Why One U.S. Submarine Sank 7 Carriers in 6 Months — Japan Was Speechless

The Pacific in early 1944 didn’t feel like anyone’s lake anymore.

Not to the men who sailed on it. And certainly not to the men who hunted beneath it.

Eighty feet down in a steel tube the length of a football field, Lieutenant Commander Oscar E. Hagberg stood hunched over a glowing plot table, listening to the faint murmur of voices and the steady, almost reassuring hum of USS Albacore’s electric motors.

The air was stale. It always was down here. Sweat, oil, metal, coffee, and a hint of fear—distilled and recycled with every breath.

“Skipper,” said his executive officer, Lieutenant James Ashley, leaning in close so he didn’t have to raise his voice. “If our intel boys are right, we’re parked dead center in the middle of a highway.”

Ashley tapped the chart with a pencil. A narrow corridor was marked between two patches of reef, like a funnel drawn on endless blue.

“Every carrier running away from Truk has to pass through here,” he said quietly. “They don’t have a choice.”

The date was February 19, 1944. The position was roughly two hundred miles northeast of Truk Lagoon—the heavily fortified atoll Japanese planners had once called their Gibraltar, their Pearl Harbor of the Central Pacific.

Two days earlier, that “Gibraltar” had been hammered.

Operation Hailstone. More than five hundred planes from American fast carriers had pounded Truk until the lagoon churned with burning ships and leaking oil. Transports, cruisers, auxiliaries—caught at anchor and smashed. Those who could still move had fled in all directions, smoke trailing behind them like guilty thoughts.

Somewhere out there, Hagberg knew, Japan’s remaining carriers were running.

And Albacore was waiting, quiet as a loaded spring, in the one stretch of ocean they could not avoid.

It had taken three hard years to create this moment.

When America first stumbled into war in 1941, its submarine force had been a cruel joke. The boats themselves—fleet submarines like Albacore—were good steel, well-designed. The crews were brave, mostly volunteers drawn by extra pay and the appeal of hunting below the surface.

The problem was the weapon at the heart of their trade.

The Mark 14 torpedo.

On paper, it was a beautiful machine. Steam-driven, fast, long-ranged, with dual detonators—one to explode under a ship’s keel using magnetic influence, another to explode on direct contact. It was supposed to punch holes in anything afloat.

In practice, it was a saboteur that worked for the enemy.

It ran deeper than it was set. It passed under targets entirely. When it did hit, it often failed to explode. And sometimes the guidance went haywire, sending the torpedo into wild circles that occasionally looped back toward the submarine that had fired it.

The men who went out in those early patrols came back with rage written on their faces and failure stamped in their patrol reports.

They’d risked their lives closing on convoys, set up perfect attacks, fired spreads of fish that should have turned tankers and freighters into wreckage—and watched most of them run wide or go thud against hulls.

From Pearl Harbor, the Bureau of Ordnance shrugged.

The torpedoes were fine, they said.

The commanders must be firing wrong.

In July 1943, one of those commanders finally refused to accept the lie.

Commander Lawrence Daspit took USS Tinosa in against the big tanker Tonan Maru No. 3—a fat, valuable target. He fired. Hit. No explosions. Fired again. Again. Again.

Fifteen torpedoes left Tinosa’s tubes. Eleven struck home, one after another, each a potential kill shot.

Not one detonated properly.

The tanker, battered but not broken, staggered away.

Daspit saved the last torpedo in his boat.

He brought it back to Pearl like a prosecutor carrying his prime exhibit.

He demanded that the torpedo be tested.

When they fired it against a cliff, it hit and did… nothing.

At last, the bureaucracy had to admit what the men on the front line had known for two years:

The Mark 14 was a mess.

By early 1944, those issues were finally being beaten out of the weapon—depth settings corrected, faulty magnetic exploders disabled, contact pistols redesigned. It had taken shame, anger, and more wasted opportunities than any man liked to think about.

Albacore, sailing on her sixth war patrol out of Pearl Harbor in January 1944, carried torpedoes that actually did what their manuals claimed.

They ran at the right depth. They exploded when they should. They carried 600-pound warheads capable of snapping a ship’s spine.

And in Hagberg, those weapons had found exactly the kind of mind they needed.

Submarine command wasn’t for the loudest man in the room, or the bravest, or even the smartest in the traditional way.

It demanded someone who could do algebra while dying, someone who could stare at a series of bearings and ranges and see, in his head, where an enemy would be fifteen minutes from now—not where he was.

It called for a mix of cold patience and instant nerve. Too cautious, and you never got within range. Too impulsive, and you got your boat—and sixty men who trusted you—killed.

By 1944, the selection process had sharpened to a razor.

