Dad Gave My College Fund to My Stepbrother’s Startup – The Email I Forwarded Changed Everything

Part 1

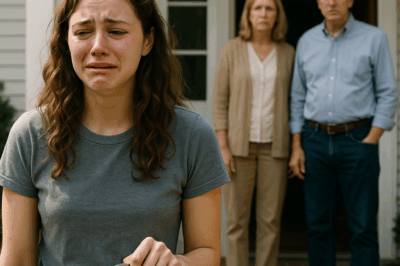

“Your stepbrother needs it more,” Dad said, sliding a stack of withdrawal papers across his mahogany desk like he was recommending a new brand of paper towels. The afternoon sun slanted through the home office blinds, striping his degrees and awards in gold bars that made them look like shields. I used to be scared of this room when I was little—its heavy smell of leather and cologne, the bookcases that climbed like cliffs, the door that always closed behind me with a hush that meant I should be small and polite. Today, the room felt… small. Or maybe I just wasn’t small anymore.

I nodded as if I’d heard this kind of logic all my life. In a way, I had. While he talked about sacrifice and family vision and Ethan’s “once-in-a-generation” entrepreneurial gift set, I pulled out my phone, opened the email from three years ago—the one he’d written after Mom’s funeral—and hit forward. To: Grandpa. Subject: Re: Leila’s education fund—promise.

I heard the whisper-buzz of Dad’s phone on the desk at the same moment mine whooshed. He didn’t check it. He was on a roll.

“You can take loans like everyone else,” he said, generous as a banker on a billboard. “Ethan’s building something real. It’s an investment in the family’s future.”

“Whose family?” I asked, and my voice surprised me because it was steady. I took screenshots of my bank portal—my mother’s education trust, the line that had always said “untouchable,” the balance that should have read $50,000 and now didn’t. I saved each image as carefully as you fold away old letters: with the knowledge that the paper is proof.

Ethan sat on the leather couch in the corner, the glow from his laptop flattering a face I’d known since I was thirteen and he arrived with Linda and a new set of rules I hadn’t voted on. He was typing hard, probably drafting a deck for the app that would change the world. He’d had so many world-changing apps. Uber for dogs. Airbnb for storage units. Blockchain for—what was it?—farmers. He never ran out of buzzwords, only runway.

“Leila, don’t be dramatic,” Dad said, mistaking my silence for shock rather than strategy. “You know how promising Ethan’s work is. Sometimes we do hard things for the greater good.”

“My mother,” I said, and the laugh that came out of me had a sharp edge. “She set that fund up when she was dying. She made you promise.”

“Circumstances change.”

“Ethan has burned through two hundred thousand of your money already,” I said, keeping my tone even though my hands were shaking. “His last three startups failed.”

“Those weren’t failures,” Ethan said without looking up. “They were learning experiences.”

“This time is different,” Dad added, a duet.

“Like the fitness app that was going to revolutionize exercise? Or the social platform for pets?” I tilted my head. “Or was it the farmer-blockchain? I can’t keep up.”

“You wouldn’t understand,” Ethan muttered, flush rising. “You’re not an entrepreneur.”

“No,” I said. “I’m just the straight-A student who got into MIT.”

Dad’s jaw worked once. “That’s enough. The decision is made. The transfer’s done.”

“All of it?”

“We left five,” Linda said from the doorway, her smile as polished as the marble foyer. “For books and things.”

“Books and things,” I repeated. “Thank you for letting me know.” I stood. “I assume you won’t be paying for housing, either.”

“Don’t be ridiculous,” Dad said, as if I’d suggested we sell the house. “Take loans. Everyone does.”

“You had loans,” I said softly. “You also had parents who didn’t steal your college fund.”

“No one stole anything,” he snapped. “That money is family money. I decided how best to use it for the family.”

