Found My Elderly Parents Frozen Outside My Own House While In-Laws Celebrated Inside Like They Owned It All — What I Did Next Destroyed Their Lives Completely

Part One

Nothing about the evening hinted at disaster. The sky over Lakeview Drive was a cold sheet of pewter; a few stray leaves rattled across our walk like coins. I’d just finished setting the last spoon on the dessert table when the doorbell rang—one polite chime swallowed by laughter and jazz from the living room. Through the bevelled glass I could see silhouettes moving in that practiced, ornamental way my mother-in-law adored—flutes level with cheekbones, a hand to a lapel, the inclination of a head that telegraphed, I understand the right forks.

I slipped past a server with a tray of mini lobster rolls I had not ordered and called, “I’ll get it.” No one heard me. Of course they didn’t. When Nancy hosted—even in my house—everyone else became part of the set dressing.

The lock caught and wouldn’t give. I frowned, jiggled the key, tried again. It didn’t fit.

“Robert?” I said over my shoulder. “Did you have the locks—” No answer. He was in the middle of his best impression of a man born to schmooze, laughing in exactly the right place at Walter’s joke, one hand on the back of a senator’s aide as if they were old summer friends.

My phone buzzed. We’re here, sweetheart. My mother. I looked through the glass again, past the reflections of rented candles and ridiculous orchids. Two figures stood on the porch: my father in his camel coat with the collar turned up, my mother’s hand in the crook of his arm. They were too thin for the cold that had swept in at sunset, and my father’s cheeks showed the gray undertone I recognized from the weeks after his bypass.

I tried the handle again. Nothing. “Excuse me,” I told no one in particular, then hurried around the side of the house. In the kitchen, a young man in black moved with the flitting efficiency of a moth. “Back door only,” he said without looking up. “All guests enter at the side.”

“I live here,” I replied. He glanced at me then—down my black slacks and cream blouse, not evening enough for Nancy’s taste, then back to his tray.

“Entrance is out front,” he repeated. “This is for caterers.”

“Peggy.” From the far end of the room, Nancy appeared, her voice the clink of expensive ice in cut crystal. She wore white in November because she liked rules best when breaking them. “The governor’s aide just arrived. You’ll want to say hello.”

“The front door is locked,” I said. “My key doesn’t work.”

“Robert had security upgraded,” she said, as if I’d asked about napkin rings. She reached for a fig from a cheese board I hadn’t ordered. “Lovely spread. Much improved.”

“My parents are outside,” I said. “In the cold.”

Her mouth softened—but not with compassion, with disdain disguised as sympathy. “We’ll seat them when we’re finished with the first course.”

“They can’t wait,” I said, pushing past her toward the refrigerator. My father’s heart meds were behind a silver platter of quail eggs. My mother’s arthritis pack had been pushed to the back to make space for rent-by-the-hour caviar.

I made it back to the front in time to hear my father pretend not to wheeze. “Traffic,” he said. The porch light chalked the blue of my mother’s lips. My father’s hand trembled in mine, his fingers colder than they should have been after three minutes in November, let alone thirty.

The key stuck uselessly in the lock. I knocked hard and rang again. People glanced up from inside—eyes cut sideways, shoulders not quite turning. I could see my couch in profile against the opposite wall—moved to make room for cocktail tables I had not sanctioned, family photos I’d hung taken down to make space for florals that smelt faintly of debt.

“Back entrance is—” A server had opened the side door an inch to let in air. I didn’t let him finish. “This is my house,” I said. He stepped back. I helped my father in, the heat hitting us like red cheeks. My mother’s knees buckled and I guided her toward the couch, easing her down with the slowness her joints required.

Conversation deflated in the room like an under-inflated balloon, first sag, then silence. Everyone was suddenly looking everywhere but at my parents, whose breath condensed in quick prayers.

Nancy arrived with the smile she kept for photographers. “We’re in the middle of a toast.”

“My father needs his medication,” I said, swallowing all the words that burned harder than the turn of the key had. “And a chair with support.”

“You are making a scene,” she replied under her breath. Over her shoulder I saw my husband—the man who had vowed to put me first—look at me and then look away.

An ambulance wailed into the night bright as judgment. When the paramedics threaded their way through a corridor of men with cufflinks, Nancy hissed, “Not in the living room.”

“Where would you like them to resuscitate him?” I asked. “The pantry?”

The EMT’s hands were quick and competent, their questions the kind that mean business: “How long outside? History? Meds?” My mother answered while I balanced my father’s pill bottle in fingers that had started to shake.

“It’s cold in here,” Walter said loudly, looking not at the man in distress but at his martini. “Someone tell the caterer to adjust the heat lamps.”

