Dad Called Me a Disappointment at My Graduation Party — Until I Showed Everyone the Real Reason He Never Lost His Job

Part One

“Dad, what are you doing in my room?”

I didn’t mean for it to come out as a whisper. It did anyway, small and stunned, like the voice belonged to the seventeen-year-old version of me who’d first learned what a closed door meant in this house.

He froze with his hand inside the hanging sleeve of my graduation gown. The satin fabric slithered softly against the plastic as he withdrew it, and I watched—almost clinically—as his fingers closed over a small brass shape. My spare apartment key. The one I’d sewn into an inside pocket by hand, as a favor to my always-forgetting roommate and as insurance against another “security upgrade” at home that somehow always gave my father new keys and took mine away.

A guilty flicker crossed his face. It was quick—just a tremor under the practiced mask he wore for donors and directors and country-club bartenders when he said, “Another club soda, please. Working late.”

“Your party starts in two hours,” he said lightly, palming the key, already refitting the mask. “Don’t be late.”

He brushed past me in the doorway like I was drywall, and I had the hysterical urge to laugh, because of course this was how the day would begin. Of course the man who corrected my posture on the way into kindergarten and my résumé margins on the way out of grad school would see even privacy as something to be optimized. Something to be owned.

My name is Victoria Chen. I’m twenty-two, and I just graduated from Harvard Business School with honors, a fact my father had once assured me would be—at best—a fluke.

“You’re not built for numbers, Victoria.” He’d said it when I was fifteen, slow and reasonable as a surgeon explaining prognosis. “Some people have the mind for business. Others don’t. Aim for communications. Something safe.”

Now here I was, diploma still smelling faintly of ink and pressure, and he’d celebrated the occasion by picking the lock on my life.

Rosewood Country Club glowed that afternoon like a jewelry box. Marble colonnades. Candelabras under glass. A quartet in the corner playing Vivaldi as if my childhood had never included spam fried rice, secondhand winter coats, and a mother who used coupons like rosary beads.

It was everything my father loved: attention polished to a mirror finish.

“Victoria!” he boomed from halfway across the ballroom, and hardheaded training made me straighten before I could stop myself. He hauled a man out of a knot of navy blazers and draped him in a fatherly arm. “Meet Harrison Wells from Meridian. Brilliant in sustainable capital, old friend of mine.”

I shook hands. I smiled. I congratulated Mr. Wells on his last green bond issuance and listened to him praise my thesis on pricing climate risk into logistics. Wells’s eyes were kind. He had hands that looked like they’d once hauled lumber. It was almost a relief to watch him take a step back from the blast radius that was Michael Chen.

“She tries hard,” Dad said, part wink, part warning. “Always has.”

It was a tiny sentence with a thousand razors embedded in it. The world took it as humility. I took it as the usual. Bright but not bright enough. Welcome at the table, but please don’t think you’re allowed to speak.

By sunset, the ballroom was a watercolor of expensive laughter and good lighting. The band swelled. The servers refilled champagne. My mother’s charity-circle friends smelled like bergamot and the word “tasteful.” My professors arrived on a hum of tweed and gentle pride.

I thought—naively—that Dad would make a short toast. Thank the guests. Say my name. Maybe, just for once, reach across the gulf.

He took the mic with the easy swing of a man who’d practiced into a mirror, and the room gave itself to him. Years of power had sanded his voice into something smooth and pleading-proof.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” he began, “thank you for coming to celebrate my daughter.”

Applause rolled politely across crystal.

“Victoria is—” a small pause, just long enough for me to feel the ground tilt—“adequate.”

Someone laughed too loudly. Someone else gasped. I stopped breathing.

“She works very hard. She tries her best.” He smiled into the room like a kindly emperor. “But some people are born leaders and some are born to follow. Leadership is instinct. It’s vision. It’s the ability to make the hard calls others can’t handle.”

