German Officers Never Expected American Smart Shells To Kill 800 Elite SS Troops

December 17, 1944. Elsenborn Ridge, Belgium.

SS Obersturmbannführer Max Hansen stood in the freezing pre-dawn darkness, watching his elite troops prepare for what should have been a breakthrough.

Snow crusted under his boots as he shifted his weight, breath a pale cloud in the bitter air. Somewhere beyond the tree line, American artillery guns were silent for now, black silhouettes against a sky just beginning to pale from ink to iron gray. The forest smelled of pine sap, cold earth, cordite, and unwashed wool.

Hansen’s men moved like shadows through the mist, checking weapons, tightening straps, stomping feeling back into numb feet. Orders passed in low voices, clipped and confident. These were not green boys. Not here. Not with him.

He was no ordinary officer and they were no ordinary troops.

He had survived Kharkov, watching Russian armor pour across fields like steel locusts. He had survived Normandy, where British artillery had smashed entire companies into the ground in minutes. He had survived more battles on the Eastern Front than most men could name. When other officers talked about “experiences,” he had smiled, silently remembering the smell of burning fuel in a Ukrainian winter or the sound of tanks grinding over frozen corpses.

Now he commanded the First SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment of the Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler, Hitler’s personal bodyguard division. The cuff title on their sleeves—Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler—was worn with a pride that bordered on religion.

These were the best troops Germany had left.

Veterans. Fanatics. Winners.

And directly in front of them stood Elsenborn Ridge, held by inexperienced American units of the 99th Infantry Division. The Battle Babies, they were called. Replacements. Latecomers. Many had never seen combat.

On paper, this should have been easy.

Hansen went over his orders one last time in his head, though he already knew them by heart.

Break through the American lines. Seize the ridge. Open the road to Liège and Antwerp.

The entire northern shoulder of the Ardennes offensive—Hitler’s gamble to split the Allied front—depended on his success.

He looked out over the dark, undulating silhouettes of the snow-covered hills. Somewhere beyond them, in the sleeping American positions, young men from Ohio and Kansas and New York lay shivering in foxholes, wondering if this quiet would hold until Christmas.

It wouldn’t.

A younger officer, Hauptsturmführer Krüger, approached, boots crunching softly. His nose was red above his scarf, but his posture was that of a man expecting to win.

“Carter groups are ready, Herr Obersturmbannführer,” Krüger said. “Pioneers have marked the lanes. Infiltration teams are in position.”

Hansen nodded. “Artillery?”

“Batteries report ready. First barrage at 0530 exactly. Weather reports stable. Visibility low but acceptable.”

He glanced at his watch, the hands barely visible in the dim light. 0517.

Thirteen minutes until the world changed.

He reviewed the intelligence report one last time. It was a simple piece of paper, edges smudged from handling, but its words had shaped his confidence.

Americans spread thin. Positions hastily prepared. 99th Division inexperienced. No significant armored reserves nearby. German doctrine was clear: elite infantry, properly led, could break through defensive positions through infiltration tactics. Small groups would probe for weaknesses. Follow-up waves would exploit breaches. Artillery would suppress enemy guns.

He had done this dozens of times. In Russia. In France. In Italy.

He knew how it was supposed to go.

At 5:30 a.m., right on schedule, the first German artillery shells screamed overhead and slammed into the American lines.

The frozen earth shook, throwing up geysers of dirt, snow, and shattered trees. The thunder rolled back over the forest, echoing through the pines. Fire licked briefly at the sky in dozens of places, then vanished into churning smoke.

Hansen watched the barrage through his field glasses, the world reduced to flashes and flickering shadows. The twin villages of Rocherath and Krinkelt—small clusters of Belgian houses huddled along icy roads—disappeared in an angry cloud of fire and dust.

“Forward,” he said.

Radios crackled. Whistles blew. The grenadiers flowed into motion.

