Every Year, My Family Forgot My Birthday—Without Fail. So This Year, I “Forgot” Their Anniversary Surprise. They Shouted, “How Could You Be So Thoughtless?” That’s When I Smiled… And Revealed the Truth.

Part One

Everyone in my family knows the drill: mid-September arrives, calendar squares fill with fittings and florists and linen samples, and the annual flood of emails begins—“We need your draft by the 20th, darling.” “Will you send the place cards to the printer?” “We’re thinking champagne coupes this year, not flutes.” None of these messages mention my birthday.

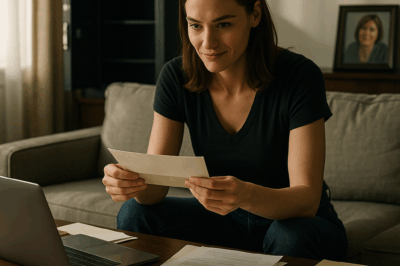

It’s an old comedy we perform like professionals. I wake up, feed the cat, stare at the phone that will not light up, and tell myself, as I’ve told myself for twenty-eight birthdays, that I do not care. Inevitably, a courier arrives with a cream envelope edged in gold filigree: Prudence & Roy—Fifty Years. A milestone glitters on expensive card stock. The joke lands exactly where it always does.

“Mom?” Paisley’s voice startled the cat off the sill. She barreled through the front door with a tote bag, hair twisted into a study-bun that had burst its own pins. “I screwed up.” She dropped keys somewhere by the ficus and wrapped me in one of those fierce, rib-thudding hugs only a grown child can give. “I’m so sorry. I was submerged in finals. I’m a terrible daughter.”

“You’re here now,” I said, smoothing her hair like I still could. “We’ll go to dinner.”

“Before or after you write your annual ode to Grandma Prudence’s indestructible love?” She pulled back and saw the invitation in my hand. Her mouth twisted. “They sent this today?”

“As they have every year.” I slipped the card back into its envelope. “To remind me what matters.”

“What matters,” she muttered, marching to the kitchen, “is that you finally let them stew.” The kettle screeched. “You know I found Grandma’s old birthday calendar last year, right? Every birthday marked in her precise script—except yours.” She handed me tea that tasted like smoke and citrus. “I almost took a Sharpie to it.”

My phone lit like a misbehaving chandelier. Prudence. We watched it ring itself hoarse. Then Marlo with a text as neat as her haircut: “Seven tonight. Mother’s nerves. Please be helpful.” Then Trey with all the grace of a naval broadside: “Don’t be difficult.”

“Don’t be difficult?” I repeated.

“From the man who forgot to invite you to his rehearsal dinner because he ‘assumed’ you wouldn’t want to come.” Paisley snorted. “He also forgot to credit you for line-editing his wedding vows, but sure. You’re the difficult one.”

The phone lit again. Roy this time—my father, who still called his smartphone “the portable.”

“Want to take it?” Paisley asked.

I set the phone face down, the screen a small, gray heartbeat. “Tonight I’m unavailable.”

“Good,” she said. “Let them need you.” She sank onto a barstool, pushing aside the stack of notes that marked where I’d left my manuscript. “How’s the book?”

“The ending finally came this morning.” I touched the stack like it might purr. “It’s simple. The hardest truth to tell is your own.”

“What are you going to tell tonight?”

“That I’m busy.” I raised my mug. “Dinner?”

She cheered quietly, the way she used to after a home run in tee-ball, and texted her boyfriend that we would likely require every carb in the building. We left the phone on the counter and went out. We ate cheese we couldn’t pronounce and bread that crackled, and when the owner sent sparkling wine “for two queens on a quest,” I didn’t cry. Not once.

When we returned, the album waited on my desk like a planted landmine—hand-bound leather with a satin ribbon and my mother’s elegant note tucked under the bow: “For ‘inspiration.’ Bring your sparkle.” I loosened the ribbon.