They took my father out through the front and into the flashing lights. I went with him. My mother gripped my wrist the way she had when I was afraid of dogs at age six.

In the ER, the words came fast: hypothermic, strain, observe overnight. I watched my father’s color warm from ash to the pale pink of the hospital blanket. My mother’s shivering slowed, then stopped. When I finally sat down, my phone buzzed with a message from Robert: Are you coming home?

I looked at the wall clock—straighter than any line I had walked that night—and texted back: Don’t be there when I get home tomorrow.

There was a pause long enough to be hope. Then: Be reasonable. You know they meant well.

That was the first moment I understood we had moved beyond repair. Not because the locks had been changed or because senators laughed at the wrong jokes. Because he could not tell the difference between intention and harm.

Vanessa, who knew me before Nancy learned my middle name, met me at the hospital with a sweater and a legal pad. She was a family attorney, which men like Walter call vocational feminism when they think I won’t tell Vanessa. “You own seventy percent of that house,” she said, her hand steady on mine. “We’re not going to fight in their kitchen. We’re going to court.”

By noon the next day, a locksmith was changing every lock in my home while a police officer stood by to keep Walter from making a point with his finger. I found Nancy’s toiletries lined up in my guest bath like soldiers reporting for duty and a folder in Robert’s office labeled House Modifications. Inside were sketches turning the ADA-friendly suite I had chosen for my parents into a library with a scotch bar, a draft change-of-address for Nancy and Walter Cunningham, and a contractor estimate with a start date the week of our housewarming. The line items looked like theft wearing pearls.

I photographed everything and printed two copies: one for Vanessa, one for my bones.

The meeting at Vanessa’s office felt like putting a lit match to a pile of leaves that had been damp too long. Walter arrived with a tie tight enough to cut off circulation to good judgment. Nancy wore a silk scarf the color of money. Robert looked like the son of both.

“Family matters should be handled in the family,” Walter said by way of hello.

Vanessa’s smile was both sweet and surgical. “We agree. But legal matters belong in legal offices.”

I presented the facts as if I were pitching a client: date of lock change; number of unauthorized guests; documented cash withdrawals—$40,000 in three days—caterer invoices addressed not to me or Robert but to Walter Cunningham; medical bills with words like cardiac strain precipitated by exposure. There is a tone some people use to minimize harm. Vanessa knows it, and cut it off with the phrase that rearranged the room: “Potential elder endangerment.”

Something flickered across Nancy’s face that I had not seen before. Not guilt—she would not grant herself the discomfort—but calculation. “We will cover any expenses,” she said quickly.

“No,” Vanessa replied. “You will reimburse the joint account in full for funds misappropriated, enter into a no-modification agreement without both signatures, and agree in writing that you will never change locks or security codes again without written consent from both owners. You will not host, invite, or allow guests into the home without Peggy’s explicit consent, and all prior copies of keys will be returned today. Future visits will be pre-approved, scheduled, and limited.”

Walter bristled. “This is extortion.”

“This is accountability,” Vanessa said, and slid a settlement proposal across the table.

Robert swallowed. His hands—those clever hands that could close a deal in an elevator—shook. “Mother. Dad,” he said quietly. “Sign it.”

Nancy turned on him with all the cold that had made him who he was. “Robert, darling—”

“Sign it,” he repeated. For a second, the room held three decades: the child, the teenager, the man. I watched him choose. In that moment, I didn’t forgive him. I did feel something like pity for a boy taught that approval was currency.

They signed. We changed the locks again after they left.

That night, I sat at my dining room table with my parents and watched my father eat soup that we both salted to his taste. My mother’s hands warmed around a cup of tea the way hands do when held. Outside, the neighborhood was very quiet.

Part Two

The apology came on the third Tuesday of the month with a cake that clearly came from a store Nancy pretended didn’t exist. “For what it’s worth,” she said, civil as a ceasefire. “We… miscalculated.” It was meant to sound magnanimous. It sounded like a woman who’d learned the word elder endangerment has a long reach in communities with boards and gala committees.

Robert started therapy because our lawyer wrote it into the settlement as if it were a bathroom addition: necessary and not optional. The first week he came home with a vocabulary he used like talismans: enmeshment, triangulation, boundaries. The second week he admitted, quietly, in a kitchen without caterers, that he didn’t know what he wanted beyond not disappointing the couple who had taught him disappointment was punishment. The third week he asked if it was too late to become his own person.

“I don’t know,” I said. Honest because it was the only thing left. “I’m becoming mine.”