They moved in the classic infiltration pattern. Small teams, widely dispersed, advancing through the forest toward the American lines. Some slipped between trees, using the trunks for cover, boots sinking into the snow with muted crunches. Others crawled along shallow gullies, their camouflage smocks streaked with white paint for winter operations.

The first reports came in after twenty minutes, thin voices over the field telephone.

“We have penetrated their forward positions.”

“Resistance light. Some Americans falling back.”

“Prisoners captured. They seem inexperienced.”

Hansen allowed himself a small, grim smile.

The Battle Babies were breaking, just like the report said they would. He could almost see it: young Americans tumbling out of their foxholes, jerseys and flannel under ill-fitting coats, eyes wide under steel helmets that still looked new.

Sometime later, he would remember this moment as the last time anything about this battle made sense.

Because then the American artillery responded.

He had expected counter-battery fire, of course. He had fought through Soviet barrages that lasted for hours, waves upon waves of shells walking forward with grinding inevitability. He had seen British and Canadian guns pound positions until nothing remained but splinters and bones.

But this was different.

The first American shell exploded not in the ground, but exactly twenty feet above one of his advancing companies.

It burst with a flat, sharp crack that felt wrong somehow, and the shrapnel scythed downward like a steel rain. Men who had flattened themselves behind trees or thrown themselves into shallow depressions screamed as jagged fragments punched into shoulders, necks, spines. Snow geysered not upward, but outward, as the blast carved an invisible circle of death.

Another shell came in seconds later.

Again, it detonated in the air, at precisely the same height.

Then another.

And another.

Every single shell burst at almost the perfect altitude.

A company commander’s voice came over the radio, urgent and strained.

“Herr Obersturmbannführer! The American shells are detonating above our positions. Our men have no cover. Casualties are severe!”

Hansen frowned. He ducked instinctively as another distant explosion rolled over the forest.

Airbursts required precise timing fuses. They were not new as a concept. A shell could be set to explode after a certain number of seconds in flight, theoretically at a certain altitude. But it required meticulous calculations, experience, good observation of weather and flight times. Even then, getting it right consistently was nearly impossible. Some shells would burst too high, their shrapnel scattering uselessly. Others would hit the ground before their timers expired.

And yet the Americans were doing it every single time.

He pressed the receiver closer to his ear.

“Continue the attack,” he said. “Close with the enemy. Once you are among them, their artillery will not risk firing.”

He hung up and listened to the distant thunder of the American guns.

For a moment, a memory from Kharkov flashed through his mind: a Russian battery firing with terrifying speed, a hillside erupting like a volcano. He remembered thinking then that he had seen the worst artillery could do.

He was wrong.

Over the next six hours, he watched his carefully planned attack disintegrate.

His troops would advance, moving as doctrine demanded.

American artillery would respond with a precision he had never seen before.

Every shell burst at the optimal height.

Foxholes offered no protection. Trenches became killing zones. The very cover they had learned to trust—dirt, logs, shallow holes scraped in frozen ground—became irrelevant when death came from above.

Even hardened veterans who had survived Stalingrad and Kursk were being shredded by shrapnel raining down from the sky.

Nearby, a young SS grenadier named Otto knelt in a shallow foxhole, helmet pulled low, rifle clutched so hard his hands ached. He had grown up in Hamburg, listening to party rallies on the radio, seeing posters of heroic soldiers crushing cartoonish enemies under their boots. He had believed every word.

Now, for the first time, he wondered if belief could stop steel.

The first shells had seemed almost familiar, the dull thumps of impact muffled by snow. He had pressed himself into the earth, feeling the ground tremble, thinking: I know this. I was trained for this.

Then the airbursts began.

Forty meters to his left, a shell detonated in midair, showering his squad with white-hot fragments. One man’s scream cut off almost instantly. Another fell on his back, arms thrown wide, blood spraying from his shredded throat in a grotesque fan.

Otto screamed without realizing it and tried to dig deeper, clawing at frozen dirt.

“Stay down!” his squad leader shouted, but there was nowhere left to go.

