General Noticed Bruises on the Face of a Female Soldier — Then, What He Did Next Shocked Everyone

Part I — The Morning the Room Went Quiet

Humidity lay over Fort Haven like a wet blanket, blurring the razor edges of the motor pool and turning the parade field’s dust to a chalk that clung to boots. Inside the mess hall, though, the air conditioners were holding the line. Trays clattered, spoons rang, and the low rumble of a hundred conversations filled the long, fluorescent-lit room.

Sergeant Clare Méndez stepped through the door with her cover tucked beneath one arm and the other hand tightly gripping her tray. She had timed her entrance for the middle of the break between PT and morning formation, when the senior staff usually cleared out and the junior soldiers filled in. She had fooled herself that she could disappear into the river of bodies, collect a cup of oatmeal and a banana, make it to a corner, count her breaths, and get out.

The room didn’t let her. Sound slipped, like someone had turned down a radio. She kept walking, each step too loud in her own head. Her right cheek was swollen; the purple had gone slick at the edges to a sickly yellow. A split traced the bow of her lip like a bad pencil line. She felt it crack when she tried to smile at Specialist Parker behind the milk dispenser. He froze, eyes darting to the side and then away. No one wanted to be the first to see.

At the far table, Major General Thomas Roth was halfway through his oatmeal. He didn’t stand for effect. He didn’t need to. Men like him take up a different kind of space—gravity, not volume. The silver at his temples matched the stars on his collar. He was known for discipline, not softness. The kind of commander who read regulations like gospel and expected you to live them the way you meant it. He had been in long enough to have opinions about jungles and deserts and whether you could ever trust a man who ironed his own name tapes.

He saw the bruises the way you notice a missing wall in a building you designed. Not as a detail but as a failure of structure. He saw the hesitation that lived in her shoulders, the way her eyes slid away from a captain at a table two rows over. Captain Doyle. Company commander, jaw like a billboard, the kind of officer who had mastered the smile that never reached his eyes. He lifted a mug and smirked into his coffee.

“Sergeant Méndez,” Roth said. His voice carried without shouting. Conversations stuttered and died. Heads turned because they were trained to. In the silence, spoons sounded like gunshots.

Clare’s boots beat a metronome across the tile. She stopped in front of her commanding general, tray trembling just enough to tip the water in her cup.

“Sergeant,” he said again, quiet. “Who did this to you?”

Her fingers flexed against the plastic ridge of the tray. Months of math flashed across her face: the calculus of careers and reprisals; the weight of whispered warnings—don’t make trouble, don’t be that girl, don’t you know how this works. Her jaw worked once. Twice.

“Training accident, sir,” Captain Doyle said from two tables over, rising just enough to be seen. “She tripped on the range. Nothing—”

Roth turned his head slowly. The room felt the temperature drop. “Then why,” he asked in a voice that had made colonels correct themselves mid-sentence, “do you look nervous, Captain?”

A ripple ran through the mess hall like wind through tall grass. Doyle’s smirk faltered. He forced a laugh that didn’t know where to land. “With respect, sir, I think you’re—”

Roth’s wedding ring rang off the metal table with a violence that cracked the bone in the room. “You think I don’t know a cover-up when I see one?”

Clare didn’t plan what she did next. She unbuttoned her cuff and slid her sleeve up, the way you would show a corpsman where it hurt so they could find the vein. The purple didn’t stop at her cheek. It stair-stepped up her forearm in fingerprints and ovals. Some were old. Some were not.

She didn’t speak. She didn’t have to. Chairs scraped. A sergeant first class at the far end of the room stepped forward anyway. Then a specialist. Then a private first class whose hands had been shaking for ten minutes. Then the medic on breakfast shift, jaw tight. It wasn’t a mob. It was a wall building itself, brick by brick, with human beings who remembered their values and stood under them.

Roth stood. The chair legs shrieked against the tile. He nodded once to his aide. “Escort Captain Doyle to the Provost Marshal’s office. Effective immediately, he is relieved of command pending investigation. Collect his sidearm.”

Doyle started to protest. The aide—Lieutenant Neeley, forty pounds lighter and two paygrades below—didn’t blink. “Sir, I’ll need your weapon.” Doyle’s mouth moved. His hand found his holster as if it had never held a pistol before. He looked at the room and didn’t find a single friendly face to call by name. He put the pistol on the table. The scrape of metal carried.

