, then letting it fall. Formality felt ridiculous now, but some habits were hard to break.

Galland studied him for a moment. “You look like hell.”

Barkhorn gave a crooked smile. “I’ve been flying piston engines against overwhelming numbers for four years. What did you expect?”

Galland’s smile didn’t reach his eyes. “I expected you to come.”

“How could I not?” Barkhorn shrugged. “You said the magic word. Jets.”

They walked together through the ruined station, sidestepping broken glass and shattered tiles.

“Let me fly a jet,” Barkhorn said quietly as they stepped into the weak daylight. “Let me feel what air combat should be. Just once, before this is all over.”

Next came Heinz Bär, with 220 victories, his reputation as deadly as any man’s in the Luftwaffe. He arrived with a limp, a souvenir from one of the many times he’d been shot down. His eyes held a spark of dark humor that even the last months of the war hadn’t quite extinguished.

Walter Krupinski followed, 197 victories and a crooked grin that made him look younger than he was. Johannes Steinhoff arrived last of the first group, his face still healing from burns suffered when his previous aircraft had crashed during takeoff. The skin on his cheeks and brow was tight and shiny, a patchwork of scars the color of wet clay.

Within two weeks, Galland had gathered ten pilots who all wore the Knight’s Cross. Between them, they had over 1,500 confirmed aerial victories. The average pilot in the squadron was an ace ten times over.

They called the unit Jagdverband 44—JV44. Fighter Detachment 44.

Everyone else called it something simpler.

The squadron of aces.

They established their base at Munich-Riem, an airfield that was more dream than reality, a half-finished shape etched into the muddy ground outside the Bavarian capital. The facilities were primitive. Barracks were repurposed hangars that smelled of fuel, damp straw, and men too tired to care. The runway was a patchwork of craters and repairs, bomb holes filled with crushed stone and asphalt that cracked again every time heavy wheels rolled over it.

Allied fighters strafed the field almost daily. The scream of P-47 Thunderbolts and P-51 Mustangs overhead became as familiar as the sound of their own engines.

The Me 262s themselves were few and temperamental. Galland had requested thirty aircraft.

He got sixteen.

Of those, seven were operational on a good day.

“When those seven Me 262s roar down that runway,” Galland told his men in one of their first briefings, “we are not flying to win the war. We are flying to show what could have been.”

The pilots sat on rough benches, arms crossed, listening in silence. They were not young men anymore. Even those in their twenties had the eyes of men twice their age.

“This unit exists for one purpose,” Galland continued. “We will take this new weapon and show the world what it can do. We will prove that we were right—about the jet, about the way air war should be fought. We will do it knowing that it is three years too late to change anything.”

He drew a breath.

“If you want glory, you came to the wrong place. If you want survival, you definitely came to the wrong place.”

Some of the men smiled faintly at that.

“If you want to fly the future… welcome to JV44.”

The Messerschmitt Me 262 was everything Galland had dreamed of and more.

The first time he walked out to one at Munich-Riem, he felt something he had not felt in a long time.

Wonder.

It sat on the concrete like something not entirely of that era, its lines sleek and swept back, its cockpit perched on the nose like the eye of a predatory bird. Two fat nacelles under the wings housed its Junkers Jumo 004 turbojet engines, each capable of nearly 2,000 pounds of thrust when they were in the mood to cooperate.

He walked slowly around the aircraft, cane tapping softly at his side. His fingers brushed the cold metal skin. The swept wings. The heavy nose that housed four MK 108 30mm autocannons.

Each of those cannons fired 650 rounds per minute. Each round was a short, brutal cylinder of high-explosive promise. A single hit could blow a two-foot hole in a bomber. Three or four hit home and a B-17 didn’t just die. It disintegrated.

The Me 262 could reach 540 miles per hour in level flight—faster than any Allied piston-engine fighter by a margin that might as well have been another century. It could climb to 30,000 feet in under seven minutes. Where a P-51 Mustang needed twelve.

It was, in every way that mattered, a glimpse of the air war to come.

Galland put a hand on the edge of the cockpit and hoisted himself up, dropping into the seat with a grunt. The canopy arched overhead, framing the world in curved plexiglass. The instrument panel spread out in front of him, familiar and alien at the same time.

