Father banned me from my own FIVE-STAR HOTEL, So I told SECURITY to REVOKE their VIP ACCESS

Part 1

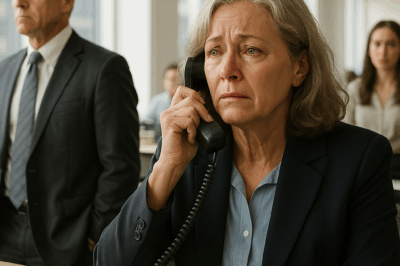

The text came in just after noon while I was on a video call with architects about our Paris expansion.

Don’t come to the wedding, Morgan. It’ll be better for everyone.

Nothing else. No context, no apology. The wedding, of course, was at the Marston in Boston—my flagship, the property that put the Wellington Collection on the map. The one with the Italian marble floors I argued for when value engineers rolled their eyes. The one whose rooftop garden I insisted could carry a small orchestra without rattling the glass. My hotel.

I stared at the message and let out the kind of laugh that sounds more like a cracked plate than a joke. They didn’t know. Of course they didn’t. They had never asked what exactly I’d been building; “hotels” was a hazy category in their minds, beneath Wellington ambitions. I set the phone face-down and looked through the glass wall of my office to the city beyond—cranes stitching skyline, a blue so sharp it looked recent. I turned the phone over again and opened our security group thread.

Wellington family no longer VIP. Pull comps. Standard service only.

Send.

My name’s Morgan Wellington. I’m thirty-four. I split my time between Boston and New York. I grew up in Wellesley where being a Wellington was supposed to mean something; in our house, it meant law degrees like inheritance and dinner conversations that sounded like depositions. My father, Harold, could quote obscure precedent like scripture and make you feel uncivilized for breathing wrong. My mother, Diana, cataloged social hierarchies the way ornithologists catalog birds—quietly, meticulously, with judgment disguised as curiosity. Emotions were for people without options. Hospitality, in their minds, was for people who didn’t choose well enough.

When I told them I wanted to work in hotels, they treated it like I’d announced I wanted to juggle torches on a street corner.

“You’re a Wellington,” my father said. “Act like it.”

Funny thing: I thought I was. Every 2 a.m. guest issue I solved at a front desk, every burst pipe I triaged before sunrise, every disastrous check-in I turned into a five-star review felt like the best version of the name—competence, accountability, service without condescension. Not their version, but a better one.

The obsession started early. Other kids collected baseball cards; I pocketed plastic room keys. I watched bell staff orchestrate lobbies like ballet. I learned how a good concierge could fix a flight, a fight, and a proposal with the same soft tone and a Rolodex you’d sell your car for. It didn’t feel glamorous. It felt alive.

I applied to Cornell’s Hotel School in secret. Wrote essays under a blanket with a flashlight as if I were confessing to a crime. When the acceptance letter came, I waited till dinner to say it.

“I got into Cornell’s School of Hotel Administration,” I told the table, hands shaking under the wood.

My father didn’t look up from his plate. “Not what we discussed.”

“I’m not going to law school,” I said, and felt something unclench in my chest just from fitting the words together out loud.

He set his fork down then, finally met my eyes. “Then I guess you’re on your own.”

I took him at his word. Bused tables at the Newton country club, slung pancakes at a Route 9 diner, shoveled mulch for cash, stacked loans on loans. They barely called; when they did, it sounded like someone checking in on a roommate from a summer program. During my freshman year my brother, Brandon, got into Columbia Law. My parents threw a catered party with a cake in the shape of the skyline. When I graduated, they went to Brandon’s ceremony in the city the same weekend and never mentioned the conflict. I found out through a cousin’s Instagram. I walked across a stage in Ithaca and scanned the stands like an idiot anyway. Later I sat alone at a bar with my diploma in my bag and a shot of well whiskey, made a quiet promise that didn’t need words: One day you’ll walk into a hotel and never realize it’s mine, because you never cared to look at me closely enough to know.

Two weeks later I moved into a Midtown studio I shared with two other Cornell grads. The apartment was a humid shoebox with one working stove burner and a shower so small your elbows learned humility. It didn’t matter. I had my first job: front desk at the Marrow, a boutique wedged between two banks and a juice bar on East 45th. No brand halo, one elevator with attitude, a general manager who gave a damn.