“Sergeant Méndez,” Roth said, voice shifting from flint to something that had a pulse in it. “Do you have a battle buddy?”

“Staff Sergeant Nguyen, sir,” she got out. Tara Nguyen appeared at her elbow as if conjured. She had half a blueberry muffin on her tray and eyes like steel wool. “Right here.”

“Good,” Roth said. He didn’t say, I’m sorry. He said, “No soldier stands alone under my command. Not one. Do you understand?”

“Yes, sir,” Clare said. Her lip stung when she said it. Tears burned behind her eyes and she kept them where they belonged. There would be time. Maybe.

“Go with the SARC,” he said, jerking his chin. “Get medical documented. You will not return to that company area. You will not be alone with any member of that chain of command. Staff Sergeant Nguyen, you have her until I say otherwise.”

“Yes, sir,” Nguyen said. “She’s got me.”

Roth turned in a slow circle and the mess hall tried to look busy and failed. “Let me be exceptionally clear,” he said into the room, his voice that tight, controlled register that meant someone’s career was about to be divided into before and after. “If you knew and said nothing, that changes today. If you suspected and made a joke, that ends now. If you retaliate against a soldier for reporting, I will end you on paper, and you will deserve it. We are not that unit. We will not be that unit. Dismissed.”

Chairs squealed. Conversations flared back up, brittle, then honest. Someone clapped once, caught himself, then everyone looked down and then back up and felt something shift they wouldn’t be able to name for two weeks.

Outside, the flag hardly moved. Dust lifted and fell.

Roth stood at the door as the SARC—a staff captain with kind eyes and a spine—took Clare’s arm and steered her away. He watched until she was in a golf cart and moving. Then he rolled his shoulders back and felt the weight settle where it always had. He found his aide. “Get me JAG. Get me CID. And get me the battalion commander. Now.”

The aide jogged. Roth tugged at the cuff of his shirt. He felt the edge of a scar under his starched sleeve. It was old and thin but there. Twenty-three years ago, he had buried a soldier who had smiled through a bruised lip. He had been a captain then. He had believed the lie that there was nothing he could do about the way men were in rooms where rank and violence got confused with permission. He had learned better. He had promised a ghost and God and himself that if he ever had the weight to move the world, he would.

Inside, the air conditioner rattled. Outside, the day kept climbing.

Part II — The Cost of Silence and the Geography of Truth

There is a math to reporting harm that no one teaches you at basic training. On one side of the ledger: regulations—Army Regulation 600-20, the SHARP program, EO hotlines, laminated posters that peel at the edges in latrines. On the other side: the culture—whispered reputations, punitive details, barracks doors that click shut on secrets, COAs that look like favors and smell like rot. In between: a human being trying to do their job and go home with their dignity.

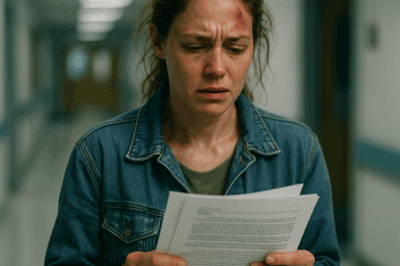

Two hours after the mess hall, a uniformed investigator from the Criminal Investigation Division sat across from Clare in a windowless conference room. The walls were the color of neglect. A digital recorder sat between them like a third person everyone had to pretend wasn’t there.

“I’m Special Agent Lyle,” she said. “This is Captain Park from JAG. I know you’ve told your story once already to Sergeant—Ngo?”

“Nguyen,” Clare corrected, voice hoarse.

“Nguyen,” Lyle said, nodding. “We need to build this right. We’re going to ask you to tell it again. Every time will feel like ripping something open. I’m sorry. But every rip is a stitch later. Do you understand?”

Clare nodded. “Yes, ma’am.”

“Start at the first time.”

Clare stared at her hands for a second. Her knuckles were scraped where she’d grabbed a doorframe last night. She took a breath and found the words.

“First time was in May,” she said. “It started with comments. Nothing anyone would put in a counseling statement. Little things. ‘Smile more, Sergeant.’ ‘You’re tense.’ ‘You don’t know how lucky you are to have a commander who gives a damn.’ He’d linger after formation. He’d put a hand on the small of my back to ‘guide’ me when the hallway was empty.”

“When did it escalate?” Park asked. Her voice was low, careful.

