“You need to move out,” my parents said on Christmas. “Really?” I replied. The next morning, I packed & left … Now they’re stuck in a lie.

Part I — The Christmas Sentence

It was the kind of Christmas Eve that always smelled like cinnamon and old arguments. My mother had her wine glass in one hand and the remote in the other, flipping between a televised yule log and a rerun of a sitcom about a family that loved each other the way furniture fits a room. My father sat in his chair like a permanent fixture, wrapped in a cardigan that cut him off from consequence.

He didn’t look at me when he said it.

“You need to move out.”

No windup. No speech. The sentence landed in the living room with the soft authority of something rehearsed.

My mother nodded, eyes never leaving the flickering screen. “It’s time, Nathan.”

I smiled before my face knew why. “Really?”

“Don’t make a scene,” she said, as if I’d stood to flip the tree. “We’ll settle up. Daniel’s helping now.”

Daniel. The golden son. The charmer. The one who could sell frost to a January sky. He wasn’t there that night—he never showed for the quiet parts. But his name sat in the room like a third parent.

“I’ll go after breakfast,” I said, calmly enough to fool us all. “Merry Christmas.”

In the kitchen, the pie steamed. In the hall, the wreath shed polite crumbs of pine. In my head, something clicked into place with the precision of a lock receiving the right key.

I didn’t sleep. I lay in my childhood bed, the one under the slanted attic roof that had filled my teenage years with math homework and the muffled soundtrack of my parents arguing about money. I pressed my palm against the wallpaper and felt the cool plaster hold me like a last quiet thing. If I listened hard enough, I could still hear my mother in the kitchen fifteen years ago, praising Daniel for a report card while I stood in sock feet with a science fair ribbon and a bag of groceries I’d bought with babysitting cash.

It wasn’t that I hadn’t seen this coming. It was that I’d finally stopped telling myself a different story.

Morning lit the room in the particular gray of a winter sky that hasn’t decided whether it loves anyone. I packed deliberately. Clothes, headphones, the records I’d collected one yard sale at a time. Then the things you can’t keep on a shelf: flash drives with scans of old bank statements; photos I’d taken of mail that wasn’t meant for me but had my future in it; recordings of conversations that began gently and hid teeth.

I slid a box out from under my bed—the unnecessary box, the one I kept for the day when I would need to pick up my life and go. It felt lighter than it should have. So did I.

As I moved toward the door with my suitcase, my mother materialized at the bottom of the stairs in a sweater the color of regret disguised as grace.

“You’ll be fine,” she said. “You’re always fine.”

It sounded like a compliment. It sounded like a curse.

“Tell Daniel congratulations on the house,” I said. “It looks good with the lights.”

“We’ll talk about the details after New Year’s,” my father added from the living room, the syllables rubbing against one another like tired gears. “Don’t make this ugly.”

Ugly had already happened. It was hiding in plain sight like a stain scrubbed without soap. I rolled my suitcase out the door and down the sidewalk as the neighbors waved, oblivious to the fact that they were watching a small earthquake disguised as a polite departure.

On the bus to my new apartment—a studio with good light and thin walls—I replayed the last three months. The whispers through thin plaster. The way the family printer had hummed at midnight like it was complicit. The letter I’d found wedged behind the microwave last week: Notice of Mortgage Refinance — Borrower: Daniel Wood. Not “Daniel and Nathan.” Not “Nathan.”

Daniel had never lived at that house. Not since college. But his name had quietly moved in, one line at a time: on the mortgage, the insurance, the savings account that had once been joint and now was only joint when my contribution paid the bills.

There was a sentence in the refinance letter that read like fiction: Title shared with named party. Named. Not son. Not family. Named, like a character who doesn’t know they’re in a plot until the second act.

When I’d asked my mother about it—casual, leaning in the kitchen doorway like I didn’t care about the answer—she had paused for a beat too long and then laughed.

“Oh, he’s just helping out,” she’d said. “You shouldn’t worry about it.”

That was when I’d stopped being their son and become their observer.

Part II — The Quiet Archivist

I don’t know who said revenge is a dish best served cold, but documentation is a dish best cooked slowly. For three months I watched with a patience I hadn’t known was in me.