Shrapnel hissed into the ground around them, like a swarm of enraged hornets. A fragment struck the tree above Otto and spun off, hot and bright, nicking his cheek. The blood felt oddly warm in the freezing air.

He pressed his face into the dirt and tasted mud and snow and something metallic.

By afternoon, Hansen had committed his second wave.

Then his reserves.

The pattern never changed.

German infantry would mass for an attack, grouping for a final push.

Within minutes, American shells would explode above them with surgical precision.

Hansen grabbed his field telephone, anger finally leaking into his voice.

“Artillery command!” he snapped. “Can you suppress the American guns? Concentrate every battery you have on their positions!”

The answer came back grim and weary.

“We’re trying, Herr Obersturmbannführer, but we cannot locate their firing positions quickly enough. Their counter-battery fire is extraordinarily accurate. Our guns are being silenced as soon as they open up.”

Hansen clenched his jaw.

He pictured the artillery duels in Russia—chaotic affairs where guns would fire, displace, fire again, moving like chess pieces under an invisible hand. It had been a deadly dance, but it had possessed a kind of symmetry. You could win, or you could lose, but you understood the rules.

The Americans weren’t displacing.

They were firing continuously from fixed positions with impossible accuracy, as if they knew exactly where every one of his companies was and exactly how high to detonate every shell.

It was as if they could see through the trees. As if every movement on his map was mirrored on some unseen board miles behind the American lines.

On the other side of the ridge, in a cramped, sandbagged fire direction center, Lieutenant Jack Marshall ran a pencil over a firing chart so fast the graphite broke.

The FDC smelled of sweat, wet wool, and coffee that had been boiled too long. A field phone hissed and crackled on the table. Maps covered every surface, marked with grease pencil and arrows that changed with every frantic report.

“Fire Mission, Fire Mission!” the voice on the line shouted, barely audible over the background roar of battle.

“Go ahead, Able Three,” Marshall said, cupping a hand around the receiver.

“Company-sized enemy element forming in the woods east of the Krinkelt road, grid five-four-seven nine-two-one. They’re massing for another push. We need steel on them now, lieutenant. Now, or they’re coming through.”

Marshall’s eyes flicked to the map. He traced the coordinates with his pencil, then raised his voice.

“Battery! Adjust! New grid, five-four-seven nine-two-one. VT fuses. Two rounds each gun, fire for effect on my command.”

Behind him, six 105mm howitzers sat in their revetments like patient beasts, their barrels already blackened from a long morning’s work. Gun crews huddled around them, faces smeared with soot and mud, waiting.

“VT?” Corporal Henson asked, looking up from his own notes. He was short, with a Tennessee drawl and fingers that moved with machine-like speed over the plotting board.

Marshall nodded. “You heard me.”

He glanced at the battered metal crate tucked in the corner. Stenciled on its side were the letters VT in fading yellow paint.

Proximity fuses.

The men had heard rumors about them for months. “Smart shells,” some called them. “Gizmo rounds,” others said, wary. There had been lectures from serious-looking officers and even more serious-looking scientists in stateside classrooms, chalkboards filled with diagrams of radio waves and reflected signals.

In theory, it was simple: the fuse contained a tiny radar set. When the shell approached the ground—or a solid object—the echoes from its own radio waves would spike, and the fuse would trigger detonation at just the right altitude.

In practice, it felt like witchcraft.

“Fire Direction Center, this is Baker One,” another voice cut in on the line. “Be advised, this works. Whatever you boys cooked up in those labs, it’s chewing them to pieces out here.”

Marshall didn’t have time to feel proud. Pride came later, if at all.

“Guns loaded?” he shouted.

“Loaded with VT!” a sergeant yelled back.

Marshall took a breath. In his mind’s eye, he pictured young men in gray uniforms moving through the trees, rifles held low, trusting in old rules that no longer applied. He felt the weight of what he was about to do, and the necessity of it, both at once.

“Battery,” he said, voice steady. “Fire for effect.”

