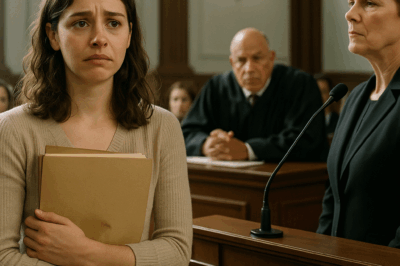

“Do It, Daniel. End Her” My Sister-In-Law Said As My Brother Beat Me Bloody

Part 1

I never imagined that the blood bubbling at the corner of my mouth would be there because of my brother’s fists. The tiles were the same ones we’d skidded across as children when the house was new and the rules were only about not scuffing the polish. I could see my face reflected in their sheen between droplets—split lip, swelling cheek, a smear of red that didn’t look like it belonged to the girl who had once run these hallways with plaits flying and knees perpetually bruised from climbing mango trees in the back garden.

“Sign the papers, Adora,” Daniel bellowed. “Or I swear I’ll break every bone in your body.”

The deed lay between us, torn and crumpled, our father’s name in careful script bisected by a rip that felt like a tear at the world’s edge. He had used the heavy black pen he reserved for documents that mattered—leases, contracts, the first loan he signed when he borrowed against a boat to buy a truck to carry someone else’s goods. Names have weight when you write them with a pen like that; I learned that from his hand resting on mine as he taught me to form each letter.

“Do it, Daniel. End her,” Lydia hissed from the doorway, her perfume too sweet for the heat, a venomous flower. “She’s nothing but a stubborn fool.”

I propped myself on an elbow and wiped blood from my mouth with the back of my hand, tasting iron and memory. Daniel loomed above me, veins raised in his neck, knuckles scabbed from other fights won by other kinds of men. There had been a time when his shadow over me meant safety, when he was the boy who put himself between me and boys in the market who thought the word “girl” meant “prey.” There had been a time I would have given him the house just to see that shadow be a shelter again.

“Look at me,” he snarled, because for a certain kind of rage to do its work, it must be witnessed.

And then, from behind them, a voice: “Stop.”

Not loud. Deep. Steady. The kind of word that changes the air.

Chike.

To understand why my brother would rather see me hurt than see me inherit what was mine, you’d have to know the kind of family I came from. Ours was a house built twice over: once in brick and mortar and once in the stories told around tables. Our father, Chief Okeoma, had become a story while he lived. The boy who sold smoked fish with his mother at the river’s edge while learning to negotiate freight by eavesdropping on the men. The teenager who drove a borrowed lorry on a prayer through storms to deliver textiles on time because a delay would have bankrupted a man whose wife had just given birth to twins. The man who would one day sign papers in an office under a ceiling fan and see his name on letterhead for the first time and take the paper home to show us because he wanted us to know what it meant to write yourself into the world.

He was a contradiction that fit our country: stern and laughing, feared and adored, generous and exacting. He believed in work like holy men believe in ritual. He believed in home like sailors believe in stars. He named the house after my mother, Nkem, because he said the moment he could fix a place to a woman, he knew he had fixed his life to something worth tending.

Daniel was his first son, and people said the two of them were mirror and image. As a boy, Daniel learned to greet men with a hand that felt like promise and to talk numbers like he had been born with an abacus in his pocket. He could recite the price of diesel to the naira and the name of every driver who would never steal gasoline from the tanks. He could charm a customs officer without handing over a bribe. But hunger is a shadow that sometimes looks like ambition until it inches up your back.

The second-born, Chike, was the quiet river that looks shallow until you put your foot in and feel the pull. He could take an engine apart and put it back together while listening to anyone talk without needing to fill the silence. He asked questions in few words, but they were the right questions.

And I was the last: Adora, father’s jewel. I hate the way that sounds on paper; it makes me a trinket. But he meant it and he made me know where my shine came from—work and wit and a stubbornness like his. “You will learn to read the river and the books,” he said when I tried to follow the boys to the yard one summer. “You will know why we carry and why we keep. You will know the worth of a house.”