He could smell paint, oil, cold metal.

“Beautiful, isn’t she?” the crew chief said from the ladder.

Galland looked at the jets on the wings, the cannons in the nose, the runway ahead.

“She’s three years late,” he said quietly. “But yes. Beautiful.”

The first time he took one into combat, he felt like he was being reborn.

Late February 1945. Gray skies over southern Germany. The world below buried in snow and soot.

He eased the throttles forward and listened as the Jumo engines began their slow, eerie whine, rising in pitch like ghosts screaming through steel. Turbojets were not like piston engines. They did not roar instantly to life. They spooled up slowly, reluctant, temperamental, demanding patience from men who had lived too long by the rule that hesitation kills.

The aircraft rolled, gathering speed. At first it felt sluggish, heavy, uncertain. Then, as the turbines reached power, the world changed.

“It was like being shot out of a cannon,” Galland would say years later.

The acceleration pinned him to the seat. The runway blurred. Snow at the edges of his vision streaked into white-gray smears. The Me 262 surged forward with a kind of cold eagerness, then leapt into the air as if relieved to leave the ground behind.

Within seconds, he was past 400 miles an hour.

The piston fighters he’d flown all his life—Bf 109s, Fw 190s—suddenly seemed like antiques. He had once thought them sleek, fast, lethal. Now they were tractors next to a race car.

He climbed steeply, the altimeter needle spinning.

At 25,000 feet, he leveled off.

Ahead, over Munich, hung the dark, purposeful shapes of a B-17 formation—Fortresses, their contrails like chalk lines on the cold blue canvas of the sky. Around them fluttered the smaller, darting shapes of P-51 escorts, silver bodies catching the sun.

The Americans saw the lonely dot of his jet coming and maneuvered to intercept. The Mustangs tilted, turned, dove to meet him.

Galland simply pushed the throttles forward.

The Me 262 surged ahead again, and the P-51s fell behind as if they had thrown out anchor cables. Their pilots opened fire anyway, .50 caliber tracers arcing through the thin air, falling farther and farther behind his tail.

He felt contemptuous, almost giddy.

This is what air combat should be.

He moved out in front of the bomber stream, a thousand yards ahead. Then he rolled the jet upside down, yanked back on the stick, and dove underneath, rolling upright again as he came up toward the oncoming wall of metal.

Head-on attack.

Closing speed: over 600 miles per hour.

He had two seconds. Maybe less.

The lead B-17 swelled in his gunsight, a gray-green loaf of death bristling with machine guns, spewing streams of tracers that reached blindly toward him.

He waited until the bomber filled the circle.

Then he pressed the trigger.

The four MK 108 cannons roared, their recoil hammering through the airframe. Four streams of 30mm shells leapt out in a ravenous, converging line.

He saw the impacts as flashes along the B-17’s nose, across the cockpit, along the wing root. The right wing seemed to shudder, then fold upward in a grotesque, impossible angle. Fire blossomed from the fuel tanks. The bomber rolled, nose dropping, breaking apart even as it began to fall.

Four seconds.

That was all it took.

He flashed through the formation, buffeted by turbulence from shattered air, then pulled up hard, lungs and eyes straining under the G-forces. The bombers’ gunners fired wildly at empty sky. The Mustangs clawed after him, but he was already far away, climbing back to safety.

Untouchable.

He landed at Munich-Riem an hour later, the runway rushing up, the jets slowing with an odd reluctance as if they did not understand the concept of “stop.”

When he taxied to the hangar and shut the engines down, the sudden silence felt unreal.

The ground crew cheered.

Barkhorn rolled in behind him, his own Me 262 pulling up in a graceful arc. He climbed out and slapped the side of the fuselage.

“This,” Barkhorn said, grinning for the first time in months, “is what we should have had in 1942.”

Galland met his gaze, the exhilaration fading as quickly as it had come.

“Yes,” he said. “That is exactly the tragedy.”

For exactly ninety-one days, JV44 would be the most feared fighter unit in the European theater.