I took every shift—overnight, doubles, holidays with a bow on them. I watched, wrote notes, ran the night audit even when it wasn’t mine, memorized reservation pathways until the back of house felt like a map I could fold with my eyes closed. I built a spreadsheet of guest complaints—color-coded, categorized, resolved with receipts. A honeymoon couple assigned a smoking room? Move them, comp the view, send chilled champagne and a handwritten note. A frequent business guest without luggage before a morning keynote? Walk to H&M, buy a white shirt and a tie on my own card, steam them in back of house, hang them on his door with a wake-up call set. He left a five-star review the next day and copied the GM. Suddenly I wasn’t invisible.

Six months in, Katherine Reynolds—regional director, sharp bob and a pen on her lapel like a tiny sword—watched me check in four guests without breaking stride. “You ever think about management?” she asked afterward.

“I think about making rent,” I said. She laughed. “Fair. If you’re serious, I’ll keep an eye on you.”

She did. A year later she called: Want to fix something on fire? The Chicago property was drowning. I said yes before she finished the sentence. I slept in housekeeping my first week and wrote standard operating procedures at 3 a.m. on a folding table. I trained nights, fired three managers, rehired two of them for different roles, learned that the fastest way to turn a hotel is to make the staff believe you see them. Six months later we were breaking even. Katherine pushed for my assistant GM title. I called my father, because old habits die like trees: slowly, loudly, reluctantly.

“I’m assistant manager now,” I said. “Chicago.”

He chuckled. “Still playing hotel, huh?”

I sat on the floor of my closet and let the sound leave me like air from a punctured tire. Then I changed shirts and ran back downstairs. Night audit didn’t care.

Promotions compounded. At twenty-six I was running three properties under Katherine’s region. At twenty-seven I found a wreck in Providence: water stains like maps on the ceilings, a lobby that smelled like bleach and defeat, a roof that apologized when it rained. The owner was desperate; I brought a deck, a plan, and a stubborn face. He said yes. I named it The Wellington. Not for them. For me. To reroute the word.

I lived in a stripped staff room with a space heater that knocked out the power every third hour. Folded towels, unclogged drains, rewired a light switch with YouTube on mute, learned more about boilers than any Cornell class could have taught me. Reviews crawled from two stars to four. We booked weekends. We turned a corner.

Katherine introduced me to money. I had spreadsheets with early wins, a playbook scarred with mistakes, a vocabulary investors liked. The first round closed in six weeks; I stopped sleeping twice a week and called it balance. At twenty-nine we had twelve properties. Guests started asking if we were a chain. “Not yet,” I said, and meant it.

The industry handed me a glass plaque at a black-tie dinner: Emerging Hospitality Leader of the Year. I didn’t invite my family. They came anyway, late. They sat in the back and didn’t clap. I found them after.

“Didn’t expect to see you,” I said.

“We had a free night,” my father said. “Figured we’d check it out.”

“You built all this yourself?” my mother asked, scanning the ceiling like she’d never been under one before.

“Yeah.”

“Is there real money in it?” he asked. “Long-term?”

I walked back to my table and ate a dessert I didn’t taste. Katherine put a hand on my shoulder that said everything without moving air. After that night, I stopped sending updates. The buildings were enough conversation for anyone who wanted to look.

And then my sister Jess texted about the wedding.

Just booked some hotel in Boston. The Marston looks super nice!

“Some hotel.” I stared at the message and didn’t tell her. Let the work introduce itself.

They toured on a Friday. I watched from my office on the operations feed: four camera angles, clear audio. Erica, our sales manager, did the tour I hired her for—brisk, warm, factual. My mother trailed her with a leather planner she held like a shield. My father walked ten steps behind, hands clasped behind his back like he was inspecting a courtroom.

“This carpet feels… a little dated,” my mother said.

“Is there valet or just that weird loop outside?” my father asked.

Erica smiled like only Erica can, wrote things down she didn’t need to write, offered two options better than the one they wanted. I comped the best suite, upgraded the block, added the elite wedding package—champagne tower, quartet, rooftop photos at sunset. No note. No signature. Just the machinery of service doing what it does when the purpose is clean.