People saw our wealth and thought we had everything. But cracks run beneath marble sometimes. There was the day Father came back from Benin City with gifts: a toy car for Daniel with doors that opened and closed, a book of maps for Chike, a little bracelet for me with four real gold beads because he said every girl should have the weight of the world on her wrist so she would not forget to lift it. Daniel lost his temper when he learned the beads were not brass. He threw the toy at the wall and shouted until Mother sent the boys to the courtyard. From the corridor I heard Father say quietly, “Greed will destroy you, Daniel, if you do not learn to master it.”

He never mastered it.

Years later, when Father’s cough began as weather and settled into climate, he called us to the sitting room on a Sunday when rain made conversation a small thing. The windows fogged with steam from the kitchen where Mother’s pepper soup had made itself known. Father eased himself into his chair—his back had started to betray him—and placed his hand on the armrest like a man steering a boat.

“This house,” he said, and we all looked because the house was not only walls and porch and orange trees in the back, it was every decision that had stacked up to become rooms. “This house is not property. It is allegiance. It will not go to the one who sees it as an asset. It will go to the one who sees it as home.”

Daniel smiled the way men smile when a preacher is on their side. Fathers pass houses to first sons. That is the story the first sons like best. But Father’s eyes rested on me for a heartbeat too long and a voice like cold water went through me.

When he died, the lawyer came with his briefcase and his formal shoes and his voice that learned to say grief words without cracking. He spoke names and numbers and deeds and bank accounts. Daniel would have the businesses—the trucks and the warehouses and the contracts; it made sense. Chike would have the trusts to manage for the community projects Father had taken on quietly—school roofs, a clinic generator, a library. And the house—Mother’s house, Father’s house, our house—was mine. Solely. Irrevocably.

I watched the color shift in Daniel’s face like harmattan light. Lydia hissed before he did. “A woman cannot inherit the family home,” she said, and then smiled as if she were helping by putting the words into the room so we could all stare at them and realize how foolish they were.

“The Chief was clear,” the lawyer said, adjusting his glasses. “The house belongs to his daughter. No lien, no mortgage, no co-signature. He said she would know why.”

I knew why. Father had read the river and the books. He knew which of his children could leash an appetite. He knew which would put the house behind a locked gate and leave the lights off. He knew which would plant jasmine at the base of the stairs and ask where the breeze would be on a Friday evening in July.

For a while Daniel pretended. He brought wine that cost more than the tiles under our feet. He said “family” like a bargain. “You don’t really need this house, Adora,” he said on the verandah one night, the streetlights turning his face into someone I couldn’t place. “Think of your future. I can buy you a mansion in Oniru. I can give you a flat in London. But this—this belongs to the firstborn by tradition. This is how we honor Father.”

“It’s not about mansions,” I said. “It’s about what he wanted. It’s about what he trusted me to hold.”

Kindness dried from his eyes like water on hot stone. From then on our conversations were pinned insects in display cases: dead things arranged beautifully for guests. Lydia found her moment two weeks after the reading of the will. She came to me with hands that had never peeled a yam and a face that had learned to pout as a weapon. Her perfume arrived before she did and stayed after. She leaned so close I could count the mascara clumps on her eyelashes.

“You are young,” she said. “You are unmarried. You are childless. You don’t deserve this house.”

“Deserve is a word for men who need to be forgiven before they ask,” I said, and walked away because you can only talk to perfume for so long before you begin to feel intoxicated.

The attack came like rain in a dry season—shock followed by inevitability. The shatter of glass threw me out of sleep. Rough hands yanked me from sheets that still held Father’s smell if I pressed my nose to the pillows. Daniel’s men pinned my shoulders. Daniel’s face was rage and story—a boy who had been told a tale where he ends up in the big house and could not bear the version where he stands outside the gate.

“You have embarrassed me for the last time,” he said, the words like oil fire—hot and slick and dirty.

I fought. It was not noble. It was animal. I grabbed and bit and clawed because there are moments when you meet your age and there are moments when you meet your species. His fists were geography. Pain came in waves. Blood makes the mouth taste like pennies and shame. Past his shoulder I saw Lydia framed in Lamplight like a painting of a queen in an empire that had fallen. “Do it, Daniel,” she hissed. “Break her. End her.”

