Why Japanese Admirals Stopped Underestimating American Sailors After Midway

Commander Joseph Rochefort had forgotten what it felt like to be tired.

He knew, in an abstract way, that his body ached. That the skin around his eyes felt raw from the rasp of his knuckles when he rubbed them. That his hands shook from too much coffee and not enough food. But those details belonged to some other life, some other man.

Right now, there was only the map.

The basement of the 14th Naval District headquarters at Pearl Harbor hummed with machines and murmuring voices. The air was cold to protect the precious IBM tabulators. Men in wrinkled uniforms moved between racks of radios and stacks of message blanks. Cigarette smoke coiled under a ceiling that felt too low for the weight of the war pressing down on it.

Rochefort stood in his worn carpet slippers and red smoking jacket, staring at a vast chart of the Pacific. Colored pins marked American ships. String traced suspected Japanese courses. Midway, a dot in a sea of blue, sat like a baited hook.

It was June 4th, 1942, 9:47 in the morning.

In roughly ninety minutes, one of two things would happen.

American dive bombers would find the Japanese carrier fleet.

Or they wouldn’t.

If they found it, the United States might change the course of the war. If they did not, Japan would command the Pacific for the next decade. Every calculation, every intercepted message, every sleepless night spent wrestling with the Japanese naval code JN-25B had led to this narrow window of time, this wedge of possibility.

Rochefort’s fingers curled against his palms. Somewhere out there, beyond that map and its pins and strings, young men in aircraft he had never seen were flying over empty water, guided by numbers and words dragged out of an enemy language and an enemy mind. He had done everything he could. Now it was on them.

He wondered, not for the first time, if they knew how much the Japanese had underestimated them.

He doubted it.

Sailors didn’t read enemy war plans. They didn’t sit in rooms full of deciphered arrogance.

But he did. And that was why his exhaustion meant nothing.

He had work to finish.

— — —

The first American to die from Japanese contempt for American resolve had never heard of JN-25B.

He was 26 years old, freckled, with a Midwestern face that looked younger than his rank. First Lieutenant George Ham Cannon, United States Marine Corps, commanded Battery H on Sand Island, Midway Atoll.

On the night of December 7th, 1941—about fourteen hours after Japanese torpedo planes tore Pearl Harbor open—two Japanese destroyers slid through the darkness toward Midway. Sazanami and Ushio cut across the waves without air cover, without battleship support, without reconnaissance.

They didn’t think they needed any of that.

Americans were soft, Japanese officers said. Americans were predictable. Americans were slow to react and quick to panic.

So the destroyers came in casually, as if knocking on the door of an empty house.

At 21:31 local time, the first shells landed.

The command post of Battery H shuddered. A shell slammed through sand and timber, exploding inside the small bunker where Cannon stood with his men. The blast tore his left leg apart below the knee. Shrapnel drove through his abdomen and chest. The world turned white, then red, then narrow.

“Lieutenant, we’ve got to get you out!” one of his Marines shouted, grabbing for him.

“Stay at your gun,” Cannon rasped, voice ragged, shock already clawing at him. “I’m not going anywhere.”

They tried anyway, but he ordered them back to their stations. Blood soaked the concrete floor beneath him. The pain came in sharp waves, then dulled, then returned with sickening clarity. The roar of Japanese guns outside grew louder, then faded, then pounded again as the destroyers shifted fire.

Cannon propped himself up against a wall, gritted his teeth, and kept commanding his battery.

“Number three gun, adjust fire! Walk it up their stern!”

His men, seeing their shattered commander still giving orders, fought harder.

Shells from Battery H found their mark. Sazanami staggered under the impacts. Ushio’s superstructure flashed and burst. Outgunned and surprised by the ferocity of the defense, both destroyers withdrew earlier than planned.

Only when the firing slackened did the corpsmen push their way to Cannon.

He was unconscious by then, his uniform dark and sticky. He died shortly after midnight.

The official citation later said he had died heroically defending Midway. It did not mention the casual swagger with which those destroyers had approached, the lazy confidence that American defenses would crumble.

Their error had cost them time, metal, and men.

But Cannon was still dead.

That would be the pattern for six months. Japanese underestimation would never quite stop them in those early days—but it would start to cost them more than they understood.

— — —

In Tokyo, in smoke-filled rooms lined with maps and calligraphy, admirals talked about Americans like they were something less than serious adversaries.

They had their reasons.

Hong Kong fell in eighteen days.

Singapore—invincible fortress, the pride of the British Empire—collapsed in seventy days.

The Philippines, after months of fighting, finally surrendered. Manila fell. Bataan fell. Corregidor fell.

On every map, the Imperial colors spread outward like a rising tide.

In war college lectures and wardroom conversations, American sailors were dismissed as soft, undisciplined, unfocused. The attack on Pearl Harbor was held up as proof: American battleships caught napping at anchor, aircraft lined up neatly on runways, no serious expectation of danger.

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto should have known better.

He had lived among Americans, studied at Harvard, played poker in smoky back rooms, traveled their railroads, seen their factories clawing at the sky. He knew better than most Japanese officers what that industrial power could do if roused.

But even he, in time, began to speak of American naval officers with a trace of disdain. Less professional. Less dedicated. Too fond of comfort. Too wedded to routine.

So when he designed the attack on Pearl Harbor, he assumed the American carriers would be in port—just as American schedules said they should be.

And when he conceived the Midway operation, he assumed American responses would be slow and conventional—just as they had been before.

He spread his forces across millions of square miles of ocean, confident that no American intelligence service could track them, that no American mind could piece the threads together in time.

In Tokyo, men nodded over documents written in precise brush strokes.

In Hawaii, underground, in a cold basement full of humming machines, a man in a red smoking jacket quietly proved them wrong.

— — —

Joseph Rochefort was not what most people imagined when they thought of a naval officer. He was not tall and imposing. He did not delight in formal dinners or spotless uniforms.

He liked comfortable shoes, strong coffee, and difficult problems.

Born in Dayton, Ohio in 1900, he had left high school early to enlist in the Navy during the First World War. The Navy, short of officers during the conflict, put him through a wartime training program and handed him a commission. Somewhere along the way, someone noticed that he was exceptionally good at languages, puzzles, and patterns.

They sent him to Japan.