The howitzers spoke in unison.

Six shells leapt from their barrels, each one wrapped around a fist-sized device of glass, copper, steel, and battery acid that had traveled a long road from American factories to this Belgian hillside.

In the trees east of Krinkelt, Otto heard a faint whistling overhead.

He flattened instinctively, pressing himself into the snow.

For a moment, nothing happened.

Then the shell detonated above him.

On the evening of December 18, as darkness crept back over the frozen forest, a runner stumbled into Hansen’s command post, face raw from the cold, eyes too wide.

“Herr Obersturmbannführer,” he said, saluting awkwardly, “one of our patrols found this in a crater near Krinkelt. It did not explode.”

He set the object on the table.

It was an American 105mm artillery shell, its casing dirty and scored from impact. The fuse had partially separated in the blast of its own failed detonation.

Hansen felt an odd, surgical calm settle over him.

“Clear the table,” he said.

Maps were pushed aside. Coffee cups were moved. A candle flickered in the draft as he bent over the shell.

He had examined thousands of artillery rounds in his career—German, Russian, British. He knew the rhythm of their design: steel, explosive, fuse. Many secrets, but all of them mechanical.

He unscrewed the nose cone carefully, hands steady despite the fatigue and frustration grinding at his nerves.

Beneath it, instead of the simple mechanical timer he expected—springs, gears, and tiny clockwork—he saw something that made no sense at all.

Nestled inside the fuse casing was what looked like a miniature radio set: tiny vacuum tubes smaller than his fingertip, a battery assembly, coils of copper wire, resistors, capacitors, a delicate antenna.

“What is this?” he muttered.

He called for his signals officer.

The man who entered a few minutes later looked out of place in an SS field headquarters. His uniform was slightly rumpled, his glasses slid down his nose, and he had the distracted air of someone used to thinking about circuits rather than tactics. Before the war, he had worked as an engineer at Telefunken, designing radios civilians had once used to listen to dance music and propaganda speeches.

Hansen pushed the open fuse across the table.

“Explain.”

The officer adjusted his glasses and leaned in, fingers carefully moving aside a twisted lead. As he examined the components, the color drained from his face.

“This appears to be a radio transmitter and receiver,” he said slowly. “There is a high-frequency oscillator, a detector circuit, a power source. Herr Obersturmbannführer… This is the VT proximity fuse.”

“The what?”

“Variable Time. Proximity. It has been rumored. The theory is sound. The fuse sends out radio waves while the shell is in flight. When those waves reflect off the ground—or any solid object—the change in the signal triggers detonation at the optimal altitude.”

Hansen stared at the tiny tubes, the impossibly delicate wiring.

“The shell decides when to explode.”

“Yes, sir,” the engineer said. “No calculations needed. No timing required. The shell decides when to explode.”

Hansen felt something cold settle in his stomach that had nothing to do with the winter air.

“Can we build this?” he asked.

The engineer shook his head immediately, almost violently.

“The miniaturization alone is beyond our current capabilities. These vacuum tubes are smaller than anything in German production. And they survive being fired from a gun barrel. That means they are designed to withstand forces of twenty thousand times gravity, maybe more.”

He looked up, eyes wide in the candlelight.

“Sir, this represents a level of engineering precision we cannot match. Not now. Perhaps not for years.”

Hansen leaned back and exhaled slowly.

For a long moment, the only sounds in the command post were the creak of the wooden walls and the distant, muffled thump of artillery.

He had thought the day’s horror lay in the casualty reports—columns of numbers that had turned 2,000 elite troops into 1,200 battered survivors. A forty percent casualty rate in less than forty-eight hours. Against, supposedly, an inexperienced American division.

But this… this was worse.

This was an equation.

He dismissed the engineer and waited until he was alone. Then he drew his notebook closer and picked up his pencil.

He listed what he had seen inside the fuse.

Thirty individual components, at least.

Four miniature vacuum tubes.

Fifteen resistors.