“You will never have this house,” I managed, and it was foolish and brave and felt like something a girl says when she loves a thing more than her own survival. He wrapped his hand around my throat and squeezed until the room narrowed and then blurred. Father’s photo on the mantel split in two as my eyes misted. The deed crumpled under a heel that had never walked the length of this house at night to check windows before locking the back door.

“Stop.”

The room rearranged itself around that word. Even rage knows where to kneel.

Chike stood in the doorway. He had always moved like an apology. Now he moved like a man who had walked behind other men and learned where each kept his knife.

“Let her go,” he said.

Daniel sneered. “Stay out of this. This doesn’t concern you.”

“It does now,” Chike said, and the years of silence in our house shuddered at the sound of boundary.

“You’ve always been weak,” Daniel said, laughing that laugh men use when they are afraid they are about to discover what happens when they’ve misunderstood the world.

“Try me,” Chike said.

The room became a story I did not know how to stop. Daniel lunged. Chike met him. There is a kind of fight that belongs to boys in schoolyards and there is the other kind—men who know what it means to be tired. Daniel’s men turned when they saw their boss’s blood on the tiles and not mine. Lydia screamed my name as if my name were the one you shout when you want the police to come and believe you. I crawled to the corner and slid my fingers under the wrecked deed and lifted it with both hands like a body, smearing Father’s name with my blood because even when you are careful you touch what you love with your wounds.

Sirens began far and got close. Daniel’s men broke like a wave on a reef and ran. Lydia stumbled in heels that had only walked soft floors and shouted into the night about betrayal and family and custom. The police came in with guns drawn and eyes bored; then they saw the bruises that bloom fast on brown skin and the deed in my hands and the man in my brother’s hands and became men again.

In the hospital, light makes everything look clean. That is a lie doctors tell with brightness. Chike sat at the end of my bed looking like the kind of man who is angry with himself for arriving late to a fight he didn’t start. He had a split lip and a guardianship in his posture that would make wolves step back.

“He would have killed you,” he said.

“He would have tried,” I said, and the morphine made bravery cheap, but the words were true.

He touched the edge of the deed with one finger. “Father knew,” he said.

“He knew everything,” I said, and that is the most dangerous way to love a man.

The next morning a police officer with a long neck and raised eyebrows wrote notes in a pad that looked too small for the story it had to hold. “You will file charges,” he said. It wasn’t a question. “And you will move out,” he added like a coward offering you safety as an apology.

“I will move in,” I said. “Like a daughter who knows what the house expects of her.”

News in families spreads like groundnuts: fast and unexpected underfoot. The assault became a whispered thing. The court became a shouting place. Daniel told the police he had come to negotiate, that I had hit myself on a table corner, that he had only held me to keep me from hurting myself. Lydia cried in the witness room. Tears are a strategy some women inherit. She held a silk handkerchief Father would have hated for its fragility and dabbed nothing from her eyes.

“She manipulated Chief,” she told the magistrate, her voice softened by theatre. “She bewitched him into giving her the house.”

The lawyer we had grown up watching at Father’s side, the one with the glasses and the slow way of putting words into a room, cleared his throat and placed the signed, notarized will on the table between everyone like a judge placing a hand on a Bible. Witnesses spoke. Father’s driver, who had never before spoken more than thirty words in our presence, told the court about a night when Father stood in the courtyard and said, “This house is my daughter’s because she loves it,” and tapped the wall like a man confirming a lay of bricks.

Daniel tried to turn the river. He hired men to stand outside my door and make sure I knew they were there. He left notes slid under the bedroom door in handwriting that had once signed my report cards: Give up or die. He slashed my tires because there are men who think women only move when cars do. Chike slept on the sofa by the door with a cutlass leaning against the wall and a phone charged and ready. There is a way brothers can be fathers without making you small. He learned it.

Fear sat on my chest in the dark and did not leave when the light came. I brushed my teeth and the taste of blood returned even when there was none. I showered and Father’s voice whispered protect it in the steam. I put on a white dress one morning and took it off and put on a black one because I did not know how to be visible without feeling like a dare.