For three years he walked streets filled with kanji signs, listened to conversations in tea houses, and struggled through formal texts and offhand slang. He returned to Japan in the early 1930s for advanced studies, carrying with him an increasingly nuanced sense of how the Japanese Navy thought, wrote, and coded.

By 1941, Rochefort was one of perhaps a dozen American officers whose skill sets overlapped in a very dangerous way for Japan: fluent Japanese, a deep feel for Japanese culture, and serious cryptanalytic experience.

The Navy parked him in Pearl Harbor’s basement, in a unit with an innocuous name: Station HYPO.

There, in rooms cold enough to make the unprepared shiver, a strange collection of men gathered: reservists and enlisted sailors, linguists and radiomen, clerks and mathematicians. Some had been musicians in the battleship California’s band. Rochefort had recruited them deliberately, believing that the ability to read sheet music—notes and spaces and rhythms—would carry over to seeing patterns in clouds of numbers.

He was right.

But even genius could not turn JN-25B into an open book overnight. The Japanese naval code system used five-digit groups, each representing a word or phrase, then further scrambled them with additive tables that changed periodically. It was language buried in math buried in culture.

Before Pearl Harbor, Station HYPO could read maybe ten or fifteen percent of the traffic. Enough to know something was happening. Not enough to know exactly what.

Then December 7th came, and smoke rose over Battleship Row, and everything changed.

The war was no longer theoretical. It was no longer an exercise in professional pride. It became personal. It became desperate.

HYPO went to war.

They slept in shifts. Ate at their desks. Lived by the clacking rhythm of typewriters and the grinding churn of IBM machines. Rochefort padded through the narrow corridors of his underground kingdom in that ridiculous red jacket and worn slippers, his appearance prompting snickers from some officers and raised eyebrows from others.

Washington didn’t like him much. He was too blunt, too willing to tell senior officers when they were wrong, too uninterested in ceremony.

He didn’t care.

Every message he helped break might be one less torpedo striking an American hull. One less sailor slipping beneath black water.

By April 1942, HYPO could read roughly forty percent of Japanese naval traffic—not the whole text, not yet, but enough. Enough to pull out threads, see patterns, recognize build-ups and preparations. Enough to sense something gathering far out at sea.

The Japanese called it an operation against “AF.”

AF, according to their map grid, was a place.

What place, exactly, was the question.

In the cool air of HYPO’s basement, Rochefort frowned at the cluster of references to AF—fuel loads, landing forces, air base construction units. This was no small raid. It smelled like an invasion.

He laid out every intercepted mention of AF, every weather report, every reference to aircraft ranges and supply schedules. When he looked at the pattern, the answer seemed obvious.

AF was Midway.

Previous intercepts had used A-designations for central Pacific locations. A weather report for AF matched known conditions at Midway. References to landing forces and construction units suggested an island that was both militarily useful and lightly defended.

Midway fit perfectly.

But in Washington, men who had never walked through the chilled air of HYPO’s basement saw things differently.

Captain John Redman, head of the Navy’s code and signals section in D.C., distrusted Rochefort. Disliked him, even. He had his own analysts, his own theories. AF, he insisted, might be the Aleutians. Might be Port Moresby. Might even be the American west coast.

Others chimed in with their own guesses. Alaska. Hawaii. Somewhere in the South Pacific.

Admiral Ernest J. King, Commander in Chief of the United States Navy, listened to the differing voices and felt, perhaps for the first time in his career, the limits of command authority.

He couldn’t order the enemy to be predictable.

He had to choose which intelligence officer was right.

And the price of choosing incorrectly might be the war.

— — —

The decision would ultimately belong to Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet.

Nimitz understood maps the way a surgeon understands anatomy: not as abstractions, but as living systems where pressure in one place caused pain in another. For months he had watched the Japanese advance—Hong Kong, the Philippines, Singapore—like a cancer spreading along arteries of sea lanes and islands.

He knew he had three operational carriers: Enterprise, Hornet, and the battered Yorktown. The Japanese, by contrast, had at least four heavy carriers and probably more.

If he guessed wrong about AF, he could lose everything.

If AF was Midway and he sent his carriers somewhere else, the outpost would fall and Japan would gain an unbeatable forward base.

If AF was not Midway and he concentrated there, he would leave the actual target exposed and present his carriers for destruction in the wrong ocean.

He sat in his office at Pearl Harbor, looking at the same Pacific expanse Rochefort studied from below—but where Rochefort’s map was covered in pins and strings, Nimitz’s map was covered in responsibility.

Rochefort knew AF was Midway. He felt it in the pattern of intercepted texts and in the rhythm of Japanese logistics. But feeling wasn’t enough.

So he decided to make the Japanese prove it.

He walked into Lieutenant Commander Edwin Layton’s office on May 19th, 1942, carrying a sheaf of decrypts and the weight of a wild idea. Layton, Nimitz’s intelligence officer, had studied in Japan with him. They had wrestled with kanji together, sweated through exams, shared late-night conversations in smoky Yokohama cafes.

Now they shared something else: a desperate need for certainty.

“We’re going to make them tell us,” Rochefort said quietly.

He explained.

Midway, he proposed, would broadcast an unencrypted message reporting a breakdown in its water distillation system. In plain English. No codes. No fancy tricks. Just a mundane complaint from a small island garrison: the desalination plant is down; we’re short on fresh water; we need resupply.

Japanese radio stations in the Marshalls would almost certainly intercept it. Believing their JN-25B code unbreakable, they would then report to Combined Fleet headquarters that “AF” was low on water and recommend that any invasion force bring additional equipment.

If HYPO intercepted and broke that Japanese message—and if it mentioned AF being short of water—then the answer would be undeniable.

AF was Midway.

The plan was simple and brilliant. It was also dangerous.

If the Japanese smelled a trap, they might change their entire code system. HYPO’s window into their plans would slam shut. Months of grinding progress would vanish.

If the ruse failed to bait a Japanese response, they would be no closer to certainty.

If Washington still refused to believe them even with such proof, then nothing would matter.

But doing nothing felt worse.

Layton listened, face still, eyes thoughtful. Then he carried the idea upstairs to Nimitz.

Nimitz heard them out in silence. Then he nodded once.

“Do it.”

The orders went out via secure submarine cable to Midway on May 20th. The garrison’s radiomen received them with raised eyebrows. They were used to encoding everything. Encryption had become habit. Now they were being told to shout their troubles into the ether.

