When I was fighting for my life in the ICU, my own brother made a shocking confession — he sold my apartment in downtown Moscow for just $65K. What he didn’t know was that his little secret would cost him everything.

Part I — The Confession

The ceiling above the ICU bed was a pale, indifferent gray. It reminded me of November in Moscow when the sky forgets how to move. The ventilator beside me breathed with a patience I didn’t have. My daughter slept in a heated bassinet, swaddled, a soft bundle that made the machines feel like lies.

I was twenty-nine hours past an emergency C-section gone complicated, my pulse stitched to a monitor’s logic, when my family arrived shoulder to shoulder, three shadows swallowing the doorway: my mother with her lacquered hair, my father with his winter coat still buttoned to the throat, and Misha—my brother—brimming with a victory that made the air thin.

“You were lying here,” he began, voice lilting like a toast, “and I solved a problem.”

He held up a thin folder as if it were a bouquet. Inside, documents gleamed: a sale contract, a receipt, a notary seal stamped so hard the paper bruised. “We sold your apartment,” he said. “Sixty-five thousand dollars. Quick, clean. Family helped. You’ll live with Mama until you’re better.”

The word better tugged like a hook. I thought of the little two-room on Tverskaya I’d bought by letting myself want nothing else for five straight years—copywriting by day, translations at night, falling asleep on the metro with a notebook in my lap. The first time I’d turned the key, my hands had shaken the way your hands shake when you’ve carried a thing too far and finally put it down where it belongs.

“It was empty,” my mother added. “And you have a baby now. Expenses. We made it simpler.”

Simpler. The scar below my navel hummed. My father’s mouth curled the way it does when he thinks he’s managing outcomes. “Be grateful,” he said. “Misha got a good price; a friend of a friend. You weren’t using it.”

The nurse at the door took a step in then thought better of it. I smiled at her without teeth. I smiled at my daughter with all the softness I had left. I smiled at my family like a woman who hears thunder and notes which way the wind is moving.

“How?” I asked.

“A general power of attorney,” Misha grinned. “We found the old one you gave me when you went to Thailand, remember? The notary confirmed everything.”

“I revoked that two years ago,” I said.

He blinked. Then the swagger came back in, a tide that didn’t know how to do anything but return. “Then it’s another one. Same result.”

Behind him, my mother nodded to my father as if they’d successfully reseated a painting. “Family sacrifices for family,” she said. “You focus on your health.”

I reached for the water. My hands shook only as much as the room required. My phone lay in the plastic hospital drawer, screen dark. I slid it into my palm under the blanket. The voice recorder caught, cool as a blade. I let them talk. I let my brother’s pride give me the date and the notary name and the cashier’s check. I let my mother say the price—“Sixty-five thousand, can you imagine?”—with a thrill as if she’d won a raffle. I let my father laugh, that sound like ice in a glass, about wiring part of it “off the books” so taxes wouldn’t eat it.

When they left, I kissed my daughter’s cheek. “What they did is a beginning,” I whispered. “So is what we’re about to do.”

The ward lights softened to night. My body hurt everywhere the surgeon had touched and in places no one could see. I lay awake and replayed the recording two, three times. It was everything confession always is when it forgets it could be heard—arrogant, exact, helpful.

I sent the audio to my personal email, to a new cloud folder with a name no one would guess, to a friend in Rome who owed me a favor and didn’t ask why I was sending her a sound file at two in the morning Moscow time. Then I texted a name I hadn’t needed since the day I’d bought the apartment: Anna Petrova, the lawyer who had guided me through inheritance laws and bank loans, through Rosreestr’s quiet halls, through the thin thrill of getting a stamp that says yes.

“Can you come to Botkin Hospital?” I wrote. “Urgent. Fraud. I have proof.”

She arrived at noon with a wool coat and eyes like gravity. We sat in the cafeteria with a tray of tea we didn’t drink. I showed her the documents they’d waved over me like spoilers. She flipped them with a pianist’s touch until she reached the signature that was supposed to be mine.