Men who hesitated were relieved. Men who took foolish chances were relieved—if they survived. The ones who remained in command of front-line boats had been through the fire.

Hagberg was one of those survivors.

He had learned his craft in the dark early days off the Philippines and in the island-studded Philippine Sea, had felt defective torpedoes run cold beneath his targets and had seen merchantmen slip away because his weapons had betrayed him. When the fixes finally came through, he embraced them not as gifts but as overdue apologies.

Now, in Albacore’s cramped control room, he stood in front of a glowing radar repeater, his hand unconsciously tightening on the chart table as the operator called out:

“Contact bearing two-eight-five. Range eighteen thousand yards. Large. Multiple smaller echoes in company.”

Around him, voices rose in controlled cadence.

“Battle stations—torpedo,” Hagberg said, his own voice level.

Alarms muffled to preserve stealth. Men moved. Doors sealed. Red lights glowed.

In the forward torpedo room, the crew swung Mark 14s into place, dogged outer doors open, checked gyro angles. Each of those blunt-nosed cylinders weighed over 3,000 pounds. Each one was a shot they might never get again.

In the control room, the Torpedo Data Computer—an electro-mechanical analog brain the size of a couple of suitcases—whirred and clicked as bearings and ranges were fed in, spinning gears to calculate future positions for future shots.

Hagberg climbed the ladder to the conning tower and wrapped his hands around the periscope handles, the metal cool under his palms.

“Up scope,” he ordered.

The periscope slid upward, water sheeting off the lens. He brought it to his eyes and rotated slowly through gray-green ocean until the distant shapes he’d already seen in his mind came into sharp relief.

He levelled on the largest one.

Even at long range, he could feel its weight.

Long, flat deck. Island superstructure. Planes spotted. Wake boiling.

“Carrier,” he said. “Big one. Escorts: four destroyers. Speed… call it twenty-four knots. Zigzagging.”

He watched her swing lazily through her pattern—port, then starboard, then straight.

Zigzags were meant to turn a torpedo’s straight line into a wasted line, to make it impossible to predict where a ship would be by the time a shot arrived.

No pattern was truly random.

Hagberg had spent too many periscope hours watching Japanese zigzags not to recognize their habits. Each ship, each captain, had a preferred rhythm. You learned to listen for it.

The hunt took hours.

Surface, sprint, dive as an escort’s sonar cone swept past. Let them go. Surface again, close the range, slip along the edge of their awareness. Again and again, Albacore ghosted in toward the path of the fleeing carrier.

The ocean was wide, but not wide enough to hide forever.

At 0612, after two hours of stalking, the carrier steadied on a southwesterly course.

For a brief window—minutes at most—she ran straight.

Full broadside.

“Range eighteen hundred,” Ashley reported from the TDC. “Angle on the bow, ninety degrees. Target speed twenty-four knots.”

Perfect. Difficult in theory, but in practice as good a shot as the ocean ever offered.

Hagberg’s voice stayed steady.

“Flood tubes one through six,” he said.

The torpedo room reported ready.

“Stand by… fire one.”

The boat shuddered as compressed air punched the first torpedo out of its tube and into the sea. The men aboard felt it in their feet and teeth—that subtle change in vibration they could never quite get used to.

“Fire two.”

Eight seconds.

“Fire three.”

Eight seconds more.

He walked the salvo down the length of the target’s projected path, giving each fish a slightly different aim point.

“Fire four. Fire five. Fire six.”

Six lines of steel and TNT streaked away under the surface, racing at forty-odd knots.

Now came the worst part.

“Take her deep,” Hagberg ordered. “Rig for depth charge.”

The diving officer pushed her down. Seventy feet. Ninety. One hundred and fifty. Two hundred. Gauges crept. The light changed as the last hints of dawn fell away.

In that compressed space, moments stretched.

You listened.

You waited.

If nothing happened—if those six perfect shots ran dumb or went under or glanced and failed—it wasn’t just another tactical failure.

It was trust broken again. In the weapon. In the war. In the idea that any of this mattered beyond the fact that you were far from home in a tube that could become a coffin.

The first explosion came right when the mental math said it should.

Seventy-two seconds after firing.

A dull, heavy thump through two hundred feet of water, followed by a distant rumble and a faint, rising sound that could only be tearing metal and the sudden intrusion of the sea where it didn’t belong.

A second blast chased the first.

Then a third.

Three detonations. Out of six torpedoes.

Against a zigzagging carrier under escort, that was a hunter’s dream.

Around them, destroyers went mad.

Sonar pings multiplied, harsh and insistent, echoing through the hull. Engines above changed note as escorts whipped their bows around and charged, trying to run down the unseen attacker.

“Here they come,” Ashley murmured.

Depth charges fell, strings of them, each one a steel drum of hate.