On May 22nd, the message went out.

WATER DISTILLATION PLANT OUT OF ACTION STOP FRESH WATER SUPPLY GOOD FOR APPROX TWO WEEKS STOP REQUEST RESUPPLY EARLIEST POSSIBLE DATE STOP

The words flew through the sky as radio waves, crossed hundreds of miles of ocean, brushed past islands and ships and static.

Japanese radio operators in the Marshall Islands caught them.

“An American outpost is short of water,” they reported, casting their own message into the air. This one was wrapped in the intricate armor of JN-25B. To them, it was unbreakable.

To HYPO, it was a locked door that already had cracks around the hinges.

Within forty-eight hours, Rochefort’s people were hunched over tables, comparing groups of numbers to previously broken codebooks, testing additives, looking for familiar patterns.

When the message finally resolved itself into Japanese text on the page, Rochefort felt his throat tighten.

Aerial reconnaissance has confirmed that AF is an objective. AF reports a shortage of fresh water. Recommend invasion force carry additional desalination equipment.

AF. Short of water.

Midway.

He took the decrypt upstairs, each step on the stairwell carrying with it months of strain and the thudding pulse of what-if. He laid the sheet on Nimitz’s desk.

“This is it, Admiral.”

Nimitz read it once. Twice. He did not smile. His face did not relax. But some tension in his shoulders seemed to shift, as if a load had been redistributed from uncertainty to action.

“All right,” he said. “We know where they’re coming. Now we decide what to do with it.”

Somewhere out in the fleet, men hammered bent steel back into shape.

— — —

The carrier Yorktown looked like a ghost when she limped into Pearl Harbor after the Battle of the Coral Sea.

Three bombing hits had punched through her flight deck. Fire had scorched equipment, wiring, paint, and flesh. Her steering had been damaged. Her pumps had groaned just to keep her afloat.

The engineers who came aboard to assess her shook their heads. Ninety days, they said. Maybe more. She needed to go back to the West Coast. Maybe farther.

Nimitz listened. Then he quietly told them they had seventy-two hours.

It wasn’t a suggestion.

Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard erupted into motion. The word spread across workshops and barracks like a shockwave. Carpenters, welders, electricians, pipefitters, riggers—over 1,400 men swarmed toward the mutilated carrier like white blood cells toward an open wound.

They worked in continuous shifts. Night meant nothing. The sun sank and the floodlights snapped on. Torches flared blue and white in the dark. Hammers rang against steel. Sparks fell like meteors into the harbor.

Teams cut away twisted metal from the flight deck and replaced it with new steel plates, barely cooled from the mills that had birthed them. Electricians snaked wires through spaces still reeking of smoke. Painters chased rust with frantic strokes. Damage control crews patched hull breaches with hurried skill.

Onboard, sailors stepped around repairmen, carrying ammunition, food, spare parts. The ship’s own crew joined the labor where they could, lending hands to patch their wounded home.

They were not just fixing a ship.

They were buying a chance.

When Yorktown sailed again on May 30th, some repair crews were still aboard, finishing work amid the rolling of the sea. She joined Enterprise and Hornet at a rendezvous point 325 miles northeast of Midway, a location named with dark humor and cautious hope: Point Luck.

There, Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher and Admiral Raymond Spruance gathered their thin strength: three carriers, eight cruisers, fifteen destroyers, and 233 aircraft.

They were outnumbered. Outgunned.

But they had something the Japanese didn’t.

They knew what was coming.

— — —

On June 3rd, a PBY Catalina went hunting.

The big patrol bomber, with its long wings and boat-shaped hull, droned out over the endless Pacific, crew members scanning the water for ships, their eyes gritty from long patrols.

At 9:04 in the morning, one of them leaned forward sharply.

“Ships. Bearing…”

In the distance, gray dots marred the clean sweep of blue. Magnified through binoculars, they became hulls, wakes, superstructures. Transports. Escorts. Heading northeast.

The crew sent a contact report. Midway acknowledged. Fletcher’s task force received it soon after.

It was the Japanese invasion force, just where Rochefort’s estimates said it would be.

But the carriers were not with them.

They would come from another direction, like a second knife following the first.

Fletcher let the invasion convoy be. His hunters were waiting for bigger prey.

The morning of June 4th began with radar screens and rising tension.

At 5:53, Midway’s radar picked up incoming aircraft a hundred miles out. Dozens of returns, a dense swarm.

By 6:00, another PBY found the Japanese carrier force, reporting their position, course, and speed.

That report reached Fletcher as Japanese planes hurtled toward Midway.

“Launch everything,” he ordered.

On Enterprise, Hornet, and Yorktown, decks roared to life. Steel catwalks trembled under running feet. Chocks clattered away from landing gear. Engines coughed, then roared, propellers blurring into spinning circles.

Pilots climbed into cockpits slick with sweat and nervousness, some of them barely older than twenty. Aviation machinist mates slammed canopies shut. Signal officers waved flags.

There was no time for the neat choreography American doctrine preferred: dive bombers, torpedo planes, and fighters launching as coordinated groups with carefully sequenced rendezvous in the sky.

Instead, waves went out like frantic punches: torpedo bombers first, creeping low and slow; fighters struggling to catch up; dive bombers following their own paths toward predicted intercept points.

Chaos, riding the wind.

At 6:30, Japanese bombs fell on Midway.

The atoll shook. Fuel tanks erupted in sheets of fire. The seaplane hangar blew apart. The powerhouse shuddered under impacts.

Marine fighters—obsolete Brewster Buffaloes and a handful of Grumman Wildcats—scrambled into the attack, climbing into the swarm. They were outnumbered, outflown, and outgunned by Japanese Zeros. Fifteen of twenty-six fighters were shot down. Many that survived limped back riddled with holes, their pilots bleeding and out of ammunition.

Midway burned, but not enough. The runway remained usable. The island still had teeth.

And more importantly, the Japanese had revealed themselves.

Now it was a question of whether the men launched from Point Luck could find them.

— — —

Lieutenant Commander Clarence Wade McClusky Jr. had never been the sort of man to quit easily.

He had grown up in Buffalo, New York, learned to fly Navy planes when the world still thought of aircraft carriers as experiments. Now he stood in the cockpit of an SBD Dauntless dive bomber, the canopy framing a sky so bright it hurt his eyes.