I slid my phone into my pocket. “Family money. Family decisions. Got it.” I stepped toward the door. “By the way—when’s the inheritance meeting? Grandpa mentioned next Tuesday.”

He blinked. The veneer cracked just enough for me to see the wood beneath. “What inheritance meeting?”

“The one where Grandpa distributes Grandma’s estate,” I said, as if I were trying to help him find a misplaced umbrella. “He texted me last week. Said he wanted all the grandchildren there.”

In the hush that followed, his phone buzzed again. Linda turned to him, voice like a knife slipped under paper. “What inheritance meeting, Richard?”

I left before he could answer. In the hallway I heard her ask again, sharper. My name—Leila—floated after me once, then died in the foyer’s echo.

The drive to Grandpa’s took two hours. I used the time like a bandage and a blade: I pressed it against the hurt and cut away the second-guessing. The email I’d forwarded was dated three years ago, from the week after Mom’s funeral. He’d written it when he was scared Grandpa would cut him off for remarrying so quickly. He swore—swore on Mom’s grave—to protect my education fund, to treat it as sacred, untouchable, mine. Grandpa had replied with an old-man joke about how you shouldn’t swear on anything because words should stand on their own. And then he’d saved it. Grandpa saved everything.

He opened the door before I could knock twice. “Leila Bird,” he said, using Mom’s nickname for me. He smelled like coffee and cedar. His cardigan sagged at the elbows. I wanted to fold into him like a tired napkin. “Figured you’d be coming by. Got your message. Got more than that.”

He led me to his study. It was smaller than Dad’s office, and warmer. The papers stacked on his desk looked less like a fortress and more like a life. “Been digging,” he said, tapping a manila folder with one knuckle. “Interesting stuff.”

I told him everything. He listened like the old do when they’ve outlived a few illusions and learned not to interrupt a truth while it’s making up its mind.

“Your grandmother,” he said when I was done, “came from nothing and wasn’t ashamed of it. She liked to say poverty taught her to read contracts. She left very specific instructions about her estate. Especially for education.”

“Dad said there wasn’t much left,” I said. “That most went to medical bills.”

Grandpa snorted. “Your father says a lot of things. Like when he promised to protect your mother’s money.” He slid a paper across the desk: a printout of the email thread, highlighted in yellow like sunlight. “Like when he swore Linda was temporary.” He lifted his eyes. They were sharp behind his glasses in a way that made me feel both protected and called to account. “Like when he said Ethan’s failures were bad luck.”

“You know about Ethan’s startups?”

“I know your father has been funding them,” he said. “What I didn’t know was where it all came from until now.” He tapped the folder again. “Leila, your fund wasn’t the first. Your cousin Jeremy’s education trust was… rerouted two years ago. ‘Family emergency,’ your father said. Jeremy’s parents were too proud to tell me until last month.”

“How much?”

“Thirty,” he said. “Plus your fifty.” He leaned back. “Plus some creative accounting at your father’s company that looks like someone tried to wallpaper over mold.”

“What are you going to do?”

“Me?” He smiled, and it wasn’t warm. “Nothing that your grandmother didn’t already plan.” He handed me a photocopy of a page from her will. The legal language was a forest, but one paragraph was a road, highlighted bright: Any beneficiary who misappropriates, misdirects, or otherwise violates fiduciary duty regarding family funds forfeits their inheritance, with their portion redistributed among remaining eligible beneficiaries.

“Dad violated fiduciary duty when he took my fund,” I said.

“And Jeremy’s. And perhaps others,” Grandpa said. “I’m still untangling the knots.”

“How much would he lose?”

“His portion?” Grandpa rubbed his jaw. “About two million. Plus his voting shares in the company. Plus the lake house. Plus his board seat.”

I sat down hard. The leather wheezed. Two million was a number that didn’t feel like numbers. It felt like choices. It felt like a winter coat, a mortgage, a dozen second chances.

“Does he know about the conditions?”