Rehearsal night, my floor supervisor pinged me: Guest issue in the wine room. I went down. I heard his voice before I saw him.

“Are you kidding me?” my father barked. “I said Napa, not Merlot.”

Our sommelier—twenty-one maybe, hands careful on a bottle—stood there like someone had pulled a fire alarm behind his ribs.

“Everything all right?” I asked.

My father turned, squinted. Didn’t register me at first. “This server doesn’t know the difference between a cabernet and a juice box.”

“Sommelier,” I said. “He’s not a server. And he’s doing his job.”

The room changed temperature. People started looking at their napkins.

“I don’t know who you think you are,” he said, “but stay out of this.”

“I am in this.” I gave our sommelier a nod. “You’re fine. Table five needs you.” He exhaled like a diver breaking surface and slipped past us.

My father left without another word, muttering something to my mother that made her lips flatten into a line.

By morning, the team ran on adrenaline and espresso shots. Florals late. Housekeeping a room behind. The lighting crew couldn’t find the control tablet. I watched it all and then watched something else: my father on the ballroom floor with a clipboard he had confiscated from someone’s hand, moving reserved signs like he owned the alphabet.

“Conference room prep, penthouse suite, fifteen minutes. Full exec team,” I told my GM. “And bring the Wellingtons.”

We gathered around the long walnut table in the suite. My GM, my director of ops, security, F&B. Katherine had flown in and stood in the corner like a judge I’d actually choose. The elevator dinged; my parents stepped in as if cameras were waiting.

“What is this?” my father asked.

“I wanted to clarify a few things before the ceremony,” I said. I looked at my team first. “You all know who I am.” Then I looked at my parents. “They don’t.”

“This is my company,” I said. “The Wellington Collection. Fifteen properties—including this one.”

My mother’s mouth parted just enough to ruin her lipstick. My father stared the way people stare at paintings they don’t know how to price.

“You’re joking,” he said.

“No. Every square inch of this place has my fingerprints or the fingerprints of people I hired. I signed the contracts. I negotiated the rates. I chose the marble you walked over when you complained about the valet loop. The sommelier you humiliated? I recruited him out of school.”

Jess came in then by accident, in a robe, hair half-pinned. She froze, looked from me to them, then back.

“What’s going on?”

I didn’t take my eyes off our father. “I own this hotel,” I said. “I built this collection.”

Jess blinked. “Wait—this is yours?”

“Every inch.”

My father exhaled like a man negotiating with gravity. “Well then,” he said, as if the room were a chessboard and he’d just seen a move he could use, “since it’s staying in the family—how about the Wellington discount?”

I laughed. A short sound. Sharp. “You still don’t get it,” I said. “You’re not family here. You’re guests. That’s how you’ve always treated me—like a stranger at your table. You insult my staff, rearrange my ballroom, and still expect me to comp your vision.”

I turned to my team. “As of now: revoke all Wellington comps. Strip the upgrades. Standard rates. Standard keys.”

My mother paled. Jess looked like she wanted to build a bridge with her hands and didn’t know where to place it.

“We’re your family,” my father said, low.

“Then act like it,” I said. “Or stop expecting treatment.”

I left before anyone could rehearse a rebuttal.

In the operations hub, I gave the order again, calm, clear. No one flinched. That’s what I had built: a team that trusted my judgment even when it hurt to watch me make the call.

In my office, the screens told a movie: the ballroom bright as a magazine spread, Jess radiant, my mother vibrating in pearl, my father with a face he reserves for juries. At 9:43 the front desk rang.

“Mr. Wellington’s card isn’t working,” the night manager said. “He’s demanding to speak with someone.”

“Patch him through,” I said.

“You’ve locked us out of our room,” he snapped. “Fix it.”

“You’ve been reclassified as standard guests,” I said. “Policy applies.”

“You little—” He stopped himself, swallowed. “You want to do this now? At your sister’s wedding?”

“You already did,” I said, and hung up.

I watched the night manager walk him through the polite version of consequences: new keys, ID required, a smile that didn’t move beyond muscle memory. He handed over his license because he had to. He took the keys because he had fewer choices than he liked to admit. For the first time, I saw him as any other guest—the way our system saw him: a name, a room, a rate. Justice tasted like metal. Victory didn’t.

