You’re Being Selfish! Said My Son And His Wife Threw Wine At Me, So I Texted My Lawyer!

Part 1

I never pictured Easter ending with a wine-soaked shirt, a cut blooming above my eyebrow, and the cold hum of a hospital waiting room. Yet there I sat, typing four words to my lawyer: Phase 1 is complete.

My name is Robert Chen. I’m sixty-three, retired three years from an accounting practice I built with stubbornness and spreadsheets. My wife, Sarah, died five years ago. Grief hollowed the house at first; then the quiet learned my name. We bought this three-bedroom in North Vancouver in ’92 for $170,000. Today, the same clapboard and lilac hedge are worth nearly two million. The neighborhood traded station wagons for EV chargers and toddlers named for constellations.

My son, Daniel—thirty-two, pharmaceutical sales—arrives with a new suit every quarter and metrics in his mouth. His wife, Britney, travels with perfume that reaches rooms before she does. Two children: Emma, eight, all elbows and imagination; Lucas, six, who believes chocolate eggs are proof that magic repeats.

They came at three. Easter brightness through the front windows, the leg of lamb resting on the counter, rosemary and garlic laying a memory over the afternoon. Daniel hugged me like we had an audience. Britney placed a bottle on the counter like a calling card. “From the Okanagan,” she said, smile calibrated. “Exceptional.”

The kids were themselves—blessedly unperformed. They showed me eggs and tiny prizes, their voices tumbling. I showed them the hot cross buns. “Grandma’s recipe,” I said. Emma’s face softened like she remembered the smell.

We sat. The good china waited in the dining room, but Daniel wanted to “chat first.” Daniel never wants to chat first.

“Dad,” he began, glancing at Britney, “we’ve been thinking about your situation.”

“Living alone,” Britney put in, perched like a bird on a wire, greedy for balance, hungry for flight. “Big house. Falls happen. What if no one’s here?”

“I have neighbors,” I said. “A phone. My legs still do their job.”

“We have a proposal,” Daniel said, voice measured, eyes fixed to hers like they were reading a teleprompter only they could see. “Britney’s parents just retired. Sold their place in Kamloops. Market’s insane. They’re looking in the Lower Mainland.”

“Why not here?” Britney smiled, sugar on glass. “You have two spare bedrooms. They’d pay rent. Mom’s a former nurse. Dad’s handy. Built-in help. Family.”

“You want your parents to move into my house,” I said.

“Win-win,” Daniel said. “Practical.”

The lamb timer saved me from the first explosion. I nodded, left for the kitchen, shut my eyes five seconds, and felt the plan that my lawyer, Richard Thompson, and I had set months ago tighten like a knot catching. We had laid safeguards quietly: a cognitive assessment (passed, stamped, dated), a new will with a no-contest clause, a living trust with instructions that read like a map, and—Richard’s idea—discreet cameras in the living room, the dining room, the kitchen. “If they try something,” he’d said, stirring a Tim Hortons coffee, “we document. You stay calm. Let them draw their own picture.”

Dinner sang. The kids were wonder. Then Daniel circled back to the pitch.

“I’ve thought about it,” I said finally, setting my fork down. “I’m not taking roommates. I like my routine. If I need help, I’ll hire it.”

“Roommates?” Britney’s voice sharpened. “They’re family.”

“I’ve met them twice,” I said.

Daniel leaned forward. “Be reasonable. You’re sixty-three. At seventy, seventy-five—”

“On my terms,” I said. “If, when.”

“Those places cost a fortune,” Britney snapped. “Why pay strangers when family—”

“Because this is my money,” I said, “and my house.”

Air left the room like a curtain ripped down. I sent the kids to the living room. Emma looked back once; I nodded and tried to look like safety.

“You’re unbelievable,” Daniel muttered. “Selfish.”

“That’s a boundary,” I said.

Britney rose. “Do you know our mortgage? Childcare? We’re drowning while you squat on two million dollars of empty bedrooms.”