But every time I looked at the house—the way sun found the curve of the banister at five in the evening, the chip in the green tile on the seventh step where Father had dropped a hammer when he’d insisted on hanging the family photos himself, the section of wall by the kitchen door where Mother had marked each of our heights with a pencil every year—I remembered why paper matters. Why he had given me a thing that was not only walls, but instructions.

The judge read the ruling in a voice that made me wonder if he had daughters. The house legally and irrevocably belonged to me. Daniel was guilty of assault and attempted coercion. His sentence was not long enough to fill the gap between what he had tried and what he had done, but the clang of the cell door in my memory was louder than Lydia’s vile promises at the courthouse steps.

“You will regret this,” she hissed, and for a moment I felt sorry for her because regret is a house worse than this one when it falls into certain hands.

When the court emptied and the crush of curious bodies left only our small family, Chike stood beside me at the top of the courthouse steps and said, “We will paint.” He meant the walls and the story.

We did. We turned Father’s sitting room into a place where we could sit without waiting for shouting. We hung the photos back up and added one of Father smiling with a fish in his hands so big you might have thought the picture a lie if you didn’t know the river. We planted bougainvillea to climb the back wall because Mother had loved pink and because I wanted the house to be able to defend itself with thorns as well as laws. We changed the locks and hired guards not because houses need guards but because men with bruised pride arrive with numbers.

At night I woke with my heart jumping like a goat and his fist in my face. It took weeks to learn that when a door closes in the night it is the wind and not a brother. I learned the way a house breathes when you are the only one inside. I learned where the floorboards do not care if you step on them loud or light. I learned the turn of the key that will forever feel like a prayer and a punishment.

Grief is a place you get used to living in. Fear is a place you learn to leave. Revenge is a place you visit and tell yourself you do not live there while you make tea in its kitchen.

While curtains dried on the lines in the courtyard, I started to dig.

Part 2

There’s a bitterness that tastes like medicine on your tongue when you take it the first time and like candy when you take it the fourth. I told myself I wanted justice. In the dark of early mornings with ledgers spread on a table and my laptop casting a blue light on my fingers, I wanted more.

Daniel had always been certain the world would let him bend it. He had made a living bending men with poorer handwriting and less charm. But paperwork is a country with its own border guards. He had drivers with double payrolls and contracts that began in one mouth and ended on another. Lydia had collected the sheen of life like other women collect bracelets—shopping trips in Lagos and dinners in Accra and photos tagged with locations meant to make other women jealous. She believed she was due. They always do.

I called in markers quietly. A contact in customs owed Chike a favor after a night our second brother had fixed his Land Cruiser on the side of the road with nothing but twine and a mechanic’s prayer. He sent me scanned bills of lading with numbers that did not square to tax receipts. A clerk at the city planning office had a mother whose dialysis we had paid for after the clinic’s generator failed; she pulled every approval Daniel’s firm had sailed through and laid the stamps side by side. A banker who had closed Father’s first big loan and cried into my hair at the wake showed me the shape of accounts Daniel had opened under a cousin’s name.

Piece by piece, I built a map of a man who thought fences were for other people.

We did not go to the police. We went to the places that would hurt him the same way his fists had hurt me: his hands. We spoke to suppliers and “accidentally” let them know about invoices a man of honor would not refuse to pay. We whispered in the ears of partners who had wives tired of hearing Lydia’s laugh. We had photos. We had receipts. We had Father’s name and we were not afraid to stand over it like a roof.

When Daniel came out of prison, he was a smaller man in the way men who have had to line up for soap become: suspicious of the air, of anyone smiling; his hair cut too close against his skull; his mouth forever ready to defend. He went to his office and the locks turned under his key like we had rehearsed it. He called Lydia and she didn’t answer. She had found another empire to decorate.

He came to the house once. The guards did not let him through. He stood on the road shaking his head, looking up at a balcony where Mother had once stood and waved to him when he came home late from a run with his hands out, apologizing to a woman who would always forgive him. He sat on the bonnet of his car and stared until I walked to the gate. It felt childish and cinematic and exactly like the moment I had told myself would never come.