Below him, the Pacific stretched out like forever.

His orders were simple in theory and brutal in practice.

Find the Japanese carriers.

Kill them.

He led thirty-three Dauntlesses—bombing squadron 6 and scouting squadron 6, plus himself as air group commander—into the morning sky. His chart, strapped to his thigh, showed the last reported position of the Japanese carriers, along with course and speed.

He drew a line on that chart, calculated where the carriers should be now. He set his compass, watched the ocean roll beneath him, heard the steady thrum of his engine.

At 9:20, he reached the point his pencil had predicted.

The horizon mocked him.

There was nothing.

No carriers. No destroyers. No smudges of smoke. Just ocean.

He checked the numbers again. Maybe the PBY’s report had a bearing error. Maybe the wind had shifted. Maybe his own navigation had drifted. Maybe the Japanese had changed course.

Fuel gauges told their own story. The Dauntless was a sturdy aircraft, but it could not fly on wishful thinking. Some of his pilots had already diverted, turning back toward the comforting, invisible presence of Enterprise somewhere behind them.

McClusky thought about the torpedo squadrons that had gone in earlier.

Torpedo Squadron 8 from Hornet had never been seen again. Every plane shot down. Only one man, Ensign George Gay, would live to float amid wreckage and witness the rest of the battle.

Others from Midway itself had attacked: Marine torpedo bombers, Army B-26 bombers, B-17s dropping bombs like pebbles from too high up. Again and again, American pilots had driven straight into Japanese fighter screens and anti-aircraft fire. Again and again, they had failed to land a hit.

Their sacrifice, as of 9:20 in the morning, had bought nothing tangible.

If McClusky turned back now, if his dive bombers returned to their carriers without having even sighted the enemy, then all those dead men would have died into an empty sea.

He felt something tighten in his chest.

“Fifteen more minutes,” he told himself, glancing at his wristwatch. “We will search fifteen minutes more.”

He pushed his formation on, scanning the water for any sign—a smudge of smoke, a faint wake, a glint of steel.

Still nothing.

He forced himself to think, not just feel.

The Japanese carriers were fast, but they were not ghosts. They had been attacked again and again throughout the morning. Every time they dodged torpedoes or bombs, they turned hard. Every evasive maneuver stole speed from their advance toward Midway.

If they had passed his intercept point already and were now south of his position, then the PBYs from Midway, sweeping that sector, should have seen them. No such reports had come in.

That meant, logically, that the enemy had not slipped past to the south. They were somewhere else.

If not there, then where?

North.

He looked at the sky, as if the answer might be written there. Then he made his choice.

He would turn north in a box search pattern, widening his arc. It would burn more fuel. It would push some of his planes past the safe line of no return.

But it might find the enemy.

He banked his Dauntless. The formation followed, thirty-one aircraft holding tight, their propellers refracting sunlight into invisible blades.

Minutes later, one of his pilots called out, voice crackling over the radio.

“Destroyer! Dead ahead, high speed!”

Through his canopy, McClusky saw it: a small shape knifing through the water at full power, froth boiling along its hull.

The destroyer Arashi.

It had stayed behind to depth-charge the American submarine Nautilus, hammering the submerged intruder with explosives so powerful they rattled teeth miles away. Now, task done, it raced to rejoin the carrier task force as quickly as its engines would allow.

Ships did not sprint aimlessly.

If Arashi was charging northeast, then something valuable lay along that line.

McClusky felt a surge of certainty so sudden it almost made him dizzy.

“Follow that destroyer,” he ordered.

The Dauntlesses swept in a great arc behind Arashi, climbing higher, higher, until they rode at 19,000 feet. The air thinned and grew colder. Below them, the destroyer became a darting fleck of white wake and gray hull.

At 10:15, the horizon changed.

Thin white scratches appeared on the blue surface—a pattern of wakes, wide and angled, the signature of heavy ships running at speed, turning slightly as they held formation.

Then the ships themselves rose into view.

Four carriers.

Eight escorts.

Dozens of dots on the decks that McClusky knew were aircraft, fueled and armed, crowded together like tinder piled for a single spark.

He exhaled slowly.

This was it.

“Attack.”

— — —

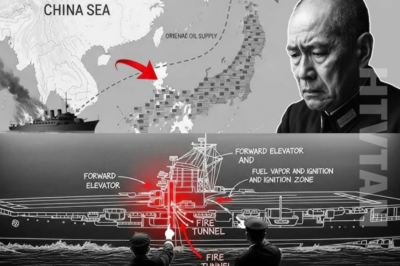

From above, the Japanese carriers looked like vast, flat blades slicing through the sea: Kaga and Akagi closest, Soryu and Hiryu farther away.

On Kaga’s deck, sailors in colored shirts hurried between aircraft. Fuel lines snaked like veins. Bombs and torpedoes sat on carts, ready to be hoisted into place. Ordinaries were doing ordinary things—smoking, shouting across the din, glancing up at the clear sky and thinking of nothing in particular.

They had spent the morning dodging death with derisive ease. American torpedo planes had come at them like doomed insects, slow and clumsy. Japanese Zero pilots had taken them apart ruthlessly, bragging over the radio, their kill tallies growing with every pass.

They were winning.

Then the sirens began to howl.

An observer on a destroyer, eyes trained upward as a matter of habit, saw tiny specks glittering in the sun above them. Others picked them out, noticed the telltale brightness of diving planes.

“Enemy dive bombers, high!”

On Enterprise’s Dauntlesses, pilots shoved their throttles forward and tipped their noses over. The world swung upward. Gravity reached up and grabbed them by the spine.

McClusky’s formation split, both squadrons angling toward Kaga and Akagi. According to doctrine—carefully drilled but difficult to execute in the chaos of war—different squadrons were supposed to take different carriers to spread the blows.

But dive bombing, from that altitude, with anti-aircraft fire blossoming all around and fighters clawing up from below, was not a doctrinal exercise. It was a plunge from sky to sea, guided by instinct and training fighting against the primal urge to pull away.

As both squadrons converged on Kaga, one man realized the error.

Lieutenant Richard Halsey Best, commanding bombing squadron 6, had already tipped into his dive when his brain registered that every plane around him was pointed at the same target.

If they all hit Kaga, the other carriers would escape.