“I live here,” I said.

“Alone,” she shot. “Sarah’s been gone five years. When do you stop hoarding grief and think of someone else?”

It hurt. I didn’t show it. “I said no,” I said.

“Why?” She leaned in, all teeth and wine.

“Because I don’t want to,” I said.

She grabbed her glass and flung it. Wine splashed my face, my shirt, the wall. The glass struck the table edge, shattered. A shard kissed my eyebrow. Warmth. Then red. Daniel barked her name, uselessly.

“I’m going to the hospital,” I said, voice level as the exam table I knew I’d find. “Please leave my house.”

In the bathroom mirror, I looked like a bad joke: blood and Cabernet. In the driveway, the evening brightened like nothing had happened. At the first red light: Phase 1 is complete.

Part 2

The ER triage nurse was brisk kindness. Thompson arrived before the doctor. Fiftyish, grey at the temples, brown leather shoes that never scuffed, eyes that missed nothing. He listened, typed, nodded. “And the cameras?” he asked.

“They saw everything,” I said.

“Good.” He breathed out, a man seeing a blueprint match a building. “Do you want to press charges?”

We had rehearsed this question until it stopped tasting like betrayal. “Yes,” I said. “Assault.”

The RCMP photographed the cut, bagged my shirt, and took my statement. “Assault with a weapon,” the sergeant said neutrally. “Given your age, we’ll note the elder abuse context.”

“Elder,” I repeated. The word felt clinical and accurate both.

The doctor glued me back together. Thompson drove me home. We watched the footage: the pitch, the pressure, the insult, the wine, the shard, my leaving. “You look reasonable,” Thompson said, not as flattery, as strategy. “She looks reckless.”

“What happens now?”

“Britney gets charged. You request a peace bond. Tomorrow we file the financial exploitation complaint about the account access.”

Three months earlier, my advisor had called: attempted login on my investment portal, security answers guessed, IP traced to Langley—to Daniel’s address. I hadn’t confronted him then; I had called Thompson. “I see this weekly,” Thompson had said. “Impatience pretending to be concern. We set traps that catch behavior, not people.”

I turned off my phone that night because Daniel kept calling and guilt is louder at 11 p.m. The next morning, the RCMP filed charges. The next day, the bank froze my accounts, then thawed them after we proved I’d been at a dentist appointment during the attempt. The day after, I sat in front of a judge. A restraining order for Britney. Conditions for Daniel: forty-eight hours’ notice, daylight hours only.

On Friday, Daniel came anyway. Alone. Unshaven. Eyes bruised by bad sleep. I opened the door and stood in the frame.

“Dad, please. She’s sorry. She was stressed.”

“She meant it when she threw it,” I said. “And you let it happen.”

“I tried to stop her,” he said to his shoes.

“Not hard enough.” I held up the cognitive assessment: perfect scores, recent date. “Don’t say decline to me again.”

He blinked. “We were worried.”

“You were building a case,” I said. “Move your in-laws in. Establish ‘need.’ Push for power of attorney. It’s a tired play. I’ve seen it. I’ve balanced ledgers for families pulled apart by quieter versions of this.”

“We wanted to help.”

“You tried to access my accounts. You called me selfish in my kitchen. You planned your in-laws’ arrival like a siege.” I let the silence land. “I’ve updated my will. You’re still in it—if you respect the guardrails. Contest it, claim incompetence, manipulate finances—you get nothing. Emma and Lucas have education trusts outside your reach. They’ll be fine.”

“You’d cut me off?”

“You threw me away first,” I said, “for two empty bedrooms.”

He swallowed, something like a man discovering the cost of a belief. “Britney’s parents lost their deposit because of this. We were counting on living here.”

There it was—the pronoun cracking open the lie.

“Leave,” I said. “Next time, forty-eight hours’ notice through Thompson. Or I call the police.”

He stood in the yard three minutes, then left.