“He knows,” Grandpa said. “He just thought I didn’t have proof. He thought family would stay quiet.” He looked at the printed email again, then at me. “He thought wrong.”

My phone buzzed. Dad. Then Linda. Then Ethan. I turned it face down like it was something I didn’t want to see in daylight.

“I don’t want his money,” I said, voice smaller than I liked. “I just wanted mine. The money Mom left for me.”

“I know,” Grandpa said, and his voice gentled the way a hand settles on a shoulder to keep someone from stepping into traffic. “But actions have consequences. Your father has been playing with other people’s futures for too long.”

“What about Ethan?” I asked, and I heard the apology in my own question, its weft of old exhaustion. “He’ll blame me.”

“Ethan is twenty-eight,” Grandpa said. “He has an MBA and a genius for convincing other people to finance his experiments. Let him blame what he wants. Responsibility is a ladder. He can climb it, or he can stand on the ground yelling at the clouds.”

We ate spaghetti that night, Grandpa’s sauce simmered long enough to count as patience. We talked about anything but money: about Mom’s terrible piano lessons and my roommate’s obsession with competitive birding, about Grandma’s garden where tomatoes grew like jokes and sunflowers like confidence. After the dishes, he poured coffee into the mug Grandma used to claim even when the cupboard held six identical ones. “You’ll go to MIT,” he said, as if it were a simple logistics problem. “One way or another.”

“With what money?”

“Loans if we must. But we’ll find a better way.” He folded the photocopy of the will and slid it into a new folder. “Tuesday’s meeting will be… clarifying.”

“He wasn’t always like this,” I said, because grief is a habit and my mouth knew the old defenses even when my heart didn’t buy them anymore. “Before Mom got sick. Before Linda.”

Grandpa’s face softened, then hardened like cooling glass. “He was always like this, Leila Bird. He was just better at hiding it. Your mother saw the best in him, and she brought it forward. Without her, the worst had more room.”

Tuesday arrived like a dentist appointment: circled on calendars, preceded by dread, inevitable. The law office was all glass and chrome, a place where sound went to be disinfected. Ms. Patterson, the family attorney, had a handshake like due diligence. Dad arrived in a navy suit that had broadcast respectability at fundraisers for years. Linda’s heels claimed the marble with each click. Jeremy was there, and his parents, and three cousins I hadn’t expected to see. Ethan didn’t come. Maybe he thought the budget didn’t concern him. Maybe he didn’t like rooms where you couldn’t pivot the topic to a pitch.

“What is this?” Dad demanded, scanning faces for allies, then the door for exits. “Some kind of ambush?”

“A family meeting,” Grandpa said mildly. “To discuss your mother’s estate. And some irregularities.”

Ms. Patterson laid out the paper trail with surgical calm. The trusts. The transfers. The forged co-signatures that mirrored Linda’s hand a little too well. The way five different family accounts had found their path to Ethan’s failed ventures through a maze that wasn’t complicated enough to be clever.

“That’s ridiculous,” Dad said. “I’ve been helping family members in need. Investing in the family’s future.”

“With my son,” Uncle Marcus said, voice like a gavel. “Money meant for our children’s education.”

“It was temporary,” Dad said. “I was going to pay it back.”

“When?” Jeremy’s mother asked. “After which app?”

Dad looked at me as if this were my fault for not keeping something unpleasant under the rug. Linda’s voice rose a register. “This is Leila’s doing. She’s jealous of Ethan’s success.”

“What success?” I asked. “Name one profitable quarter. One investor who isn’t related by love or pity.”

Silence. It had weight in that room. It knocked diplomas askew in people’s minds.

“According to Mrs. Harrison’s will,” Ms. Patterson said, her glasses reflecting a grid of light, “misappropriation of family funds constitutes a breach of fiduciary duty. Mr. Harrison, you have forfeited your inheritance rights.” She paused. “Additionally, per clause twelve, your board seat is immediately vacated, and voting shares revert to the estate for redistribution.”