“They over-practiced your new last name,” she said. “People always do when they forge. The curve is wrong.”

I played her the recording. She listened without interruption, then pressed her lips together in a line that meant someone had made her job easy and she disliked them for it.

“We’ll file a statement with the Investigative Committee,” she said, “and a petition to Rosreestr to suspend any further actions on the property. We’ll notify MFC and Rosfinmonitoring to flag the proceeds. This is Article 159 of the Criminal Code—fraud—potentially 170.1 for illegal registration. If the notary is complicit, that’s 327—document forgery. We move now.”

“I’m in the hospital,” I said.

“Then we move from here,” she said. “The law does not require you to stand to tell the truth.”

By dusk she had me sign a complaint with a hand that had held my daughter and would now hold something else. I authorized her to act for me explicitly. She sent a courier to Rosreestr to file a заявление о приостановлении. She called a contact at the police division for economic crimes. She texted the notary’s registry number to someone who would check it.

“Rest,” she said when she left. “Or as close as you can come.”

My daughter slept with her mouth open, a small O the shape of every promise I had ever made myself. I tucked the blanket around her and wrote in the journal my grandmother had given me when I was thirteen: “When they call you the vulnerable party, remember you are also the party that knows how to aim.”

Part II — The Paper and the Knock

I was discharged forty-eight hours later. My family offered to fetch me; I refused with a word that meant more in my mouth than it ever had. Sergei—a friend from university with a license as an investigator and the patience of a chess player—drove me home in a car that didn’t ask questions.

“Body cam?” I asked.

He tapped his lapel. “Always.”

We stopped at my parents’ to collect the things they’d promised to “help store,” which would mean reassign if I gave them enough time. My sister Kira opened the door wearing my silk robe and holding a mug that read girl boss in English. It hit me with the clarity of a street sign. I almost laughed.

“You look like you came to apologize,” she said.

“I came for my clothes and my child’s things,” I said.

“Take your clothes,” my mother said from the hallway, lips in a line that pretended to be mercy. “We redecorated the rest.”

Redecorated, that gentle word people use when they move other people’s lives around as if they were cushions. While they moved their mouths, Sergei’s small camera caught my father saying the frames were “old” and the blender “too expensive anyway,” and Misha saying the buyer was “a decent guy” and that anyone would “jump” at sixty-five cash. It caught the casual knowledge of a theft so normal they hardly noticed doing it.

On the way to the car my father followed, the cold making his breath look like smoke. “Family doesn’t sue family,” he said.

“You should have remembered that before you sold mine,” I said.

That night, Anna texted a photo of stamped papers. The court had granted обеспечительные меры—interim measures—to freeze any movement on the title and suspend the buyer’s registration proceeds. The MVD had assigned a detective. The notary’s license was under review. Rosreestr had flagged the record.

The next day, the investigator from the economic crimes unit called me for a statement. I told my story from a chair with a heating pad pressed to my healing belly and a newborn asleep on my chest. The detective’s questions were indifferent. The law could be that if you trusted it.

By Friday, the prosecutor’s office had my file. By Friday at noon, my brother had my number.

“Clara,” he said, voice thin. “This got out of hand. We can fix it. Mama says—”

“I’m not negotiating the price of my life,” I said. “And you don’t say Mama anymore when you’re talking about a crime.”

“I’ll pay you back,” he said. “When we sell the dacha.”

“You’ll be busy,” I said. “Answer your door.”

A pause. A muffled voice in the distance. My father: “Who is that?” Then a knock that sounded like truth. Then the line went wild with noise—footsteps, my mother’s high cry, my brother’s breath.

“Police,” a voice said. “Open up.”

I ended the call because some things you don’t need to watch, you only need to know.