The ocean above Albacore bloomed in white and black as explosives went off in patterns, walking down guessed track lines.

Inside the submarine, each explosion slammed the hull like the fist of a god.

Bulkheads groaned.

Light bulbs vibrated in their sockets, some shattering.

Dust and flecks of cork insulation drifted down from the overhead like gray snow.

In the forward torpedo room, a young torpedoman named Robert Chen clamped his jaws around the edge of a bucket, spat bile, then laughed weakly as he wiped his face.

“Not seasick,” he told the man next to him. “Just… enthusiastic.”

No one believed him, and no one cared.

They were all busy praying, cursing, or staring fixedly at gauges, depending on temperament.

Forty-five minutes later, the pattern changed.

The charges grew more distant, the pings wider apart.

The destroyers were turning back.

Their charge—the big, wounded animal above—demanded their attention.

By the time Hagberg dared to bring Albacore back up to periscope depth, the horizon was empty of ships.

But not empty.

Oil slicks spread in the dawning light, rainbow stains on gray water. Planks, crates, and lifejackets bobbed in the swell. A few dark shapes moved weakly among the debris—survivors clinging to anything that floated.

Hagberg watched for a long moment, jaw tight, then lowered the scope.

“Mark the position,” he said.

They put pencil on chart.

One carrier down.

He did not know her name yet. Later, they would learn she had been a light carrier—the 8,500-ton Chūyō-class ship that American records would call Aikoku Maru’s cousin, and Japanese records called Aso or Aikoku’s sister—depending on who you asked. She had gone down with more than seven hundred of her crew.

At that moment, to Albacore, she had been Target Number 1.

They moved on.

News of the sinking reached Tokyo days later via crisp, impersonal signals.

“Light carrier lost in Central Pacific,” the admiralty log recorded. “Cause: torpedo attack. Estimated aircraft lost: thirty. Personnel: approximately seven hundred.”

It was another entry in a list that had grown worryingly long since 1942.

Early in the war, carriers had been the weapon.

The sword.

At Pearl Harbor, they had carried the strike that announced Japan’s reach. At Coral Sea, Midway, the Eastern Solomons, Santa Cruz—they had been the fists thrown in every direction.

Now those fists were being cut off wrist by wrist.

Aso—whatever the name scribes put down—was not a frontline fleet carrier like Shōkaku or Zuikaku. She was a light carrier, used for transport and training. But every flight deck lost was a wound now, every hangar below wasted steel.

Japanese admirals noted the loss with grim faces.

No one thought this was the work of a single submarine.

That would have been absurd.

Submarines sank freighters. Tankers. Occasionally a cruiser. But a carrier?

That was an accident.

A one-off.

They were wrong.

The Americans had been learning too.

By 1944, Admiral Charles Lockwood—Commander, Submarines, Pacific Fleet—had turned his arm of the Navy into something Japan did not truly acknowledge until it was too late.

He’d done it by attacking three problems at once.

The first was hardware. He forced the Bureau of Ordnance to admit its mistakes, saw the Mark 14’s defects identified and corrected, demanded that the pendulum finally swing from excuses to results.

The second was tactics. Early doctrine had scattered submarines in defined patrol boxes, as if they were static pickets waiting for targets to blunder by. Lockwood and his staff, working with newly available intelligence, began moving them like a pack of wolves instead, placing boats in choke points and converging them on juicy convoys.

The third was sight.

In Pearl Harbor, in darkened rooms filled with cigarette smoke and squinting eyes, American codebreakers had gone to war with pencil and paper against the Japanese naval cipher JN-25. By March 1944, they had rashed that code open like a rotten fruit.

Station HYPO, as the Pearl decoding center was called, could read much of Japan’s naval traffic within hours of its transmission. When a carrier left Yokosuka, they knew. When a convoy was organized out of Singapore, they knew. When orders went out to concentrate fleets here or there for some grand plan, they knew that too, or could guess.

Lockwood took this information and did something unforgivable in the eyes of his enemy:

He used it.

He vectored submarines into shipping lanes before the ships were in them. He placed boats like Albacore in the path of carriers days before those carriers arrived, like a chess player putting a piece on a square where a queen would one day step.

By the time Hagberg and Albacore finished refuel and rearm at Pearl and headed back out, the war had become a kind of long-range ambush.

And for six months, Albacore would be one of its sharpest blades.

March 29, 1944, dawned like any other in the vast central Pacific.

Sky blue. Sea blue. The line between them slightly smudged.

Three hundred feet down, Albacore’s world was all shadows and instruments.

Ultra intercepts had whispered about a “flying crane” leaving Japan in a hurry—cryptic code words and vague references. Analysts believed it meant a carrier was shifting south, perhaps to reinforce bases in the Marianas or the Philippines.