He did not have time for a meeting, a conference, or a long debate. He had seconds.

He yanked his Dauntless out of its dive, hauling against the crushing force that tried to glue him into his seat. His wingmen saw his flash of motion and followed, their own aircraft shuddering as they reversed. He pointed his nose at Akagi instead.

Below, Kaga filled the sights of the rest of the formation.

At 10:22, the first 1,000-pound bomb fell.

Gravity pulled it down, faster and faster, a steel cylinder cutting the air with unfeeling precision. It slammed through Kaga’s wooden flight deck just forward of the midships elevator, punched through into the hangar deck, and exploded in a confined, crowded space.

Men and machines vanished in an instant of incandescent force.

The blast ripped fuel lines and tore open bomb casings. Gasoline turned to vapor in the heat and ignited with a roar. Flames leapt from plane to plane, touching off more explosions.

Seconds later, more bombs struck—one amidships, one near the stern. Each impact shattered structure, ruptured pipes, smashed bulkheads. Fire became a living thing, rushing along passages, sucking oxygen out of rooms, collapsing steel as it heated and buckled.

On Akagi, sailors saw Kaga wreathed in smoke and fire. Some stared, mouths open, unable to understand how a ship so mighty could be wounded so completely in the space of breaths.

Then their own world exploded.

Best’s Dauntless screamed downward at four hundred miles an hour. Very small corrections in his control inputs nudged the sight over the target point: just aft of the middle elevator. He held the dive until his altimeter spun toward 1,500 feet, then thumbed the bomb release and pulled back with everything he had.

Behind him, his rear gunner cursed and whooped all at once.

The bomb sliced into Akagi’s deck almost exactly where he had aimed and punched its way into the hangar deck. It detonated among readied aircraft and fuel and munitions.

Fire blasted upward through the elevator well, flinging debris high into the sky.

One of Best’s wingmen scored a near miss that tore into Akagi’s hull and damaged her rudder. The proud carrier began to spin in circles, no longer under control.

Japanese damage control parties dashed toward the flames with hoses and extinguishers, but the inferno consumed them. Aviation gasoline burned hotter than imagination. Ammunition cooked off in thunderous bursts.

Men screamed amid the roar of the fire.

On the other side of the formation, dauntless dive bombers from Yorktown, led by Lieutenant Commander Max Leslie, found Soryu. They came down in tight, textbook dives, bombs falling with geometric precision.

Three hits.

Three more eruptions in hangars crammed with fuel and ordnance.

Soryu staggered under the blows, flames tearing through her insides.

In less than five minutes—from 10:22 to roughly 10:26—the Japanese Navy lost three of the four carriers that had hammered Pearl Harbor six months earlier.

On the light cruiser Nagara, Admiral Chuichi Nagumo watched the sky and saw his war crack apart.

For half a year, his carriers had been avenging samurai, striking with apparent invincibility. They had smashed battleships at Pearl Harbor. They had raided Darwin, Ceylon, the Indian Ocean. They had felt untouchable.

Now, Kaga burned like a funeral pyre. Akagi’s deck was torn open. Soryu vomited smoke and flame into the sky.

It had happened too fast. It made no sense.

American torpedo planes, all morning, had been useless, slaughtered by his combat air patrols. Their tactics had been crude, their aircraft obsolete, their attacks suicidal.

Now American dive bombers had arrived out of a clear sky, at exactly the wrong moment.

How had they found his carriers so precisely?

How had they coordinated their approach?

How had they slipped past his scouts and pickets and radar-less watch?

Nagumo did not know. He had never heard of Station HYPO. He did not know Joseph Rochefort existed.

He assumed it was luck.

It was not.

— — —

The fourth carrier, Hiryu, refused to die so easily.

While Akagi, Kaga, and Soryu burned, Hiryu kept enough planes ready to launch two counterstrikes against Yorktown. Her pilots flew with the same deadly skill that had terrorized the Pacific for months.

They found Yorktown and came at her in screaming dives, bombs and torpedoes falling with surgical cruelty.

Explosions ripped through the American carrier. Fires roared across her decks. The ship shuddered, slowed, listed, then steadied as damage control teams swarmed.

When the smoke cleared, she was wounded but alive.

Hiryu’s aircraft came again. More hits. More fire. Yorktown groaned as she lost power, her crew fighting the ship back from the edge of death.

By late afternoon, Enterprise’s dive bombers found Hiryu.

They came in as the sun slanted west, their shadows stretching ahead of them. Bombs fell in a final, decisive cascade.

Hiryu staggered under the impacts, her own hangar deck joining the inferno that had claimed her sisters. By nightfall, she too was doomed.

Four carriers gone.

An entire striking arm of the Imperial Japanese Navy—men who had trained together for years, flown together, lived together—scattered into the sea.

For Japan, the numbers told one story: four carriers, one heavy cruiser, 248 aircraft, over 3,000 men lost—many of them irreplaceable veterans.

For the United States, the toll was painful but different: one carrier ultimately lost—Yorktown—one destroyer, around 150 aircraft, and just over 300 men killed.

The ratio, roughly ten to one, was shocking.

But statistics could not capture what changed in the minds of the men who read the reports.

— — —

Admiral Yamamoto received the news aboard his flagship, Yamato, 600 miles west of the carrier battle.

Reports came in fragmented at first—an attack, fires, damage. Then more clear: Akagi crippled. Kaga burning uncontrollably. Soryu abandoned. Hiryu hit.

It didn’t fit anything he understood about his enemy.

He had built the Midway operation on the assumption that American intelligence would be a step behind, that American reactions would be slow, that their carriers would stumble into his trap instead of waiting with one of their own.

Now, instead of American ships blundering forward, it was his own carriers that had sailed into a crosshair he hadn’t seen.

He tried to rescue something from the wreckage. He ordered battleships forward, hoping for a night engagement where Japanese training in night fighting and gunnery might restore the initiative. He redirected forces from the Aleutians operation.

But the American carriers refused to cooperate.

They withdrew to the east, staying outside the range of his guns. Their pilots had done their work. Their admirals would not risk it in a kind of battle that favored Japanese strength.

By midnight on June 5th, Yamamoto faced the unthinkable.

The operation had failed.

He ordered a general retreat.

