Dad Mocked Me for Studying 9 Languages—Then My Commander Said 6 Words. He Went Pale…

Part One

They say rooms have memory. Fort Belvoir’s main hall remembered more rank than truth. The carpet was too quiet, the coffee smelled like policy, and the applause was the kind that had to be told when to stop.

I sat three rows back in a plain uniform—no stripes, no ribbons, nothing that would let a stranger guess my weight in any room. My badge said LANE, B. If you looked closely, you’d see the Defense Intelligence Agency insignia and a clearance level that could buy a new identity. If you looked at me the way I’d been taught to look at people, you’d see a woman who had learned to put her center of gravity lower than the people around her, who spoke with a voice designed to travel further than a whisper but never become a headline.

Two seats in front, my father’s shoulders were squared like parade rest had calcified there. Colonel Thomas Lane, retired. He wore a suit he’d had tailored ten pounds ago and a gaze he’d honed for four decades—scanning, dismissing, commanding. I hadn’t seen him in almost three years. Not since he told me in a kitchen with a dull knife and a sharp tone, “You’re wasting your time with these languages, Bridget. Nine languages won’t make you a soldier.”

Those words had stuck like a burr under my ribs. I’d learned to run with it.

The master of ceremonies cleared his throat. “Today, we recognize a member of the DIA whose work has directly prevented international conflict in five theaters of operation, who has served in silence, who speaks nine languages fluently.”

My father’s scoff wasn’t loud, but it was built to carry. “Nine languages won’t make you a soldier,” he muttered to the man beside him. I watched his profile—the familiar angle of a jaw that had been a wall my whole childhood. Somewhere in my shoulder blades, a chord that had been tuned too tight for too long vibrated.

The podium mic popped. The master of ceremonies stepped back. My commander stepped forward.

General Marcus Latimer looked like the word “briefing.” He did not consult notes. He did not smile. He looked out at the room and said six words that bent the air.

“We need Ghost Walker in the room.”

Nobody clapped. A murmur moved like wind through a wheat field and then stopped when nobody wanted to be the last voice caught standing. People turned their heads, some toward the door, as if a myth were about to walk in from outside.

I stood up.

Head turns clicked in a wave that reached my father last. He turned, slow enough that I knew he was giving himself a second to choose a face. He didn’t find one. His eyes widened, only a fraction. He pushed himself to his feet because men like him are trained to stand when something bigger than them stands in front of them.

I passed him in the aisle and didn’t pause. He smelled like aftershave and a memory that had been filed but not processed. At the podium, General Latimer nodded once, not to me but to the moment. I returned the nod and faced the room. Fabric shifted; a hundred spines straightened by reflex. The silence had weight. It pressed equally on pride and shame.

My father held my gaze from the VIP row. The corner of his mouth moved like a muscle learning a new task. He had told me once that the Army made him into a man. It had made me into a shape he didn’t have a word for.

They didn’t announce my medals because I didn’t have any. They didn’t list my missions because you don’t list things you deny exist. They said my callsign—the one whispered in SCIFs and painted on no wall—and it did more than a ribbon rack ever could: it pulled the right people to attention and left the wrong ones still sitting, wondering what they’d missed.

I grew up in a house where silence was a tool. My mother’s lupus taught us to measure the day by sound—the good days when you could hear the kettle, the bad days when breath was the only thing and it was a small, fierce thing. My father came home every night at 1800 like a storm front, and if I was lucky, he said three sentences to me that weren’t orders. He loved in starch and inspection. When I was nine, I learned there are languages where “please” is implied. English wasn’t one of them in our kitchen.

I found my first language outside of that house on a shortwave radio with a missing knob. I learned to hold a frequency the way some kids learned to hold breath under water. Italian weather reports, German love songs, a protest broadcast from a city I couldn’t find on a map. I learned that meaning traveled on waves you couldn’t see, and that if you listened long enough, you could hear the shape of a lie.

At 12, I said a full sentence in French at breakfast. My father didn’t look up. “That won’t get you out of push-ups,” he said, and bit into his toast like it had disappointed him. I learned Russian in my closet with a flashlight and a smuggled cassette. Arabic at the laundromat from a woman who ironed my school uniform and taught me three ways to say “courage” without using the word. Farsi from an old man who ran the corner market and had a son who hadn’t written home in five years. Spanish from a janitor who listened to boleros on a transistor radio balanced on a bucket.

By sixteen, I could ask for help, directions, and forgiveness in eight tongues. In my house, I used only one.