Allied bomber crews learned to dread the thin white contrails that approached them at unnatural speed. The jets would appear from nowhere, make a single devastating pass, and vanish before the escorts could even begin to catch them.

“We started calling them ‘blow-throughs,’” an American B-17 pilot would say later. “You’d see this streak like a silver knife and then, bang, one of the Forts in the formation just… came apart. Then nothing. No dogfight. No chase. Just ghosts.”

In March alone, JV44 shot down around fifty Allied aircraft.

Their kill-to-loss ratio was staggering—almost five to one in favorable circumstances. For a moment, if you looked only at that column in the logs, it was possible to imagine that the jet had arrived as the miracle weapon propaganda had promised.

But Galland knew better. He knew the numbers that actually mattered.

Germany had produced roughly 1,400 Me 262s during the entire war.

Of those, only about three hundred would ever serve as operational fighters. The rest were built as bombers per Hitler’s misguided insistence, or as trainers, or they were destroyed in their factories or on railcars by Allied bombing long before they smelled aviation fuel.

On the other side, the Americans were producing over a thousand fighters every month. Every month, B-17 and B-24 production combined exceeded five hundred bombers. The British added hundreds of Lancasters and Mosquitos.

Galland did the math in his head often enough that it became a kind of prayer.

Even if every Me 262 shot down five Allied aircraft—an absurdly optimistic assumption—they would barely make a dent in the bomber offensive. The Americans could absorb those losses and keep coming. Industrial war was a storm, and Germany had brought an umbrella.

And the fuel situation was worse.

The Me 262’s turbojets drank fuel like thirsty beasts. They consumed it at five times the rate of piston engines. A single sortie for JV44 required tens of thousands of liters of jet fuel. By April 1945, Germany’s synthetic fuel plants were twisted skeletons under repeated Allied bombings. The fuel simply did not exist.

The cruelest irony, however, was not the logistics or the output tables. It was the vulnerability built into the heart of the jet’s operation.

Takeoff and landing.

The Me 262’s engines were temperamental, fragile things made in a hurry with the wrong alloys and the wrong expectations. They needed several minutes to spool up to full power. During that window—those agonizing minutes between taxi and true flight—the jet was slower than a conventional fighter and almost helpless.

Allied commanders figured this out quickly.

They stopped trying to chase Me 262s in the open sky where the jets could run rings around them. Instead, they stationed squads of P-51s and P-47s near known jet bases, circling high above or lurking just beyond flak belts. They waited.

They attacked as the jets took off or as they came in to land, low on speed, low on fuel, committed to a narrow strip of earth.

JV44 lost more pilots on their own runway than they did in combat.

Galland watched it happen again and again.

The pattern seared itself into his nightmares.

An ace with a hundred victories would roll down the pockmarked strip, the Me 262’s engines screaming, the heavy nose lifting as the jet reached for the air. Just as the wheels left the ground, specks appeared in the sky, growing into the slicing shapes of Mustangs.

The P-51s would dive, guns spitting white-hot streams of tracer fire.

The jet, engines still struggling for full thrust, could not dodge with the grace it had at speed. A wing would shear off. Fuel would blossom into fire. The aircraft would cartwheel across the field, trailing debris and flame and pieces of a man who had once believed he was invincible.

Once, Galland stood on the edge of the runway when it happened.

The pilot was a veteran from the Eastern Front, a man whose name had appeared on so many victory reports that it felt like part of the Luftwaffe’s furniture.

The Me 262 lifted off. The Mustangs came. The air filled with tracers.

The jet slammed back down in a skid of fire and smoke, plowing across the field. The cockpit ripped open. A body tumbled out and lay still.

Galland limped toward the wreckage on his cane, smoke cutting his throat, heat pushing against his face. The crew chief knelt beside the twisted figure, hands bloody, eyes wide.

“Is he—?” Galland began.

The chief shook his head.

Galland turned away, eyes burning from more than smoke.

It was death by arithmetic.

No amount of skill could outrun the numbers forever. No single masterpiece of engineering could compensate for a thousand factories bombing out fuel plants, trucking routes, and rail yards.

Quality did not matter when quantity was overwhelming.