Later, in quiet moments dictated to his staff or recorded in private diaries by officers like Admiral Matome Ugaki, the explanations would begin: blame placed on insufficient reconnaissance, on Nagumo’s hesitations, on the unfortunate timing of relaunching aircraft.

In the days immediately after the battle, many clung to the idea that better scouting, quicker decision-making, or different luck might have saved the day.

But as more reports trickled in—after-action accounts from surviving pilots, intercepted American broadcasts, fragmentary intelligence—a darker realization took shape.

The Americans had known.

Not guessed. Not blundered. Known.

They had been waiting in exactly the right quadrant of ocean. They had launched at exactly the right time. They had arrived over the Japanese carriers at the precise moment when their decks were crowded with aircraft, their hangar decks packed with fuel and munitions.

This was not the work of a backward enemy, stumbling into conflict.

This was the work of a foe who understood them far better than they had imagined.

— — —

In the weeks and months after Midway, Japanese survivors were ordered not to speak of the battle.

Those who made it back to Japan were quarantined, kept away from the public, their stories folded into classified reports. Official casualty figures downplayed the losses. Newspapers spoke vaguely of a “naval engagement near Midway” without mentioning the names of lost carriers.

The Japanese people would not learn the full truth until after the war.

But inside the corridors of power, a quiet revolution began.

On June 15th, 1942, while the wrecks of Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu still lay beneath the waves, Vice Admiral Nagumo’s staff started drafting new doctrine for carrier warfare. The resulting manual, issued in late July, contained a statement that would have seemed like heresy a year earlier:

Carriers were the decisive weapons of modern war at sea.

Battleships would support them—not the other way around.

For decades, Japanese naval theory had orbited around the concept of the decisive fleet engagement: long lines of battleships trading salvos until one side broke. Carriers were tools to weaken the enemy before the climactic exchange of gunfire.

Midway shattered that vision.

No battleship had fired a shot there. Yet an entire arm of the Japanese Navy had vanished.

Doctrine began to shift.

But some habits proved harder to kill than carriers.

Japanese planners had favored dispersing their forces across wide stretches of ocean, believing that multiple groups moving separately would confuse American intelligence and allow rapid concentration once the enemy was found.

At Midway, that dispersion meant that Yamamoto’s battleships and supporting cruisers were too far away to matter when the carriers came under attack. When help might have counted, it was out of reach.

Yet old beliefs died slowly.

In battles months later—the Eastern Solomons in August 1942, Santa Cruz in October—Japanese forces would still be split into scattered groups, arriving piecemeal instead of as a single hammer blow.

The tactical changes that truly mattered, in the end, were not in formation diagrams but in attitudes toward the enemy.

Before Midway, Japanese air crews were taught that Americans were inferior pilots flying inferior machines. That their tactics were slow, unimaginative, and clumsy.

After Midway, those lectures grew strained, then stopped.

Pilot reports from the battle spoke of American dive bombers pressing attacks through dense anti-aircraft fire, ignoring Zeros looming around them. Their hit rates, around fifteen percent, were three times peacetime expectations. Their coordination, despite chaotic launches, had been good enough to deliver simultaneous attacks from multiple directions.

American courage, skill, and adaptability were no longer theoretical. Japanese airmen had watched their bombs fall. They had seen their ships burn.

— — —

The strategic tide turned slowly but relentlessly.

On August 7th, 1942, American Marines waded ashore on a place few Americans had heard of before: Guadalcanal.

It was the first major American offensive of the Pacific war. A small island in the Solomons, its airfield—the unfinished Lunga Point strip, later renamed Henderson Field—offered control over critical shipping lanes.

For Japanese commanders, the landing was an insult, a provocation, and an opportunity. They believed they could throw the Americans back into the sea with a few well-timed blows. After all, they had been doing exactly that to Allied forces for months.

But Guadalcanal turned out to be a grinding, six-month nightmare for both sides.

On nights bloodied by shellfire, Japanese destroyers slipped down “The Slot,” unloading men and supplies under cover of darkness—the “Tokyo Express.” American cruisers and destroyers fought them again and again in brutal close-quarters battles, searchlights stabbing across the water, shells smashing into superstructures, torpedoes punching unexpected holes into hulls.

Carriers clashed again: the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, the Battle of Cape Esperance, the Battle of Santa Cruz. One by one, Japanese ships that had seemed untouchable in 1941 vanished beneath the waves.

In one after-action report in late 1942, Japanese intelligence officers noted with unease that the torpedo bombers they now faced over the Solomons were not the same slow Devastators they had massacred at Midway.

They were Grumman TBF Avengers.

Faster. Better armored. More heavily armed.

The Americans were changing.

By October 1942, Japanese naval intelligence had circulated assessments warning carrier commanders not to underestimate American pilots. Training levels, the reports said, appeared equal to Japanese standards. Carrier operations showed sophisticated coordination and improved fighter direction.

The reports recommended thicker combat air patrols, better radar use, more aggressive damage control procedures.

But recommendations could not conjure new ships or trained men from thin air.

American industry, once awakened, hummed with an energy that Yamamoto had feared and others had dismissed. New carriers slid out of dry docks. Hundreds of aircraft rolled off assembly lines each month. Pilot training programs expanded.

Japan’s industrial base—smaller, starved of resources by blockades and geography—could not keep pace.

The imbalance that Yamamoto had tried to offset with surprise and superior training now grew every month.

Midway had not ended the war. Far from it. There were still years of brutal fighting ahead: Tarawa, Saipan, Leyte, Iwo Jima, Okinawa.

But Midway had broken something at the top of the Imperial Japanese Navy: their certainty.

From that moment onward, Japanese admirals planned knowing, at last, that the men they faced were not soft.

— — —

In early 1943, the Pacific war entered a strange phase.

The Japanese Navy, battered and bleeding from the Solomons campaign, sought ways to lift morale. The Americans pressed harder with each passing month.

Admiral Yamamoto decided to visit forward bases in the Solomons area, to show the men at the front that their commander understood their hardships, to stand beside them amid muddy airfields and sweltering jungle heat.

His itinerary was transmitted by radio: departure time from Rabaul, arrival time at Bougainville, aircraft type, the number of escort fighters, the exact route.

JN-25B wrapped the message in the same mathematical armor that had failed at Midway. Japanese staff officers, still not fully aware of the depth of America’s cryptanalytic progress, believed it was secure.