Daniel’s arrogance was a gift wrapped in shiny paper. He left traces of everything. He reused not-quite-strong passwords and bragged in texts about things that needed silence. He sent emails littered with signatures he didn’t own, attaching scanned forms that still bore the faint watermarks of the original templates he hadn’t bothered to buy.

One night while my parents slept, I logged into my father’s email from the family computer and clicked through the labyrinth. There they were: an insurance policy update bearing my name and Daniel’s signature; a loan application filled with my employment details but the wrong phone number; a letter ostensibly from me to my employer “verifying” my salary for a consolidation loan I had not requested.

I didn’t confront anyone. I didn’t print and wave. I took screenshots. I saved PDFs. I set timestamps. I recorded a voicemail of a bank manager leaving a message for “Mr. Nathan Wood” about “your son Daniel’s request” and my account’s anticipated “automatic transfer” to the new mortgage escrow.

“Don’t transfer any funds without my written authorization,” I said when I returned the call. I recorded that, too.

At night I lay in bed and listened to my parents whisper around the glow of their phones. Once, my father said, “He’s not stupid, Marla.” Once, my mother said, “He’ll never make a fuss.”

Both times, I reached for the little recorder I kept at the back of the drawer under my socks and let it listen to the house.

On the morning I left, I slipped my father’s spare key off the hook in the laundry room and pocketed it. I took the binder that held thirty years of tax returns. I took the spare checkbook from the back of the desk drawer and photographed the serial numbers, then left it where it was. I took the old family camcorder, hidden since Christmas 2002, and stuffed it into my backpack without looking at the tape.

You don’t go to war with weapons you don’t know how to use. You go to war with evidence.

Part III — The Promotion Dinner

Two months after Christmas, my parents mailed embossed invitations to a dinner: Join us in celebrating Daniel’s promotion to Vice President. White cardstock. Gold ink. A lie dressed as a milestone.

I wasn’t invited. Of course not. But the invitation left on the hall table for the mailman to admire had my address on it, and my mother had always taught me that good manners meant never showing up empty-handed.

I bought a box, something with tasteful ribbon, and inside I placed exactly four sheets of paper:

-

The refinance notice with Daniel’s signature.

The loan application with my employment details and his email address.

The insurance update showing my name and his authorization.

A letter I had written myself, addressed to the bank and copied to the police.

I arrived twenty minutes late. The house looked as it always had: doily on the piano, photos arranged on the mantle to suggest our happiness, casserole steam fogging the kitchen window like a suburban sauna.

Daniel opened the door with the grin of a man who had never been told no in a sentence that mattered.

“You came?” he said, like he was the host of a reality show and I was a contestant who had opted not to be edited out.

“I never miss a family event,” I said.

My mother stiffened at the sink. My father rose from his chair and then sat again, like a puppet whose strings had been tangled.

At the table, Daniel held forth on synergy and leadership while my parents laughed on cue. I waited until the second pour of Cabernet and then slid the box across the placemat.

“A little something for your desk,” I said.

He lifted the lid, expecting a pen with his initials or a paperweight shaped like ambition. He stared at the first page. His smile faltered and then put itself back together too late to hide the crack.

“What is this?”

“Proof.”

My mother reached for the paper with the instincts of a woman who has long curated the version of reality she prefers. Her hand shook. My father’s fork scraped the plate like a metal inhalation.

Daniel looked at me the way someone looks at a stray dog that’s unexpectedly bared its teeth.

“You can’t prove—”

“I already did,” I said. I slid the USB drive onto the cloth like a coin in a ritual. “The bank has a copy. So do the police. And tomorrow morning, so will the newspaper. I scheduled it the way you schedule everything—for the maximum effect after dessert.”

My mother whispered, “What have you done?”

I smiled politely. “Put a mirror on the table.”

Daniel’s face did something I had never seen it do: it learned humility. Only for a second. Then it learned fear.

My father stood and then sat and then stood again. “We can fix—”

“No,” I said, surprising myself with how much mercy sounded like ice. “You told me to leave on Christmas because the lie couldn’t hold three people. It barely held two. Now it breaks.”