Ten capacitors.

A battery assembly.

An antenna mechanism.

A trigger circuit.

Each requiring precision manufacturing. Each requiring quality control. Each requiring assembly by skilled workers who knew what they were doing. Each fuse a tiny, self-contained masterpiece of engineering designed to survive the violence of artillery firing.

This wasn’t a prototype.

It wasn’t a one-off wonder weapon cobbled together in some secret lab.

This was a production model.

Which meant the Americans were mass-producing these devices.

He thought about the barrage his men had endured that first day. Rough estimates from his artillery liaison suggested American guns had fired around 3,000 shells at his sector alone.

If even twenty percent were equipped with proximity fuses, that meant about 600 “smart” shells in one day at one location.

And he knew there were similar battles across the entire Ardennes front—St. Vith, Bastogne, Monschau. Every sector where German infantry tried to mass, American artillery reached out with an invisible hand and swatted them down.

If each sector received similar support, that meant thousands of proximity fuses expended daily.

He flipped to a fresh page and wrote another number.

The U.S. Army had around 200 artillery battalions in Europe.

If even half were equipped with these fuses, and each fired 100 rounds per day—a conservative figure, given what he’d seen—that was 10,000 fuses consumed daily just in Europe.

The Americans were also fighting in Italy. In the Pacific. On islands whose names he barely recognized.

The mathematical implications were staggering.

He thought about Germany’s situation.

He had visited factories in the Ruhr before the offensive. He had walked through cavernous halls that once hummed with the steady, confident rhythm of peacetime production, now echoing with a strained, hollow sound. Machines ran on reduced schedules due to coal shortages. Workers—many of them forced laborers whose loyalty was enforced at gunpoint—operated poorly maintained equipment under the watchful eyes of guards.

Quality control inspectors glanced at parts that would have been rejected a year earlier and passed them through with a shrug. The war needed volume, not perfection.

Germany’s entire electronics industry employed perhaps 50,000 skilled workers. These men and women were responsible for radio equipment, radar sets, communications gear, fire-control systems, and everything else in a war that increasingly depended on invisible waves and silent signals.

And now, somehow, they were supposed to also replicate American proximity fuses.

If a skilled German technician could assemble one complete fuse in eight hours of work, that was one fuse per day per worker.

To produce 10,000 fuses daily would require 10,000 skilled technicians working full-time on nothing but fuses.

Germany didn’t have 10,000 electronics technicians to spare.

The Americans apparently did.

He pulled out an intelligence report he had dismissed as propaganda weeks earlier, more out of habit than analysis. It described American war production in fantastical terms: Ford Motor Company converting automobile plants to aircraft production. General Motors producing tank engines. Chrysler making tanks.

The report had claimed that American automobile factories had been retooled in months to produce military equipment at scales exceeding Germany’s entire industrial output.

He had laughed when he read it. Another boast from a decadent, overconfident enemy.

Now, holding this impossible fuse, he understood.

They weren’t exaggerations.

If anything, they were underestimates.

The proximity fuse itself was impressive engineering.

But what truly terrified him was what it represented.

The Americans hadn’t just solved a technical problem.

They had created an industrial process that could mass-produce the solution.

He thought about Germany’s wonder weapons—the V-2 rocket, the Me 262 jet fighter, the massive “King Tiger” tanks.

Technological marvels, every one of them.

Each V-2 required thousands of man-hours, produced in underground factories by slave labor in conditions so terrible that men died building weapons meant to kill others. Germany had launched approximately 3,000 V-2s during the entire war, at enormous cost, with marginal military impact.

The proximity fuse was at least as sophisticated, perhaps more so. But the Americans had produced not 3,000 of them.

Millions.

The difference wasn’t technical.

It was systemic.

He continued calculating, no longer thinking about Elsenborn Ridge as a line on a map but as a dot in an equation.

Each proximity fuse required high-grade aluminum, copper for circuits, specialized glass, rubber for seals, precision steel. He multiplied those requirements by millions of units and felt his pencil slow.