Fifty years stretched before me: my parents in matching smiles; Trey’s chin lifted like a lighthouse; Marlo always angled toward light; Vanessa perfected into a diplomatic ornament; me—carrying coats, moving chairs, wiping a wine stain with my napkin while my mother toasted “family.” My face was always a peripheral detail, a ghost caught in the gloss of someone else’s glory.

“It’s quite a work of art,” Vanessa said from the doorway, cheeks flushed from haste, fingers clenched around her clutch. “Your mother sent me to talk sense into you.”

“No knocking now?” I closed the album.

“You enjoy theatrics,” she parried. “So do I when I’m invited.” She paced once, heel to rug, rug to hardwood, eyes on everything and nothing. “This anniversary means the world to Prudence. She can’t sleep. She thinks you’re going to do something rash—like publish.”

I opened my laptop. The title page glowed. THE ART OF INVISIBILITY: A Daughter’s Guide to Being Forgotten. Vanessa’s face performed an entire opera in three seconds. “You can’t.”

“Can’t what? Circulate oxygen through a room that’s been sealed for half a century?” I tapped the screen. “It’s not about vengeance, Ness. It’s about oxygen.”

“You’ll humiliate them.”

“They humiliate themselves with ease. They have simply been doing it privately.”

She smoothed a nonexistent wrinkle. “Will you at least come tonight? Give the speech? Then publish if you must.”

I thought of giving a toast with pneumonia while my mother beamed. I thought of the Paris Christmas where they sent me an email with a slideshow from Paris and a note that said, “We thought you had deadlines.” I thought of the time the family photographer told me to take “the candid shots” because my hair “didn’t photograph well.” Then I thought of the way Paisley had looked at me at noon: the squared shoulders, the flint.

“No,” I said. “This year, someone else can talk about love.”

Vanessa pinched the bridge of her nose. “What on earth am I supposed to tell your mother?”

“Tell her,” I said, “that I’m doing exactly as she taught me for twenty-eight years: forgetting what she asked on my birthday.”

The pre-party dinner unfurled the way a careful lie always does—flawless linens, cutlery like a silver army, an air thick with civility and something poisonous underneath.

“More wine, Gabriella?” My mother’s smile could butter a coin. “You look peaky.”

“I’m fine.” I let the server over-fill my glass.

“How’s the writing,” Marlo asked, because she knows the word writing is both opiate and slur in that house.

“Finished,” I said. “Final edits cleared.”

“Marvelous,” my father said. “Proud of you, kiddo.”

“What’s it about?” Trey asked, contempt already fizzing under his teeth.

“Family,” I said, and the room went strangely still, like a string quartet held its breath.

“You will bring copies for the gift table,” my mother said. “A sweet little gesture.”

“A blunt instrument,” I murmured.

“What did you say?” She was still smiling.

“I said I brought something for the table.” I held up the leather-bound album like a holy book. “Proof.”

“Perhaps,” my father suggested, napkin worried between his fingers, “we table this.”

“I have spent thirty years tabling this,” I said. “Tonight I flip the table.”

“Don’t be dramatic,” Trey snapped.

“Don’t be predictable,” I said, and slid my phone onto the linen so they could all see the sender line of my publisher’s email; the subject, Your Galley is Live; the body: We are thrilled. Vanessa inhaled through her nose. Marlo’s phone began to buzz like a hive. My mother stood, then sat, then said as calmly as she could, “Gabriella, you will not destroy the family on our night.”

“Mother,” I said, “if words can destroy the family, perhaps truth should.”

Paisley placed her hands on the table and rose. Her voice cut the room like a bright thing. “Grandma, for years, you have preached tradition which has meant Gabriella labors. If you want tradition, you can keep it and let my mother live.”

“You are a child,” my mother said. “This is complicated.”

“No,” Paisley said. “It’s simple. Love sees. Love remembers. Love does not demand to be the loudest voice in the room.”

My father made a small sound, like grief remembering itself. “I read it,” he said into his plate.

“You what?” my mother whispered.

“Last night. She sent it to me.” He looked at me with an expression I had never been given, not on a stage, not in a kitchen: permission. “She’s right.”