“June,” Clare said. “We had a late-night layout for a range. He kept us until 2300. I stayed after to lock up the arms room. He ‘helped.’ He blocked the doorway. He said I made him feel disrespected when I corrected him on a safety SOP in front of the platoon. He grabbed my arm.” She slid her sleeve back again. The yellow at the edges of the bruise looked older now under the fluorescents. “This was last night,” she said. “It wasn’t the first time. It was just the one you could see.”

“Why didn’t you report in June?” Park asked. She didn’t put judgment on it. She wrote as if collecting weather.

“Because I like my job,” Clare said. “Because I remember what happened to Specialist Harmon when she reported in 2018. They moved her barracks room to the far end of the hallway and gave her CQ every weekend for three months ‘by the book’ and told her she was paranoid. Because my platoon sergeant said, ‘I’ll take care of it,’ and then we got a new guidance policy on hair in formation but nothing else changed. Because Captain Doyle told me he’d make sure I never saw a promotion board if I kept embarrassing him. Because he’s friends with the battalion commander and the battalion commander calls me ‘kiddo’ and once patted me on the head as a joke. Because you weigh things you shouldn’t have to weigh.”

“Did you document anything?” Lyle asked.

Clare slid a small notebook from her cargo pocket. “Dates. Times. Locations. Witnesses. Texts.” She tapped the worn cover. “I write things down.”

Park’s mouth tightened in a way that meant anger without oxygen. “Good,” she said. “We’ll photograph your injuries. You’ll give a statement. You’ll get a medical exam for your safety and for evidence. Then you’re going to sleep in a safe room in the brigade headquarters tonight. Staff Sergeant Nguyen will be with you.”

“What happens to him?” Clare asked.

Lyle exchanged a glance with Park. “He’s in the Provost Marshal’s custody. He’s being advised of his rights under Article 31. He’s going to sit until we finish the initial interviews. Pending results, the commanding general has already signed a memorandum suspending him from command and restricting him to quarters. That’s more than a lot of people get.”

“Okay,” Clare whispered. “Okay.”

“How’s your jaw?” Park asked.

“It hurts when I talk,” Clare said.

“Then stop,” Park told her. “Drink water. Let us carry this for a minute.”

On the other side of post, the command suite at Division Headquarters smelled like coffee and printer ink and the ghost of brass polish. General Roth stood with his G-1, the SJA (Staff Judge Advocate), and the brigade commander, a colonel who looked like a man who ironed his socks and had been doing it since 1989.

“You can’t just relieve him in the dining facility,” Colonel Mercer said, cheeks blotching. “Sir, with respect, we have procedures. Article 15 is a tool. We have to be careful with undue command influence. CID investigates. JAG advises. We don’t hang people in public.”

“We don’t hang anyone,” Roth said. “We also don’t ignore bruises on a sergeant’s face because it’s convenient.”

“With respect, sir,” Mercer said, and he meant the words the way a man does when he thinks if he says them enough he can still get his way. “Doyle is solid. He’s aggressive. He gets results. Retention is up.”

“Retention is up because we have a war on and a bonus,” Roth said. “And ‘aggressive’ isn’t a compliment if your soldiers flinch when you walk in a room. When did you last walk your barracks? After Taps. Without your command sergeant major in front of you.”

Mercer opened his mouth.

Roth didn’t let him find excuses. “I don’t give a damn if he wins a streamer while he breaks the people who held it the whole time. Discipline without care is a fancy way to say cruelty. Here’s what’s going to happen. JAG will advise CID. CID will do their job. While they do, Captain Doyle is out of command. Effective now, promote from within temporarily. You will not assign Sergeant Méndez a duty that keeps her in the same building with any person who has ever called me to ask for a favor on Doyle’s behalf. You will not let a single one of her NCOER bullets get touched by his hand. You will put a guard on the CQ desk with a name I can trust. And, Colonel?” He let the title cool. “If I hear the word ‘gossip’ come out of your mouth to describe what she did, I’ll swap your parking spot for a slot in the motor pool.”

“Sir,” Mercer said. His face had gone pale. He reached for his beret like a habit. “Yes, sir.”

Roth turned to the SJA. “We’re going to handle this by the book,” he said. “We’re going to be visible, we’re going to be fast, and we’re going to be right.”

“Yes, sir,” Lieutenant Colonel Shankar said. “We’ll initiate a formal Commander’s Critical Information Requirement, notify CID central, set up a victim advocate. We’ll prepare a flagging action. And sir—” he hesitated. “You should know IG has two open hotline complaints on this unit. Both from primary females. Both mention retaliation by the same captain and a climate of fear.”