He put my acceptance letter on the counter beside the grocery list with a grunt that could have meant anything. I folded my shirt sleeves and learned how to salute men who earned his version of praise with bullets and bruises, and then I went where he wouldn’t think to look for me. I went to the Defense Intelligence Agency.

The first thing they gave me was a badge and a lock. The second was a desk without a plaque. The third was a headset with no comfort setting. My title said “linguistic field support specialist.” It did not say “we are going to build you into a weapon we can deny.” I learned to step off planes in places my father used his finger to point to on the map. I learned to say “stop” in a dialect that would stop men who would not hear it in their own language. I learned that fear has a cadence, that greed elongates vowels, that regret arrives after a pause where a person should have inhaled.

They noticed. Not publicly. Nobody sent a cake. They sent me coordinates.

Syria should have been routine: humanitarian logistics threaded with secrets like wires under tile. The voice on the comm wasn’t routine. It knew my real name. That is a kind of intimacy you don’t allow in my line of work. It shouldn’t have been possible. It was. Everything unraveled: informants vanished, our safe house burned down to a metal skeleton, and Staff Sergeant Keller bled on my scarf while I counted his breaths in Arabic so he wouldn’t die in English.

Back in Stuttgart, they asked me if I’d been careless. I told them the truth: no. They told me policy and made me stare at a potted plant for six hours under the fluorescent hum that makes men confess their sins to ceilings. I learned that the system can be deaf to the person it trained to listen.

Then the call came from a friend who had stayed kind despite the building. “It’s layered,” Evan said. “The signature in the breach? It matches a proprietary cipher from Project ALTO.”

“ALTO,” I said. The name had been a rumor in our house the year I graduated high school. My father had been proud of it the way other men are proud of their first sailboat. Encryption licensing. Joint task force. Men shaking hands in rooms that smelled of coffee and test code.

He sent me the document. My father’s signature curled across the approval line like a snake that had eaten a bird. The metadata said he had signed off from a private consultancy at 0213 hours on a contract that gave a small shell company called Redshore Analytics authority to install a secondary lattice in our signal chain. It wasn’t proof of guilt. It was proof of access. It was ash where smoke had been.

I built a report without my name on it and dropped it through a channel men with practical haircuts pretend they don’t know exists. Oversight Compliance Unit Three read it and said everything without adjectives. A court summons is just nouns and verbs.

The invitation to Fort Belvoir landed two weeks later. I did not ask my father if he’d gotten his. He had. I could tell because my stepmother posted a photo of his suit with the caption “proud day” and three flag emojis. I tried to imagine saying to him, “Dad, I learned to say ‘I miss you’ in the dialect of a man who had no reason to trust me, and he gave me the information that pulled six soldiers out of a cell before the first sunrise we’d never let them see.” I put the thought in a drawer. I put on my uniform.

I stood up when General Latimer said my name without saying it. My father stood because his training told his legs to. I did not look triumphant. I stood the way I had taught myself to stand: low center of gravity, breath easy, ready to move without making noise. It is very hard to kill a ghost. It is harder to shame one.

Nobody added me to a program after the fact. Nobody scrambled to assign credit. The men who had burned my name had to sit in their chairs and watch me be myself in front of the one man I had wanted to be myself in front of since I was eight and put my ear against a radio that sang in German about a love that felt like salt water and horses. The boy in that song had said “ich will dich” and meant it. My father had said “you’re wasting your time” and meant that too. There are things you can’t translate.

He didn’t approach me after the ceremony. He walked into the parking lot and called someone named Charlie and said “Ghost Walker” like he was trying on a coat he thought he’d been too good for. “If she was in the room, the mission lived,” Charlie said. How lucky for me that Charlie had simpler math.

I didn’t get flowers that week. I didn’t get a cake this time either. I got an email with no subject line that said, “If I sign a confession, will you go public?” I stared at it a long time. It was a confession the size of a pinhead. He hadn’t asked how I was. He hadn’t asked what I’d risked. He hadn’t said “I’m proud.” He had asked me to protect his story. I wrote back one word: “No.”

He never replied, but I got a notice that someone had accessed a file in a place I didn’t realize was still synced to my account—the place I keep the cipher and the Redshore contract and the messages that prove what can be proven.

He walked into a room a week later and told the truth to men with pens who would write down enough of it to satisfy written procedure and save as much of his good name as could be saved by daylight. “I authorized a contractor I didn’t vet,” he said. He said nothing about me. He told oversight the part that was his to hold and then asked one thing: “Keep my daughter’s name off every record.”