“Roy,” my mother said, voice going thin.

“About the porch,” he said. “Your sixteenth. The blue dress. Waiting till midnight. I saw you. I never forgot. I just … failed to say I was sorry.”

Silence sat down with us and poured itself a glass.

“Thank you.” I meant it.

“This is absurd,” Trey barked, because irony is a lost language for some. “Gabriella, don’t.”

“Don’t what? Exist?” I stood. “I’m leaving. Enjoy the rehearsal for your performance. Consider it a dress rehearsal for the truth.”

“Fine,” my mother said. “We’ll do it without you.”

“You always have,” I said, and walked out.

We ordered a pizza we did not want and ate it in our socks on the floor of my office while the internet flickered and grew. My publisher’s text chimed: GMA yes. Segment at 8:40 live. Can you do tomorrow? Paisley’s: I’ll make your hair behave. Marlo’s: Answer me. Damage control. Trey’s: You are not going to humiliate us live. Vanessa’s: I’m bringing scones. Also I’m sorry. My father’s: Proud of you. I’ll tell your mother in the morning. My mother’s: nothing. That part hurt less than it would have three months ago.

At 8:40 the next morning, I sat under lights that made me sweat through my blouse and told a country that loves tidy arcs that families are messier than redemption essays make them. The anchor asked about forgiveness; I said that forgiveness is a bridge you build from both banks. The chyron read INVISIBLE NO MORE which made me wince and then, to my surprise, smile.

An avalanche began.

Emails from daughters who had never been sung to; sons who grew up replacing light bulbs instead of being told thank you; mothers who realized, suddenly and with horror, that they had let the shiny one blind them to the steady one. Book clubs began to dog-ear and argue. One woman wrote that she walked into her kitchen and told her own daughter she had failed; they both cried; then they baked a cake. I printed that email and taped it above my desk where I could see it when the old ache tried to tell me I had done harm.

“Black car,” Paisley called from the window as evening fell. “Press? Or something worse?”

“Something worse,” I said, smoothing my sweater.

She opened the door to Marlo with mascara slide lines and disheveled hair—my pristine sister in borrowed humanity. “Come fix it,” she said without skipping a breath.

“I’m fresh out of glue,” I said.

“Mother will never survive this.”

“Mother will discover she knows how to survive all sorts of new experiences,” I said, and handed her a wrapped book. “Deliver this.”

“What is it?”

“A mirror.”

She stared down at the package as if she could see her face in it. “You really aren’t coming?”

“Around nine,” I said. “Right when they need dessert and truth.”

She narrowed her eyes. “You are smiling.”

“Yes,” I said. “I am.”

“Why?”

“You’ll see.”

Part Two

My mother’s entry hall smelled like tuberose and control. Cars clogged the circular drive. On the gift table, between a Baccarat vase and a silk-tied box from a Governor’s wife, sat a simple black book wrapped in tissue. The society photographer hovered near the ficus, bored and predatory. The string quartet saw me first; one violinist wobbled on a note and then self-corrected because instincts die last.

“Gabriella,” my mother breathed, clasping my forearms like prayer beads. “Thank God. We will do this properly. You will speak. Then you can have your moment—Tuesday at noon, perhaps.”

I set the tissue-wrapped book in her hands. “Happy anniversary.”

“What is—” She peeled back paper the way she does everything, delicately and with an audience. Gold lettering sailed up into light: THE ART OF INVISIBILITY. A hush fell like snow.

“You wouldn’t,” she whispered, though the tarnished thing in her eyes said she would.

“Release was this morning,” I said. “You have advanced seating.”

“You are not doing this to us.” Her fingers dug crescents into the leather, every knuckle a demand.