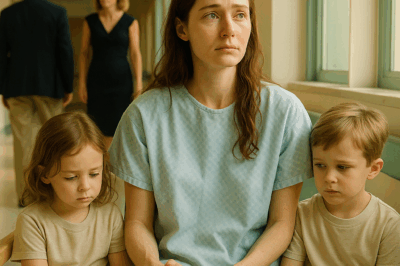

My limbs prickled. The quartet’s violins sounded like mosquitoes. I could feel three hundred eyes burning pinpricks into my dress. I could hear, absurdly, the click of my mother’s bracelet as she applauded with two fingers and the back of her other hand. Somewhere to my left, a professor muttered “good grief” and stopped it with a sip of Perrier.

“Victoria will make an excellent employee someday,” Dad concluded, his gaze sliding off me like I was glare on a screen. “For someone with real vision.”

The clapping that followed sounded like rain starting on a tin roof—uncertain, then embarrassed, then dying out.

I smiled. I nodded. I shook hands that felt suddenly surgical, as if everyone were afraid to touch the wound. A man I’d never met told me I was brave. A woman from Dad’s board squeezed my elbow with a intensity that felt like apology. When I slipped away to the bathroom, my calves were vibrating.

The face in the mirror was not the face that had walked across the stage three months ago. That girl’s spine was made of scaffolding. This one’s spine was made of glass. She looked like she’d been told a story she’d believed her whole life, only to find out it had always ended this way.

“You’re not built for numbers.”

“What’s ‘vision’ without control dressed as concern?”

“Try harder.”

Maybe the thing about humiliation is that it strips more than skin. It strips denial.

I stared at the girl in the mirror and thought of the key in my father’s fist that morning. I thought about locks. About doors. About who held the right to open what.

An hour later, under the lacquer of photographs and flutes and borrowed conversations, I slipped out. I didn’t go back to my apartment. I drove to Beacon Hill.

The house looked the way it always had at night, a careful Victorian in decent shoes. I let myself in with a key I’d made in a strip mall when I was seventeen. My mother was at book club. My father, presumably, was seducing a venture capitalist with a story about grit.

His office door yielded to the brass key hidden inside the back of a drawer in my old room.

Leather. Wood. Bragging framed in glass. The office smelled like a rich man’s yachting cologne. I started with the desk. Paperwork as décor. Contracts like paperweights. It felt, at first, like snooping through a thrift store.

The bottom right drawer was locked.

The small velvet pouch under the loose board behind the desk felt like a magician’s justification—of course it would be here. The key fit like a sigh. The drawer groaned open.

A manila folder. Black ink.

PERSONAL INSURANCE.

Inside: photographs that looked like grainy stakes driven into someone’s heart. Parking lots. Envelopes. Hands that weren’t my father’s taking envelopes from hands that were.

Bank statements. Wire transfers. Names you didn’t forget if you followed finance news. USB drives labeled with dead companies’ names like gravestones.

A small digital recorder. A sticky note in my father’s handwriting that said MORRISON — FINAL DAY.

I pressed play.

My father’s voice—miniature and terrible—filled the room. “The Henderson acquisition files are on my desk, third drawer down, behind the Peterson contracts. You’ll want the environmental reports, especially the groundwater contamination studies they buried.”

Another man’s suspicion. “You’re sure Chen doesn’t know you’ve got this?”

“My boss thinks I’m too loyal to notice his little coverups,” my father replied, and I heard him smile. “Amazing what people don’t see when they trust you.”

I stopped the recording and braced both hands against the desk to stop the room from turning.

Morrison & Associates hadn’t died of budget cuts. It had died of hemorrhage. Preston Holdings had collapsed under scandal. Whitman Group under handcuffs. And every time, Michael Chen had landed, catlike, somewhere higher, cleaner, richer. He’d never been laid off. He’d shed skin and slithered.

I flipped open the leather notebook. His handwriting slanted like a man leaning into a wind only he could feel. “Target: vulnerable CFO at Preston (J.T.). Drinks too much. Likes flattery.” “Cultivate: competitor analyst (Blake S.). Willing to pay for ‘market insight.’” “Deliverables: M&A documents, board minutes, environmental reports.” “Insurance: copies locked, Beacon Hill office. Never email.”