In a different basement now, in a different set of rooms warmed by different machines, successor cryptanalysts to Rochefort—who had already been quietly pushed aside for his troublesome independence—intercepted that message and set to work.

When the code gave way and the text emerged, the significance was obvious.

The Americans had a chance to kill the architect of Pearl Harbor and Midway, the one Japanese admiral who truly grasped both their nation’s potential and its limits.

The intelligence went up the chain, until it lay once more on Nimitz’s desk.

He knew the stakes.

If they struck at Yamamoto, the Japanese might realize their code had been compromised and overhaul their entire cryptographic system. HYPO and its sister stations would lose their vantage point.

But if they did nothing, the man whose vision had nearly destroyed the Pacific Fleet would live to guide Japan’s war for months, maybe years more.

The calculation was grim.

In the end, Nimitz authorized the mission.

On April 18th, 1943, sixteen P-38 Lightning fighters took off from Guadalcanal’s Kukum Field on an extremely long-range mission, their tanks filled to the brim, their pilots briefed down to the minute. They flew a circuitous route to mask their origin and to be at exactly the right point in the sky at exactly the right time.

They arrived over Bougainville minutes ahead of Yamamoto’s plane.

When the Japanese transport appeared, flanked by Zero escorts, the American fighters pounced.

The engagement was short and savage. Tracer rounds stitched the air. Engines screamed. The transport took hits, smoked, dipped its nose, and plunged into the jungle below.

Yamamoto died in the wreckage, the war he had both warned against and helped wage suddenly no longer his to shape.

The message had been decrypted. The strike had been launched. The result was exactly what the Americans had intended.

The Japanese, incredibly, still did not fully grasp how deeply their codes had been penetrated.

But their admirals, those who sat in planning rooms afterward, felt once again the same chill that had descended after Midway.

Somewhere out there, in some enemy basement, men were listening.

— — —

Joseph Rochefort did not receive a hero’s welcome for his part in Midway.

He did not receive much of anything.

His direct line to Nimitz had angered Captain John Redman and others in Washington. They saw in Rochefort’s success not a vindication of field intelligence, but a threat to their authority.

He was, they said, insubordinate. Too independent. Too willing to bypass channels.

In late October 1942, his orders came. He was being transferred away from Station HYPO.

No new, prestigious intelligence assignment awaited him. Instead, he was given a staff billet at Western Sea Frontier Command in San Francisco—far from the front lines of the war he had done so much to shape.

In 1943, he was given command of a floating dry dock. It was a necessary job, but hardly the role one would expect for the man whose work had made Midway possible.

He spent the rest of the war in administrative roles, never again sitting at the center of codebreaking operations.

In 1945, he received the Legion of Merit. Admiral King himself, still irritated by Rochefort’s earlier independence, objected even to that. To King, questions of chain-of-command mattered more than the fates of carriers and pilots influenced by Rochefort’s intelligence.

The Distinguished Service Medal did not come until 1985—nine years after Rochefort’s death. The Presidential Medal of Freedom followed in 1986.

He never saw them.

He died in 1976, believing his work had been largely overlooked, his role in one of the war’s most crucial battles obscured by bureaucratic resentment.

Yet Nimitz, in his private writings and public statements, never forgot.

Again and again he said that without codebreaking, Midway would have been lost. Without Midway, the war in the Pacific would have devoured far more lives and years.

In quiet corners of naval history, the man in the red smoking jacket found his immortality.

— — —

Others paid in different currencies.

Wade McClusky, whose decision to keep searching had made the discovery of the Japanese carriers possible, barely escaped his attack alive.

As he pulled out of his dive after hitting Kaga, two Japanese Zeros dropped onto his Dauntless from behind. Bullets stitched his aircraft, punching through metal and canvas. One round smashed into his shoulder, ripping through muscle, narrowly missing his lung.

His rear seat gunner, Aviation Radioman First Class William C. Chochalouse, swung his twin .30-caliber guns around and fired back, managing to shoot down one attacker.

McClusky, bleeding and almost out of fuel, coaxed his battered aircraft back toward Enterprise. His gauges hovered near empty when he lined up with the carrier deck. He landed with less than five gallons left in his tanks.

Ten other dive bombers from his squadrons were not so lucky. Their engines sputtered and died over open water. Pilots and gunners bailed out or ditched. Most were never found.

McClusky received the Navy Cross. After the war, he stayed in the Navy, commanded the escort carrier Coral Sea in the Atlantic and Pacific, and retired as a rear admiral in 1956.

He died in 1976, the same year as Rochefort.

Admiral Nimitz wrote that McClusky’s judgment on June 4th—the decision to keep searching, the inference drawn from a lone Japanese destroyer racing to rejoin its fleet—had determined the fate of the carrier task force and, with it, the outcome of the battle.

Richard Best, the man who had shifted his dive mid-plunge to hit Akagi instead of doubling up on Kaga, paid his own price.

During his dive, his emergency oxygen system malfunctioned. He inhaled air contaminated with caustic soda-lime granules from a defective canister. The chemical burned his lungs from the inside.

He didn’t feel it immediately; adrenaline masked the worst of it. He completed his attacks, returned to the ship, finished the day.

Then his health began to unravel.

He developed severe tuberculosis, his damaged lungs unable to fend off infection. He would never fly in combat again. In 1944, at only 33 years old, he was medically retired.

Like McClusky, he received the Navy Cross. Unlike so many others at Midway, he lived long enough to see historians try to tell the story of the battle.

In his later years, he became a guardian of its truth, correcting the myths that had grown up around it—especially the comforting fiction that the Japanese had been mere minutes away from launching an attack when the American bombs fell.

No, he told interviewers. Their decks had not been filled with fully fueled, armed planes poised for takeoff. That image came from flawed postwar accounts. The reality was more subtle, and in its own way more remarkable: the Americans had not snatched victory from the brink of defeat by seconds.

They had built it over months of codebreaking and careful positioning, then seized a fleeting tactical window with courage and skill.

Midway, Best insisted, was not an accident.

It was earned.

— — —

Admiral Nimitz stayed at his post until the war ended.

From his headquarters, he orchestrated an island-hopping campaign that bypassed heavily fortified Japanese positions and focused instead on key strategic points: Tarawa, Kwajalein, Saipan, Guam, Iwo Jima, Okinawa.

Each assault was a bloody, brutal struggle. Each success tightened the noose around Japan’s empire.