Roth closed his eyes for half a second. An image flickered at the back of his mind—white gloves against black cloth, a triangle folded tight, a mother’s hands. He opened his eyes. “Add me to the interview list,” he said. “My door is open. Put it in writing. I want it on every bulletin board. Use my name.”

“Yes, sir,” Shankar said, already writing.

Roth walked to the window. The parade field looked calm. Calm is what before always looks like when you don’t know that’s what it is. He thought of the night twenty-three years ago when a private had shown up in his office with a split lip and a story choked in her throat she could not get out. He had believed the wrong man. He had learned the smallest taste of what it feels like to live with yourself afterward. He had sworn. He was going to keep that oath if it ended him.

“Get me the PAO,” he said. “We’ll need to manage this right. Not for optics. For the truth.”

Part III — The Hearing You Didn’t See Coming

Forty-six days after the mess hall, the courtroom was packed. Soldiers filled the benches in Class Bs. Women in bun uniforms you could clock like a pulsing line in a convoy. Men with lanyards who didn’t want to be seen leaning. The judge sat under the seal like a man who had taught himself to love silence because it kept his face still.

It was an Article 32 preliminary hearing to determine whether there was sufficient evidence to go to a general court-martial. The government had charged Captain Doyle with violating Article 128 (assault consummated by a battery), Article 93 (cruelty and maltreatment), and Article 133 (conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman). They had added an 134 (general article) catch-all for the threats he’d sent by text—screenshots projected on a screen that made men flinch and women go still.

Doyle’s attorney tried to turn the hearing into a debate about chain of command and how many push-ups are too many. He introduced training records. He used the word “discipline” like a talisman. He called a company clerk who swore that Captain Doyle had never raised his voice, and Private First Class Lopez stepped into the witness box, hands shaking, and told the court he had heard the thud in an office and the sound of a woman saying “stop.”

“What did you do?” the defense attorney asked, eagerness alive in his voice.

Lopez swallowed. “Nothing,” he said, raw. “I did nothing. I’m sorry.”

The defense attorney smiled as if he’d gotten what he wanted. The judge’s jaw worked as if he had an opinion he was not allowed to say. The prosecutor leaned forward. “Private Lopez, why did you do nothing?”

Lopez looked down at his hands, the callouses of a mechanic shining. “Because he writes my leave,” he whispered. “Because he told me I was lucky to be here after my DUI and could be unlucky real fast. Because Specialist Harmon.” He didn’t look up. “Because I was a coward.”

“Is that why you’re testifying now?” the prosecutor asked.

“Yes, ma’am,” he said.

When it was her turn, Clare walked to the stand with Staff Sergeant Nguyen at her shoulder. Her uniform fit clean. Her hair was pulled tight. The bruise had faded to a brown that would live there for another week and then another month in a ghost of yellow. She took the oath. She told the truth. Her voice shook on the first sentence and then found a path it hadn’t had last month.

“Sergeant Méndez,” the defense said in the tone of a man who had asked that question before and liked the answer he usually got. “You are twenty-seven? No spouse? No children?”

“Yes,” she said.

“You work long hours?”

“As do all of us,” she said. He smirked. She did not.

“Is it true that you once told your platoon you’d ‘rather die than go to sick call’?”

“Yes,” she said. “It was a joke. A bad one. We were on a ruck. It was hot.”

“Is it possible,” he said, voice smooth as oil, “that you tripped? That you are mistaken?”

She pushed her sleeve back up and let the room see the fingerprint marks again, now faint but there. “Were you ever a sergeant, sir?” she asked him. “No?” She rewound her face into something that fit court better than mess halls. “I did not trip,” she said. “He put his hands on me. He threatened me. He told me I would never see a board if I didn’t remember my place. I remember the smell of his coffee. I remember the exact angle of my desk when I fell against it because I’d drawn it wrong in my mind a thousand times since. That’s the kind of thing you don’t mistake.”

The judge watched her closely. She could feel the room’s silence like a pressure change. She kept her eyes on the judge and not on the place where Doyle sat, not because she was afraid but because he was no longer relevant to her life and didn’t deserve her eyes.

When the hearing ended, the judge took twenty minutes and came back with a face that had decided something. “There is probable cause to believe the accused committed the offenses charged,” he said. “This matter will be referred to a general court-martial.”