The last page punched the breath out of me. Red ink in a ring around two words:

CHEN INDUSTRIES.

It was like watching a man light a match at his own gas pump.

The front door opened and shut downstairs.

“Victoria?” His voice rolled up the stairwell like a bowling ball. “Your car is in the driveway. Where are you?”

I closed the folder, slid the drawer, pocketed the key, and faced the door as he filled the frame.

We stared at each other across thirty years and six feet of polished wood.

“Hi, Dad,” I said gently. “We need to talk.”

“What are you doing in my office?” He worked so hard to keep his voice level that the tremor sang under it. That was the thing about men like my father: they thought control was quiet until the quiet broke.

“What were you doing in my bedroom this morning?” I leaned back against his desk and crossed my ankles. “I suppose we both have boundary issues.”

“This is my house,” he said, stepping into that easy stance of his, hands clasped behind him like he was the dean of something. “Those are my papers.”

“Like your ‘personal insurance’?” I asked, and watched his face bleed of color.

“You don’t understand what you’re looking at.”

“Oh, I think I do.” I slid my phone out of my pocket and held up a photo. Grainy parking lot. Envelope changing hands. “I understand that you never got ‘laid off.’ I understand that every company you’ve worked for is a crater. I understand that you didn’t build an empire—you burned one, piece by piece, and moved into the house next door.”

He sagged into the chair I had just vacated. The sight made something childish and mean in me want to cheer. I didn’t.

“The business world is complicated,” he said finally. “Sometimes you have to make difficult choices.”

“Is that what you call selling inside information? ‘Difficult choices’?” I smiled without humor. “Does your therapist know you rebrand felonies like they’re lean management initiatives?”

“I provided for this family,” he snapped. “Everything you have—your schooling, this house—came from my success. I did what had to be done.”

“Successful arson is still arson.”

We sat with the wreckage between us. It hummed. The office seemed smaller now, like a boat taking on water.

“There’s someone else who knows,” I said softly. “Sarah Martinez. Securities investigator. Her father worked at Morrison.” He stared. “She’s been building a case for two years. She was at the party tonight.” I let the word hang like a fish on a line. “She saw your little speech.”

“Why would you—” He stopped. “You told her?”

“I didn’t have to. She’s been waiting for someone in your orbit to cut the lights.”

“What do you want?” he asked, and there was the smallest sound in it—fear, or the shadow of it.

“To make sure that speech was the last time you ever call me a disappointment and get away with it,” I said. “And to give you one gift you’ve never given anyone: fairness.”

The next morning, I met Sarah at a Cambridge coffee shop that did its espresso like penance. She was younger than I expected, crisp blazer over sneakers, eyes like a blade and hands that looked like they’d pot a plant with precision.

“I wondered when you’d reach out,” she said, opening a laptop. “Cousin of mine catered last night. Texted me a live-blog. Your dad enjoys public cruelty.”

I slid the photos across. She scrolled. Her face changed. “This is… everything,” she breathed. “Dates, transfers, names, deliverables. Jesus, Victoria. With this we don’t just tug a thread. We pull the whole sweater.”

“What happens to him?”

She didn’t flinch. “If he’s charged on what I think we can prove? Wire fraud, insider trading, conspiracy. Maybe RICO if we can map the network. Ten to twenty.”

“Ten to twenty,” I repeated. The number felt like a room I could open.

She closed the laptop and looked at me. “I know this is your father.”

“No,” I said. The word was simple and true. “A father protects his children. He didn’t just fail to protect me. He trained me to be small enough to fit under his shoe.”

She nodded once. She’d heard it before, worded different but the same.

“We move at your signal,” she said. “But if you’re willing, we’ll make the signal loud. He scheduled a press conference this weekend at Rosewood, didn’t he? Announcing the Chen-Coastal acquisition?”

“He did.”

