During Sister’s Residency Match, She Laughed At My Diagnosis—Her Program Director Didn’t

Part I

The invitation arrived on thick ivory card stock that looked expensive enough to bruise. Embossed letters arched with celebration: You’re invited to celebrate Dr. Amanda Chen’s residency match at Johns Hopkins Department of Surgery. Gold confetti drifted along the borders like it had already decided joy was inevitable. The postmark on the envelope said three weeks before my surgery. The date inside—March 15—sat one day after mine.

Mom called as if she couldn’t hear the arithmetic. “You’re coming, right? Amanda specifically asked if you’d be there.”

“My surgery is the day before,” I said, and even saying it out loud made something low in my spine tighten, as if the tumor had ears.

“Oh,” she said, the syllable landing like lint. “Can’t you reschedule? This is Amanda’s moment. She’s worked so hard.”

My moment had been scheduled by a tumor that did not care about cake. NF2—neurofibromatosis type 2—doesn’t care about much. Three letters and one number that meant hearing loss from bilateral vestibular schwannomas, a constellation of meningiomas, and now a mass coiled around my thoracic spinal cord like a sleeping serpent with a grudge. If I waited, the neurosurgeon said, I would lose my legs by summer. If I didn’t wait, I would miss the party.

“I can’t reschedule,” I told her. “Dr. Richardson says we can’t wait.”

“We’ll try to make it to the party if you can,” Mom replied briskly, as if she were discussing weather. “Amanda’s colleagues will be there. It would mean a lot.”

After she hung up, the invitation still lay in my lap, heavy as a verdict. Amanda, two years older, had always been the family’s favorite paragraph—awards, perfect GPA, acceptance letters lined up like suitors. I was the parenthetical, the aside you could skip without losing the plot. When NF2 hit at twenty-three, I became a footnote no one knew how to cite. It complicated the story: Amanda the doctor, Claire the inconvenient patient.

A text pinged from Amanda: Mom says you might miss my party because of another surgery. Really? Can’t you postpone one day?

I stared at the screen until the letters blurred. I didn’t reply. It is difficult to explain spinal cord decompression to someone who treats it like a hair appointment.

Dr. Patricia Richardson did not treat anything like a hair appointment. Head of neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins, she carried a calm that looked like it had been ironed. In her office, she pulled up my MRI and spoke to me like I was a person who could handle truth.

“It’s wrapped around the nerve roots,” she said, tapping the bright snake on the scan. “We’ll make an incision from T5 to T7, decompress, and try to peel it off the roots without injuring the cord. I’ve done this procedure hundreds of times. You’re young. Your prognosis is excellent.”

Her eyes flicked up. “Is your family here?”

“They’re… preparing for my sister’s party.”

“Amanda Chen?” Her tone was neutral but alert.

“You know her?”

“I’m her program director,” she said. “She didn’t mention you were having surgery this week.”

I wanted to make a joke, a poor one. I wanted to say, She’s busy. I wanted to say, It’s always been like this. Instead, I nodded, and Dr. Richardson did what good surgeons do when words are fractures: she put a steady hand on the edge of the table and gave me a plan I could hold.

Match Day came with balloons and screaming crowds across the country, med students ripping open envelopes that altered the map of their lives. My day began under hospital fluorescents at 5:15 a.m., the pre-op bay divided by curtains that didn’t keep anything private. My parents dropped me at six, my mother’s “Good luck” already halfway out the door, my father maneuvering a garment bag for a blazer he’d wear later in photos. Amanda didn’t call.

In a blue gown that never closes properly and a paper cap that made me look like the disposable version of myself, I signed forms acknowledging I might not walk again. A nurse wrapped a blood pressure cuff around my arm and made small talk about the weather. The anesthesiologist—eyes smiling above his mask—asked about allergies. And then Dr. Richardson came, scrubs green, hair tucked, voice steady.

“Claire,” she said. “Ready?”

“Define ready.”

“That’s fair.” She pulled a stool close, showed me the images again as if repetition could untie this knot. “We’ll keep you intubated for a bit in recovery to control pain. I’ll see you on the other side.”

