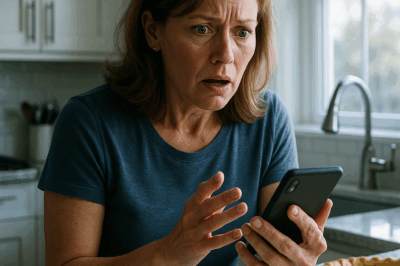

When I Threw Away the Child Seat My MIL Gave Us, My Husband Yelled, “Mom gave that to us!”

Part I — The Gift That Wasn’t

The baby seat was beautifully wrapped—cream ribbon, silver tissue, a handwritten card from my mother-in-law with a flourish under her name. “For Liam,” it read. “Nothing is more important than safety.”

Tom’s whole face softened when he saw it. “Mom thought of everything,” he said, almost reverent, as if the box were a blessed object. He brushed a kiss over our son’s sleepy hair and carried the seat into the living room like he was carrying a family heirloom.

I smiled. I said thank you. I set it on the rug.

And then, when the front door closed and the house fell quiet, I lifted the cover and unzipped the lining. Not because I expected anything. Because with Sylvia I had learned to expect everything.

What spilled out of the seams made my stomach pitch.

Maggots. Alive, pale, writhing in a slow, obscene drift beneath the foam.

I froze, then went cold with a kind of murderous clarity I didn’t know I owned. I sealed the cover with one hand, grabbed my phone with the other, and hit record.

“Safety,” I whispered to an empty room, “isn’t a word you get to write anymore.”

I have a shellfish allergy. For three years, Sylvia “forgot” and turned up with king crab and lobster, making Tom light up at the door while I swallowed humiliation in the kitchen. She criticized my sewing. She commented on my face. She mentioned—offhand, smiling—that some women shouldn’t have children if they hadn’t been “raised right” themselves. And every time I told Tom, he laughed gently, wiped my cheek, and said, “Mommy’s just thoughtless. She doesn’t mean harm.”

Mommy.

He is gentle and capable in almost every way—but his devotion to his mother is a bruise that never fades. He compares unconsciously. “Mom bleached sheets in the sun—it keeps them whiter.” “Mom filleted fish fresh—you can taste the difference.” “Mom says we don’t need a dryer—line drying smells like childhood.”

I never yell. I remind. I think that was my mistake: if you make reminders soft, men can pretend they’re suggestions.

Liam arrived in winter after three days of sleep and ten hours of labor and exactly one nurse who understood I was terrified. Sylvia arrived the next day and never left. She brought a notebook full of names for our child we did not ask for. She stood at the window and said, “Thank God he looks like Tom.” She kissed his forehead and did not once ask me how I was healing.

So when the child seat arrived—on a random Tuesday, with a tender note and perfect gift wrap—I didn’t trust it. I picked it apart and found what she’d buried.

There are lines you don’t step over with a new mother. There are lines you don’t step over with any living thing.

This was not a line. This was a cliff.

I zipped the cover and walked outside.

I didn’t walk to the nursery.

I walked to the communal garbage room and lifted the lid.

I set the seat on top of the bin and exhaled.

And just as I turned to call Tom, he came running down the hall like he’d been watching from the second floor: face red, hands furious fists.

“What are you doing?” His voice cracked. “Mom gave that to us!”

That voice—not his courtroom voice, not his bedtime story voice, but the voice he uses when something threatens his mother—bounced inside my ribcage.

“You threw away the child seat Mommy gave us,” he shouted. “It’s—It’s divorce!”

He actually said the word. It hung there between us, a tear in the air.

I didn’t raise my voice. I didn’t cry.

I reached into the box, unzipped the cover, and pulled the lining open like a wound.

“Is this enough?” I asked.

The color left his face in one clean movement. He recoiled like the seat had hissed at him.

“What—” He swallowed. “What is that?”

“Maggots,” I said, and held his gaze until he had to look away.

Then I pressed play on my phone.

Sylvia’s voice filled the hallway, bright and venomous in equal measure.

“You never keep things clean, Amanda. Poor Liam. He’d be better off with us.”

“That’s lace? It looks like you ripped up a curtain.”

“We’ll bring lobster. It’s time you grew up about these childish allergies.”

“This child is unfortunate to have a mother like you.”

Clip after clip, little cruelties she delivered with a pat on the shoulder and a smile, recorded in the quiet moments when she forgot she was being watched by someone other than herself.

Tom’s eyes shone. Not with rage. With shame.

“I’ve said this many times,” I told him. “I’m not your mother. And I am not your mother’s maid. You asked for proof. Here it is. If you still side with her after this”—I tapped the phone, tapped the seat, tapped my wedding ring—“I’ll consider that your divorce.”

He didn’t answer. He stared at the seat like it might answer for him.

He said, “I’m sorry.”