The sanction fell in private. No press release. This wasn’t that kind of war. They took his clearance and the revolving door that had turned him into a consultant slowed to a stop. He mailed me his West Point pin in a brown envelope with no note. He had once told me a signature was a man’s honor. He sent me the thing that said he had one and let me decide whether to believe him. I do not wear it. I think about it.

When the assignment came to step away from field work, nobody forced me. I chose to. I was tired of being a razor used in darkness and then put back in a drawer. The new job didn’t have a callsign. It had fluorescent light and a budget and a title: Director of Strategic Language and Cultural Intelligence Training. It had a whiteboard. It had a door with a small metal plate someone else had had engraved without telling me.

THE GHOST WALKER ROOM.

I ran my fingers over the letters the day I walked in. Not to feel important. To feel seen. It wasn’t for me, anyway. It was for the nineteen-year-old second lieutenant who would walk past it and decide that learning Dari wasn’t weakness. It was ammunition. It was for the Master Sergeant from Savannah who didn’t want to admit he’d misread a man’s eyes because he’d never learned the difference between “shame” and “fear” in that dialect. It was for the analyst whose report would be read by a person like me, and whose courage to write the sentence “This is not noise” might keep a convoy alive.

We built a listening lab. We wrote a curriculum that taught men who thought they were warriors to sit still for five minutes and hear the sound of a lie. We ran simulations with real audio spliced into fictional context, because truth under pressure looks different than truth in a classroom. We made them translate their own doubts into new rules of engagement: “Wait one more beat”; “ask the woman in the back”; “notice who laughs”; “ask what the joke is.” We taught them to hold a glass by the stem so they don’t leave prints they don’t want to be matched to a room they don’t want to be in.

A commander asked me one night after class, “Did you really serve under the name Ghost Walker?” I asked him a question instead. “What do you think it means?” He said, “It means you saved people without needing to be seen.” I said, “Then keep believing that.” He saluted. I did not. Some gestures swell too easily.

There is a photograph pinned above my desk. It came in a small, unmarked box the week after the metal plate went on the door. A little girl with a too-big book in her lap sits on linoleum with her mouth open mid-sentence. My mother must have taken it before her voice left the house. The paper it came with said, “You once said you wanted to change the world with intelligence. Maybe you did.” He did not sign it. His silence finally translated.

When I go home now, the house I grew up in looks smaller. It always does when you stop being the child in it. He is out west in a garage, rebuilding a Cessna with a neighbor he calls “kid.” He will tell that kid stories about medevac pilots and hard landings and a daughter who speaks nine languages and taught him that a confession can be an act of war, and an act of love, if you choose it. He will not say my callsign. He doesn’t have to.

If you asked me the six words I remember from that day, they are not the ones my commander said. They are the ones the room didn’t say but learned anyway: “She was in the room; we lived.”

Part Two

The lounge after the ceremony smelled like coffee and evaluation. I poured myself paper-cup courage and stood by a poster about cyber hygiene, all teal and verbs. Behind the vending machine, the first whisper breathed a theory and waited for oxygen. “Ghost Walker? Please. They put a code name on a translator and act like it’s combat.”

It was said by a man who used adjectives like brass. Another smirked for the benefit of the smirk next to him. “Marketing, man. Tactical branding. Put linguistic lipstick on a pig and call it elite.”

“Classified isn’t unverifiable,” Major Lawson said, without lifting his eyes from his cup. His baritone slid under the noise like a river under ice. They shifted. Men like the noise of certainty. They hate the sound of being asked to doubt themselves.

I felt no sting. I had spent years as their blind spot. You cannot shame a shadow. But as I stood there, a younger officer—Ramirez—approached like he was stepping onto a different kind of floor. “Ma’am,” he said, awkward, sincere. “Your Baltic packet saved us three months of tail-chasing. It was the way you flagged the pause before the ‘yes.’ We almost missed it.”

“People always almost miss the pause,” I said. “Good instincts don’t replace paying attention.”

He nodded, grateful that the girl with the ghost for a name gave him a sentence he could put in his pocket. He left. The whisperers noted the direction of respect. Their smirks solved for the lack of company and moved on to safer topics like drones and budget cycles. I drank my coffee and graded their posture. People who can be taught look at doors like they might be used for something. People who can’t look at posters like they might teach themselves.

My father didn’t call for three days. The fourth, he sent an email with no signature because names were losing function for him. The sentence—If I sign a confession, will you go public?—was a hand held out and too late. I wrote “No” and hit send. Not because I wanted to threaten him. Because I didn’t need to. The room had done what rooms do when you put the right truth in them. Men who had hidden behind classification wrapped their own silence around him and called it “ethics review.”