“Do you sleep on nights before surgeries like this?” I asked, surprising myself.

“I’ve learned to,” she said. “It’s part of the job—resting when you can, choosing focus when you must.”

The doors swung, the hallway narrowed to a strip of ceiling tile, and the lights marched overhead like a quiet army. I thought of the invitation still on my counter, of gold confetti that didn’t care either way.

Part II

There are six hours missing from my life that day. The story of what happened belongs to other hands, other eyes, a clock mounted too high on an OR wall. When I came back to myself, the first thing I knew was pain. Not sharp. Vast. As if someone had opened a door and winter rushed in. The second thing I knew was Dr. Richardson’s voice calling my name across a distance.

“Claire? Wiggle your toes.”

My left foot moved, then my right, like shy animals peering from brush. I cried—a small, animal sound I would have been embarrassed by on any other day.

“All of it’s out,” she said. “You did beautifully.”

Beautifully is not a word you expect after someone has split your back. I clung to it like a charm.

They kept me in recovery longer than the clock deserved. I floated up through the anesthesia’s milk and then slid back down. Sometime in the late afternoon, a nurse named Lila with deep laugh lines and a voice you’d trust with secrets adjusted my PCA pump and tucked the blanket around my shoulders with a tenderness that nearly undid me. “Your surgeon is a legend,” she said. “You’re lucky.”

Lucky: an odd word when you are counting incisions.

Night brought the soft roar of a hospital never sleeping—carts humming, heels counting, the sigh of doors deciding whether to open. At nine, my phone buzzed on the tray table. Amanda’s face filled the screen, gleaming under chandeliers. “Claire!” she said, voice bright with champagne. “Look!”

The camera swerved—sequined dresses, tuxedoed men, a banner with her name and Johns Hopkins in an elegant serif, candles lifting themselves toward ceilings our childhood home had never known. She turned the camera back to herself. “Can you believe it? Even some attendings came!”

“That’s great,” I managed, the breathing tube’s ghost still lining my throat. “I had my—”

“How was your thing today?” she asked, eyes already searching the crowd for someone else to impress.

“My thing?” I repeated.

“You know—your procedure.”

“It was a six-hour spinal cord tumor resection, Amanda.”

“Right,” she said, too brightly. “But you’re fine. You always bounce back. Take your meds.” She glanced over her shoulder. “Oh, wait—Emily’s here. She matched Hopkins too. I have to introduce her—”

The camera bounced as she moved through the crowd, my face a postage stamp riding in a corner. Her voice, lifted for someone nearby: “That’s my sister Claire. She’s always having some medical thing. Honestly, I think she likes the attention. Basic stuff, really. Just some back procedure. Nothing serious.”

The pain in my back was a distant planet compared to the one that rose then. It had a different gravity, heavier than bone, older than blood. I closed my eyes. The room did not change. My chest hurt.

Another voice cut through—cold, precise, unmistakable. “Basic stuff.”

The camera steadied. Amanda’s face drained. Behind her stood Dr. Richardson, hair still under a disposable cap, a sterile gown thrown on over scrubs, like she had come from another battlefield.

“Dr. Richardson,” Amanda said too quickly. “I didn’t know you were coming.”

“I was invited by your parents,” Dr. Richardson replied, voice low enough to be a scalpel. “I wanted to congratulate you personally. And then I heard you describe your sister’s spinal cord tumor resection as ‘basic stuff’ and ‘just some back procedure.’”

The party’s sound dimmed as if the room itself wanted to listen.

“I didn’t mean—”

“You’re still on FaceTime,” Dr. Richardson said, cutting through apology like tissue. “With your sister. The woman I operated on for six hours today. The woman with NF2, a complex genetic disorder. The woman who will require lifelong surgical management. Not a prop for you to diminish when it suits the narrative.”

She looked directly into the camera. “Claire, I’m sorry you heard that. I’m coming to check on you now. Amanda, I’d like to speak with you privately.”

The screen went black.