Timing did not matter when you were three years late.

In the quiet moments between sorties, Galland sat in his bare little office at Munich-Riem and did calculations on scrap paper. Sometimes he began them for comfort. They never ended that way.

What if.

It was the most dangerous phrase in any language, but he couldn’t escape it.

What if the Me 262 had been operational in 1942?

He imagined the same aircraft rolling off assembly lines three years earlier, when the RAF’s bomber offensive was still struggling for mass, when the US Army Air Forces were only beginning to flex their industrial muscles, when Germany still had fuel, still had veteran pilots by the hundreds instead of handfuls.

He thought of 5,000 Me 262s in service by mid-1944 instead of a few hundred.

With a two-year head start, Germany could have produced thousands of jets. They would have dominated the skies over Europe. Allied bombers would have flown into a meat grinder every time they crossed the Channel. Casualties would have been unsustainable. The pressure on Britain and America might have forced negotiation. The invasion of France might have failed before it began.

The entire course of the war could have diverged.

Instead, the Me 262 had arrived when Germany was already bleeding out. When its best pilots were dead. When its cities were ruins. When the enemy’s factories were in full roar, turning ore into airplanes faster than bombs could break them.

JV44 was proof of concept.

Nothing more.

A demonstration flight for history, staged on a collapsing stage.

And Adolf Galland, once Germany’s youngest general and, by many accounts, its greatest fighter tactician, found himself leading a squadron whose true purpose was to prove how badly Hitler and Göring had failed.

He had known it was coming long before the phone rang in the hunting lodge.

The confrontation that sealed his fate had happened in November 1944, in a room that still smelled of power then.

Göring had summoned his fighter commanders to headquarters to explain something that no one could explain anymore: why the Luftwaffe was failing to stop American daylight bombing raids.

They gathered in rows, uniforms pressed, faces lean. Men who had crawled out of burning wrecks. Men who had watched squadrons reduced to flights, flights to pairs, pairs to empty chairs at mess.

Göring entered the room bloated with decorations and the swollen arrogance of a man who had not been in a cockpit in years. He looked at the men he blamed for his failures, and they looked back at the man they blamed for theirs.

Instead of listening, he began accusing.

He accused them of cowardice. Of defeatism. Of sabotaging his orders. He told them they were not fighting hard enough, not attacking aggressively enough, not dying heroically enough to meet his expectations.

The words washed over Galland like acid.

For months, he had presented data, numbers so clear even a politician could have understood them if he’d wanted to. The Americans were producing a thousand fighters a month. Germany could not replace losses. The fuel was running out. The experienced pilots were dead or exhausted beyond reason. The Me 262 jets that could have turned the tide were being held back, misused, delayed, turned into bombers for Hitler’s fantasies.

Göring had called these facts “defeatist talk.”

Now, in this room, the chief of the Luftwaffe was questioning their courage.

Galland felt something inside him snap.

He stood up. The room fell silent. All heads turned.

He reached for the Knight’s Cross around his neck—the medal he had earned in the sky over England, over Russia, over the smoking remains of a hundred dogfights—and tore it off.

He walked down the aisle between the rows of officers and laid the medal on the table in front of Hermann Göring.

“Here,” Galland said. “Take this back. I will not wear it when my honor is being questioned.”

No one breathed.

Göring stared at the medal. Then at Galland. His face turned a mottled purple, his mouth tightening into a line that promised consequences.

But he said nothing.

He couldn’t.

Galland was too famous, too respected by the pilots. Executing him would risk open rebellion in the fighter arm. Besides, there was still a chance the war might be turned around. Even Göring was not yet mad enough to shoot his best tactician on the spot for speaking truths.

Instead, he took a slower revenge.

He stripped Galland of his command. Removed him from operational control of the fighter arm. Banished him from the centers of power, sending him off to the hunting lodge with orders to remain quiet and irrelevant.

And that is where Hitler’s call had found him, weeks later.

Disgraced.

Powerless.

Seething.

And yet, when the chance came to prove himself one last time—to prove his men right, if not his leaders—he took it.

JV44 fought on through March and April 1945, a flame burning bright while everything around it fell into darkness.