Germany was rationing aluminum for aircraft production. The Americans were using it for artillery fuses.

The copper requirements alone would exceed Germany’s entire annual production.

But the Americans had done it while simultaneously producing over 96,000 aircraft in 1944. Tens of thousands of tanks. Hundreds of ships. Millions of tons of ammunition.

He wrote down a simple comparison.

Germany’s total aircraft production for 1944: roughly 40,000.

Armored vehicles: around 25,000.

Total fuses of all types for all munitions: perhaps 500 million.

America’s production for 1944: more than 96,000 aircraft. Over 29,000 tanks. Perhaps 15 million proximity fuses alone. Hundreds of millions of conventional fuses on top of that.

The ratio wasn’t 2:1.

It wasn’t even 3:1.

In many categories, it was 5:1 or 10:1.

And American production was still increasing.

German production, despite heroic efforts and propaganda slogans, was beginning to decline under the weight of strategic bombing, material shortages, and a workforce stretched to the breaking point.

Hansen closed his notebook slowly.

The mathematics were irrefutable.

Germany was fighting an industrial war against an enemy with five to ten times the production capacity.

No amount of tactical brilliance could overcome that disparity.

No amount of soldier courage could bridge that gap.

No amount of ideological fervor could change the arithmetic.

The war was already lost.

Not because of this battle. Not because of this weapon. But because the entire strategic foundation of Germany’s war effort had been built on a lie.

The lie that will could overcome material.

The lie that quality could defeat quantity.

The lie that German superiority was destiny.

The proximity fuse had simply proved all of it false.

It was mathematical proof written in steel and electronics.

A proof that couldn’t be argued with, couldn’t be denied, couldn’t be overcome.

He sat in the darkness, holding the evidence of Germany’s defeat, knowing that no one in the chain of command would accept what it meant.

He wrote his after-action report by candlelight.

He described the tactical situation in professional, detached language: the strength of American defenses, the pattern of attacks, his unit’s casualties. He noted the failure to achieve objectives, the stubbornness of the enemy.

Then he added a paragraph he knew would be unwelcome.

“The enemy has deployed a proximity fuse that detonates artillery shells at optimal altitude without requiring timing calculations. This weapon makes traditional infantry tactics obsolete. Foxholes and trenches no longer provide protection. Based on examination of a captured fuse specimen, this device represents industrial and technical capabilities significantly exceeding current German production capacity. Recommendation: Strategic reassessment required.”

He sealed the report and gave it to his orderly.

It would go up the chain of command: division, corps, army. It would be read, noted, and ultimately ignored.

Because the truth it contained was too terrible to acknowledge.

Over the next three days, his regiment continued to assault Elsenborn Ridge.

Each attack followed the same pattern.

German infantry advanced.

American artillery responded with perfect airbursts.

German casualties mounted.

Eight hundred became a thousand.

A thousand became twelve hundred.

The 12th SS Panzer Division joined the attack. Teenagers with hard eyes and Hitler Youth armbands tucked under their camouflage. Hardened veterans with eyes that had seen too much. All of them moved forward when ordered.

None of it mattered.

American artillery fired over 10,000 rounds per day at German positions around Elsenborn. A significant percentage were equipped with VT proximity fuses. Each one exploded with perfect precision, shredding men and trees and illusions.

German soldiers learned that the old rules no longer applied.

Digging in didn’t help.

Dispersing didn’t help.

Speed didn’t help.

The shells found them.

The shells burst above them.

The shells killed them.

On December 20, German high command finally accepted reality at the tactical level, if not the strategic.

Elsenborn Ridge could not be taken.

The northern shoulder of the offensive had failed.

After the battle, Hansen’s regiment was pulled back to refit. Of the 2,000 men who had attacked on December 17, fewer than 1,200 remained.

Forty percent gone in less than a week.

Against an inexperienced American division.