Lockwood penciled a line on a map from the Japanese home islands toward the south.

He put Albacore on that line.

At 1423 hours, the submarine’s radar operator called out a contact: a strong return at twenty-four thousand yards, with smaller echoes clustered around it.

Hagberg was in the conning tower in seconds.

He eased the periscope up and turned slowly.

On the horizon, blurred by distance but unmistakable, ran a task group.

Four destroyers screened ahead and off the flanks. In their midst, a long flat shape knifed through the water at high speed, its bow throwing white water aside.

A big carrier.

“Escort pattern looks tight,” Ashley said beside him, peering at the radar repeater. “Speed twenty-six knots. Same old story—too fast for a stern chase.”

That was the trick.

Albacore, even at full surface power, could barely make twenty-one knots. You couldn’t catch a carrier like that by following it. You had to guess where it would be, move toward that point, and be there before it arrived.

It was geometry, not heroics.

For six hours, that was all it was.

Bearings. Ranges. Stopwatch clicks.

Up to periscope depth to get an angle and a solid reading. Down to avoid detection. Surface at a distance to sprint ahead, the diesel engines roaring hard enough to set the hull trembling. Back down before some wandering floatplane or overly curious destroyer spotted a feather of wake on the horizon.

Ashley and the fire control party fed numbers into the TDC, calculating possible tracks, trying to reduce guesswork to inevitability.

By 1900 hours, as evening deepened and the tropical sky turned from blue to indigo, Hagberg made his decision.

They would not take a long-range chance.

They would cut it close.

At twenty-thirteen, with the carrier still a distant blur, Albacore surged up into the fading light.

All four main engines kicked to life. The smell of hot diesel filled the boat as men at the throttles shoved them forward.

The submarine sprinted across the ocean, bare deck awash, bow throwing white spray.

Lookouts posted on the bridge swept the sky for aircraft. One spotted a speck, called it, tracked it until it faded west. No reaction. No bombers overhead.

They were running ahead of a storm they could not see, racing to cross a line on the ocean before something unimaginably large crossed it first.

Fifteen minutes later, they were where the TDC said they must be.

“Dive,” Hagberg ordered.

Albacore crashed from surface to periscope depth in forty-five seconds, angle steep, ballast tanks drinking seawater as if they had been waiting for thirst to be quenched.

At sixty feet, the planesman levelled her off.

“Steady,” he muttered through clenched teeth.

Then the sonar man’s voice came:

“Target passing overhead. Range close. Very close.”

Hagberg raised the periscope.

For a heartbeat, the lens filled with nothing but gray-green water.

Then the carrier slid into view like some metal island in motion.

She was huge.

Flight deck stretching like a highway. Island structure bristling with antennae. Aft, the churn of propellers boiled the water into white chaos.

“Range twelve hundred yards,” Ashley whispered, hardly daring to breathe.

At that distance, a destroyer’s sonar should have found them. But the carrier herself was making so much noise—her screws churning, her hull slicing, her machinery vibrating—that she cast a cone of sound behind her. In that “shadow,” for a few moments, the submarine was all but invisible acoustically.

Hagberg had put Albacore in the one place where she could be both unseen and deadly.

“Set up four,” he said. “Spread along her length.”

“Solutions ready,” came the immediate answer.

“Fire one.”

The torpedo jumped away.

“Fire two. Fire three. Fire four.”

He kept the periscope up, unwilling to blink.

The first hit took the carrier under the forward elevator.

A tower of water and debris rose higher than the flight deck, then collapsed back in a white curtain.

The second hit near the island, erupting in a gout of flame and spray.

The third smashed into her aft, somewhere near the machinery spaces and shafts.

Three hits.

You didn’t get better than that against a moving giant.

The carrier lurched, her bow swinging.

Already, Hagberg could see a list developing—slight at first, then more pronounced.

He did not stay to watch her die.

“Down scope,” he snapped. “Take her deep. Prepare for counterattack.”

Above them, the destroyers split and ran, their captains making their own decisions in a chaos magnified by radio silence. One charged north, another south, a third weaving uselessly in circles.

Only one remained close enough to try a proper attack.

By the time that destroyer organized a depth-charge pattern, Albacore had already slid further down and away, nosing toward the bottom, hiding in thermoclines where warm and cool water layers bent sound.

The carrier they had struck—a Hiyō-class ship, they would later learn, named Taiyō or Unyō or Jun’yō depending on whose report you read—rolled and capsized fifty-odd minutes after the torpedoes hit.

On the periscope film, when they could later review it, she could be seen hanging on her beam end for a long moment, a grotesque, wounded thing, before rolling over and disappearing.

More men and aircraft gone.

More steel in the deep.