Thirty minutes later, Dr. Richardson stood by my bed, hospital light making her look carved from steadiness. “How’s your pain now?”

“Seven,” I said. I had learned how to grade my own suffering, a skill I hadn’t wanted.

She adjusted the pump and sat. “I need to tell you something,” she said. “And I need you to know: none of this is your fault.”

The last time someone had said those words to me was when a pediatric neurologist put a name on my teenage headaches and sent us home with pamphlets and silence. They landed now and made a space around my heart.

“What happened?” I asked.

“After we disconnected, I asked Amanda to step outside with me. I wanted to understand why she’d minimized your condition to her colleagues.” Dr. Richardson’s jaw moved once, a muscle working. “She said you’re dramatic about health ‘stuff,’ that you exaggerate for attention, that your surgeries aren’t serious because you look fine between them.”

The heat that rushed my face embarrassed me and had nothing to do with fever. “She’s always been like that,” I said, hating the smallness of my voice.

“That doesn’t make it acceptable. Especially not for a surgeon.” Dr. Richardson’s eyes held mine. “I have your medical file. You have bilateral vestibular schwannomas. You’ve had three spinal surgeries. Multiple meningiomas under surveillance. None of that is basic. Minimizing complex illness kills people, Claire.”

I nodded, and the nod felt like a confession I didn’t owe.

“I’m meeting with the residency leadership tomorrow,” she said. “To discuss Amanda’s fitness for our program.”

“What does that mean?” The question came out more as breath than sound.

“It means we will decide whether someone who demonstrates such profound lack of empathy and clinical judgment should be training as a surgeon at Hopkins.”

Between the pain and the morphine and the exhaustion, my mind tried to sprint and stumbled. “They’ll say it’s a family thing,” I muttered.

“This is not a family thing,” she said. “This is patient safety.”

Part III

Amanda called me seventeen times the next morning. I answered on the eighteenth out of a reflex that came from before tumors, before white rooms, before invitations lined with gold.

“Claire, please. You have to help me. Dr. Richardson is threatening to withdraw my match. She says I’m unfit. This is insane.”

“You called my spinal cord tumor ‘basic stuff’ while I was in recovery,” I said.

“I didn’t mean it like that. I was trying to make people comfortable. You know how awkward it is when—”

“When someone makes your sister’s body the punchline?”

“That’s not fair.”

“It’s not fair that I have NF2,” I said, surprising myself with the flatness of my voice. “It’s not fair that I learned to lip-read because tumors ate my hearing. It’s not fair that I measure my life in MRIs. But here we are.”

She took a breath, then another, the sound of someone trying to win a race they chose. “Okay. Sometimes I thought you were dramatic. But I didn’t mean it. I don’t deserve to lose my residency over a comment at a party.”

“This isn’t about a comment,” I said, a calm entering me like a tide. “It’s about years of making my pain smaller so you could keep being big. Your colleagues told Dr. Richardson you joked I probably Googled my illness. You told people I’m a hypochondriac.”

Silence. We have different kinds of silences, ours. This one had weight. It pressed.

“Call Dr. Richardson,” she said finally, voice breaking. “Tell her it was a misunderstanding.”

“It wasn’t,” I said. “You meant it.”

“So you’re just going to let them destroy my career?”

“I am not doing anything,” I said. “You did this. You showed them who you are in a room full of people you wanted to impress. They believed you.”

She hung up, then called again. I let it ring until the phone learned something about boundaries it had missed.

Three days later, I left the hospital with a back that felt like a closed door and a bag of medications that rattled like small storms. My hair was greasy under the cap. My legs moved like they remembered me. Dr. Richardson came in civilian clothes that looked wrong on a warrior. “You’re walking beautifully,” she said, and I stored the word beautiful in the drawer where I keep strength.

“We met this morning,” she added.

“And?” I asked, as if there were another answer.

“We’re withdrawing Amanda’s match.” She spoke gently, without triumph. “We cannot train a surgeon who mocks illness and minimizes pain. Not here.”

I closed my eyes. The relief I felt made me ashamed for a moment. It passed, and what remained was something like rightness.