He walked into a secure hearing with a haircut and a binder. He told the truth in the narrow sense. “I authorized a contractor I didn’t vet.” He did not say, “I authorized it because an old friend asked.” He did not say the word “daughter.” He did say, “Keep her name out of it.” It was the only time in my life he prioritized my safety over his biography. The DIA accepted his sentence without sentencing him—no clearance, no consultancy, no press.

He mailed me his West Point pin. It landed in a pile of catalogs on my porch like a small apology trying not to look like one. I didn’t clasp it on. I put it in the drawer with the Redshore contract and the Syria cipher. Legacies can live beside each other without sharing a hook on the wall.

“How did you learn to hear people?” a recruit asked me in the second month of the Listening Lab. He was the kind of student who needs rules written on the board and also the kind who will one day break the right one to save someone. “I grew up in a house where the loudest thing was disappointment,” I said. “You learn to parse tiny changes in air pressure.”

We built modules that felt like field work. Not “how do you say ‘where is the hospital’” but “what does it mean when a man says ‘I can’t find my cousin’ and the room goes quiet?” We taught them Slavic code-switching, Pashto honorifics, the difference between Levantine Arabic “ma biddi” and the way a father says “no” to his son when he means “don’t make me lose face.” We played audio of a negotiation that had almost gotten someone executed and asked them to find the moment the first lie landed, not in the verb, but in the breath.

The brass toured the lab and nodded like they were considering buying it. A colonel read the syllabus and said, “Feelings aren’t intelligence.” I said, “You have men who can smell a bomb through six inches of sand because the vapor is different by a hair. This is that, but for words.” He blinked the blink of a man who has learned to accept new tools if you make them sound like old ones. “Carry on,” he said. “Roger,” I said. He left believing he’d commanded something.

I drove home that night past a strip mall and a church with a sign that said, “Be still and know.” Being still had never been my strength, but knowing had paid my rent. On my porch sat the small box with the photograph of the girl on the linoleum. I laughed alone in my kitchen—short, startled. “You kept something,” I said to the box as if it were a person. He had never kept any of my school projects. He had kept this. Sometimes men change by ounces. Sometimes that’s all you get before the story ends.

I began enforcing boundaries like Rules of Engagement. My stepmother invited me to Thanksgiving and asked if we could avoid politics, religion, and work. “We can talk about cranberries,” I said. She said, “We’re having stuffing,” and we both laughed to fill in the trench. I went. I brought a pie. My father pulled my chair out like a gentleman from a 1950s film. He said, “I heard your unit opened a new wing,” and did not say “Ghost Walker.” He asked for salt. He did not ask for forgiveness. I did not offer it. The turkey was dry. We survived.

The first holiday after the ceremony, I received two cards. One from a captain under my command who wrote, “My wife says I stopped shouting at the kids. Your module on silence did that.” One from my mother’s sister with a photo of my father and me in the backyard when I was five, him bending down to tie my shoe with an expression I had never seen him wear since. “He was proud,” she wrote. “He just didn’t know how to hold it without crushing it.” I pinned the photo on the corkboard next to the lab schedule. I wrote beneath it in thin black marker: “Hold without crushing.”

Emma turned seventeen and asked if she could intern in the lab for a summer. “You’ll hate it,” I said. “It’s slow. It’s precise. You’re a comet.” She said, “I can slow down,” with the stubborn earnestness of someone who hasn’t had to yet. I said yes and wrote her a reading list that began with “Listening is a Revolutionary Act” and ended with “Phone Trees Save Lives.” She sat in the back of the room for two weeks and then raised her hand and said, “That woman isn’t saying ‘I don’t know where my husband is.’ She’s saying, ‘I know and you will kill him if I tell you.’” I made a mark in my grade book that wasn’t a grade. It was a note for a future version of me, the one who would be old and tired and in need of someone to continue being irritatingly accurate.

One afternoon a year after the ceremony, my father left a message with a mutual friend: “Tell her I saw the door.” He meant the metal plate. He meant the room with my callsign on it. He meant, “I’m still a man who uses nouns instead of feelings,” and also, “I drove three hours and stood in a hallway by myself to look at a word.” I considered calling him back. I wrote his number on a yellow sticky note and stuck it to the bottom of my computer monitor where the dust lives. The next morning I threw it away. I wasn’t being cruel. I was maintaining a line I’d drawn with my own blood.