Daniel lunged for the drive. I leaned back, casual and triangle-balanced in my chair the way you learn to balance on a bus that brakes too often. My mother reached for his arm like a reflex. My father muttered a curse and used my full name the way men use it when they want you to remember who gave it to you.

I left without slamming the door. The night smelled like exhaust and frost. Somewhere a neighbor’s television laughed. On the bus back to my apartment, the lights flickered across the aisle like a Morse code message that I couldn’t read and didn’t need to.

Part IV — The Ruin and the Quiet

People assume aftermath is dramatic. It isn’t. The dramatic part is over in the dining room. After that, consequence is a bureaucracy.

Daniel’s company put him on leave “pending investigation” by 9 a.m. By 5 p.m., a news outlet had posted a story with the gentlest possible headline: Local VP Falsely Listed on Family Mortgage, Police Say. They always make passive voice do the dirty work.

My parents’ mortgage servicer froze their escrow; the bank suspended the line of credit; the title company issued a formal notice of clouded title that read like a weather report predicting permanent overcast.

I didn’t gloat. I slept. For the first time in months, I slept until sunlight made a deliberate decision to land on my face.

There were calls. My mother left voicemails that sounded like recipes with one ingredient missing: apologies without ownership. My father tried once and then texted me three paragraphs that read like corporate-speak about “family unity” and “navigating a challenging moment.”

Daniel didn’t call. He sent one email that said You’re dead to me, and another that said I didn’t think you had it in you. The second one I printed and taped to the inside of my cabinet to read when I doubted myself.

The police asked me for a statement. I gave it to them with my lawyer present, a woman named Carver who had hands like someone who used to play piano and eyes like a person who had chosen to practice law because the world needed rules enforced by patience.

“You’re not pursuing criminal charges?” she asked me when we stepped out into the cool air.

“I’m pursuing distance,” I said. “The rest belongs to gravity.”

I took the settlement money from the civil suit and bought a place by the coast. A little house with tile in the kitchen I would never have dared to choose under my mother’s gaze and with the kind of afternoon light that makes the world forgive itself for an hour.

It was small and it was mine. So were my records, my kitchen knives, my friendships. So were the minutes of silence in which nobody corrected my posture or my version of events.

After a while, the story filtered back in bits, like tide foam carrying shells.

Daniel had been fired, then hired, then fired again. He moved apartments and girlfriends like someone trying to outrun a smell only they could not smell. My parents told the neighbors that I had “run off,” that I had been unstable “for a long time.” They said it with the careful sadness of people who want to be pitied for what they did.

For months, I wrestled with the urge to correct them. At 3 a.m., I drafted a hundred letters to a hundred people who would not care in the way I needed them to. I deleted every one.

The lie they lived in was a self-woven net. Correcting it would only make it tighter around my own throat.

So I let them keep it. I let them keep their version because it was the only house they could afford. Now they are stuck in it the way ivy is stuck to a wall—beautiful from a distance, poisonous up close, destroying what it needs to survive.

Part V — The Tape Under the Bed

Six months after the dinner, on a day when the sea was loud and the radio insisted on songs from a decade I had survived, I unpacked the last box I’d pretended not to see. Inside, beneath a sweater that rubbed like memory, was the old family camcorder.

I held it with my breath held the way you do when you touch fragile things that also destroy you.

The tape was already inside. I pushed it into the dock I’d bought at a thrift store from a man who said it had belonged to a school. The footage jerked and then steadied.

Christmas 2002. The living room looked the same in a way that made my stomach feel like an elevator missing a floor. Daniel, age fifteen, opened a box and held up a leather jacket like a trophy. My mother clapped. My father laughed like a man who had won at something.

Offscreen, my voice asked, “Can we go to Grandma’s now?”

“Don’t interrupt,” my mother said wearily, the kind of weary that comes not from tire but disdain.

I watched my teenage shoulders in a mirror and wanted to put my hands on them. I wanted to say, It’s not that they don’t see you. It’s that they look at you and see the wrong thing, and that is not your failure.