“That’s her dream,” I said, because I am the kind of person who still worries about the wishes of people who don’t worry about mine.

“And this is the consequence of her choices,” Dr. Richardson replied. “She can reapply next year. She’ll have to explain. She’ll have to do the work. But no one will die because she didn’t feel like seeing them.”

My phone buzzed on the bedside table with a text from my mother: How could you do this to your sister. You’ve destroyed her future. The words burned my eyes without heat.

I turned the phone off.

The next weeks were a study in small distances: bed to bathroom, couch to kitchen, chair to window. Pain is not only a sensation; it’s a geography. Friends came with soups and silence. A girl from an online NF2 group sent me a playlist of songs without lyrics for days when words were exhausting. I found a therapist who specialized in chronic illness and didn’t treat me like a riddle. We built a plan that had nothing to do with other people’s confetti.

My father did not call. He sent an email with subject line: Disappointed. The body read, You’ve embarrassed this family. He CC’d Amanda and Mom like a bad joke. I closed my laptop and stood by the sink until the faucet stopped looking like a choice.

At my six-week follow-up, the MRI was clean. “We got it all,” Dr. Richardson said. “Incision looks good. Strength’s coming back.” She took off her glasses and studied my face as if I were a scan worth reading. “How’s your support?”

“Changing,” I said. “Better than I thought it could be, worse than I wish.”

She nodded. “Sometimes we need to build a new family around the old one.”

“How’s Amanda?” I asked, surprising myself.

“She’s in therapy, I’m told,” Dr. Richardson said carefully. “Applying to smaller programs. I hope she learns what this means. For her sake and her future patients.”

I imagined Amanda in a too-bright room, shredding a tissue, learning the word empathy after years of using it as punctuation. I hoped so too. And then I let the image go because my hope is not her fuel anymore.

Part IV

Grief did not vanish when the stitches dissolved. It changed shape. There is the grief for what tumors took—a piece of hearing, a summer, hours and hours and hours—and then there is the grief for the family you thought you had. The second one is trickier; it sneaks. It hides in songs and grocery aisles and weekend mornings that used to belong to other people.

I learned new rituals. Every Sunday I FaceTimed a woman named Erin from the NF2 group who lived three states away and wore a cheerful scarf over her port like an act of defiance. On Mondays I wrote exactly one email to a person who had shown up during the surgery and told them one thing I appreciated; it didn’t have to be big. On Wednesdays I took walks that were really measured strolls, counting benches like blessings. On Thursdays I volunteered two hours at the family resource center on the oncology floor—laminating schedule cards, pointing confused relatives toward elevators, making coffee so weak no one could object.

At the center I met a boy with a scar shaped like a question mark along his neck. He pointed at mine one afternoon while his mother argued with pharmacy billing. “Does it hurt?” he whispered, as if pain were a secret best respected.

“Less every day,” I said.

He touched his own scar. “Mine too.”

We sat in a righteous silence that felt like love.

One afternoon, Dr. Richardson found me there while dropping off flyers for a grand rounds lecture on bias in clinical decision-making. “Come talk,” she said later, standing in my doorway with a paper cup. “Five minutes. Tell them what it feels like when someone calls your illness basic.”

“I don’t do stages,” I said.

“You do truth,” she said. “That’s the point.”

So I stood at a podium in a room filled with white coats and told a story I had sworn to stop telling. I kept it small: the invitation, the party, the words, the phone, the click. I did not cry. You do not have to break to make a point. When I finished, a resident in the second row held his gaze at his shoes for a long time and then raised a hand. “My sister has lupus,” he said. “I’ve been… impatient.” He didn’t finish. He didn’t have to. We all heard the rest.

Afterward, Dr. Richardson stood beside me as people shuffled out and said the phrase that had become a lighthouse for me: “Not in my program.” It did more than punish. It protected.