Roth sat in the back row, his uniform perfect and his eyes bloodshot. He did not nod. He did not smile. He did not clap because ceremonies had rules and he would not cheapen this by pretending it was a celebration. He looked at the room full of soldiers, at the way the men in the back row shifted their weight and the way the women on the aisle sat up straighter. He felt something old unclench.

The JAG captain—the same one who had taken Clare’s statement in a windowless room—found him by the door. “Sir,” she said, voice low. “Heads up. That hot climate assessment we ran? It’s worse than I thought. Four female soldiers in Bravo Company have independent allegations. Two men in weapons platoon. Your colonel told them to ‘handle it at the company level.’”

Roth took the paper. For a second he remembered standing in another mess hall in another country twenty years ago when a private had flinched at a sergeant’s voice and he had convinced himself he had misread it. For a second he remembered his wife—Charlotte—sitting at their kitchen table in Quantico, telling him about her client at JAG who had to resign after filing a report and how systems do not fix themselves. He had promised her. He had done what he could. It had not been enough. It was going to be now.

“Relieve Mercer,” he said. “Today. For cause. Negligent command climate. Pending IB investigation. Assign the deputy as acting until I can find someone who knows the regs and cares about the people the regs are for. IG will run an investigation. PAO will write a release that isn’t a lie. We will not say ‘unfortunate.’ We will say, ‘unacceptable.’ And Shankar?” He looked the lawyer square in the eye. “You will write me a policy. New. Clear. With teeth. Reprisal gets you moved to the armory and keeps you there.”

“Yes, sir,” Shankar said.

Roth walked back toward headquarters. The heat had burned off a little. It wasn’t any cooler. It just hurt less.

Part IV — The Cost of Courage

You think the hard thing is the mess hall. It’s not. The hard thing is the Tuesday after, when everyone goes to work and tries to act normal. People watch themselves laugh to see if it sounds like betrayal. The rumor mill churns until its engine burns out. Everyone fails at least once—at the right pronoun, at the right tone, at the right time to look a person in the eye and say, “I missed it. I am sorry. I will do better.”

Clare spent the first week in the SARC office. She hated it. She was not built to sit in folding chairs under posters that told her she was brave. She needed tasks. Sergeant Major Harlan appeared one afternoon with a stack of paperwork.

“You’re coming to HQ for three months,” he said, voice a bass note that steadied the floor. “Brigade S-1 is a mess. We need someone with a brain.”

“Am I being punished?” she asked.

“No,” he said. “We’re protecting you. And using you where you can’t be punished. Your record’s flagged so no one can move you without this office knowing. If anyone gives you grief, you tell me and I’ll introduce them to a world of paperwork they didn’t know existed. You tracking?”

“Yes, sergeant major.”

He cleared his throat. “My daughter’s a captain,” he said gruffly. “She’s in intel. She sent me a screenshot of that climate assessment you took. She said, ‘For once, a man did the right thing without asking if it would look good.’ I told her to focus on her job.” He paused. “You keep doing yours. We’ll keep doing ours.”

She worked. She learned stupid arcana because stupid arcana was power: how to track a flag in eMilpo so it didn’t disappear when a commander ‘forgot’ to renew it, how to file a complaint in a way that triggered audits, what email subject lines got read. She watched men in pressed uniforms flinch when they had to walk into General Roth’s office and explain why a memo hadn’t been on his desk by the time he said it would be.

General Roth lived at his desk for a week. He signed things until his hand cramped and then switched to his left. He hosted an all-hands at the theater and stood on a stage and said the words that sound like an apology when a leader says them right. “This happened in my house,” he said. “On my watch. Shame on me. I can’t unmake the harm. I can build a different house.”

He laid out the new policy. Anonymous reporting lines. ROT shift changes to daylight for those under restriction. A guarantee that anyone who reported would never again be rated by the person they named. He included his own phone number on the slide. He took questions for an hour. He didn’t punt a single one to the SJA. He looked a young private in the eye when she said, “Sir, what if the person is a sergeant?” and said, “We will handle it,” and handed her a card with a captain’s personal cell.

When he walked off the stage, a chaplain caught his arm. “Sir,” he said. “You know the story in the book where Jesus flips tables?”

“I’ve flipped them,” Roth said, dry. “Did you see it?”

“I was there,” the chaplain said, smiling. “It was righteous.”