“You can’t do this,” Dad said. The gray in his face made him look older and, for a painful second, like the man Mom fell in love with before ambition taught him its favorite dance. “That money is mine. I’m her son.”

“You were her son,” Grandpa said. “You’re also a thief. The difference is now on paper.”

Linda started to say “lawsuit” and “elder abuse” and “you’ll hear from our—” but the words sounded like props in a play whose audience had already left. The rest was forms and signatures. Dad’s portion—two million so polite it wore a bow—would be divided among the grandchildren whose trusts he’d plundered. The company shares went to Uncle Marcus, the lake house to Aunt Sarah, the board seat to Jeremy. It was like watching pieces on a chessboard step back to their intended squares after someone had cheated a few moves.

“How do you feel?” Jeremy asked as we walked into the light-washed lobby afterward.

“Honestly?” I said. “Sad.” The word surprised me, but it was true. “I wanted him to choose me. Just once.”

“I get that,” he said.

My phone rang. The number on the screen said MIT Financial Aid. I almost didn’t answer. My hand did what old habits do—it lifted the phone to my ear like hope still lived there.

“Ms. Harrison?” the voice said, brisk but kind. “We’re calling to confirm we’ve received a significant donation designated specifically for your tuition and living expenses. It covers all four years.”

“From who?”

“The donor requested anonymity,” the voice said. “But asked us to tell you your grandmother would be proud.”

Through the glass walls I saw Grandpa speaking with Ms. Patterson, his profile stoic and a little tired, like a statue that had gotten up and done the hard work and would now sit back down. I closed my eyes. “Thank you,” I whispered to the phone and to the woman who still lived in all the contracts she wrote and the recipes she left unwritten.

That night, Grandpa sent me home with leftovers wrapped in foil and a note in his old blocky hand: You forwarded the truth. Sometimes that’s the most powerful lever. See you at orientation.

I put the note in my wallet behind the picture of Mom. For the first time since the mahogany desk, I slept.

Part 2

The fallout arrived in waves, as these things do. First the family group chat went quiet and then feral. Messages crackled with anger and defense and the kind of disbelief people use to bargain with reality. Linda’s texts landed hard and fast—You ungrateful child; You’ll regret this; You’ve ruined your father—until she remembered screenshots exist and switched to phone calls I didn’t take. Ethan emailed three lines: you don’t understand how startups work; family sacrifices; you’ve set us back years. I replied with one line: Debt owed is not a business model.

At home, the house’s echo changed. Spaces that had always reflected Dad’s voice learned the shape of his absence. A week after the meeting, he moved into the guest room over the garage while Linda “stayed with a friend to think.” The local paper ran a neutral piece about a “leadership transition” at Harrison & Co. The company holiday party was canceled “to focus on core initiatives.” Aunt Sarah texted me a photo of the lake house keys resting on her palm like a talisman. Uncle Marcus called to ask if I’d be interested in a summer internship in the audit department. “We could use someone who reads fine print,” he said, and I could hear the smile he didn’t want to name.

I packed for MIT with hands that still shook sometimes and a heart that didn’t. The anonymous scholarship—anonymous the way a weather pattern is anonymous even when you know where the wind is coming from—paid for everything. Books and things. Rent and ramen and lab fees and winter boots that didn’t pretend salt stains were a fashion choice. I sent Grandpa a selfie in my dorm: bare mattress, crooked poster, my grin. He replied with a photo of Grandma’s garden bench, empty, early-morning dew on the slats. The caption: She’d be sitting here smiling until her cheeks hurt.

Orientation at MIT is a whirl: lanyards and acronyms, a scavenger hunt that ends in a lecture hall where you realize “imposter syndrome” isn’t a syndrome so much as a schedule. I loved it like a person loves sprinting after they remember how to breathe. I loved the problem sets that made my brain feel like a balloon being blown up with cold air. I loved that no one knew me as the girl whose father… anything. I was just Leila who had a knack for algorithms and an inability to pretend football made sense.