“You did this,” he said.

“You did this,” I said back.

He laughed, and if stone could laugh that is what it would sound like. “You think the house will save you?” he said.

“It already did,” I said.

He didn’t come again.

People asked why I had fought so hard for a building when there were other places a woman could live. You could let him have it, they said. You could buy a better house, higher walls, softer floors. You could stop being a target. You could rest. Invite your mother into your new kitchen and close the old door on the old ghosts.

But our father taught us that a house is not only a roof. It is a story. If I had given him the deed, I would have given him our name, and a story warped in the mouth of a man who believes owning is the same as deserving becomes a story that teaches our children the wrong lesson about love. I kept it because Father asked me to and because Mother’s sigh in the afternoons when she put the kettle on sounded like a promise.

Chike married a woman with eyes like early rain and a scatter of freckles that made him smile without knowing he was doing it. They had twin boys who learned to run in the courtyard in a year when the bougainvillea began to climb higher than any of us. The twins pointed to the pencil marks on the kitchen wall, where the heights of our heads and years had been recorded for almost three decades, and demanded equal treatment. We obliged. You add marks to a house, it becomes less likely to let itself be sold for parts.

I started a small school under the trees in the season when the harmattan dust made breath thin. It was not a school anyone would write newsletters about—the children of drivers and yard boys and market women who sold secondhand shoes; the children of women with grandmothers who had never learned to sign their names. We spread mats in the shade and wrote letters in the dirt and passed around a book like a holy thing. Wealthy men have always used their houses to launder legacies. I decided to use mine to wash children’s hands.

When I moved through the rooms alone, fear receded in a way that did not announce itself but measured itself in the quiet places in your head where you used to rehearse escape. I learned to open doors without listening first. I learned that the sound of a lizard dropping from a wall onto tile is not a man’s footfall. I learned that anger can live under your bed and you do not have to feed it every morning.

One Sunday afternoon, when the light outside was the kind that makes every tree look like the kind of tree you imagine when you are small, Lydia arrived at the gate. The guards called my phone and I stood at the upstairs window and watched her through the bougainvillea. She had aged like a woman who did not know how to age—a little too tightly; hairline fighting; eyeliner fighting harder. She called my name with a tone that expected all doors to open.

I went down and leaned against the iron bars of the gate and looked at the woman who had told my brother to end me.

“I need to speak with Daniel,” she said, as if I were an address book.

“He does not live here,” I said.

“He must sell this house,” she said, surprise flashing over her face that the sentence didn’t cause the locks to comply.

“He cannot sell what he does not own,” I said.

“You think you won?” she said, and her mouth curled in a way that told me that she only ever spoke sentiments in terms of winning.

“I think I lived,” I said.

She laughed and the laugh rubbed at the world like sandpaper. She turned to go, then called back over her shoulder, “He is your blood,” as if the word blood were a loyalty that could be made to erase history.

“So is mine,” I said, and went back into the house that smelled like clean tile and fried plantain and the lavender polish Chike’s wife used on the banisters because she said the smell felt like a good dream.

An aunt told me at a wedding that I had become hard. “You used to be soft, Adora,” she said, adding more jollof to her plate, and I smiled and said, “I am not the bed you can lie in when you don’t like your own.” She laughed and told me I sounded like my father and I took it the way she meant it: half insult, half applause.

The last time I saw Daniel he was standing outside the shop under the plantain trees drinking warm soda from a bottle. He had the look men wear when they think no one is watching them be small. He saw me and lifted his chin like a boxer who might yet get a last round. I nodded. It wasn’t forgiveness. It was gravity.

“What do you want?” he asked, though we both knew the answer to that question was embedded in the place I had kept.

“I want you to stop measuring love in deeds and start measuring it in days,” I said. He frowned because men who love paperwork have trouble with calendars you cannot stamp.