We separated, amicably the way you call a storm amicable once it’s done and you’re standing in new light. Vanessa drew up a postnuptial agreement with teeth that glittered even in fluorescent glare. The house deed included a clause that would make Nancy’s eye twitch if she ever read it: No party shall host or permit any event of more than twelve people without written agreement of both parties. I printed that sentence on expensive paper and framed it above my desk because sometimes petty is medicinal.

Robert paid back every cent, apologized to my parents (my mother accepted with grace, my father with a grunt, which is grace in his dialect), and paid the hospital bills straight from his account in front of me without a call to Walter. He asked if I would consider rebuilding. “Maybe,” I said. “From a blueprint we both design this time.”

The blueprints of my revenge didn’t involve destruction. They involved daylight.

I sent formal letters to the boards Nancy served on, including the Community Arts Alliance and the St. David’s Hospital Foundation, documenting the evening, the medical outcome, and the steps taken since. I included the phrase elder endangerment risk not because I craved drama but because accuracy matters. St. David’s accepted her resignation the next day. The Arts Alliance made hers “effective at the end of the term,” which meant the season’s gala committee suddenly lost interest in her suggestions. Once, years from now, Nancy will remember that evening in my living room as the beginning of her social quieting, and she will never tell anyone why.

I met with the HOA and rewrote rules. Not the petty ones about mailbox heights—though those got tidied up, too—but the clauses that protect homeowners from having rentals masquerading as “events” turn a home into a banquet hall. The board had never contemplated a valet line on our street. They have now.

I returned the rental furniture and redecorated. Not out of spite. Because there is relief in putting your couch where it belongs. I hung our family photos back on the wall, including the one of my father on the porch step with a blanket over his knees looking like stubbornness had a face and it belonged to us. When I put the frame down, I cried and didn’t pretend it was only about wallpaper.

I hired an accessibility consultant and had the guest suite evaluated properly. The new grab bars no longer look like a concession but like the kind of love that thinks ahead. The door hardware now opens with an elbow if my mother’s hands are stiff. The rug pad doesn’t slip. This is how you build a life that won’t betray you when you aren’t looking.

I had the locks re-keyed one more time and bought a small key safe for my parents’ copies. The combination is the year they eloped—a number that has held us all longer than any settlement clause.

I told my mother, gently, about boundaries. I told my father that he is allowed to say no to a son-in-law. He did, once, over a matter as small as the placement of the liquor. It was excellent practice.

I invited Robert’s sister, Claire, to coffee. She held her latte with both hands and told me stories that were too familiar: the way Nancy had stood at the foot of her hospital bed after a C-section and told the nurse, “We’ll be taking the baby to our house for a few weeks so Claire can rest properly,” as if kidnapping were a favor. The way Walter had “just known” the right school for their kindergarten and moved two streets over without asking. We laughed in the awful way women do when finding out their pain has a twin. “You made it stop,” she said. “They hate you for it. Thank you.”

I wrote thank-you notes to the EMTs and to the neighbor who brought the blanket and to Vanessa because lawyers do not receive enough flowers for keeping people alive in the parts of the world without IVs. I baked a pie for the firehouse, which I burned because justice does not improve your crust, then bought a pie and put my pie in the trash in a ceremony that made me feel like a person again.

The $22,000 catering bill arrived with a note that said, “We trust there will be no dispute.” Walter’s signature was so big it thought it could summon gravity. Vanessa wrote back: “This invoice appears to have been addressed to the wrong party. Please forward to Mr. and Mrs. Walter Cunningham.” It was the legal equivalent of sending a meal back with lipstick on the glass.

In February, my father walked up my front steps without pausing to breathe midway. In March, my mother asked if she could bring the green beans because she hated my recipe. I said yes and didn’t pout because love looks like letting the matriarch win on vegetables.

On a bright Saturday in April, Robert and I sat on the porch while the maple that didn’t die clattered softly in a breeze. “I’m selling my shares and starting my own firm,” he said without preamble. “No more boardrooms full of men who like my mother too much.”

“Good,” I said, and meant it. We were not yet together. We were adjacent. It was enough.

Community gossip moved on because it always does. Our story became a cautionary tale told quietly at committees and loudly at salons, a fable with interchangeable in-laws and interchangeable daughters. Sometimes that stung—the reduction of what had almost killed my father to a lesson in seating charts. Mostly it felt like a public service. Let the story work for us when our feet are tired.

By summer, we held a new party. Not a housewarming. A thank-you. No valets, no orchids, no senators. Friends brought folding chairs and cut-glass bowls from their childhood kitchens. My father grilled and insisted his cardiologist would understand. My mother took off her shoes beneath the table and said, “This feels like before and after at the same time.” Nancy was not invited. Walter sent a bottle with a card that said Wishing you all the best in your new chapter. I used it to prop open the screen door and drank the Riesling a week later on the porch with Grandma because redemption is odd and sweet.