He said it like an oath, not an excuse.

He said, “I can’t believe she did this.”

And the ground under my feet, which had felt like thin ice for months, turned to concrete.

“Good,” I said. “Then you’ll help me return the gift.”

Part II — The Return

We drove to Sylvia’s house the next morning. I held Liam on my hip and the seat in my hands. Tom carried a large box wrapped in gold paper. He rang the bell with a steadiness I had never seen in him when it came to her.

She opened the door with a practiced smile and a delighted gasp. “A vacuum?” she squealed when she saw the box. “Tommy, you remembered!”

She tore the paper.

She screamed.

Maggots, in daylight, look less like horror and more like arrogance. They say, “This house is mine now.”

“What is wrong with you?” she shrieked, recoiling. “How dare you—”

“No,” Tom cut in. “How dare you.”

She stopped. The wall clock ticked so loudly I could hear the second hand hit bone.

“What are you talking about?” she tried, voice lilting back to sweet. “I don’t know—”

“I went to the tackle shop,” Tom said. His voice did not rise. It pressed. “The one Dad used to take me to. I asked the owner if anyone had purchased a three-pint cup of maggots this week. He said yes. He remembered you.”

She blinked.

He laid the receipt on the coffee table with the kind of finality judges have to practice to get right.

“It wasn’t supposed to hurt him,” she said quickly, words falling over one another. “It was supposed to hurt you. You’re sloppy. You don’t know how to keep house. I was going to come over and—”

“Save him from the mess you made?” I asked.

She flinched.

“It was just an idea,” she said, desperate. “If the seat got dirty, child services might—”

“Take our son,” Tom finished, horror finally outpacing shame. “Do you hear yourself? Do you hear what you planned?”

“He’s my grandson,” she snapped, as if affection were a permit. “He belongs with family. With us. You don’t know what you’re doing. You stole my son and you’re ruining my grandson.”

Tom didn’t look at me. He didn’t look at the seat. He looked at the photo of himself on her mantle—the one where he’s eight, holding a fish longer than his arm, grinning into the sun—and he whispered to that boy, to all the boys who never got to say it:

“Enough.”

Then, to Sylvia:

“You are not welcome in our home. Not until you understand what the word ‘unsafe’ means.”

She lunged forward, hands out, sobbing theatrically, the way she did when she wanted to rewrite a moment by flooding it.

“Tommy, you don’t mean that. You can’t say that to your mother—”

“I just did,” he said.

She turned to me. “Amanda, tell him to stop being ridiculous. You’re a mother. You know what this means.”

“I do,” I said. “It means you won’t be seeing my child.”

She sank into the armchair like it was a trap. The room felt smaller than the seat of our car had.

“We’re getting a restraining order,” I added.

That broke her composure. The tears went jagged. The rage surfaced. “You’re abandoning me! After everything I did for you, for him—”

“Stop,” Tom said, an adult, at last, speaking to a woman who only knew how to mother a boy.

We left without slamming the door. Some endings deserve civility. It makes the boundary louder.

Part III — Paper Is a Kindness You Learn Late

The police officer who came to take our statement listened like he’d heard this story three hundred times and still couldn’t believe it had to be told. He said the words you only hear when the situation is already too far gone: “temporary protective order,” “probable cause,” “document everything.”

We did. We documented the delivery. We documented the fishing receipt. We documented the texts that arrived after we left—twenty-seven in two hours, in which Sylvia cycled through apology, denial, blame, nostalgia, and weaponized frailty.

Tom blocked her.

Not out of anger. Out of duty.

He deleted “Mommy” from his phone and replaced it with “Sylvia” in case it ever slipped through in an email or a new number.

He changed the locks, rewired the doorbell camera, and started doing a thing he had never done before: laundry without commentary, dishes without notes about sun bleaching, dinners without comparisons. The quiet was like healthy blood pressure—so ordinary you cried at how rare it felt.

He apologized again. Not performatively. Practically.

“I’m going to couple’s counseling,” he said. “By myself first. You don’t owe me attendance just because I need homework.”

He started drawing boundaries like a man who had discovered fences are not just to keep things out. They are to keep children safe inside.

He called the pediatrician and scheduled Liam’s well-child visit without prompting. He showed up to the parent-baby class with two extra burp cloths and a bottle warmer he actually learned to use. He learned the names of my stitches and the way I like my tea and the specific shade of tired behind my jokes.

Men don’t get credit for becoming adults. They also don’t get forgiven for it. But watching him try felt like discovering the house had a foundation after all.

We moved across town three months later. Not out of fear. Out of strategy. The lease was up. The court order was in place. The past address was just a place where something had happened. The new address was where things would.

Part IV — The Last Knock

The last time Sylvia came to our door was the last day she legally could.