Nimitz, calm and methodical, balanced the impetuous aggression of Admiral William F. Halsey and the cool precision of Raymond Spruance, assigning each to campaigns that suited their temperaments. Where Halsey drove hard and fast, Spruance planned meticulously, achieving objectives with grim, efficient competence.

Spruance, the quiet, scholarly admiral who had commanded Task Force 16 at Midway in place of the more famous Halsey, became one of the war’s most effective leaders. He directed the Central Pacific campaign, landed Marines on fiercely defended beaches, and oversaw operations that cracked open Japan’s defensive perimeter.

In September 1945, aboard the battleship Missouri in Tokyo Bay, Nimitz signed the Japanese Instrument of Surrender on behalf of the United States Navy. His pen strokes marked the official end of the war that had begun, for him, with smoke over Pearl Harbor and doubt in every direction.

He never forgot Midway.

In speeches and interviews afterward, he credited intelligence again and again. Codebreaking, he said plainly, had shortened the war by years and saved countless lives.

What he did not always add, but surely knew, was that those codes would have meant nothing if American sailors and pilots had not fought as they did.

It was the marriage of information and courage that had turned the tide.

— — —

After the war, Japanese admirals wrote memoirs. Historians interviewed surviving officers. Diaries emerged from dusty drawers.

Admiral Ugaki’s journal, in particular, provided a window into the mental shift that Midway enforced.

On June 5th, 1942, his first explanations for the defeat focused on reconnaissance failures and questionable tactical choices.

By June 7th, after digesting further reports, he noted with unease that American intelligence had been far better than expected.

By June 10th, he was writing about the need to fundamentally reevaluate American capabilities—to accept that the enemy possessed not only industrial might, but also skill, ingenuity, and determination.

That change in tone—reluctant, slow, but real—said more about Midway’s true legacy than any single explosion or burning carrier.

Before the battle, Japanese officers had read training manuals that described American forces as clumsy and predictable. They had been taught to see Americans as undisciplined, lacking spiritual strength, overly dependent on technology they did not fully understand.

After Midway, new bulletins circulated warning that American pilots were highly trained and aggressive, their carrier operations sophisticated, their intelligence capabilities disturbingly effective.

Sailors who had watched Kaga, Akagi, Soryu, and Hiryu die no longer believed in easy victories.

They knew, from bitter personal experience, that being underestimated by your enemy could be a weapon.

A weapon America had wielded well.

— — —

Years after the war, tourists would stand on the deck of the USS Missouri in Pearl Harbor and look down at the bronze plaque marking where Japan had signed the surrender.

Others, on different days, would peer over the railings of museum carriers—Enterprise’s sisters preserved in harbor exhibits—trying to imagine what it felt like to stand on that narrow flight deck while the world burned around you.

Most would never know the names of the men in HYPO’s basement.

They might recognize Nimitz, Halsey, or Yamamoto. They might know of Pearl Harbor and perhaps Midway, in a vague way, as a turning point.

But they would not feel the cold air of that codebreaking room, or the ache in Rochefort’s shoulders as he bent over yet another intercept at three in the morning.

They would not feel the moment when McClusky, staring at an empty horizon, had to decide whether to trust his instincts and burn precious fuel on a guess.

They would not hear Richard Best gasping in a damaged cockpit, lungs burning, as he adjusted his dive by degrees to switch targets mid-plunge.

History tends to flatten such moments into dates and names, arrows on maps and bullet points in textbooks.

But wars turn in other ways.

They turn on exhausted men refusing to sleep.

On bruised shipyard workers swinging hammers through the night.

On pilots who choose to search a little longer.

On torpedo crews who fly into certain death so that someone else’s bomb might find an undefended deck.

On enemies who think you are weak—and on your willingness to let them believe it, just long enough to strike.

At Midway, Japanese admirals watched the ocean claim their carriers, their best pilots, their carefully laid plans.

They watched American dive bombers climb away from burning decks.

They read intelligence reports that spoke of American messages appearing where they should not, American carriers showing up where they had no right to be.

They saw their own doctrine rewritten in the shadow of defeat.

And slowly, painfully, they stopped underestimating the men who had faced them across the water.

Because in four terrible minutes on June 4th, 1942, American sailors and pilots—and the hidden codebreakers who guided them—proved something that no amount of prewar arrogance could erase:

They were not soft.

They were not predictable.

They were not inferior.

They were, in every way that mattered, a match for any navy on earth.

And once Japanese admirals understood that, truly and completely, the war they thought they were fighting was already lost.

News

CH2. The Day Japan’s Oil Lifeline Died — And Its War Machine Collapsed Overnight

The Day Japan’s Oil Lifeline Died — And Its War Machine Collapsed Overnight The convoy moved like a wounded animal…

CH2. How One Girl’s “CRAZY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 TIMES Faster

How One Girl’s “CRAZY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 TIMES Faster Liverpool, England. January 1942. The wind off…

CH2. She decoded ENIGMA – How a 19-Year-Old Girl’s Missing Letter Killed 2,303 Italian Sailors

She decoded ENIGMA – How a 19-Year-Old Girl’s Missing Letter Killed 2,303 Italian Sailors The Mediterranean that night looked harmless….

CH2. Why Patton Alone Saw the Battle of the Bulge Coming

Why Patton Alone Saw the Battle of the Bulge Coming December 4th, 1944. Third Army Headquarters, Luxembourg. Rain whispered against…

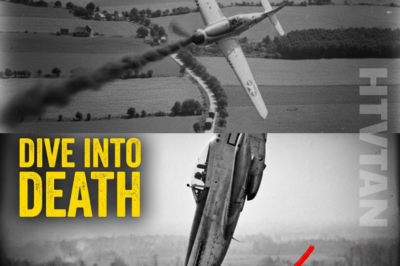

CH2. They Mocked His P-51 “Suicide Dive” — Until He Shredded 12 Enemy Trucks in a Single Pass

They Mocked His P-51 “Suicide Dive” — Until He Shredded 12 Enemy Trucks in a Single Pass The Mustang dropped…

CH2. How 1 British Boarding Party Stole Germany’s Enigma Machine From a Sinking U Boat

How 1 British Boarding Party Stole Germany’s Enigma Machine From a Sinking U Boat The North Atlantic in May was…

End of content

No more pages to load