A year later, a young woman from my team knocked on my office door and said, “Can I ask you something not about work?” She told me about a fiancé whose mother believes boundaries are for people without vision. I told her what Vanessa told me: “Get all decisions in writing. Don’t argue in kitchens. Keep your name on the deed.” I told her what I told myself: “There is a difference between setting a table and laying yourself down on it.”

When the leaves turned again, my father and I sat in cardiology waiting for his six-month check. He read a magazine like it might confess something. “You did good,” he said without looking up. It is not his language. It is enough.

On the drive home, my phone flashed a message from Robert: Therapy at four. Don’t forget. He was still doing it even when there was nothing left to salvage except himself. I respected that. Sometimes, when I am generous, I admire it.

We are not a movie with a bow. The lives I “destroyed completely” were not bodies in ruins; they were illusions: Nancy’s belief that power is hers by right; Walter’s conviction that rooms belong to the loudest check; Robert’s faith that disappointing his parents will kill him. The destruction was not revenge. It was renovation.

Once, when I was eight, I helped my father take down a wall in our old ranch house to make a room bigger. Halfway through, a support beam bowed. He put his hands on it and said, to the wood or to me or to nobody, “It’s not enough to knock down what hurts you. You have to put something sturdy in its place.”

This is my sturdy: locks that click for the right keys; a guest suite built for the bodies I love; a living room that makes room for truth; a marriage that became two honest lives; a mother-in-law learning that humiliation echoes louder than applause; a father who knows now that my house is safe; a mother who warms her hands without fear; a grandmother who still calls after dark.

Last week, Nancy sent a text that said simply, We’re moving to Palm Beach. I wrote back, Safe travels.

When I walked my parents to their car on Sunday, my mother kissed my cheek and said, “You have your grandmother’s spine.” I laughed because Grandma would call that a compliment. “No,” I said, glancing at the maple. “I have her stubborn.”

“Same thing,” my father said, which, for once, felt like family.

If you ever find your elderly parents shivering on your porch while someone else throws a party in your living room, this is what you do: you let the ambulance paint your night with necessary color; you call a woman like Vanessa; you change the locks; you write the letters with the words that matter; you choose a life in which your living room belongs to your love and your porch light is never off.

And when you hear laughter from inside that does not include you, you bring the people you love inside, you warm their hands, and you light your own house properly.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

My daughter-in-law slapped me in the face and demanded my house keys! CH2

My Daughter-in-Law Slapped Me in the Face and Demanded My House Keys! Part One The slap landed before I…

My Husband Thought I Faked My Pregnancy, Then Pushed Me Down The Stairs To Test — My Sister Laughing. CH2

My Husband Thought I Faked My Pregnancy, Then Pushed Me Down The Stairs To Test — My Sister Laughing …

My Parents Watched My Sister Push Me Down The Stairs. The Hospital Security Camera Caught Everything. CH2

My Parents Watched My Sister Push Me Down the Stairs. The Hospital Security Camera Caught Everything Part One My…

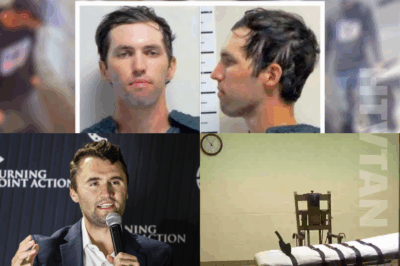

Suspect In Charlie Kirk Killing Could Face The DEATH PENALTY — Utah Signals An AGGRAVATED Murder Case

Prosecutors booked 22-year-old Tyler Robinson on aggravated murder, a charge that opens the door to capital punishment under state law….

“We will find you, we will try you and we will hold you accountable to the furthest extent of the law. And I just want to remind people we still have the death penalty here in the state of Utah.”

Utah Governor Spencer Cox Issues STARK WARNING — State STILL Has The DEATH PENALTY As The Charlie Kirk Case IntensifiesHours…

SIGN THE DIVORCE PAPERS OR I’LL BREAK YOUR NOSE MY WIFE’S NEW BOYFRIEND, A GANGSTER, THREW THE PEN AT ME “YOUR CHILDREN ARE MINE.”

“SIGN THE DIVORCE PAPERS OR I’LL BREAK YOUR NOSE” MY WIFE’S NEW BOYFRIEND, A GANGSTER, THREW THE PEN AT ME—‘YOUR…

End of content

No more pages to load