On the other side of that flame, men felt the burn.

High over Germany, in the frigid cockpit of a B-17 named Lucky Lady, Captain Frank Malloy sat hunched behind the controls, frost crackling along the inside of his windshield. The bomber shuddered with every gust of high-altitude wind. The engines droned. The oxygen mask itched against his face.

“I don’t like those contrails,” his co-pilot muttered, pointing.

Far behind and slightly above the bomber formation, a thin white line was cutting through the sky. It was thinner than a bomber’s trail, more needle than rope. And it was closing fast.

“Tally ho, twelve o’clock high!” the tail gunner shouted over the intercom. “Something’s coming in fast—real fast!”

“Fighters?” Malloy asked.

“Doesn’t look like any fighter I’ve seen—Jesus, look at that thing!”

The contrail resolved into a shape that didn’t match anything in the recognition manuals: two engines under swept wings, a narrow fuselage, no propellers.

The jet sliced in, not in the circling, swirling pattern of a dogfight, but like a bullet: one straight, purposeful line.

“Head-on attack!” Malloy yelled. “Hold formation!”

In the nose, the bombardier and navigator gripped their guns tighter, fingers white on the triggers. Excited, terrified voices filled the intercom as other Fortresses called the same sighting.

Then the German jet was there.

Malloy barely had time to register the green-gray cross on its side, the flash of glass where the cockpit should be, when four bright lines of fire leapt from its nose.

The world exploded.

Lucky Lady shuddered violently. The nose seemed to disappear in a hail of smoke and fire. Instruments shattered. Metal screamed. For a moment, Malloy thought he had been blown out of the sky. Then he realized they were still flying—barely.

The intercom was a chaos of shouts, some of them cut off mid-sentence.

He stole a glance to his right and saw another Fortress, one he’d flown alongside on a dozen missions, break apart. The wing ripped off in a clean, terrible motion. The fuselage spun, trailing flame.

“Jesus,” the co-pilot whispered. “What the hell was that?”

“Jet,” Malloy said hoarsely. “Gotta be one of those jets intel’s been talking about.”

Behind them, the Me 262 flashed away, already far out of range, climbing back to the thin, safe heights.

The Fortresses closed ranks around the hole left by their destroyed comrade and pushed on toward their target.

In the sky above, P-51 escorts turned and dived, too late, chasing contrails that faded into nothing.

They were learning.

They would learn faster than Germany could build jets.

American fighter pilots adapted their tactics. They started to think not like duellists, but like hunters around watering holes. They stopped trying to catch the jets at full speed. They went for the moment when the Me 262 was least supernatural.

The moment when gravity and Newton remembered it was just another object in the air.

A P-51 pilot named Jack “Tex” Harrigan circled high above a German airfield one pale afternoon, engine tickling the edge of a stall.

Down below, the shape of the airfield lay etched in cracked concrete and fresh craters. Smoke drifted from a distant building. Black flak puffs marked the edges of an invisible box around the field.

Tex kept his Mustang just outside the box, as he’d been briefed. Let the ground gunners waste ammunition on nothing.

“Ground control, this is Eagle One,” he said into his radio. “No jets yet. Just a couple of trucks moving around.”

“Hold position, Eagle One,” the controller replied. “They’ve got to come home sometime.”

Tex smiled grimly. “Roger that. We’ll be here with the welcome wagon.”

Ten minutes later, a dot appeared at the edge of the sky. Then another. Silver shapes resolved into aircraft gliding in with their engines throttled back, conserving fuel. Their approach was surprisingly gentle, almost lazy.

“Contact,” Tex said softly. “Two bandits at ten o’clock, low, on final.”

He eased the Mustang into a shallow dive. His wingmen followed.

The Me 262s committed to their landing. Their flaps came down. Their nose pitched slightly up as they flared toward the runway, engines spooling lazily.

Tex slid his Mustang into position behind the trailing jet, his thumb resting lightly on the trigger.

“I almost feel bad about this,” one of his wingmen said quietly.

Tex didn’t answer. He lined up the shot.

At 300 yards, he squeezed the trigger.