Guests clinked glasses. The band found a groove and stayed in it. Jess looked stunning and tired, happy and wary, luminous and a little alone. She kept glancing toward the door. I stayed in the office with two fingers of bourbon, not because I wanted it but because my hands needed something to hold that wasn’t a decision.

I didn’t sleep much the week after. I didn’t answer calls I didn’t have the capacity to handle. I recalibrated budgets that didn’t need recalibrating and pretended the numbers required me more than I required air.

On day seven, Katherine walked in without knocking. She slid into the chair across from me and said, “You look like hell.”

“I’m busy,” I said to a spreadsheet.

She folded her arms. “You built this whole thing to prove yourself.”

I laughed. “And?”

“And it worked.” She tilted her head. “At what cost?”

The sob came out of me like someone finding a fault line with a hammer. Head in hands, elbows on desk, an embarrassing, honest sound. Katherine didn’t lecture. She didn’t touch me. She left the door closed and the room quiet and stayed until my breath remembered how to be a person.

The next morning I booked a therapy consult. No corporate discount. I talked about the ridiculous and the necessary: room keys I still keep in a box; the way my father’s laughter feels like lint you can’t stop finding; the certainty that I would rather lose a building than my people. On week three, I texted Jess.

If you ever want to talk, I’m here.

She called the next night. “Why didn’t you tell me?” she asked. No accusation. Just ache.

“Would it have changed anything?” I asked.

A long pause. “Maybe. I don’t know.”

We met for coffee and talked like siblings who used to fight over cereal prizes. She apologized for the way the rehearsal went. I told her I was proud of her for managing a hurricane with grace. It wasn’t everything. It was a start.

Two days later, an email from my mother dropped into my inbox: WSJ article. The Journal had run a piece on our Paris opening with a photo I didn’t hate.

We didn’t know. We never saw how far you took this. Maybe that’s on us.

I stared at it for five minutes. Then I typed: Maybe that can change. Send.

Three months later, I invited them to Paris. Not for a milestone. For an opening. I booked them a client itinerary—airport pickup, early check-in, restaurant reservations. In the marble lobby off Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, I met them without a script.

I gave them the tour I gave LLPs and hedge funds: rooftop terrace where the city looks like it dressed up for you, suites that smell faintly of cedar and possibility, a spa level with heated floors that make even skeptics slip off their shoes, a kitchen that sounds like precision. For once, they were quiet. My mother touched a velvet headboard like it might bruise. My father didn’t ask about margins. He looked.

“This is impressive,” he said.

Two words, late enough to double as a question. I didn’t give him more than he offered. “Thanks.”

We ate dinner at the rooftop restaurant. No legal talk. No politics. No performances. The next morning Jess FaceTimed from Boston, a newborn on her chest.

“She came early,” she said, smiling so wide the camera struggled to frame it.

“Everyone okay?”

“Perfect.” She paused. “I want you to be her godfather.”

No award had ever landed that deep. “Yes,” I said, voice chasing itself. “Of course.”

Something shifted after that. I started showing up in ways that didn’t require buildings. I launched a mentorship pilot for people who reminded me of me at twenty-two: night-shifters, couch-sleepers, spreadsheet-makers, problem-finders with no one to hand them a flashlight. No Ivy filter. No last-name test. Grit and a pitch. I mentored the first three myself. One of them—Tyrell—called the night his occupancy hit a hundred percent.

“I did it,” he said, breathless.

“You always could,” I replied.

Every win loosened something I’d cinched too tight for too long. I had built an empire to prove something. Teaching other people to build theirs showed me the thing I’d actually been trying to prove: that I could be the person I needed and never had. The buildings were byproducts. The work was people.

Part 2

A year to the day after Jess’s wedding, I hosted the East Coast Hospitality Leadership Summit at the Marston. My hotel, my stage, my favorite kind of chaos. Executives, investors, managers, front-of-house stars with slick shoes and better instincts. I walked the ballroom at dawn and stopped at a raised letter on a plaque on the back wall. The Wellington Collection. My name looked like it belonged to itself at last.

My family came on time for once. My mother wore a navy suit instead of armor. Jess carried Lily on her hip in a green onesie that made her look like a portable spring. My father wore a name badge that read Harold Wellington, guest like everyone else.