“Good.” A smile that wasn’t pretty cut across her face. “Bring your laptop. Bring an HDMI cable. And practice the tone you use when you’re done being polite.”

The strange thing about clarity is how it calms. The days that followed had a quiet to them that felt like placing heavy china into boxes exactly the right size. I worked. I ate. I slept. I called my mother and listened to her talk about hors d’oeuvres as if those were the only orders of the day. I watched my father’s face on fractioned local news proclaiming that Chen Industries stood for integrity.

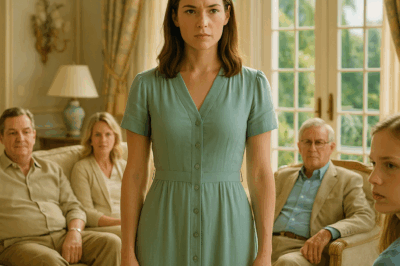

On Friday, I stood in my old room and slid the brass key into my pocket like talisman and threat. On Saturday, I wore a navy dress that made me feel like a paperweight—you could throw weather at me and I would not move. The ballroom at Rosewood glittered.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” my father began, restorative as a gin and tonic, “thank you for joining us as Chen Industries looks ahead to—”

“Excuse me,” I said, and took the second microphone.

Three hundred heads swiveled.

I didn’t shake.

“Before we look ahead,” I said pleasantly, “let’s look behind.”

I plugged my laptop into the projector with the HDMI cable I had polished with my sleeve. The ballroom’s twenty-foot screen flickered, then showed—magnified and unavoidable—a photograph of my father’s leather notebook. The red ink circle around CHEN INDUSTRIES looked like a bruise.

My father’s smile calcified.

In the fourth row, near the aisle, Sarah Martinez’s posture changed by a degree that meant now.

“Twenty years ago,” I said, “my father explained layoffs to me as bad luck. He had a lot of bad luck. He left a lot of companies at exactly the right moment.” I clicked.

A timeline appeared, names in white text against black. MORRISON — 2008 (collapse after environmental lawsuits). PRESTON — 2010 (insider trading). WHITMAN — 2013 (CEO arrest). Each line wore a date and a headline. Between them, small gray arrows carried wire transfer records with dates that matched leaving parties.

“We tell good stories about men who always land on their feet,” I said. “We don’t discuss who broke the staircase for them to hit the ground without bruising.”

A low, collective sound moved through the room. The kind you hear at funerals when someone finally names what everyone else smelled.

“Victoria—” My father’s voice shredded into the mic.

I didn’t turn. “Would you like to narrate this next part, Dad?” I asked. “It might save my voice.”

I pressed play.

From the sound system, his voice arrived: “The Henderson acquisition files are on my desk… You’ll want the environmental reports they buried…”

Someone swore under their breath. Someone stood, then sat again like they’d remembered where they were. Mr. Wells from Meridian went pale. I watched in my peripheral vision as Robert Huang—the most loyal of my father’s partners—took a slow, deliberate step backward until his calves hit a chair and he sat down like the idea had belonged to him.

Security began to move. So did the men in suits who weren’t security.

“Chen, that’s enough,” a board member barked. “Turn it off.”

“We’ll get to questions,” I said. “I’ve learned a lot about Q&A from watching a man explain why his daughter is ‘adequate’ in front of three hundred of his closest friends.”

Soft laughter broke loose from somewhere crowded with women. It was not laughter against me. It was for the first time in a long thing like oxygen released.

“Here are the bank records,” I continued. Transfer numbers marched across the screen in tidy rows. “Here are the shell companies your attorneys will pretend you don’t recognize. Here are the USB drives—yes, physical—because our protagonist prefers portable deniability. And here—” I clicked to the final slide, the one that had changed the temperature of the room when I first took it, “—is his list of targets.”

The red circle looked devastatingly personal forty feet across.

“Mr. Chen,” someone said, and I heard the federal government in it, “step away from the podium.”

He didn’t move. My mother, for once in her life, did. She stood—thin at the throat, lipstick perfect—and put a hand on his sleeve.