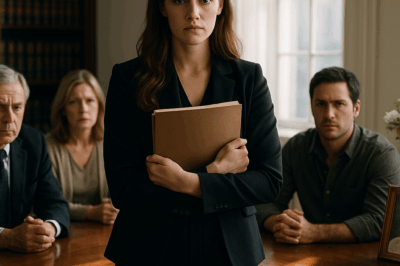

“It is not to you,” I said, and turned to the room. “Hi. Thank you for coming to celebrate Prudence and Roy’s fifty years. It has been my sacred duty to toast them since I was twelve, sometimes while febrile, sometimes from the back of the room when the microphones were busy with better people.

“Tradition is a heavy word,” I continued, pulse calming the way it always does right before a reading. “It can be ritual that keeps us warm. Or a chain we hand our children while we insist it is a charm. For twenty-eight years, my birthday and their anniversary have shared a week. Every single time, my day vanished under this one. So this year, I tried on the tradition you all handed me. I forgot. I ‘forgot’ their surprise. I didn’t book the fireworks my mother requested. I did not confirm the harpist my father wanted, because ‘violins are too common.’ I did not arrange the skywriting over the club that said ‘FOREVER.’”

A tremor went through the crowd, like the first ripple before a lake breaks.

“What?” my mother hissed through her smile. “The fireworks—”

“—were never booked.” I smiled at her in a way that wasn’t. “The pyrotechnics company requires a three-week notice and proof of sobriety on the part of the client. I withheld both.”

“You jeopardized our evening?” Trey barked. “How could you be so thoughtless?”

There it was: the line, the cue, the ancient accusation that had kept me in costume for three decades. I’d known it would arrive. Shame is a well-rehearsed actor; she never forgets her monologue.

I smiled. Heat drained out of my hands. A calm that felt like right posture settled into my bones. “Thoughtless,” I repeated. “Interesting word.” I stepped closer to my mother, held the book where she could see her reflection in the glossy jacket. “For twenty-eight years, my birthday was thoughtless. My graduation, thoughtless. The Paris trip, thoughtless. Your daughter’s existence, thoughtless whenever it inconvenienced the story. This year, I conducted an experiment. I gave you what you have given me.”

My mother swayed imperceptibly. In the corner, the string quartet found their place and stopped pretending to tune. I could feel the room tilt toward me. It was the strangest thing—how oxygen can change the atmosphere.

“Why?” my mother asked, voice shaking not from rage but from something like fear. “Why do this publicly?”

“Because privately didn’t take,” I said. “I have knocked on this door my whole life. You hung hydrangeas over it and told me to admire the bloom.”

Vanessa pressed a cool glass into Marlo’s hand. Marlo held it and didn’t drink. Around us, whispers tried to stand on tiptoe and pretend they were prayer.

My father stepped into the circle, hands lifted slightly, the way you approach skittish animals. “I have an addendum,” he said quietly.

“This is not your moment, Roy,” my mother said without looking at him.

“That’s what I thought when I read her book,” he said. “But I learned something yesterday. There is no such thing as someone else’s moment in a family. There is only what we do with it.” He turned to me. “I told myself for years that silence made me a peacemaker. Turns out it made me a co-author.”

He turned toward the room. “On her sixteenth, I watched Gabriella sit outside until midnight in a blue dress she saved two months for. I watched—and I decided not to make trouble.” His voice snagged. “My daughter’s grief became a small cost to keep the machine running. I knew better. I did it anyway.”

The room exhaled. My mother stared at him like betrayal had come home in his shirt.

“I won’t belabor,” he said, “but I want to say this to every person here who benefits from the loudness of people like my wife. Do not confuse competence with invulnerability. Do not call your most reliable love ‘the strong one’ and then use that label as a drawer where you store your negligence. My daughter has paid the family tax for thirty years. Collection is over.”

The society photographer, to her credit, put down her camera.

Near the back, the governor’s wife shifted her clutch from one arm to the other and whispered into the Governor’s ear. He gave a small, stunned nod and squeezed her hand.

My mother recovered her poise like a person reaching for lipstick while the house burns. “A charming performance,” she said, “but we have actual guests and actual vows. We will not indulge this—this—”

“Truth,” Paisley supplied.

“—this public tantrum.”

“Taught by master tantrum-throwers,” I said gently. “I learned from the best.”