She pounded so hard I could smell the varnish of the wood. “Let me see my grandson!” she cried. “I’m still his family!”

I didn’t answer. The camera recorded. Tom forwarded the clip to the officer and the attorney. Paper did its slow work.

Two hours later, she sent a voicemail I didn’t need to hear to know its contents: memories she’d weaponize, holidays she’d claim, a childhood she’d rewrite until there was no oxygen left in the room.

I deleted it unheard.

Some people only speak to be the echo in your head. Silence is a medical intervention.

Part V — What We Kept

We kept the seat. Cleaned. Sanitized. New cover. New foam. Not because we needed it. Because we needed to own it. Pain you control becomes history, not prophecy.

We kept the videos. Not because we rewatch them. Because they are the flashcards Tom uses when his old reflexes flare—when he hears a woman at the grocery store call her adult son “my baby” and for a moment thinks of sun-bleached sheets instead of maggots.

We kept each other. Not as a performance piece for a woman who needed an audience. As a habit you maintain because it’s yours.

One evening in June, Tom set Liam in the bouncer and knelt on the kitchen floor to loosen the high chair screws so I could adjust the height. His hands were steady. He didn’t tell me how his mom did it. He didn’t tell me who was better at fish.

He said, “What does dinner look like to you tonight?”

I said, “Shredded rotisserie chicken tacos and joy.”

He laughed—the kind of laugh that doesn’t leave a bruise.

He said, “I can do that.”

He did.

Part VI — The Ending People Ask For

People love redemption, but they prefer it to happen before it costs them anything. If you’re waiting for the scene where Sylvia stands on our porch with flowers and a therapist’s bill and a letter that begins, “I’m sorry I mistook control for love,” you’ll be waiting a long time.

There was no apology from her that would make me open the door. There was no apology from Tom that would make me forget. There was only the daily evidence that we are, finally, the parents we promised Liam he would have: a mother who will throw out a “gift” without asking permission, and a father who will not make her defend it when she does.

A year later, Tom took Liam to the tackle shop—because boys deserve to learn that history can be rewritten. He bought worms. He taught our son to set them gently back in the dirt when they were done. He told him bugs help things grow.

He told him, “This is where Dad learned to do things the wrong way. And this is where I learned to do them right.”

They came home with a small fish and a photo. In the photo, Tom is not eight. He is exactly his age. His mouth isn’t open in pride. It’s open in laughter. There’s no mantle this belongs on. There’s a refrigerator where love goes while it’s still alive.

That night, after Liam finally surrendered to sleep, Tom washed the high chair tray and laid it to dry without speaking. Then he took my hand, not for sex, not for show, but for proof.

“Thank you,” he said.

“For what?”

“For throwing it out,” he said. “For not needing me to believe you in order to protect him.”

I squeezed his fingers. “We did that part together,” I said.

We did.

And when the doorbell rings now, it’s friends, not ghosts.

The child seat is strapped safely into the car we bought with our own money. There’s a small scratch on the base where I pried off the old cover and threw it away. I run my finger over it sometimes on the way out of the driveway.

It feels like a seam on a healed wound. Not quite smooth. Not quite tender. Evidence.

We buckle Liam in. We go.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. Ten Days Before Thanksgiving, I Found Out That My Daughter Was Planning To Humiliate Me…

Ten Days Before Thanksgiving, I Discovered Something That Shattered My Heart — My Own Daughter Was Plotting to Humiliate Me…

CH2. On My Birthday, I Learned They Took More Than Just My Gifts — What Happened Next

On My Birthday, I Learned They Took More Than Just My Gifts — What Happened Next Part I — The…

CH2. My Dad Removed Me From the $30K Dubai Trip I Funded—To Give My Spot to My Brother’s Fiancée

My Dad Removed Me From the $30K Dubai Trip I Funded—To Give My Spot to My Brother’s Fiancée Part I…

CH2. My Parents Kicked Me Out in a Blizzard. They Said I’d Come Crawling Back, But Then…

My Parents Kicked Me Out in a Blizzard. They Said I’d Come Crawling Back, But Then… Part I — The…

CH2. My parents treated me like a maid, until at my grandfather’s funeral…

My parents treated me like a maid, until at my grandfather’s funeral… Part I — The Smallest Room My mother…

CH2. At Dinner, She Smirked: “My Ex Just Texted – I’m Meeting Him For ‘Closure’ Tomorrow.” I Just Nodded: “That’s Thoughtful.” The Next Morning, Her Bags Were Professionally Packed, The Locks Changed, And A Moving Truck Waiting. When She Came Back From Her “Closure” Meeting… She Realized I’d Already Closed Everything…..

At Dinner, She Smirked: “My Ex Just Texted — I’m Meeting Him for ‘Closure’ Tomorrow.” I Just Nodded: “That’s Thoughtful.”…

End of content

No more pages to load