“Michael,” she said softly, like the beginning of forgiveness, “don’t.”

He wrenched his arm away. “Who are you,” he snarled into the mic, “to do this to your family?”

A murmur that could have been shame went through the crowd. It might have been mine if I had still been the girl who trimmed herself to fit his narrative. I wasn’t.

“A father protects his family,” I said. “You used yours as camouflage.”

The rest happened very quickly and very slowly. Hands on his elbows. Words about warrants and counsel. Sarah’s small nod across the room as if to say nice pacing. The room split along invisible lines—shock, denial, calculation, relief. In the back left, someone started clapping. It sounded like rain beginning far away and was, mercifully, not about me.

When they took my father away, he didn’t look for me. He looked for Mr. Wells. For the board. For anyone with equity in the version of himself he preferred. The door shut. People started breathing again.

I stepped back from the microphone. In the third row, my mother was still standing, her hand slowly pulling at the edge of a napkin like a loose thread could fix what had never been knit.

“Mrs. Chen,” I said, my voice gentle now because after fury comes mercy or it curdles, “you might want to sit.”

She did. A sound that might, someday, be a sob left her.

I unplugged the HDMI. The screen went dark. The quartet stared at their instruments as if wondering if music was appropriate.

“Victoria,” Mr. Wells said, rising, his voice rough. “I think I owe you an apology.”

“For laughing?”

“For believing a story I should have interrogated,” he said. “And for not being as brave as you.”

“I’m not brave,” I said. “I’m done.”

He nodded like bravery and done-ness were cousins. “If you ever want to build compliance the right way,” he said, voice lowering, “call me. We need people who know the difference.”

Sarah found me near the bar where the canapés were dying a quiet death. She held out a hand and then, without asking, pulled me into a hug. She smelled like coffee and printers and sleep debt.

“You did it,” she said into my hair.

“No,” I said. “He did.”

“Fair,” she conceded, releasing me. “But you put a microphone to it. That matters.”

Part Two

News moves faster than shame, but not by much. By Monday morning, the words Chen and indicted were getting along in headlines. Jong Systems cancelled lunch. Meridian postponed a roadshow. The board moved from statements to “with immediate effect” memos.

I slept. I ate the first real breakfast I’d tasted since high school. I answered exactly two calls—my mother’s (not ready) and Sarah’s (ready enough).

On Wednesday, I stood in a federal conference room so beige it felt like punishment and signed my name to six separate agreements. Cooperation. Disclosure. Non-retaliation. Each pen stroke felt like stitching up a wound I’d spent years pretending wasn’t bleeding. A woman across the table with a bun tight enough to pull opinions into her scalp looked at me over steepled fingers.

“You understand,” she said, as if I might not, “this will likely put your father away for a long time.”

“I understand,” I said. I did. What I also understood—and did not say—is that “a long time” had already passed while he was free.

My mother sent six letters in the first month and then none. The last one was small and terrible and honest.

I watched you walk into a room where men like your father own the oxygen and you didn’t suffocate. I’m sorry I taught you to be quiet. I thought it was safety.

I put the letter in a drawer with the spare brass key. Objects are strange things. They clutch meaning long after utility. I kept both as reminders: there had always been ways out. I had finally used one.

Work happened in the way of rebuilding after deliberate burn. Chen Industries’ board hired an interim CEO who looked like she could cold-stare marble into confession. She asked me to come talk to their audit committee. I said yes, with a stipulation: if I came, I came with a plan and with authority. If I came, there would be no more “adequate.”

The plan took shape like a structure you realize had been waiting under your skin the whole time. Internal audit that actually reported to the board. Whistleblower channels that didn’t route through HR like a rumor mill. Vendor vetting that looked at the person and the LLC the person hid behind. No more “trust as a control.” Trust only as a goal.

“Who are you?” one director asked me in mild disbelief after my third slide about one-way hash functions for digital signature verification. He meant, I think, the girl his friend had publicly gutted at a party. He meant, Isn’t this too much? He meant, Are you done yet?