She held out the book. “Take your … pamphlet and leave.”

“No,” I said. “You keep it.” I turned to the room. “If anyone would like a copy after cake, we have pre-signed galleys by the exit next to the coat check. The proceeds are going to a fund that will deliver birthday cakes to children whose families are not good with dates.”

A laugh rippled—small and slightly guilty. My mother’s mouth thinned. “You have humiliated me.”

“No,” I said. “I have finally humiliated the story that humiliated me. There is a difference.”

Trey found his courage behind the piano. “Gabriella, you will not—”

“Brother,” I said in my best imitation of my mother’s silk, “there is not a syllable I can add to your education that would alter your behavior in the next fourteen minutes.” He flushed, sank back. Vanessa took his arm. She is too smart to let him speak into a microphone.

Marlo looked at me over her glass and, very slightly, dipped her head. I dipped mine back. We had not made peace. We had made room.

“I’m leaving now,” I said. “You can choose to cut the cake to a waltz and pretend the frosting is not bitter, or you can pick up a fork and eat a slice of reality. It goes down easier with caffeine.”

On my way out, my mother put a hand on my wrist. It was the lightest touch she had given me in thirty years. “I notice you,” she said, voice barely audible, and for one lean second, I saw the girl she had been, the one who became my mother like a surprise you don’t get to unwrap. Then the moment passed. She released me. We gave each other back to air.

The morning after that strange, beautiful implosion, I made tea and opened my inbox to letters that felt like a thousand small lanterns floating down a river toward me. I wrote back where I could. I sent links to therapists; to cake recipes; to maps that showed where to buy cheap candles. People sent me photos of women in kitchens blowing out candles with their daughters, cake crumbs and mascara. We built a little church.

At 10 a.m., my mother arrived fifteen minutes early with scones, eyes swollen, a leather calendar under her arm like a relic. “I did a thing,” she said as she crossed into my office. “I want to show you if you’ll let me.”

She sat primly on my sofa, opened the book, and revealed months rewritten in ink—dotted hearts by my birth date for every year since 1975; my debut novel circled with gold; GABRIELLA’S DAY scrawled with audacity over Anniversary Week in September.

“I cannot undo,” she said, tone oddly simple. “I can do different things.” She smiled tightly. “Did you know I have dozens of your drawings? You made a horse that looked like a dog and a dog that looked like a horse and I kept both because I knew you were going to make something out of stubbornness.”

I should have rolled my eyes. I accepted the gift like a combustible and set it carefully on the table.

Father arrived fifteen minutes later with a small box. “I meant to give you this on your sixteenth.” A bracelet glinted in tissue—thin, silver, delicate. He told me the story of how he had hidden it in his dresser to keep it from my mother’s curation and then hidden it from himself. Regret steals the most expensive things.

“Thank you,” I said, fastening it with fingers that shook.

By noon, Marlo had sent an interview to be placed in Tatler about “the virtue of letting truth re-arrange a table.” Trey texted a photo of an apology cake he had ordered from a bakery with “I’m sorry, G” scripted badly in frosting. Vanessa sent me a calendar invite: Tea Wednesday 3 p.m. with a note that said, I will keep the conversation civil and the scones warm.

Paisley taped a sticky note above my desk that read, THIS PLACE—Wednesdays, 3 p.m.—Attendance: Optional, Honesty: Mandatory, and we laughed, giddy with the glory and terror of starting a tradition we are not qualified to run.

At three precisely, my mother returned with lemon drizzle. She sat on my sofa like a woman on a bench below an executioner and sipped her tea. She turned the bracelet on my wrist with a finger like a question. She pulled out the calendar again as if to insist that ink could make a future behave. We had nothing like closure. We had, finally, a beginning.

That evening, I introduced a new ritual. On the day of my birth, every year, I would send one cake to one stranger who needed to be visible. I wrote checks to small groups that do this without books. I wrote a letter to the governor’s wife thanking her for telling me we had made her call her sister and apologize for three decades of tiny cuts. I wrote to the photographer and asked for the proofs from the moment my mother held the book. She sent them with a note: “I didn’t lift my camera during your father’s speech. Some things are not mine to take.”