Six months unspooled. Britney pled guilty: conditional discharge, two years’ probation, anger management. The elder-abuse note sat in the file like a warning light. The RCMP declined to prosecute Daniel’s attempted access; family complicates charges. The bank hardened my fortress. Daniel wrote letters—apologies braided with budgets, childcare invoices, a job performance dip, a promise that they’d meant care, not conquest. I kept the letters. I didn’t answer.

I booked Scotland. Sarah and I had circled it on maps we never reached before chemo turned calendars to ash. I bought a carry-on stubborn enough to refuse the baggage carousel. I let the house be quiet on purpose.

Emma’s drawing arrived in the mail—three stick figures at a park, hearts hovering, I miss you, Grandpa in crayon. I cried the way grief teaches: silently, with shoulders. I didn’t call Daniel. I will wait. When she’s eighteen, she can choose coffee and questions. I will answer them plainly.

Part 3

Boundaries are boring and that is their power. I learned to love the unremarkable: the kettle’s private thunder, the smell of rain on hot concrete, a book club where nobody brags and everyone brings snacks, watercolor classes where my trees lean the wrong way and my teacher calls it wind. I met Patricia, a widow with a laugh that makes rooms remember they’re not lonely. We walk most Thursdays, two people who have learned how not to compete with silence.

Thompson and I finished the paperwork architecture. The living trust names an independent trustee. The house—this sturdy vessel through summers and influenza and Sarah’s last spring—sits snug inside the trust with clear instructions: I stay as long as I choose; if I choose to sell, I choose where to move; if I die, the trust handles taxes first, then distributes according to a table clean enough for any auditor to smile.

Britney’s parents sent a letter once—handwritten, contrite, unpunctuated apology. They said they hadn’t known the plan included “insisting,” that they were “just told it was settled.” I believed them in the way you believe a forecast after you’ve already looked out the window. I wished them well from the desk where Sarah used to make Christmas lists. I did not invite them to tea.

Sometimes in the evenings, I turn on the living room camera and watch recordings—not of Easter, never that—but of the ordinary days since: me watering the ficus, Lucas racing a toy car on the rug on a supervised afternoon visit arranged by Thompson’s office, Emma curled in an armchair reading, Patricia sipping tea and telling me about a cedar waxwing on her fence. It’s a strange comfort: proof that I live the life I chose, not merely the life I defended.

The neighborhood kept changing, as neighborhoods do. A new family moved in across the street with a toddler who tried to carry three dandelions in one hand and cried when two fell. I taught the kid the trick: one stem between each finger. He looked up at me like I’d invented generosity.

I bought furniture sliders because the couch needed to be six inches to the left. I replaced the smoke detectors. I cleaned gutters, then hired someone because ladders are arguments I no longer need to win. I installed grab bars in the bathroom—not because I’m frail, but because prudence is a friend. I got my flu shot with the ocean beyond the clinic smelling like clean cold.

On a walk, I passed a shop window with a suit that looked like the one I’d married in: navy, honest, a little formal. I stood there longer than a man should and let the wanting be affection, not ache. I went home and made Sarah’s buns with too much orange peel and ate one over the sink like an undergraduate.

Part 4

Easter lives in the same calendar square every year. The house remembered. I set the table for one, then two when Patricia texted that lamb sounded good if I had leftovers. The lilies opened on the counter with a smell so clean it felt like beginning. I poured exactly one glass of wine and drank it slowly, the way caution taught me.

At dusk, I sat on the back steps with the garden tilted toward evening. I thought about the first time Daniel called me selfish. I thought about Britney’s wrist flick, a gesture that looked like a habit. I thought about power—the kind people seize and the kind people reclaim. Then I stood and watered the hydrangeas because they were thirsty and that mattered most in that minute.

The last letter from Daniel came on a Tuesday, a crisp apology that tried on humility and almost fit. He wrote about therapy, about anger he didn’t know how to name, about fear that wore practicality like a costume. He wrote that he missed me. He wrote that Emma asked questions. He wrote please.