But stories don’t end just because you change the scenery. They end because something true lands and alters the orbit of everything else. This story still had circles to complete.

Ethan’s latest startup failed six months after the meeting. I know because Linda posted a Notes-app screenshot about “a difficult pivot” and “market headwinds” and “grace for visionaries” and the comments were a wreck of emojis and cousins. He took a consulting gig with a friend of a friend that involved phrases like “synergy” and “deck optimization.” Dad took a middle-management job at Uncle Marcus’s company, the same company where he used to stride into board meetings late and kissed by the satisfaction of being necessary. Now he forwarded memos and approved PTO with pained dignity. I heard this from Jeremy, not from Dad. Dad and I spoke twice—once when he called to tell me a winter storm was coming and to wear “the black coat; it’s warmer,” and once in the spring when he left a voicemail that said “I’m proud of you,” the last word breaking like a stick.

If you’re waiting for the apology scene, the dramatic dinner where he takes my hands across a white tablecloth and says the sentences any daughter in a novel wants to hear, I can’t give it to you. He sent a letter in April without a return address. It said I was stubborn like my mother and brilliant like my mother and difficult like my mother and that he was sorry he had ever made me my mother when what I wanted was my father. It didn’t say I’m sorry I took your money. But it said enough of the shape that sometimes, on good days, it almost cast that shadow.

MIT’s first year is a long hallway of rooms you enter certain and exit differently. In one, I learned to debug in the dark (metaphorically and literally when the dorm power went out). In another, I made a friend who showed me how to cook a rice dish his grandmother used to make with five ingredients and infinite patience. In the lab, I built a small thing that solved a problem for a professor who had believed problems like that were just weather. It felt like picking a lock with a hairpin and hearing it click.

On the anniversary of the will reading, the family met for dinner at Aunt Sarah’s. The lake house had gathered its new owners well; the kitchen was crowded with elbows and old arguments, the way good kitchens are. Grandpa sat at the head of the table like a man who didn’t need a throne. There was an empty chair for Grandma and no one said it, but we all looked at it when the laughter got loud. Dad wasn’t invited, and I didn’t ask why because we all knew. Linda was busy reinventing herself as a philanthropic consultant and had moved into a condo near the museum district with floor-to-ceiling windows that reflected mostly her. Ethan did not text me from the parking lot asking to be let in. He was in Bali or Boston or a co-working space inside a converted church, depending on his last post.

“Tell us about school,” Grandpa said, and I did. I tried to tell it without statistics or names, the way you tell a story to someone who wants the weather of the day, not the barometric pressure. Jeremy told me his board seat came with a colonoscopy of emails he wished he’d never read. He said he had put in motion better oversight for family trusts—the kind that would blink red before any one person could decide that “family money” means kneecapping one child for another’s hobby.

After dinner, I took my plate to the sink and found Aunt Sarah rinsing glasses in water as hot as tolerance. “I used to be jealous of you,” she said without preamble, the way truth sometimes arrives. “You got Sally for a mother and I got Ruth.” She half-smiled. “But Ruth wrote clauses that saved us all. Maybe both women saw something coming.”

“What about Dad?” I asked, bracing.

She sighed. “He’s paying back what he can. It’s not about the money. It’s about… manners.” It was such an old-world word that I laughed. She laughed, too, but there wasn’t much humor in it. “He’s learning the kind your grandmother meant—the ones that live in contracts and kitchen tables. The kind that keep you from making your children beg for what was already theirs.”

Sometime in the second year, I left the student union late and winter hit my face with the kind of slap that insists on respect. I pulled on the black coat because it was warmer and thought of Dad calling about storms. Memory isn’t a ledger where debits and credits balance by math. It’s a shoebox with mixed-up photos. You keep the ones that tell the version of the story you can live with. I kept the coat.