The base moved like a body learning to walk differently. There were missteps. A staff sergeant cracked a joke in a motor pool and found himself in a room with a command sergeant major who had run out of patience for clever cruelty twenty years ago. A PAO draft used ‘alleged’ in a way that made Lieutenant Colonel Shankar get out a red pen and draw a line through it so hard the paper tore. The line held.

Two months later, the court-martial convened. It ate two days of testimony and spit out a verdict: guilty on all counts. Doyle stood in dress blues that no longer fit him and heard the words that would be typed on a document that would follow him for the rest of his life. Dismissal from the service. Reduction to E-1 for forfeiture of pay. Six months in confinement. There was a statement from the bench about command misusing trust. There was a letter in the packet from a general who had learned late and wanted it on the record that he had learned.

Clare sat in the back row with Staff Sergeant Nguyen and a private she’d chosen to mentor because you pass it on or you fail. The bailiff called the court to order. The judge left. People stood. Doyle turned, eyes scanning the room for a face to harden against. He didn’t find Clare. She had already stood up, looked away, and left. Outside, the air felt lighter.

She still woke some nights to the sound of a ring on metal and dove out of bed before she remembered it was just a memory. She went running and burned it out. She went to therapy and learned to name it. She kept her notebook; she just started a new one. She taught a class to a junior NCO about how to annotate an Article 15 so it lives properly in a soldier’s packet and not in the drawer of a man who wants to buy a boat more than he wants to live with himself. She got selected for the promotion board on a packet no one could sabotage. She passed. Men who had once looked through her shook her hand.

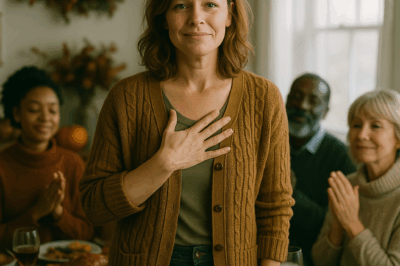

General Roth received a new star in a ceremony that made the newspaper. He pinned it on like it weighed fifteen years of work because it did. His wife—Charlotte, a former JAG—stood by his side with a small smile that had opinions. He thanked the usual people and then did something generals don’t usually do. He brought Sergeant Méndez to the front of the room, handed her an Army Commendation Medal, and said in front of everyone, “For courage beyond rank. For reminding us who we are. For forcing me to be worthy of this.” The room clapped. Some men clapped a beat too late because they were thinking about who they had been in the mess hall that morning.

Afterward, he found Clare in the hallway. “How’s the jaw?” he asked.

“It still twinges when I chew gum,” she said.

“You’ll find other vices,” he said. He hesitated. “Sergeant… I’m sorry. For the part I didn’t know about. For the part I should have.”

She shook her head. “Sir, you did the thing.”

“I did my job,” he said.

“You changed how it feels to wear this uniform,” she said. “That’s more than a job.”

He nodded once, like a man accepting a compliment that cost someone else too much not to.

Part V — Aftermath and Architecture

Fort Haven didn’t become perfect. No base ever is. Men still told jokes they thought were harmless that weren’t. Women still carried keys in their fists across parking lots at midnight. But the air in the mess hall changed. You could feel it in small ways—the way soldiers greeted each other, the way platoon sergeants paid attention at 2100, the way the door to the SARC office stayed open and people went in without looking left and right first.

Word spread across the Corps because word always does: Fort Haven doesn’t cover things. A case in Bravo Company went straight to CID in forty-eight hours. A warrant officer who thought a junior couldn’t say no found himself rehearsing answers with a defense attorney instead of a class. The post barber put up a sign that read IF YOU SEE SOMETHING, SAY IT LOUD.

At the next change of command, Roth stood in dress blues that fit him like a plan and handed a guidon to a colonel who had been a captain with him back when they wore woodland cammies and watched the world map go strange. He said the right words about stewardship and standards. And then he paused. He looked out at the formation—rows of soldiers in the kind of heat that makes your eyes feel dry—and said, “There is a way the Army hides behind how we’ve always done it. That ends where I stand.”

He handed the microphone to a staff sergeant from S-1—Clare, hair neat, ribbon rack honest. She didn’t give a prepared speech. She told them two stories: the mess hall, and a day in the corridor after the hearing when a private knocked on her office door and asked if she had a minute, and she did, and the private told her a thing she had never told anyone, and they went together to the SARC office, and the private filed a report, and nothing bad happened afterward except the thing that was supposed to happen to the man who had hurt her.