I closed the camcorder. The sun slid across the floor with the indifferent grace of celestial mechanics. I made tea. I decided forgiveness and forgetting were different countries, and I had already chosen my address.

Part VI — The Final Gift

A year to the day after I left, I stood at the edge of the water with my shoes in my hand and the cold folding my ankles into itself. My phone buzzed. A number I hadn’t saved but knew.

I almost didn’t answer. Then I did.

“Nathan,” my father’s voice said. It had aged. Of course it had. I had too. “Your mother and I…we wanted to say… we wish things had gone differently.”

“That would have required different choices,” I said, gently enough to count as love.

“Daniel…” He swallowed. “He’s… he’s had a tough year.”

“I know,” I said.

There was a pause that contained every dinner and every silence and every report card and every bill. Somewhere in it a seagull laughed at us all.

“I hope you’re well,” he said finally.

“I am,” I said. “I hope you are too.”

After I hung up, I stood in the noise of the sea and realized something that felt like a confession: I wasn’t interested in their remorse. I wasn’t even invested in their ruin anymore. I was interested in my own quiet.

People say revenge is loud, dramatic, explosive. It can be. Sometimes it should be. But the best kind is surgical. It removes what is killing you and leaves a scar that only you see when you undress. It lets you walk away while the people who lied about you keep living in the story they told, trapped by a narrative they wrote to punish you and ended up wearing like a shroud.

I didn’t just move out of that house. I moved out of the lie they built.

Now they are stuck in it. I am not.

On my kitchen shelf sits a small glass jar with sand in it and a folded note: Really? It reminds me of the night I answered a sentence with a question. It reminds me that calm can be a weapon if you hold it like a blade. It reminds me that sometimes the most generous thing you can do for a family that survives by pretending is to leave them to their pretenses and go build a life in the open air.

When the light moves across the room in the late afternoon, it knows where to land. On the records. On the bills paid in my own name. On the flash drives that I no longer need to touch. On the quiet, which has become a companion instead of a punishment.

Merry Christmas, I tell the empty room. And for the first time, I mean it.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. After my mother chose my stepfather over me, I was forced to live on the streets at 16. “He’s not worth the trouble,” she said. I cleaned toilets for money. Monday, a detective found me: “Your real father in Germany spent millions searching for you. He left his automobile empire worth $2.1 billion -to claim it, you have 72 hours to your family’s darkest secret”

After my mother chose my stepfather over me, I was forced to live on the streets at 16. “He’s not…

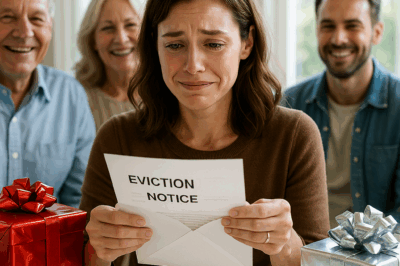

CH2. On My Birthday, My Family Gave Me A ‘Special’ Present. When I Opened It, It Was an Eviction Notice for My Own House. I Smiled as I Returned the Favor on Their Wedding Day…

My Family Gave Me an Eviction Notice on My Birthday. I Smiled as I Returned the Favor on Their Wedding…

CH2. My Dad Sent Me $3,500 Allowance But Mom Sent to My “Golden Sister” for Her Dream—Until I Collapsed…

My Dad Sent Me $3,500 Allowance But Mom Sent It to My “Golden Sister” for Her Dream—Until I Collapsed… …

CH2. At 27, My Parents Tried Controlling Me Again — Big Mistake

At 27, My Parents Tried Controlling Me Again — Big Mistake Part I — The Invitation With a…

CH2. My Family Told My Sister’s Kids To Eat First And Told My Kids To Wait To Share The Crumbs.

My Family Told My Sister’s Kids To Eat First And Told My Kids To Wait To Share The Crumbs …

CH2. My Mom Handed Me A Glass Of Red Wine With A Strange Smile At My Engagement Party It Smelled Off I Swapped It With My Sister Thirty Minutes Later She Collapsed And..

My Mom Handed Me A Glass Of Red Wine With A Strange Smile At My Engagement Party. It Smelled Off….

End of content

No more pages to load