Albacore added another mark to her chart.

Two carriers in five weeks.

They were not flukes anymore.

They were a pattern.

By April, the pattern had become something more.

A reputation.

Albacore roamed the convoy routes between Japan and its fraying empire, slipping along shipping lanes like a shark under an overcrowded surf.

Guided by Ultra, Hagberg positioned his boat not where ships were, but where they would be.

Light carriers pressed into escort duty, their flight decks stripped for extra cargo, moved along predictable courses between Yokosuka, Saipan, and the Philippines. Converted passenger liners with flight decks—escort carriers—shuttled aircraft and fuel.

On April 17th, a small Japanese carrier, Un’yō, found Albacore waiting.

She was a lighter vessel, carrying fewer planes than the fleet carriers, but no less precious now. Hagberg watched her thread through her zigzags in a long afternoon’s game.

Two torpedoes punched into her from two thousand yards.

She rolled and sank within forty minutes, taking down more men whose names the Americans would never know.

On May 3rd, another converted carrier—Taiyō, once a civilian liner plying peaceful routes—caught three hits from Albacore off Okinawa. Burning, listing, she went down in relatively shallow water, her loss a local tragedy and another strategic wound.

End of May.

Another rumor from Ultra: Zuikaku, veteran of Pearl Harbor, Coral Sea, Santa Cruz, pride of the surviving Japanese fleet, moving through coastal seas.

Hagberg found her.

He attacked from unfriendly water, near shoals and close to land-based air.

Two torpedoes struck her, jerking her whole massive hull sideways. She did not sink—Zuikaku was tough—but the damage forced her back to Yokosuka for months of repair at a time when Japan could not spare even days.

Each attack followed the same choreography.

Long patience.

Sudden violence.

Immediate disappearance.

Hagberg did not surface to see the whites of any man’s eyes. He did not linger to watch the final roll or hear the last cries. His duty was not to bear witness.

It was to keep killing carriers until there were none left to kill.

By June 1944, Albacore had become something like a bad dream for Japanese admirals.

Reports from shattered carrier groups mentioned a submarine that seemed to appear from nowhere, launch salvos that found their mark, and fade away before escorts could get a bearing.

In Tokyo’s naval intelligence offices, staff officers began to suspect a trick.

Perhaps “Albacore” was not one boat.

Perhaps the Americans were cycling several submarines under the same name, attributing multiple sinkings to one hull to confuse them.

The alternative—one submarine doing all this—was somehow harder to accept than the idea that American cryptographers were listening to their every word.

They convened committees, wrote memoranda, reassigned destroyers to escort duty, revised doctrine.

They did not find an answer.

There may not have been one.

June 1944 was supposed to be Japan’s answer.

As American troops stormed ashore on Saipan, halting within sight of Japanese soil’s reddish hills, the Imperial Navy gathered its remaining strength for what it termed the “decisive battle.”

In the Philippine Sea, they would meet the American carrier fleets.

They would throw every remaining plane, every pilot, every carrier into a punch that would make Midway look like an opening round.

It was desperation philosophy—the belief that one great stroke could reverse two years of losses.

Admiral Jisaburō Ozawa’s Mobile Fleet steamed from Tawi-Tawi and other anchorages, gathering carriers and battleships. Others, slower or delayed, left Japan itself and headed south as fast as boilers and hulls would allow, racing to join the main body.

New among them was Taihō.

She was Japan’s pride. The first of a new class of armored fleet carriers, with an enclosed hangar and heavy deck plating designed to shrug off bomb hits that had gutted earlier ships. Displacing nearly 38,000 tons at full load, she carried around seventy-five aircraft and a deeper symbolic weight.

If older carriers like Shōkaku and Zuikaku were aging lions, Taihō was the young tiger.

On June 19th, as American and Japanese air groups closed in on each other in what would become known as the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot, Taihō slipped south of the main battle area, her captain anxious to bring his ship into range, her escorts tense.

She refreshed fuel and aviation supplies.

She steamed on.

And in the blue depths ahead of her, Albacore waited.

The morning was clear.

Sky like a dome of hot glass. Sea calm enough that small waves looked almost painted on.

In the control room of Albacore, the sonar man listened to a sound that did not belong to water alone.

Faint at first. A steady thrum, low-pitched, rhythmic.

Propellers.

Big ones.

“Multiple screws,” he reported. “High speed. Bearing… zero-eight-five. Closing.”

Radar, when they dared surface briefly to check, confirmed a cluster of ships.

Hagberg brought the boat back down, conserving battery.

They listened more.

The engine note grew, split, resolved into multiple tones.

Escorts. And one heavier beat—slower, deeper, pulsing like a giant heart.

“Carrier,” Ashley said softly.