After the keynote—half playbook, half confession—I shook hands, accepted too many business cards, promised follow-ups I would actually do. I heard my father’s voice behind me.

“This is my son, Morgan,” he said to a cluster of Blackstone people. “He built this whole thing himself. Proud of him.”

Proud. Of me. Words I’d tuned for in static my whole life and never caught. I froze, not visibly, but in that internal way that registers earthquakes. I didn’t turn around. I didn’t make a scene. I breathed, then kept moving forward because now I knew how.

Jess came over and set Lily in my arms. Lily grabbed my tie with unearned confidence.

“She’s lucky to have you,” Jess said.

I took Lily out onto the harbor terrace when the room thinned. The city glittered. The water reflected without trying too hard. I thought of the kid who stole hotel pens and lined them up on his desk like little soldiers. The kid who wanted to own something big enough that the people who didn’t see him would have to use the front entrance with everyone else. I didn’t feel triumphant. I felt… finished trying to be someone else’s version of done.

In the weeks that followed, my parents were different in small ways that mattered more than apologies. My mother texted photos of the Paris lobby with the kind of wonder she used to reserve for charity galas. My father sent an email asking for advice for a law-school clinic he was mentoring: How do we talk to clients about ethics in a way that doesn’t sound like a lecture? I sent him a page from our training manual titled “Say It Without Making People Defensive.” He wrote back Thanks. I screenshotted it and didn’t tell anyone.

Jess and I made a ritual of coffee every other Sunday. Lily learned to pull my hair and my pride in equal measure. We didn’t talk about the rehearsal night or the text that started it. We talked about sleep schedules and teething and which lullabies aren’t actually for babies if you listen to the lyrics.

On the professional side, the mentorship program multiplied. I made calls people had once made for me. I reviewed pitches at midnight and told the truth in the morning. Tyrell opened his second property. A woman named Dayana who’d been a night auditor in Philly launched a micro-inn near Drexel that became a favorite for visiting professors. She sent me a photo of her sign—The Daylight—lit for the first time at dusk. I bought a frame for my office and put it where my law-school acceptance letter would have gone if I’d had a different life.

We expanded to Paris, then Lisbon, then Montreal. The Marston stayed the hub—the place where I walked into kitchens and managers stopped holding clipboards like shields. We rolled out a concierge app that finally passed the senior guests’ “don’t make me log in” test. We built pathways from housekeeping to management that didn’t require a miracle or a degree. We instituted a policy that no one could be written up without a conversation. The first quarter it cost us time. The third quarter it paid for itself in turnover stats.

Catherine announced her retirement at a staff meeting with cake, and I gave a speech that made even the dishwasher clap in the doorway. “You saw me before anyone else did,” I told her. “You made the map. We just keep tracing it.”

She smirked. “You stopped tracing a while ago, kid.”

When the Paris hotel earned its fifth star, I flew over with my GM and the housekeeping supervisor who’d caught a design flaw before the inspectors did. We stood in a service corridor with ugly lighting and hugged like we were in a cathedral. I texted the photo to Jess. She sent back fireworks and a photo of Lily asleep with a stuffed lobster. I laughed alone in a hallway and didn’t feel lonely.

Six months later, the Marston hosted the city’s biggest charity gala. The planning committee wanted to rehearse with our sommelier; I scheduled the run-through myself and stayed in the back of the room while he talked about mouthfeel with a confidence that made me want to high-five him. My father walked in late; he listened at the door and, when the young man finished, waited his turn to approach.

“Good presentation,” he said. “I was rude once. I’m sorry.”

The sommelier blinked, then nodded. “Thank you,” he said, and later told me he hadn’t needed it but appreciated it anyway. That’s the thing about apologies: sometimes they dissolve something you forgot you had to carry.

In therapy we talked about what it means to offer grace without offering yourself up. We wrote a list titled Boundaries I Keep When I’m Tired and taped it inside my closet. Number one: I do not take business calls after 8 p.m. Number two: I do not outsource my hope to people who didn’t earn it. Number three: I do not apologize for building the thing I needed. I still broke the first rule sometimes. I defended the second one like a religion. The third became a sentence I could say to my reflection and almost believe.