Six .50 caliber guns spat fire. Tracers stitched across the sky and into the jet’s tail, walking forward. The Me 262 seemed to stumble, its left engine belching flame, then tearing free altogether. The aircraft rolled, wings dipping, and slammed into the runway in a flare of sparks and fire.

By the time the flak guns opened up, Tex and his flight were already climbing away, engines screaming.

Later, over coffee in a smoky mess hall, someone would ask him how it felt, ambushing jets like that.

“Like shooting a racehorse at the barn door,” Tex said. “But I’ll tell you this much: They weren’t going to change the war. Not then. We weren’t going to let them.”

Back in Munich-Riem, Galland tried to push those thoughts away. He focused on the missions in front of him, on keeping his remaining pilots alive long enough to make their point.

April 26, 1945.

Two weeks before Germany’s surrender.

Galland stood on the remains of the runway at Munich-Riem as dawn bled slowly over the Alps. The jagged white teeth of the mountains caught the first light, turning them into ghostly shadows against a bruised sky.

American forces were less than thirty miles away. Russian forces were pushing in from the east. The airfield lay under intermittent artillery fire, the thumps and distant whistles a constant reminder that the ground war was finishing what the air war had started.

Half the runway was unusable, cratered and chewed. The other half had been patched again and again by ground crews working with shovels, broken machinery, and sheer stubbornness.

Galland had seven operational Me 262s.

One more mission.

Intelligence reported a formation of American B-26 Marauder medium bombers approaching Munich. The raid wouldn’t change the outcome of anything. The city was already rubble. The war was already lost.

But for Galland, strategy had shrunk to something more intimate.

He cared about his men.

He cared about going down fighting.

He limped toward his jet.

It sat at the edge of the runway, its nose painted with the number that had become part of his legend: red 13. The ground crew had applied the paint in defiance of superstition months earlier. Galland had approved.

If fate wanted him, it could find him easily.

His crew chief, a teenager named Klaus who should have been worrying about exams instead of engine tolerances, stood at the wing root, helmet in hand. His eyes were tired. The dark smudges under them belonged on a much older face.

Klaus helped Galland up the ladder.

“Sir,” he said quietly as he tightened the straps around Galland’s chest. “You don’t have to do this. The war is over.”

Galland smiled, a small, tired twist of the mouth.

“That’s exactly why I have to,” he said.

Klaus swallowed. “Then… good hunting.”

Galland settled into the cockpit, the harness biting into his shoulders. He ran his gloved hands over the familiar layout: throttles, gauges, switches. Above him, the morning sky waited.

“JV44, this is Galland,” he said into the radio. “One last dance, gentlemen. Remember: short bursts, head-on passes. Make every second count.”

“Understood, Herr General,” Barkhorn’s voice came back, steady. “We’ll give them something to remember us by.”

The Jumo engines began their eerie rising scream as Klaus signaled the start-up. Blue flame licked from the exhausts. The jet trembled, straining against its own brakes.

Galland released them.

The Me 262 surged forward, wheels thumping over patched concrete. The acceleration pressed him back into the seat. At sixty knots, the runway vibrations blurred into a steady hum. At ninety, the nose came up. At a hundred and thirty, the ground fell away.

He pulled the gear up and climbed steeply into the pale light, the airfield falling away beneath him in a geometric patchwork of hangars, craters, and blackened scars.

His wingman tucked in beside him, another jet gleaming in the dawn.

They climbed toward the Danube.

They found the bombers there—a box formation of B-26 Marauders, twelve aircraft in a tight, disciplined rectangle, each one bristling with guns. Above and behind them, like hawks over a flock, circled P-51 escorts.

Galland did not hesitate.

He rolled his jet inverted, nose pointing down toward the bombers, then pulled through in a half-loop, building speed. The altimeter spun faster, the airspeed indicator climbing into numbers that would have destroyed older fighters.

He rolled upright and came in head-on.

The closing speed was insane. At that moment, time was measured not in seconds but in fractions of a heartbeat.

He centered the lead bomber in his gunsight.

Pressed the trigger.

The 30mm cannons hammered. The Me 262 shook under the force of its own fire. Galland saw the Marauder’s nose vanish in a spray of wreckage—glass, aluminum, pieces of men. The cockpit simply ceased to exist.