Amanda sent one email in June. The subject line was my name. The body said, I’m sorry. I didn’t know how to be anything but the version of myself everyone expected. That’s not an excuse. I’ve started over. If you ever want to talk, I’ll be at this number. She didn’t attach conditions or urgency. I didn’t reply right away. I read it again a week later and let it sit on my chest like a warm stone. Sometimes repair starts with silence that isn’t avoidance; it’s breath.

Mom texted twice over the summer. Once a photo of lilies in our backyard, the flowers bright as if they were trying too hard. Once to ask about my incision, her language careful, like she was learning to speak to me without weapons. Dad sent an article about perseverance with no comment and I laughed, actually laughed, because maybe even stone rattles when you tap it enough.

On the anniversary of the surgery, I bought myself a cake. Not a small one. I wrote my name on it in clumsy blue icing at the bakery counter and the teenager behind the display case didn’t bat an eye. I took it to the balcony and ate a slice as the city turned itself gold and then went dark. I toasted with ginger ale because I am a cliché in some ways and proud in others.

To people like us, I whispered. To the ones who wiggle their toes when asked. To surgeons who carry their empathy into parties as well as ORs. To program directors who make policies with spines. To sisters who might learn.

My phone buzzed. A message from Erin: How’s your beautiful back doing today? I sent her a photo of the cake. She sent back a GIF of a fireworks display that looked like hope pretending to be loud so grief would hear it.

Later, when I climbed into bed and turned onto my side carefully, I thought of that night—the phone in Amanda’s hand, my face a neglected square on a screen, and Dr. Richardson’s voice entering the frame like a boundary made of steel. I had spent years being laughed off, being shrugged into silence. A woman who had taken a tumor from my spine refused to let my story be minimized. It rearranged something fundamental in me.

My sister laughed at my diagnosis because it took up space she wanted. Her program director didn’t laugh. She took the match back with the same steady hands she uses to return function to bodies. The cut hurt. It also saved something.

I do not know who Amanda will be in a year or five. I hope she learns to hear. I hope I do too, in a different way. The thing I know is this: my pain does not have to be palatable to be real, my surgeries do not need applause to count, and my life is not an inconvenience in somebody else’s story. It is mine.

Outside, a siren wailed and then passed. Inside, the ache in my back faded to a dull presence, not a sentence. Sleep came like a gift that no longer had to be negotiated. In the quiet before it took me, I said the line I had been waiting to deserve:

Not basic. Not ever again.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

HOA Demolished My Lake Mansion for “Failing to Pay HOA Fees” — Too Bad I Own The Entire Neighborhood

HOA Demolished My Lake Mansion for “Failing to Pay HOA Fees” — Too Bad I Own The Entire Neighborhood …

They Mocked Her at the Gun Store — Then the Commander Burst In and Saluted Her

They Mocked Her at the Gun Store — Then the Commander Burst In and Saluted Her Part I —…

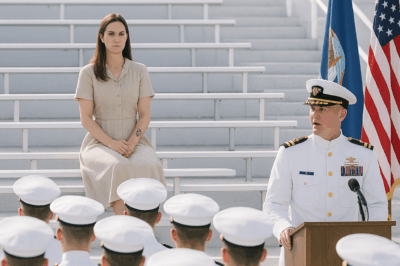

She Only Came to Watch Her Son Graduate Until Navy SEAL Commander Saw Her Tattoo and Froze

She Only Came to Watch Her Son Graduate Until Navy SEAL Commander Saw Her Tattoo and Froze Part 1…

“What’s that patch even for ” then the colonel said,“Only five officers have earned that in 20 years

“What’s that patch even for” then the colonel said, “Only five officers have earned that in 20 years” Part…

My Sister Mocked Me At Dinner “Photocopier Captain?” — Then Dad’s Old War Buddy Saluted Me

My Sister Mocked Me At Dinner “Photocopier Captain?” — Then Dad’s Old War Buddy Saluted Me. At dinner, my sister…

Family Demanded To ‘Speak To The Owner’ About My Presence – That Was Their Biggest Mistake

Family Demanded To ‘Speak To The Owner’ About My Presence — That Was Their Biggest Mistake Part I —…

End of content

No more pages to load