And to the people who asked me online, in interviews, at readings, how it felt to stand in a ballroom and tell your mother you would not be her mirror anymore, I said this:

“It felt like oxygen. It felt like confirming a rumor to yourself.”

It also felt like grief. After the tour, after London with Marlo and croissants with too much butter and a panel with women who had stopped calling their daughters “the strong one” and started calling them by their names, I went home and cried for the girl who waited on the porch in a blue dress. I wrote her a letter and tucked it into the album under the Paris photo. I told her I see her now. I told her she was always loud. The room was simply too privileged to hear her.

Two months later, Paisley graduated law school and took the bar. In her valedictory, she quoted a line from my epilogue—“Sometimes the only way to be heard is to stop speaking altogether.” She paused, looked at me in the crowd, and said, “Or to speak so plainly that the world has to re-tune.”

On the anniversary of their anniversary, I sent my parents a card. It was not edged in gold. It did not announce a gala. Inside, I had written, “Fifty-one. Still married. Still trying. That’s what matters. See you Wednesday for tea.” My mother called and we spoke for three minutes without anyone crying. She told me she had baked the scones with too much lemon because grief makes you heavy-handed with zest. I told her lemon is better overdone than underdone. We laughed like people who will one day like each other and sipped.

Sometimes guests at the club still lower their voices when I walk past. Sometimes an aunt I have not seen since 2009 sends me an essay insisting I have become cruel. I file those letters in a folder labeled Gloss and, on bad days, I pull them out and marvel at how fear looks on fine stationery.

Mostly, though, the world quieted. The maple outside my office throws the kind of shadow writers beg the heavens for. The cat snores like gratitude. Every Wednesday at three, whoever can sits in my living room with tea and scones. We talk about the week’s series of becoming visible. We watch the sky move. We sometimes speak about the years the sky did not move at all.

And when September comes, and the cream envelopes avalanche and the florists call and the women at the rental company ask if we want coupes or flutes because coupes “photograph like dreams,” I smile and say, “We’ll pass. We have cake.”

Because in the end, after the interviews and the cold shoulders that warmed and the calendar rewritten and the bracelets finally clasped, the miracle was not that I stood in a room where no one was allowed to be visible and lit a match. The miracle was that after the room filled with smoke, people opened windows.

I had not forgotten their anniversary. I had remembered what it meant to love myself more than tradition. And I had finally, finally taught the people who taught me how to forget that the opposite of “thoughtless” is not “obedient.”

It is “seen.”

END!

News

I Trusted My Mom with $8M. Next Morning She Vanished with It—I Laughed Because of What Was Inside. ch2

I Trusted My Mom with $8M. Next Morning She Vanished with It—I Laughed Because of What Was Inside Part…

I Walked Into My Son’s Hospital Room to Say Goodbye—Then I Heard the Nurse Whisper the Words… ch2

I Walked Into My Son’s Hospital Room to Say Goodbye—Then I Heard the Nurse Whisper the Words… Part One…

For My Son, I Accepted My Boss’s Strange Marriage Proposal — But What I Didn’t Expect Was… ch2

For My Son, I Accepted My Boss’s Strange Marriage Proposal — But What I Didn’t Expect Was… Part One…

At The Courthouse Wedding, I Left My Fiancé And Escaped With A Stranger — Because I Realized… ch2

At The Courthouse Wedding, I Left My Fiancé And Escaped With A Stranger — Because I Realized… Part One…

They Lied Grandma Was Dying for One Reason—So I Took Everything Back. ch2

They Lied Grandma Was Dying for One Reason—So I Took Everything Back Part One The morning sunlight poured through…

At the Family Dinner, My Husband Humiliated Me—and Everyone Laughed… But Then He Froze at the Door. ch2

At the Family Dinner, My Husband Humiliated Me—and Everyone Laughed… But Then He Froze at the Door Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load