I interned that summer in Uncle Marcus’s audit department and discovered two things: one, people who call footnotes “blah blah” are the reason small disasters become big ones; and two, being the person who reads footnotes can feel like superhero work if you remember that saving a family is as heroic as saving a city. I wrote a report that fixed a compliance issue before it could throw a shadow over a fiscal year. He sent me a single line email: Good catch. Wanna come back next summer? I did.

Senior year, I built a capstone with two classmates that helped small nonprofits automate donor receipts and track restricted funds so nobody could pretend they forgot the rule that money given for X shouldn’t be used for Y. We released it open-source. The first download was from a family foundation in Ohio. The second was from a women’s shelter in our city. The third was from a person with an email address I knew: Ms. Patterson. My phone lit with a message from her: Your grandmother would call this a good use of a brain.

Graduation day arrived a week late because of rain. It didn’t matter. The air was the kind that loves a procession. Grandpa sat two rows back, straight as a ledger line, a scarf Grandma knit tucked into his jacket pocket like a flag. Jeremy was beside him, and my cousins, and Aunt Sarah, and Uncle Marcus. Dad wasn’t there. It was a choice that had been decided for us long before the will; the reading only wrote it down.

After the ceremony, on the lawn that tried and failed to stay neat under so many feet, Grandpa adjusted my cap and said, “Sally would be so proud.” I said, “I hope so.” He said, “I know so.” Then, because I cannot help myself, I said, “I forwarded an email. That’s all.” He put his hand on my shoulder and squeezed. “You forwarded the truth,” he said. “Sometimes the lever that moves the world is only as long as a subject line.”

Later, in the quiet between events, I opened Mom’s old locket. The photo inside was faded to the point where her smile looked like light. “We did it,” I said to the metal. The wind didn’t answer. It didn’t have to.

Ethan sent a text that week: Congrats. Let’s grab coffee, want to pick your brain for a new idea. I stared at it long enough to remember his first “learning experience,” the night he told me startups are about “burn rate tolerance” as if we were talking about s’mores. I typed: I hope you’re well. I don’t consult for free. And I don’t consult for family. He sent back a thumbs-up, then a rocket ship, then nothing.

Dad mailed a card in his cramped careful hand. It said, Proud. It also said, Sorry, underlined once, as if he’d decided while writing that the old muscles could flex. I held the card over the trash, then put it in the shoebox with the other photos. Not forgiven. Not forgotten. Just… filed.

Life after the neat punctuation of ceremonies is a sentence that goes on without a comma you can see, so you learn to breathe anyway. I moved to a walk-up with bad stairs and great light. I took a job with a firm that audited foundations because it turns out the family you choose can be a mission statement. I made friends who knew me as the person who brings extra pens and reads the fine print and laughs too loud at stupid puns. I dated a boy who fixed bikes and said “your mind is my favorite machine” and I believed him until he didn’t call for four days and the machine told me clearly to move on. I called Grandpa every Sunday. We talked about tomatoes and truth.

One autumn afternoon, a letter arrived addressed in Aunt Sarah’s neat school-teacher cursive. Inside was a photo of the lake house with new paint and an old tree and a caption: Come for the weekend. Bring that black coat. It’s colder by the water. I went. We played Scrabble. Grandpa beat us with words like “chattel” and “estoppel,” and when I groaned that this wasn’t fair, he said, “Should have paid more attention to the clauses.” I stuck Z on top of an A and said, “I did.”

Sometimes I think about that first day in the mahogany office and how small I felt and how much bigger I am now. Not taller. Just… upright. Mom’s promise wasn’t the money, not really. It was the belief that I could move through the world without borrowing permission. Dad gave my college fund to my stepbrother’s startup and called it an investment in the family. I forwarded one email and called it what it was. The email didn’t change everything. It revealed everything. The change came after, in the quiet, in the choices: in Grandpa’s clause, in Jeremy’s vote, in Aunt Sarah’s key in a new lock, in Uncle Marcus’s “Good catch,” in my “I don’t consult for family,” in Dad’s underlined sorry I didn’t cash like a check but kept like a photo.