On the anniversary of Paris, I hosted a dinner at the rooftop restaurant. Investors, managers, a few members of the housekeeping team whose schedules I rearranged so they could come in cocktail attire and sit at a table instead of setting one. I invited my parents and Jess without ceremony. They came. My father brought a bottle of something expensive and didn’t tell anyone what it cost. My mother brought a small photo of me at eight in a hotel lobby holding a pen like it was a sword. She slid it across the table to me under a napkin, the way spies exchange microfilm in old movies, and said, “We missed so much. I’m trying not to miss more.” I kept the photo in my wallet for a week before putting it in the box with room keys and the first printed brochure I ever hid under my mattress.

Near midnight, after toasts and speeches and a surprise chorus from three servers who should honestly quit and go Broadway, I stepped into my office and looked at the bank of monitors like a person who’s fallen in love with surveillance even though he knows better. People danced. People made deals. People took photos in front of a wall of flowers that had cost more than my first car. I thought of the text from a year ago that started this version of the story. I opened the security thread and typed:

No restrictions on the Wellingtons. Treat them like family. If they act like it.

Send.

Not because I needed to prove I was bigger than my anger, or better than their worst day. Because I didn’t need revenge to know I’d won. I had my name on the building and my hands on a future that didn’t require permission. I had employees who trusted me, mentors who had my back, mentees who reminded me why I ever cared about check-in flow. I had a niece who tugged my tie and a sister who called me first. I had parents who were learning at a late hour, which is still a kind of miracle.

A week later, my father texted me a photo from the Marston lobby: the sommelier teaching a couple how to hold a glass by the stem. He’s good, my father wrote.

He is, I replied.

You were right, he wrote next.

About what?

Service. It’s not servitude.

I stared at the screen, then typed: Took me a while to learn that too.

When I lock my office at night, I walk the corridor with the framed plaques—the safety award, the five-star rating, the quiet photo of Dayana standing out front of The Daylight with a scissors and a ribbon. At the end of the hall, a window looks over the harbor. The city is a rumor of light. The sign on the building across from us is half-lit; ours glows like it means it. WELLINGTON. I used to want that word to tell my parents something. Now it tells me something else: that some legacies you inherit, and some you have to rename.

Security doesn’t need a special instruction anymore. They know the rule that took me thirty years to write. Treat people like family when they act like it. Treat everyone like a guest you’re proud to serve. And treat yourself like the only permission slip you’ll ever actually need.

The text that started it sits archived in a folder called Keep. Not as a wound. As a landmark. The day my father banned me from a wedding in a hotel he didn’t know I owned, I told security to revoke his VIP access. The day I didn’t need to anymore, I told them to lift it.

Because sometimes the real power move isn’t punishment. It’s peace that doesn’t ask anyone else to cosign. And I have it. In a lobby I designed, under a name I reclaimed, in a life built by hands that learned where every key on the ring fits.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

Boss Fired Me 3 Days Before My Pension Vested After 29 Years With The Company. I Made A Phone Call. CH2

Boss Fired Me 3 Days Before My Pension Vested After 29 Years With The Company. I Made A Phone Call….

My sister’s husband made her sleep outside under a tree with nothing during a storm while she was pregnant. CH2

My sister’s husband made her sleep outside under a tree with nothing during a storm while she was pregnant, i…

At Family Dinner, My Sister Hit Me, Pushed Me Out, and Said “Get Out of My House” — and I Was… CH2

At Family Dinner, My Sister Hit Me, Pushed Me Out, and Said “Get Out of My House” — and I…

My Dad Yelled, “Pay Rent Or Get Out!” At Christmas Dinner, So I Left And Cut Off Every Expense… CH2

My Dad Yelled, “Pay Rent Or Get Out!” At Christmas Dinner, So I Left And Cut Off Every Expense… …

After My Car Crash, I Crawled to the Door My Parents Laughed Stepped Over Me to Leave for Dinner. CH2

After My Car Crash, I Crawled to the Door My Parents Laughed Stepped Over Me to Leave for Dinner …

At The Bank, My Dad Tried To Make Me Sign Everything Away, But Manager Read The Note I Hide. CH2

At The Bank, My Dad Tried To Make Me Sign Everything Away, But Manager Read The Note I Hide …

End of content

No more pages to load