Then he was past, the bomber dropping away in flames, tumbling toward the river.

He pulled up, lungs flattened by G-forces, vision narrowing. He forced himself to breathe, to blink, to think.

For one instant, he felt triumph.

Then the P-51s came.

They had anticipated this attack. They had learned the patterns. Four of them broke from their racetrack above and dove on Galland from angles that cut off his best escape routes.

He jinked left, then right, hauling the jet into evasive maneuvers that would have shaken most men unconscious. For a moment, he thought he’d shaken them.

Then one Mustang slid in behind him, lining up.

Galland knew the feeling of being hunted. He had done this to others enough times to recognize the rhythm.

Tracers reached out like white-hot fingers.

He felt the impacts as short, brutal punches along the jet’s fuselage. Heard the scream of tearing metal. The cockpit vibrated with a new, ugly frequency.

The right engine coughed, spat flame, and died. The left kept turning for a few seconds longer, then joined its twin in silence.

The Me 262 became something else in that instant.

A 17,000-pound glider.

He shoved the nose down, trading altitude for airspeed, buying seconds with height. Smoke filled the cockpit. Warning lights glowed uselessly.

Below him, the torn earth bore the fading scars of recent bombs. A crater yawned like a wound in the ground, a circle of exposed dirt and broken edges maybe fifty feet across.

He aimed for it.

The controls were heavy. His knee screamed with every movement. The world smeared into motion.

The Me 262 hit the ground hard.

Much too hard.

The landing gear folded like matchsticks. The jet slammed into the crater, skidded, rolled, and tore itself apart in a shower of metal and dirt. The canopy cracked. The seatbelt bit into his chest. For a moment, blackness tunneled in at the edges of his vision.

Then there was silence.

Snowflakes drifted lazily down into the crater, landing on hot metal and disappearing in tiny hisses.

Galland opened his eyes.

He was still alive.

Pain roared into him a moment later. His knee was a firestorm. Blood soaked his flight suit. He could see bone through the torn fabric if he forced himself to look down.

He decided not to.

He unbuckled the harness with fingers that didn’t quite feel real and pushed himself up out of the ruined cockpit, crawling onto the edge of the crater. Every movement sent lightning through his leg.

Above, circling high, his wingmen watched.

They saw a figure in a tattered uniform climb out of the broken jet.

They saw him wave them away.

They answered with a waggle of their wings—one last salute—then turned for home.

Galland sat on the edge of the crater, breathing in shallow, ragged pulls. The Me 262 lay behind him in twisted fragments, the dream of a war-winning jet lying as broken as the ideology that had birthed it.

Two weeks later, Germany surrendered.

JV44’s final tally was as brutal and simple as any ledger.

Approximately fifty confirmed victories in three months of operations.

Twenty-seven pilots lost. Most of them killed not in glorious duels at high altitude, but on takeoff or landing, ambushed at the moment when their machines were weakest.

Seven Me 262s destroyed on the ground or cannibalized for parts, not felled by enemy fighters but by lack of fuel, lack of metal, lack of time.

Adolf Galland survived.

His shattered knee never healed properly. For the rest of his life, he walked with a cane, the rhythm of his steps forever altered by that impact in a muddy crater near the Danube.

He also lived another fifty-one years.

Long enough to see jet fighters become the standard for every air force on Earth.

Long enough to watch American F-86 Sabres and Soviet MiG-15s duel over Korea in echoes of the fights he had always imagined over Europe. Long enough to see the Me 262, the ugly, brilliant prototype of it all, displayed in museums as a revolutionary design built for a nation that could no longer afford revolutions.

Long enough to meet, and eventually befriend, the American and British pilots he once tried to kill.

After the war, in a bare interrogation room with windows that let in too much light, an American officer sat across from Galland with a notebook. The officer’s uniform was crisp, his expression controlled. He was not interested in vengeance. He was interested in understanding.

“What would have changed the outcome?” he asked.

He expected talk of tactics, of different deployments, of clever strategies.

Galland surprised him.