The last time I visited Grandpa before winter, he took me to the garden and pointed to a patch of stubborn green that refused to die. “Perennials,” he said. “They don’t quit. They rest.”

“What about people?” I asked, because some questions need a witness to sound less like fear.

“Same,” he said. “If they want to be.”

On my way out, I stopped in his study. He had the email I’d forwarded printed and tucked behind a framed picture of Grandma holding a tomato bigger than her small palm. “You kept it?” I asked.

“Evidence,” he said. Then he smiled. “And a reminder.”

“Of what?”

“That promises are only as good as the people behind them,” he said. “And that pieces of paper can be shields if you hold them up at the right time.” He tapped the frame. “You held it up.”

On the drive back to the city, I passed the exit that would take me to Dad’s neighborhood. I didn’t take it. Not out of spite. Out of clarity. Some roads lead you back to rooms where you learned to be small. Some roads lead you forward. The sky ahead was the fall kind of blue—the kind that feels earned.

At a red light, my phone buzzed with a new email from Ms. Patterson: Quick question—would you be willing to advise on a pro bono project to help families audit education trusts? It won’t pay much, but it will matter. I laughed, because the universe loves a callback. I typed back: Yes. Let’s build something that makes paper honest.

At home, I taped Grandpa’s note above my desk. You forwarded the truth. Sometimes that’s the lever. Under it, I wrote my own postscript in pen: And sometimes the lever is you.

That night I dreamed of Mom at the kitchen table, paying bills with a pencil and a calculator, her lips moving, whispering numbers like prayers. When I woke, I made coffee strong enough to pass for courage and opened my laptop to work on the trust-audit tool. Sun slid across the floor like a new clause entering a contract. I thought about all the versions of family we make and unmake, about the way money is just a story with numbers in it, about how a promise made in grief is still a promise and a breach is still a breach even if you call it love.

Dad gave my college fund to my stepbrother’s startup. The email I forwarded changed everything. Not because electrons have magic, but because truth is a force and paper is a tool and love, when it is real, doesn’t ask you to pay for someone else’s fantasy with your future.

I clicked Save. Somewhere, far away, the lake breathed in its cold, and the garden remembered spring. In my small apartment filled with light and honest bills, I felt the world shift—not a lurch, not a quake. Just the almost-imperceptible movement that means a story has found its ending and a life is beginning in the open space it made.

The End.

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

My Mom Laughed: “No Wonder You’re Still Single at 31” — She Had No Idea About My Secret Wedding… CH2

My Mom Laughed: “No Wonder You’re Still Single at 31” — She Had No Idea About My Secret Wedding… …

My Mother-In-Law secretly recorded me for three months, claiming I was a terrible wife and destroying her son’s life. CH2

My Mother-In-Law secretly recorded me for three months, claiming I was a terrible wife and destroying her son’s life. …

The Silence Of My Parents Hurt Worse Than Her Words—They Let Her Crush Me. CH2

The Silence Of My Parents Hurt Worse Than Her Words—They Let Her Crush Me. Part One The room was…

She laughed in my face, claiming i was never legally married to her son. CH2

She Laughed in My Face, Claiming I Was Never Legally Married to Her Son Part One When people talk…

Why do you hate your parents? CH2

Why Do You Hate Your Parents? My parents kicked me out for getting a job and not being able to…

The Day My Parents Kicked Me Out With A Suitcase… Was The Day The Lottery Hit. By Dawn, I Was Rich. CH2

The Day My Parents Kicked Me Out With A Suitcase… Was The Day The Lottery Hit. By Dawn, I Was…

End of content

No more pages to load