They were south of the main fleet, right where Lockwood’s orders had placed them—to catch the stragglers, the latecomers, the ships running behind schedule.

Taihō and her escorts bore down the line, oblivious.

At 0900, Albacore lay quietly at eighty feet, her systems rigged for silent running. No unnecessary clatter. No loud talk. Crewmen moved like ghosts, gently, controlling their own breathing through force of habit and fear.

Six torpedoes had been loaded into the bow tubes.

Six.

All of them Hagberg meant to fire.

He went up the ladder to the conning tower, felt the metal warm under his hands.

“Up scope,” he ordered.

The periscope broke the surface briefly, sending up the faintest ripple.

He swung it in a slow, deliberate arc.

There she was.

Beautiful, in the terrible way of war machines. Her flight deck rose above the waves, spotted with planes. Her island bristled with antennae and masts. The white bow wave flared, then ran down her sides in long currents. Around her, three destroyers cut their own wakes.

“Range three thousand yards,” Ashley said from below. “Angle on the bow one-five, target speed twenty-four knots.”

Closing.

For a second, Hagberg simply watched.

He felt a strange tug—something like awe. He knew the silhouette. The intelligence summaries had called her Japan’s most advanced carrier. Her armored deck and modern design had been studied in grainy reconnaissance photos pinned to wardroom bulkheads.

Now she was here.

A target.

“Set up a six-torpedo spread,” he said. “Walk it from bow to stern.”

“Solutions ready.”

Hagberg took one more look.

“Fire one.”

The boat lurched.

“Fire two. Three. Four. Five. Six.”

Six steel spears leaped from their tubes and fanned out under the surface.

“Take her deep,” Hagberg said. He didn’t wait to watch. “Ahead slow. Rig for depth charge.”

He had been in enough fights to know what came next.

Above, the escorts were already reacting, sonar operators pricking up their ears at the sudden noises.

At 0908, one of Albacore’s torpedoes slammed into Taihō just forward of the island.

The deck shuddered. Hangar doors rattled in their tracks. In compartments below, men were thrown off their feet. Aviation fuel lines, running beneath deck plates, ruptured. Fuel splashed into spaces it should never have reached.

It was a good hit.

It was not, by itself, a killing blow against a ship like Taihō.

Captain Tomotsu Kaku, on the bridge, steadied himself. He demanded damage reports. They came back patchy but hopeful.

One torpedo.

Flooding but contained.

Speed reduced slightly.

Ammunition stores safe.

The armor and compartmentalization had done their job.

Taihō could fight on.

Kaku decided to maintain course. He had been told this battle might decide the fate of the inner defense line. His brief was to bring Taihō’s air group into it.

Down below, in compartments filling slowly with vapor rather than liquid, a different battle was beginning.

Fuel fumes seeped into spaces where men worked and slept. Ventilation systems, damaged by the blast, were compromised. The ship’s internal airflow became a patchwork of stale, breathable air and sweet, invisible gas.

Somewhere in the damage control chain, an order was given:

Increase ventilation.

Fans spun up.

Instead of evacuating fumes from damaged compartments overboard, the system sucked them in and pushed them deeper into the ship.

Invisible fire.

It spread with every breath of the fans.

On Albacore, at four hundred and fifty feet, men clung to pipes and held their teeth together as depth charges tried to shake them into scrap.

Patterns of bombs rolled off three destroyers in succession. Each string of charges chased a guess, an echo, an old bearing. Each detonation rolled through the hull like thunder through a drum.

In the forward torpedo room, a seam in a casing split. A pencil-thin stream of water hissed in, stinging like glass where it hit skin. Two torpedomen slapped rags over it, pressing their bodies against the leak while others fetched clamps and patches.

In the engine rooms, gauges trembled, needles dancing under repeated concussions. The chief machinist’s mate ran his fingers along pipes and valves, feeling for hairline cracks, listening for changes in pitch.

The attack went on for hours.

Forty depth charges in eight patterns.

For the men aboard Albacore, time became a series of explosions and the spaces between them.

At one point, Ashley looked at Hagberg in the dim red gloom and said, very quietly, “They’re getting better.”

Hagberg grunted.

“So are we,” he said.

He used everything he knew.

He let Albacore sink into a thermal layer where water of different temperatures met and bent sonar pulses. He adjusted her angle to slide along the underwater slope, letting the bottom reflect and confuse echoes. He ordered bits of trash ejected—empty oil cans, slivers of wood—to create false targets.

Eventually, even anger runs out.

The destroyers, low on depth charges and needed elsewhere, turned back toward their wounded carrier.

At 11:47, the last charges fell.

By then, Albacore had crept miles away at two knots, a battered, intact ghost.

Hagberg had no idea whether his torpedo had merely wounded or eventually killed.