In a quiet corner of an American field hospital behind the lines, Lieutenant Jack Marshall sat on a cot, sipping lukewarm coffee and staring at nothing. He hadn’t slept in twenty-six hours. Orders and coordinates still flickered through his mind in a dizzying blur.

A chaplain walked by, offering a kind word here, a small joke there. Nurses moved from bed to bed, tending to men who had lost limbs, eyes, hope.

Jack’s battery had taken casualties too. A shell had landed close to one of the guns, killing a loader and wounding two others. The VT fuses didn’t care whose side you were on once the metal started flying.

A captain sat beside him, another artillery officer with the same hollow look.

“Your fancy fuses work,” the captain said at last.

Jack looked up. “Yeah.”

“Intel says they’re tearing up the Germans all along the line. Elsenborn, St. Vith. Hell, somebody said they used them on a U-boat pack in the Channel months ago. Naval boys got the first ones.”

Jack nodded. He had heard the stories. VT shells detonating close enough to aircraft to rip wings off with shrapnel. Anti-aircraft gunners cheering the first time they saw a plane simply vanish in a cloud of debris.

“You ever feel weird about it?” the captain asked. “About…” He gestured vaguely with his hand, as if the right word were somewhere in the air between them. “About the ‘smart’ part? The shell deciding when to blow?”

Jack thought of the diagrams, the radio waves, the little glass tubes. He thought of the coordinates. He thought of what must be happening in those woods every time he said “fire for effect.”

“I feel weird about all of it,” he said at last. “Then I think about their shells landing on our guys, and I figure I’d rather have the better math.”

“Math,” the captain repeated, tasting the word. “Yeah. Guess that’s what it comes down to now.”

On the German side, the word he chose was the same, though he framed it differently.

Mathematik.

Hansen’s after-action report reached SS Oberstgruppenführer Sepp Dietrich, commander of the Sixth Panzer Army, days later.

Dietrich read it with growing anger, thick fingers tightening on the paper as he came to the section about “weapons that make traditional infantry tactics obsolete.”

At the next command briefing, surrounded by maps that no longer meant what they pretended to show, he addressed his officers.

“I have received reports,” he said, voice heavy, “claiming that the Americans have some kind of miracle fuse that renders our tactics obsolete. This is defeatist nonsense. The attack on Elsenborn failed because of inadequate preparation and insufficient aggression, not because of enemy technology.”

Hansen sat silently, eyes unfocused on the table.

He knew arguing was pointless.

The Nazi regime had been built on the myth of German superiority, of the triumph of will over matter, of racial destiny and iron resolve. To acknowledge that America had surpassed Germany in industrial and technological capability would undermine the entire ideology.

So the truth was rejected.

Officers who raised concerns were labeled defeatists.

Reports of American capabilities were dismissed as propaganda.

And the war continued, with men dying in attacks that could not succeed against weapons they could not counter, in a war that was already lost.

After the war, when production figures were declassified, Hansen’s fears were confirmed.

The VT proximity fuse program had been massive.

By late 1944, American factories were producing approximately 40,000 proximity fuses per day.

Total production exceeded 22 million units.

Twenty-two million miniature radar sets, each one more complex than most German radios, all produced in less than two years of full-scale manufacturing.

For comparison, Germany’s entire production of all types of fuses for all types of munitions during the entire war was roughly 500 million units. Simple mechanical fuses. Basic timing devices. Crude, compared to the tiny brains inside the American shells.

The Americans had produced 22 million smart fuses while also producing hundreds of millions of conventional ones.

The scale was incomprehensible.

At Elsenborn Ridge alone, American artillery had fired over 30,000 shells in the first three days. Conservative estimates suggest that 20 to 30 percent were equipped with proximity fuses. That meant between 6,000 and 9,000 smart shells in three days at one location.

And Elsenborn was just one battle on one front.

Hansen survived the war.

He was interrogated by American technical intelligence officers in 1945, sitting in a clean, well-lit room that felt more unreal to him than any bunker or battlefield.