The last time I used my callsign in the field—on paper it was never me—I did it to sign a memo to myself. “Stop carrying his map,” I wrote. “Make your own.” It sounded like therapy. It was tradecraft. If you live in the story someone else wrote for you, you will miss the door that leads out. If you write your own, you can build a room with a plate on it.

When the letter from the Office of Inspector General arrived confirming my father’s statement and the sanctions, I put it in the drawer with the pin. I did not read it twice. Re-living has never been a productive habit for me. I closed the drawer and went to class and made thirty soldiers listen to a grandmother from Homs talk about bread for five minutes. At minute three, one of the majors began to cry without knowing why. I said, “That is intelligence,” and erased the board.

In the end, those six words did exactly what I needed them to do. They translated me for a room full of men who had only learned one language of respect. They stood. He stood. And then they sat down again—this time differently. The weight moved. You could feel it in the carpet.

If you’re looking for the point in this story where my father and I embrace in a parking lot and he says “I’m sorry” and I say “I love you” and he says “I always did,” it isn’t here. I loved him when he was wrong. He loved me when it was useful to a story he told himself about the kind of daughter he should have had. He tried to fix one thing he had broken, and I let him. That is not a reunion. That is a ceasefire. Sometimes ceasefires last long enough for people to forget the sound of explosions. That’s enough.

Men in the lounge will still whisper sometimes. Women will roll their eyes sometimes. People with no skin in the game will write essays about “soft power” like they invented listening. But when a captain in a convoy pauses because something in the way a man said “fine” sounded like a lie and he radios command and five lives make it home because he waited three seconds and the blast went off where he would have been—that’s the work. He’ll never say my name. He’ll say, “Something sounded off,” and the lieutenant next to him will say, “Thanks, man,” and write it up as good instincts.

I know what to call it. I call it a language I taught him in a room with a whiteboard. I call it the sound of a girl who sat on a kitchen floor with a shortwave and learned to hear her way out.

Sometimes I still dream in Greek. Sometimes I dream in the silence of my father’s house. Sometimes I wake up and don’t know which is which. On those mornings, I make coffee and open the drawer and touch the pin and the paper and every unsent sentence I have folded into myself. And then I go to work in a room with my name on it, and teach a soldier how to tell the difference between someone who wants to kill him and someone who wants to survive him. When he gets it right, he doesn’t applaud. He nods. That’s the only recognition I have ever wanted.

We need Ghost Walker in the room, the general said. We needed her then. We need her now. I’ll be there—sometimes in person, sometimes in the minds of the people I trained—every time someone decides to listen before they shoot.

Nine languages didn’t make me a soldier. They made me the person soldiers need most when silence is all you’ve got left. And the man who taught me to stand at attention finally learned to stand still long enough to see that.

That’s enough. That’s everything.

END!

News

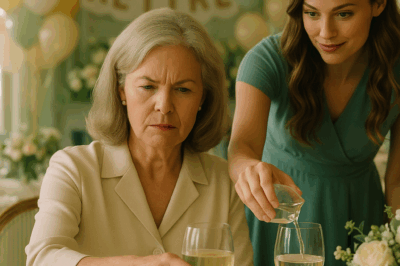

At My Retirement Party, My Daughter In Law Slipped Something In My Drink — So I Switch Glasses. CH2

At My Retirement Party, My Daughter In Law Slipped Something In My Drink — So I Switch Glasses. Part One…

“Grandma, My Parents Are Going To Take All Your Money,” My Granddaughter Said. Then I Made My Plan. CH2

“Grandma, My Parents Are Going To Take All Your Money,” My Granddaughter Said. Then I Made My Plan Part One…

At Midnight, My Stepfather Beat Me—My SOS Text Brought the Special Forces to My Rescue. CH2

At Midnight, My Stepfather Beat Me—My SOS Text Brought the Special Forces to My Rescue Part One I woke…

The Day Before Brother’s Wedding, When I Said ‘I Can’t Wait for Tomorrow,’ My Aunt Froze in Shock.. CH2

The Day Before Brother’s Wedding, When I Said “I Can’t Wait for Tomorrow,” My Aunt Froze in Shock… Part…

My Ex Married His Dream Woman Right After Our Divorce—Then I Saw Her Face And Knew Everything. CH2

My Ex Married His Dream Woman Right After Our Divorce—Then I Saw Her Face And Knew Everything Part One…

My Daughter-In-Law And Her 25 Relatives Are Coming For Christmas? Perfect — I’m Traveling. They Can… CH2

My Daughter-In-Law And Her 25 Relatives Are Coming For Christmas? Perfect — I’m Traveling. They Can… Part One The…

End of content

No more pages to load