He did know that if Taihō survived, she would carry scars he’d put there.

That was enough for the moment.

He marked the attack in his log, noted the bearing, the estimated speed, the time.

He left the rest to the future—and to physics.

On Taihō, the future arrived at 14:32.

For more than five hours, the ship limped on, moving with the fleet, her air group still operating. Pilots flew off her deck into the great chaos of the Philippine Sea. Some returned. Others did not.

Down in the hangars and below, heat grew.

Fuel vapors thickened.

Men complained of headaches, of dizziness.

Somewhere in the belly of the ship, a junior officer flipped a switch, energizing an electrical connection that produced a tiny, almost invisible spark.

In a different context, it would have been nothing.

Here, in an atmosphere loaded with gasoline vapor, it was the match thrown into a powder magazine.

The explosion was instantaneous and overwhelming.

It ripped through compartments from bow to stern, a series of fireballs that sought every pocket of fuel-saturated air. Bulkheads blew out. Steel warped. Men died where they stood, lungs and eyes and skin consumed in a burst of white-hot flame.

On the flight deck, crewmen felt the ship suddenly hunch beneath them.

Smoke and fire burst from vents. Flames licked through elevator wells. The armored deck, immune to bombs, did nothing to stop what had already happened below it.

Taihō, supposedly unsinkable, had been turned into a bomb by one torpedo and a chain of human errors.

At 15:28, she rolled over.

At 15:32, she slid beneath the surface, taking around sixteen hundred of her crew with her.

The decisive battle that Japanese planners had dreamed of was still being fought above, where American Hellcats were making kindling out of Japan’s remaining naval air power in the “Turkey Shoot.”

But for those who care about the quiet, unseen fulcrums on which wars turn, the more telling event that day was the death of Taihō.

One torpedo from one submarine had eliminated the newest, most modern carrier in the Imperial Navy.

When word of Taihō’s loss reached Tokyo, Admiral Soemu Toyoda, commander of the Combined Fleet, read the report in silence.

Japan’s naval strategy had always relied on the idea of a decisive fleet action. Carriers were now central to that idea.

Carriers required safety of movement.

Safety of movement required control of the seas.

Submarines, once dismissed as nuisances, were making a mockery of that logic.

Toyoda’s after-action comments were terse.

“We cannot fight submarines,” he said. “We cannot protect carriers from submarines. We cannot replace carriers lost to submarines.”

The admission was as rare as it was bleak.

The war, he was beginning to realize, was being lost not only in grand clashes of air groups, but in the patient work of hunters the Japanese rarely saw.

On July 8, 1944, USS Albacore slid back into Pearl Harbor, her paint scarred by salt and depth charges, her insides tired in ways no camera could capture.

As she eased up to the pier, her crew lined the deck in faded dungarees, faces gaunt and tanned, eyes bright.

Admiral Lockwood stood waiting.

He had a sheet of paper in his hand. The signals from various sources had been merged, cross-checked, and confirmed.

Aso. Taiyō. Un’yō. Another Taiyō, the escort carrier. Zuikaku damaged. Others crippled.

And Taihō.

Seven carriers destroyed or put out of action in six months by one submarine.

By tonnage, by effect, by sheer concentration of damage inflicted on Japan’s most precious naval assets, Albacore’s patrols in the first half of 1944 had no equal in submarine history.

Lockwood walked to the foot of the gangplank as Hagberg came down.

The two men shook hands.

“Nice patrol, Oscar,” Lockwood said quietly, for once running out of superlatives.

“Yes, sir,” Hagberg answered, equally understated.

There would be medals. Hagberg would be awarded the Navy Cross. The crew would get their combat insignia, their citations. Within the submarine force, they would get something more valuable: every young skipper studying patrol reports would read “Albacore, SS-218” at the top of those pages and pay attention.

They had proven something that would be carved into doctrine.

Submarines were not just raiders of merchant shipping.

They were slayers of capital ships.

In Tokyo’s naval staff building, officers pored over their own grim set of numbers.

Before the war, Japan had ten fleet carriers.

By mid-1944, losses at Coral Sea, Midway, Santa Cruz, and elsewhere had whittled that number down. Ships like Kaga, Akagi, Sōryū, Hiryū were gone. Shōkaku would fall to another American submarine, USS Cavalla, that same June.

Albacore’s patrols had claimed several more, either permanently or temporarily.

Thirty-eight thousand tons here. Twenty-four thousand there. Eight thousand somewhere else.

Each ton was steel bent to purpose. Each plane lost was not just aluminum and rubber, but a pilot who had taken years to train—years Japan no longer had.

Toyoda and his staff tried to adjust.

They assigned more destroyers to escort duty, thinning other formations.