I called Thompson. We drafted a reply together that used the words possible and supervised and stepwise and accountability. We arranged a series of brief, daytime visits in my living room with a third party present. The first one happened on a bright Saturday. Daniel stood in the doorway like a boy and a man both. We spoke mostly about hockey. We spoke not at all about Easter. It was awkward. It was progress. When he left, he stood on the porch a moment and said, “Thank you.” I said, “You’re welcome.” Sandra—the neighbor who pretends not to eavesdrop—pretended not to eavesdrop. The street went on being itself.

After he left, I sat at the table and wrote a short note to myself on the back of a grocery receipt: Boundaries are bridges when both sides decide to meet. I tucked it under the salt shaker, a tiny motto disguised as clutter.

Scotland is on my calendar now—Edinburgh, Skye, the Highlands. I’ve circled a train route like a child with a crayon. Patricia says she might join for the last week if her sister can watch the cat. I said I’d save her a seat on the ferry. She laughed and said I was getting ahead of myself. I said that’s the point.

If you’re reading this because your child called you selfish, because a wine glass flew, because someone you love used the word decline like a crowbar, listen to me: write things down. See a lawyer who knows where these roads lead. Let cameras catch behavior. Don’t buy peace with your safety. Make your will a fortress and your heart a house with doors you open by choice.

Family isn’t a deed. It’s a daily contract: respect, autonomy, care that doesn’t require conquest. The night I texted Thompson from the hospital, I wasn’t just pressing charges; I was choosing how the rest of my years would sound when I woke—quiet, yes, but not lonely; soft, yes, but not weak; mine.

I sleep well. The doors are locked. The cameras blink like patient fireflies. In the morning, light moves across the living room floor in long rectangles, and I stand, put the kettle on, and thank whoever’s listening that I am still here, exactly where I decided to be.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. I adopted my nephew after my sister died. Christmas came. My mother-in-law said, “Only real…

I adopted my nephew after my sister died. Christmas came. My mother-in-law said, “Only real grandchildren at dinner. Don’t bring…

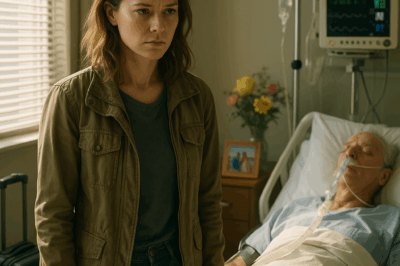

CH2. I CAME HOME AFTER YEARS AWAY – AND FOUND DAD IN A HOSPITAL, ON LIFE SUPPORT. MOM AND MY SIBLINGS…

I came home after years away – and found Dad in a hospital, on life support. Mom and my siblings?…

CH2. Her boss secretly erased her raise — But she built the system that exposed every lie

Her boss secretly erased her raise — But she built the system that exposed every lie Part 1 The…

CH2. My brother jeered my inheritance, saying he’d get the house and dad’s business; until the lawyer…

My brother jeered my inheritance, saying he’d get the house and dad’s business; until the lawyer… Part I —…

CH2. The Irony: ‘Leave!’ They Said, Unaware of My Ownership. The Moment I Revealed the Truth.

The Irony: ‘Leave!’ They Said, Unaware of My Ownership. The Moment I Revealed the Truth. Part 1 “I don’t…

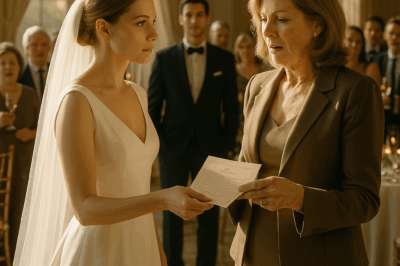

CH2. At My Wedding, Mom Smirked: “It’s Just a Car.” So I Handed Her the Legal Envelope…

At My Wedding, Mom Smirked: “It’s Just a Car.” So I Handed Her the Legal Envelope… Part I —…

End of content

No more pages to load