“We needed jets earlier,” he said simply. “Not in 1945. In 1942.”

The officer frowned. “The Me 262?”

“Yes.” Galland leaned back, the cane across his knees. “If we had operational Me 262s in significant numbers in 1942, your bombing campaign would have failed. Your losses would have been unsustainable. You would have negotiated. Or at least delayed. Everything after that would be… different.”

The American scribbled notes. “But in 1945?”

Galland’s smile was sad and sharp. “In 1945, you were building a thousand fighters a month to our hundred. You had fuel. We didn’t. You could lose ten aircraft for every one of ours and still win. And you did.”

The interrogator looked up. “So the Me 262 didn’t matter?”

“Oh, it mattered,” Galland said. “It proved the future of air combat. It showed what could be done. But it also proved something else: that genius arriving too late is indistinguishable from failure.”

JV44 flew for exactly ninety-one days.

In that time, they shot down more Allied aircraft per pilot than any other unit in the Luftwaffe. They proved beyond doubt that jets were the future. They demonstrated what German aviation might have achieved with better leadership and earlier deployment.

They changed nothing.

The war ended when it was always going to end.

The tide that had turned in 1942, in factories and shipyards and oil fields far from any burning city, kept rising until it drowned everything, jets and knights and aces and maps and medals.

The squadron of aces was theater, not strategy.

A demonstration of what might have been, staged at the exact moment when it could no longer matter.

Years later, in a museum in a peaceful country, a Me 262 stood on a polished floor under clean white lights. Its green and gray camouflage had been restored, its nose cannons sealed, its engines empty shells of history.

Visitors walked past, reading plaques. Some paused, frowning, trying to connect the sleek shape to black-and-white film they had seen or stories they had heard.

A boy in a baseball cap stared up at the jet, eyes wide.

“Dad,” he said, tugging at his father’s sleeve. “That one looks fast.”

“It was,” his father said. “Fast and dangerous. First of its kind.”

He read the plaque aloud. “Messerschmitt Me 262. First operational jet fighter. Introduced too late to affect the outcome of World War II.”

“Too late?” the boy asked. “How can something be too late if it’s that fast?”

The father smiled faintly. “Because speed’s not the only thing that matters.”

Across the hall, an older man walked with a cane, his accent softening the English words he spoke to the guide. His hair was white. His eyes were sharp.

He had flown aircraft once that no longer existed outside of places like this.

He had learned the hard way that wars were not won by the best airplane, or the bravest pilot, or the cleverest general.

They were won by factories, by railroads, by oil wells. By clocks.

Someone asked him what he had taken away from those days, from the jet age he had helped usher in with blood and fire and lost friends.

“In war,” he said, “timing isn’t everything.”

He paused, leaning on his cane, looking up at the swept wings and quiet engines of the Me 262.

“It’s the only thing.”

News

40 Marines Behind 30,000 Japanese – What They Did in 6 Hours Broke Saipan

They were officially Marines, but everyone knew them as “thieves” – fighters with discipline problems, brawlers and troublemakers that regular…

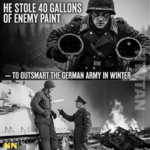

He STOLE Gallons of Enemy Paint To Make 15 Sherman Tanks Disappear

He STOLE Gallons of Enemy Paint To Make 15 Sherman Tanks Disappear They were surrounded by snow, steel, and silence….

Karen threw hot coffee at my brother-in-law for the window seat not knowing I own 62 airports

Karen threw hot coffee at my brother-in-law for the window seat not knowing I own 62 airports Part 1…

Karen Told Me I Couldn’t Have a Pool — So I Built One That Broke the HOA!

Karen Told Me I Couldn’t Have a Pool — So I Built One That Broke the HOA Part 1…

HOA Karen B*CTH steals kids medical equipment gets hit with grand larceny charges and lands in jail!

HOA Karen B*CTH steals kids medical equipment gets hit with grand larceny charges and lands in jail! Part 1…

I saw my daughter in the metro with her child and asked her: ‘Why aren’t you driving the car….

I saw my daughter in the metro with her child and asked her: “Why aren’t you driving the car I…

End of content

No more pages to load