They varied routes, trying to avoid the killing grounds that Ultra had already mapped.

They experimented with new sonar tactics.

The fundamental problem remained.

You can armor a deck against bombs.

You can thicken a belt against shells.

You cannot armor the sea.

A torpedo that finds your hull in the right place cares nothing for doctrines.

American submarines—Albacore foremost among them—had been given accurate weapons, good intelligence, and commanders trained to use both.

The result was simple, terrible math.

By the end of the war, American subs would sink over half of Japan’s merchant fleet and a third of its warships, including more than twenty carriers.

But in that bloody tally, one six-month period stood out:

Albacore’s reign as the Pacific’s most lethal carrier killer.

Albacore herself would not live to see the war’s end.

In late 1944, reassigned to the waters off northern Japan, she disappeared.

Japanese records examined after the war indicated that a submarine had struck a mine off Hokkaido on October 7, 1944, and gone down with all hands.

No distress call.

No survivors.

Just a sudden emptiness where, for three years, there had been a predator.

News of her loss hit the submarine force hard.

Men who had served on her moved to other boats. Hagberg, promoted and brought ashore to teach the next generation, found his own ways to honor what his old command had done.

In time, the war ended.

The carriers that remained in Japanese hands were scuttled or surrendered, their decks silent.

The Pacific, once viewed in Tokyo as an imperial lake, now bore the wakes of American ships unchallenged.

Years later, Admiral Toyoda would write his memoirs with the restraint of an old officer who had seen too much to indulge in theatrics.

“We thought carriers made us invincible,” he admitted. “American submarines taught us that nothing is invincible.”

He reflected on Midway, on Leyte Gulf, on the great surface actions and air battles where ships died in the glare of cameras and the gaze of thousands.

Then he wrote something more quiet, more damning.

“The war was lost,” he said, “not only in great battles, but in the steady elimination of carriers by submarines we never saw until it was too late.”

He didn’t always name them.

He didn’t have to.

In the records, in the killed-in-action lists, in the log entries that simply stopped, they were there.

USS Albacore.

SS-218.

The boat that had taken seven carriers out of one navy in half a year.

For the men in Japanese wardrooms who had watched their world sink beneath them, there came a point when there were no more explanations to offer, no more speeches to make.

They were left with the knowledge that they had been hunted, relentlessly, by an enemy they had underestimated.

And when they looked over the blue water where their carriers had once sailed, the feeling, if they were honest, was not just bitterness.

It was speechlessness.

Because sometimes there is, truly, nothing left to say.

News

CH2. German Commander’s Last 90 Seconds – The Weapon That Destroyed 47 U-Boats

German Commander’s Last 90 Seconds – The Weapon That Destroyed 47 U-Boats The sea looked wrong. Kapitanleutnant Bernhard Müller had…

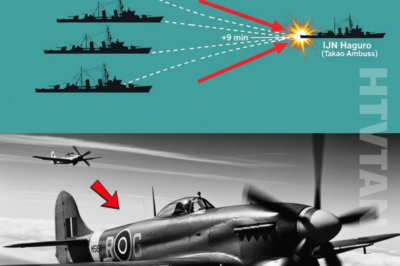

CH2. The 9 Minutes Haguro Never Got Back — When One Missed Warning Triggered the Entire Ambush

The 9 Minutes Haguro Never Got Back — When One Missed Warning Triggered the Entire Ambush It starts with a…

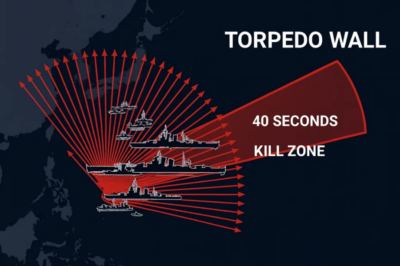

CH2. The 40-Second Torpedo Wall — How 22 Shots Erased Japan’s Night-Fighting Advantage

The 40-Second Torpedo Wall — How 22 Shots Erased Japan’s Night-Fighting Advantage The date was August 6th, 1943. The place:…

CH2. What Eisenhower Said To His Staff When Patton Crossed the Rhine Without Orders!

What Eisenhower Said To His Staff When Patton Crossed the Rhine Without Orders! March 22nd, 1945, was supposed to be…

CH2. Why Japanese Admirals Stopped Underestimating American Sailors After Midway

Why Japanese Admirals Stopped Underestimating American Sailors After Midway Commander Joseph Rochefort had forgotten what it felt like to be…

CH2. How One Sniper’s “STUPID” Mirror Trick Outsmarted the Germans Snipers

How One Sniper’s “STUPID” Mirror Trick Outsmarted the German Snipers November 3, 1944 Metz, France The wind off the Moselle…

End of content

No more pages to load