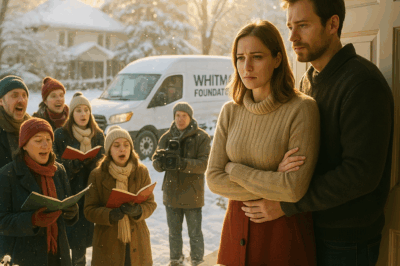

The news got it by evening. They always do when someone in a good coat takes a ride down the stairs of a building you thought was yours. The reporter spoke with the urgency of someone who had been denied scandal and finally got a plate. My father lifted his chin and argued. My mother clutched her pearls like clichés you only take out on holidays. Misha looked young for the first time in ten years and then older than our father ever had.

I held my daughter and watched the footage without heat. Anna phoned. “They’re being interviewed separately,” she said. “Your brother is going to say he thought it was legal. Your father will say he did nothing. Your mother will say she signed nothing. Your recording makes all three of them liars.”

“Will the buyer keep the flat?” I asked.

“He’s a problem for the buyer and the notary now,” she said. “If he didn’t know, he gets his sixty-five back from them. If he did know, he gets a sentence. Either way, your title returns.”

Two days later, the judge voided the transaction on the grounds of fraud and forged authorization. Rosreestr reversed the entry. The MFC clerk who had smiled at me when I first got the stamp smiled again when she handed me the new printout. “Congratulations,” she said. “You taught the system to do what it’s supposed to.”

Part III — The Cost

They were charged in a way that made my grandmother’s voice in my head go quiet and satisfied. Article 159—fraud. 170.1—registration of rights based on false documents. 327—forgery. The notary who had stamped too hard lost a license he shouldn’t have used. The buyer sang like a bird who sees a cat; I didn’t care whether he hit the right notes. My brother’s things were removed from his gym locker by someone who did it gently. My father’s name came up in a way that meant he would spend more time in rooms with fluorescent lights than he was used to. My mother wrote letters on thick paper with blue ink that smelled like a memory of love. I didn’t answer them. The prosecutor’s summary was one page: coordinated familial fraud against a vulnerable party—committed in a hospital room.

The only time I used the word vulnerable was when I pushed the stroller up the five flights to the flat and realized I was strong enough to do it and wise enough not to. I bought a folding ramp. It solved the part of the problem that was mine.

Three weeks after my keys turned in a lock that knew them, I found the courage to stop waiting for the door to be knocked down. My daughter’s mobile sent little moons chasing each other across her ceiling. The city hummed the way only ours does—a low, forgiving noise. Anna came by with cheap champagne and two plastic flutes.

“You want revenge?” she asked, half the lawyer still and half the friend who’d watched me fight myself and everyone else.

“No,” I said. “I want to build a thing that makes this cost fewer people their hearts.”

We founded the Weston Fund for Financial Justice in April, names on paperwork that didn’t tremble, the first mission plain: teach women how to put things in writing and lock them, how to revoke a power of attorney in every registry where it still might whisper, how to record with courage when a room expects you to swallow. We got a small office above a bakery that smelled like morning. We got a website that worked. We got three cases in the first month and returned two flats and a summer house. We taught a woman on the edge of forty how to ask a notary the right questions. We taught her daughter how to record.

In June I took my daughter, Lena, for a walk along the Boulevard Ring. A text came from an unsaved number: “We lost everything. Can we see the baby?” It was my mother’s voice wearing my sister’s spelling.

I typed: “She is safe. She will never learn love the way you taught it.”

Then I pressed block. The quiet that followed had weight and a temperature. It was not empty. It was room saved for someone else.

Part IV — The Ending

In late summer, a light bounced off the old oak floors just so and the flat smelled like the lavender oil I’d always put in the radiator pan to fight winter’s dry air. Lena toddled, wobbled, planted her hands on the sill, and shouted at the pigeons as if they’d answer in Russian or in coo. My phone pinged with a bank notification: the buyer’s sixty-five thousand had been repaid to the state; the damages had cleared into a trust in my daughter’s name. Money—what they had tried to make everything—now sat where it could do only one job and no harm.