They asked about his report on the proximity fuse.

“Did you understand what you were facing?” one officer asked, pen poised above a notebook.

Hansen nodded slowly.

“I understood we were fighting a war we could not win,” he said. “Not because of cowardice. Not because of poor leadership, though there was certainly enough of that. Because we were fighting an industrial system operating at a scale we could not comprehend.”

“Then why,” the American asked, “did the attacks continue?”

Hansen looked at his hands, at the faint scars from cold and cordite and burning metal.

“Because acknowledging the truth,” he said quietly, “would mean acknowledging that our entire ideology was built on lies. German superiority. The triumph of will. Victory through determination. All lies. The proximity fuse proved that mathematics matters more than mythology. But mythology was all we had left.”

The American officer closed his notebook softly.

“For what it’s worth,” he said, “we found your report in captured German archives. It was marked ‘Filed. No action required.’”

Hansen smiled bitterly.

“Of course it was,” he said.

Years later, historians would point to Elsenborn Ridge as a microcosm of Germany’s defeat.

Time and again, competent professionals had presented accurate assessments of Germany’s deteriorating position. Admiral Canaris had warned about American industrial capacity. Albert Speer had known that Germany couldn’t win a production war. Field commanders had recognized American technical superiority in everything from radar to logistics.

All had been ignored.

Because the regime valued ideology over evidence.

They believed that will could overcome mathematics.

That racial superiority could defeat industrial capacity.

That mythology mattered more than reality.

They were wrong.

At Elsenborn Ridge, young German soldiers died in foxholes that no longer protected them, killed by weapons they couldn’t understand, produced by factories they couldn’t imagine, in a war that was already decided long before they picked up their rifles.

The proximity fuse didn’t just kill German soldiers.

It killed the illusion that Germany could win.

It was mathematical proof that the industrial war was already over, and no amount of courage or sacrifice could change that equation.

The shells kept falling.

The mathematics kept calculating.

And the Reich kept sending men forward, blind to a reality it refused to see.

In the end, reality didn’t care what anyone believed.

The smart shells at Elsenborn Ridge proved that beyond any doubt.

News

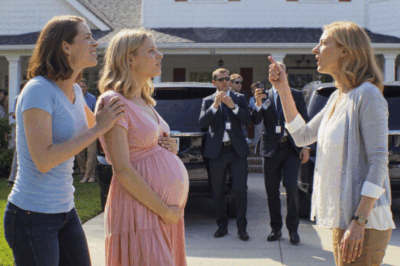

HOA Karen Tried Forcing My Pregnant Sister to Strip for Verification — Federal Agents Arrived

HOA Karen Tried Forcing My Pregnant Sister to Strip for Verification — Federal Agents Arrived Part 1 I will…

They Mocked Me As A ‘Decorative Wife’—Now I’m Their Boss

They Mocked Me As A ‘Decorative Wife’—Now I’m Their Boss Part 1 “You know, Yara, you really should consider…

I WON $450M BUT KEPT WORKING AS A JANITOR SO MY TOXIC FAMILY WOULDN’T KNOW. FOR 3 YEARS, THEY…

I won $450m but kept working as a janitor so my toxic family wouldn’t know. For 3 years, they treated…

“GET OUT OF MY HOUSE BEFORE I CALL THE COPS,” MY DAD YELLED ON CHRISTMAS EVE, THROWING MY GIFTS…

“Get out of my house before I call the cops,” my dad yelled on Christmas Eve, throwing my gifts into…

MY MOM ANNOUNCED: “SWEETHEART MEET THE NEW OWNER OF YOUR APARTMENT.” AS SHE BARGED INTO THE

My mom announced: “Sweetheart meet the new owner of your apartment.” As she barged into the apartment with my sister’s…

At the family dinner I was sitting there with my broken arm, couldn’t even eat. My daughter said”…

At the family dinner I was sitting there with my broken arm, couldn’t even eat. My daughter said”My husband taught…

End of content

No more pages to load