“I’m the person who makes sure you never again mistake noise for value,” I said. “Or loyalty for silence.”

They gave me the title Chief Ethics & Risk Officer. The letters didn’t thrill me. The budget did. With it, I hired a small team of people who spoke policy like poetry and code like music. We built tools to catch shadows before they grew teeth. We rewrote the rule that had almost eaten me: If something looks off, it is. You don’t need permission to say so.

My old calculus teacher sent a card that said, I always knew numbers would be yours. I just didn’t know which ones.

On a Tuesday in May, I walked into a classroom at my old high school and told a room of girls in black leggings and high buns what I wished someone had told me. That being good at your job won’t protect you if you work for someone determined to shrink you. That you are not sensitive; you are accurate. That if your father shows you who he is, believe him the first time. That there are keys you can make yourself.

Afterward, a small girl with braces and eyes like a forest after rain asked, “What if they call you a disappointment?”

“You say, ‘To whom?’” I said, and watched it slide into her pocket like a stone she’d keep for skipping.

The trial started on a wet morning and stretched for weeks. It had all the wrong kind of drama: charts and hushed instructions and the jury looking tired before it even began. The press enjoyed the arc—self-made man undone by daughter’s “revenge.” They missed the plot. It wasn’t revenge. It was repair.

I took the stand with my spine made of paperweight again and answered questions like I was teaching a class no one wanted to take but everyone needed to pass. I said “Yes, that is my father’s voice.” I said “No, I did not doctor those records.” I said “I took photographs because paper burns.” I looked at no one at the defense table. It felt like keeping an old wound from fresh contamination.

When the verdict came—guilty on wire fraud, guilty on conspiracy, guilty on securities fraud—the room did not exhale. It reset. The kind of silence that follows a storm not because it is over but because the air has been rinsed clean.

He didn’t look at me. He looked at the door. It would not open for him.

At home, I poured tea into a cup with a hairline crack and took the smallest pleasure in how it did not leak. The headlines moved on. Companies stop bleeding slowly. They also heal slowly. We hired a director of people who understood the word care without needing to italicize it. Anonymous tips started arriving like paper airplanes from rooms I’d never been in. We answered them all.

On a quiet Saturday, my mother came to my apartment and stood in the hallway with a Tupperware like a pilgrim.

“Lemongrass chicken,” she said without preface. “Yours is too dry.”

“Not with enough coconut milk,” I said automatically, and stepped back to let her in.

We didn’t talk about the trial. We talked about how to keep basil alive. We talked about the cashier at the store who calls everyone hon and the best dumplings on Kneeland. She washed my teacups and criticized my drying technique. When she left, she put her hand on my cheek like she was discovering I was warm.

“I was scared,” she said. “Not of the law. Of… life without the man I thought I married. I thought keeping you small would keep us safe.”

“All it kept,” I said gently, “was me small.”

She nodded once. The door didn’t close a second time. It didn’t need to. We were learning a hinge.

A year later, Sarah and I spoke at a conference for women in finance in a ballroom not unlike the one where my father had tried to teach me my place. We came armed with slides and seven jokes we promised not to use. We told a room full of suits with earrings how to see the difference between charisma and character. How to build systems that caught rot before it bloomed. How to listen to the person who says, “Something isn’t right,” even when it ruins your lunch.

A woman in the front row cried during Q&A. She said she didn’t know why. We did.

After we stepped off the stage, Mr. Wells from Meridian found me.

“You delivered,” he said simply.

“So did you,” I said, because when the scandal hit, he had signed the letter to the board demanding transparency instead of waiting it out with a lawyer in his pocket.

We shook hands like people who had carried glass together without breaking it.

The last time I visited my father, he was in a room that smelled like mop water and coins. The fluorescent light did him no favors. He still had hair like a brochure and eyes that tried to pretend they’d never seen me.

“Hello, Victoria,” he said.

“Hello, Michael,” I replied.