That night I sat at the dining table with the deed spread out under my palm. The bloodstain is there still, brown now and faint, the shape of a fingertip and a life. I thought of Father sitting in this chair with books open and numbers that were not just numbers but food and roofs and schoolbooks for other people’s children. I thought of Mother telling me to leave the casement window open during storms because the house needed to hear rain to remember where it was. I thought of the girl lying on the tile, head ringing and tongue swollen, and of the woman who had climbed to her feet holding a paper like an infant.

We held a memorial for Father that winter that was not about men in wrappers and speeches that sound like history. We lit lanterns in the yard and brought out bowls of egusi and fried fish. We asked each person who came to bring a story in the pocket of their dress or the heel of their shoe. Men who had never told the truth about anything told the truth about a man who had paid their VAT when the government came calling. Women who had never cried in front of anyone cried into palm wine and held their children on their laps so the children would remember laughter in their mother’s throats. We wrote down every story in a ledger and left the ledger open on the dining table for six nights for those who told their stories best alone after everyone had gone to bed.

In the quiet after, when the bougainvillea had decided to keep climbing into the eaves and the boys had been shooed off the banisters once more and the dogs had found the cool patch of tile to sleep on, I walked through the house and touched each doorframe. Some doors you close because the world is full of men who misunderstand the meaning of the word no. Some you open because you are not a house that was built to be only a fortress. Every wall I touched felt like a heartbeat.

People ask me if I would do it again—bleed on tile rather than move to a flat in a new estate with a generator that never fails and a swimming pool whose blue water looks like a calm I did not earn. I tell them what Father told me: house is not roof. It is reason. It is promise. It is a story that says a woman did not give up the thing her father trusted her to keep because a man told her the rules he likes best.

I am Adora, daughter of Chief Okeoma. Guardian of his house. Sister to a quiet man who picked up a chair and a knife and his courage and came to collect me when I was down. Survivor of my brother’s fists and my sister-in-law’s poison and the ache of being the person who must say no when all your life you were taught to say yes.

There are scars on my body that I will carry into every room I enter. I do not hide them. I lay out plantain for visitors and show them where the tile is chipped and let them see where blood became law. Out in the yard, the twins run under the trees and shriek at lizards and fall and rise and fall again and the jasmine climbs and the bougainvillea scratches at the boys’ ankles and leaves thin lines that look like cursive on their dark skin. They will have scars the way houses have stories—the way women carry crowns without glitter.

If Daniel ever comes again, if greed tracks the scent of this home like a dog and arrives at the gate with a grin and a lawyer on his arm, I will open the ledger and the deed and my mouth. I will stand in the place where Father taught me to put my feet when the river rose and say what he taught me to say: “This house belongs to the one who knows why.”

And if he says blood, I will hold up my hand and say, “Yes. Mine.”

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

It’s 7 AM and You’re Still Sleeping Get Up and Make Me Breakfast— My Mother-in-Law Screamed at Me… CH2

It’s 7 AM and You’re Still Sleeping? Get Up and Make Me Breakfast— My Mother-in-Law Screamed at Me… Part…

My Husband’s Family Called Me “Useless” — But My Dad’s Response Left Them Speechless. CH2

My Husband’s Family Called Me “Useless” — But My Dad’s Response Left Them Speechless Part 1 No one ever…

My Aunt Claimed I Owed Her $30K for “Raising Me” – The Judge’s Response Left Her Speechless…. CH2

My Aunt Claimed I Owed Her $30K for “Raising Me” — The Judge’s Response Left Her Speechless… Part 1…

My Husband Was Celebrating with His Mistress… So I Arrived with Her Fiancé. CH2

My Husband Was Celebrating with His Mistress… So I Arrived with Her Fiancé Part 1 What would you do…

Abandoned and erased by family, I returned after 9 years. Mom snapped: ‘Why is this failure here?’ CH2

Abandoned and Erased by Family, I Returned After 9 Years. Mom Snapped: “Why Is This Failure Here?” Sister Smirked: “You…

My brother’s fiancee slapped me in front of 150 people at their wedding. CH2

My brother’s fiancée slapped me in front of 150 people at their wedding because I didn’t give them my house….

End of content

No more pages to load