Misha sent me a message through Anna’s office, the kind you give to someone in case it counts: an apology without an admission, an admission without a heart. I wrote back through my lawyer: “If you wish to demonstrate change, there is a recovery group that meets on Thursdays; you can volunteer at the shelter our fund partners with on Saturdays; send me your attendance once a month for a year. After that, we may talk.” He did, for a while. Then he didn’t. We will see. The door without a lock is not always the right door.

On the anniversary of Lena’s birth, I took her to the ICU ward with a cake for the nurses. They remembered my scar and my daughter’s small mouth and the way my family’s voices had sounded in that room. “We’re glad,” one of them said, “you recorded.”

“So am I,” I said. “That was the first time I let myself believe I wouldn’t be punished for telling the truth.”

The city’s first snow came late that winter and fell with a patience I recognized. I stood at the window of the apartment they had tried to sign away and watched Moscow soften its edges. Lena pressed her palm to the glass and laughed. The whole world was an untaken thing she could claim with a sound.

I thought about the word vulnerable again, in the prosecutor’s file. It had saved me. It had also lied. Vulnerable is a state. It is not a sentence. I had been weak; then I had been precise. I had been loved badly; then I had been useful.

Family should protect you. If they don’t, the law should. If the law doesn’t, your recording should. And if all else fails, you should. You do not have to be standing to be the one who decides.

When I finally slept that night, I dreamed of my grandmother wiping down a table after tea, the way she’d erase a mess and leave the wood shining. “Never stay quiet when truth is on your side,” she’d written in the front of the journal. I had stayed quiet a long time. I stopped. That, more than anything, is what cost them everything.

Justice didn’t knock down the door shouting. It came as a stamp on a form, as an email from Rosreestr, as a judge’s single page, as a bank’s polite note. It came as my daughter’s step toward me on the old oak floor that had learned our feet and chosen to keep us. It came as a new word on the door buzzer: Weston. It came as silence where shouting had been, as the sound of a woman in a high stairwell carrying a sleeping child who would never, if I could help it, learn betrayal in a hospital room.

Some stories end with punishment. Mine ends with a key turning in a lock that was always mine.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. My Niece Texted Me, “You’re Not Welcome At My Graduation. Stay Home, Loser.”

My Niece Texted Me, “You’re Not Welcome At My Graduation. Stay Home, Loser.” My Sister Added A Thumbs-Up Emoji. I…

CH2. My Wife Mocked Me in Front of Her Boss — I Left the Party, and That’s When Her Life Fell Apart

My Wife Mocked Me in Front of Her Boss — I Left the Party, and That’s When Her Life Fell…

CH2. My Family Said:”You’ll Firgue It Out” After Moving Away Without Me At 17—When I Made It, They Tried…

At seventeen I was abandoned by my family. I came home to an empty house and found only a note…

CH2. “There’s No Place For You Here!” My Daughter-In-Law Said On Christmas, So I Left. The Next Day…

“There’s No Place For You Here!” My Daughter-In-Law Said On Christmas, So I Left. The Next Day… Part I…

CH2. At Thanksgiving Dinner, My Sister’s Kid Threw His Fork at Me and Said, “Mom Says You’re the Help…

At thanksgiving dinner, my sister’s kid threw his fork at me and said, “Mom says you’re the help.” The table…

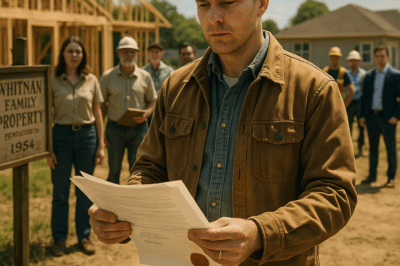

CH2. HOA Built on Our Land Without Permission—They Panicked and Ran When We Came Back Armed!

HOA Built on Our Land Without Permission—They Panicked and Ran When We Came Back Armed! Part I — The…

End of content

No more pages to load