He didn’t ask for forgiveness. He asked for news. I gave it to him like you hand a stranger directions—clean, unemotional, points of interest omitted. He tried to weave a story about sacrifice. I stood up, and the chair legs scraped something sharp out of the floor.

“You turned your daughter into a prop and your company into a weapon,” I said. “That is not sacrifice. It is hunger. You mistook other people’s hope for a feast.”

As I left, he called, “I did build something.”

“You did,” I said without turning around. “Me. But not the way you think.”

Outside, I breathed air that didn’t know his name. I bought a pastry I didn’t need and a new plant I had no guarantee I could keep alive. On the walk home, it started to rain the way Boston rains in good months—like permission. I tilted my face up and thought about doors. About keys. About the girl who’d watched a man take hers out of a gown sleeve and thought that meant the story was his.

The next morning, I put on a navy dress and went to a board meeting to argue against a shortcut someone called “pragmatic.” I told them why pragmatic looks so much like rot at the beginning. I used the word adequate once, carefully, as a joke, and watched it land like an old ghost exorcised.

After work, I stopped by my mother’s. The house smelled like lemongrass chicken and apology. She pressed leftovers into my hands and kissed my forehead as if she had always done that. Maybe in some parallel lifetime, she had. We were making do with this one.

At home, I slid the brass key onto a ribbon and tied it inside the spine of a notebook where it would not rattle. I wrote on the first page: Some doors are locked for a reason. Some are locked out of habit. Learn the difference.

Then I went out to the fire escape with tea and watched lights come on in windows across the city as if people were taking turns saying, “I’m here.” I sat until the cup went cold. I went to bed with the window cracked like the world might speak if I let it.

I slept.

I dreamed I was standing in a ballroom where the chandeliers were quiet and the microphones were off, and I was not a disappointment and I was not a daughter and I was not a committee. I was a person with a hand on a cord and a choice about what to plug into the wall.

When morning came, I made rice like my grandmother used to—just enough water, patience, and a low flame. I ate with chopsticks in silence that felt earned. Then I put on my paperweight spine and went back to a place where men still thought suits were magic. I built something anyway.

Here is the thing I learned the day I gave the most important presentation of my life: sometimes the truth is not loud. Sometimes it is a steady projection on a wall taller than your childhood fear, and you stand beside it and say, softly, “Look.”

And sometimes that is enough to end one story and begin another.

END!

News

Parents refused to care for my twins during my surgery, called me a “burden”, and went to a concert. CH2

Parents Refused to Care for My Twins During My Surgery, Called Me a “Burden,” and Went to a Concert …

I gave my daughter a villa, but her husband’s family moved in—one line made them pack and leave. CH2

I Gave My Daughter a Villa, But Her Husband’s Family Moved In—One Line Made Them Pack and Leave Part…

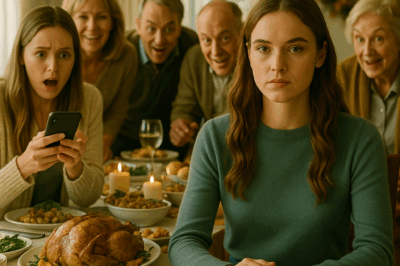

On thanksgiving, my sister found out i had $18 million and my Family wanted….they had to regret it. CH2

On Thanksgiving, My Sister Found Out I Had $18 Million—And My Family Wanted… They Had To Regret It Part…

At my sister’s wedding, she and my mother mocked me, calling me a single mother and a used product… CH2

My sister’s wedding, she and my mother mocked me—calling me a single mother and a “used product.” They didn’t know…

BREAKING: Elon Musk Donates $1 Million to Fund Nearly 300 Murals Honoring Iryna Zarutska Across America — Move That Moves the Nation!

BREAKING: Elon Musk Donates $1 Million to Fund Nearly 300 Murals Honoring Iryna Zarutska Across America — Move That Moves…

My husband left with his girlfriend, leaving me with $75,000 in debt. Then, my 12-year-old son said. CH2

My husband left with his girlfriend, leaving me with $75,000 in debt. Then, my 12-year-old son said… Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load