“This is what standing up looks like,” she said. “It’s not dramatic. It’s paperwork and walking someone down a hallway. It’s all of us changing how we talk in rooms we used to feel safe in. It’s boring. It’s brave.”

People didn’t cheer. They breathed.

Roth watched her step off the stage without tripping. He felt his phone buzz in his pocket and ignored it because this moment was more important than whatever the Pentagon wanted. The chaplain leaned over and whispered, “You’re getting soft in your old age, sir.”

Roth smiled without breaking the line of his shoulders. “No,” he said. “I’m getting right.”

In the mess hall, months later, a new lieutenant walked in with a tray and a grin he thought made him bulletproof and saw a staff sergeant with a bruise on her cheek from a fall on a ruck—real this time—laughing with her squad, and he opened his mouth to say something about toughening up and then remembered the story every soldier at Fort Haven knew and didn’t. He closed his mouth. He picked up a chair. He put it down; he sat. That small thing saved someone a drop of rage they would have had to burn off later.

General Roth retired a year after his third star. The ceremony was clean, no pageantry he hadn’t earned. He stood at the microphone and didn’t talk about campaigns or ribbons. He told them a story about a morning in a mess hall when a room went quiet and he found out who he was. “I am not proud that I didn’t see it sooner,” he said. “I am grateful I was given the chance to do something about it when I could.” He looked at Clare where she stood in the back in her service uniform, jawline unbowed. “You don’t need space to be brave,” he said. “Sometimes you just need a table to hit.”

After it was over, he walked outside into a light that caught the flag and pulled it toward the sky. He pulled his cap low against the glare and stepped off the stage to a ground he had earned and that had been waiting for him all along.

Clare returned to her unit. She heard a private whisper to another, “That’s Sergeant Méndez,” and didn’t flinch. She ran a range that finished on time and under budget and qualified eight of ten on Expert. She went home that night to a small off-post apartment that smelled like laundry and dog and the lemon oil she used on the thrift-store table that had become her command center. She set her cover on the peg on the wall, the way her grandfather had taught her to take care of your tools. She looked at her face in the mirror—not at the fading edge of yellow on her cheek, but at her own eyes.

She pulled a notebook from her pocket and wrote two lines on the last page: Justice isn’t loud. It’s architecture. You build it so the next person has somewhere to stand.

She closed the book. She slept.

And at Fort Haven, long after midnight chow, a sergeant on CQ looked up from a logbook and saw Captain Doyle’s name and drew a line through it with a steadiness that said we’re done with that now. Outside, the air cooled. In the morning, the flag would rise again. Men would laugh and women would lace boots and generals would drink coffee that tasted like burned hope. Someone would ask a question in a cafeteria and get an answer they didn’t expect.

And the room would freeze—not because fear had entered it, but because justice had.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

They Called Me a Fraud in Court — Until the Judge Whispered, “Commander, You’re Clear to Proceed ”

They Called Me a Fraud in Court — Until the Judge Whispered, “Commander, You’re Clear to Proceed ” Part I…

SEAL Jokingly Asked For Her Rank, Until Her Reply Made the Entire Cafeteria Freeze

SEAL Jokingly Asked For Her Rank, Until Her Reply Made the Entire Cafeteria Freeze Part I — Dust, Heat,…

My Family Cut Me Out of Thanksgiving — So I Invited Everyone They Ignored.

My Family Cut Me Out of Thanksgiving — So I Invited Everyone They Ignored Part I — The Uninvite The…

My Grandma Left Me Her $50M Hotel Empire, But Mom’s New Husband Took Control, Then Grandma Did This

My Grandma Left Me Her $50M Hotel Empire, But Mom’s New Husband Took Control, Then Grandma Did This Part I…

Mom Texted,We’ll Miss Your Son Birthday Things Are Tight Right Now. Said, That’s okay.The Next Morning

Mom Texted, “We’ll Miss Your Son’s Birthday — Things Are Tight Right Now.” I Said, “That’s okay.” The Next Morning,…

After My Accident Dad Texted Can’t This Wait We’re Busy Three Weeks Later I With Some Papers…

After My Accident Dad Texted “Can’t This Wait? We’re Busy.” Three Weeks Later I Showed Up With Some Papers… …

End of content

No more pages to load