When A-4 Skyhawks Sank the British

May 25th, 1982, Argentina’s Revolution Day and the 53rd day of the Falklands War… or for Argentina the fight for the Malvinas. Four Argentinian A-4B Skyhawk bombers moved on the British ships that patrolled to the North West. The Royal Navy radar picket had already caused the loss of several Argentinian planes. Now the pilots had the task of bombing Royal Navy ships specifically designed to shoot planes down. The Argentinians had no radar warning, no chaff, just outdated planes, unguided bombs and sheer determination.

The British ships also were in a precarious position – three days of daily patrols without a rest, away from any support besides occasional fighter combat patrols. The Loss of HMS Coventry was a disaster for the British but did not change the course of the war.

The wind coming off the South Atlantic had a taste of iron and ice.

Captain Pablo Carballo stood at the edge of the tarmac, helmet under his arm, staring at the two squat shapes of the A-4 Skyhawks in front of him. The jets were old, paint faded, patched with mismatched panels. Fuel fumes hung over the concrete. Mechanics moved around the aircraft like busy ghosts, tightening panels, checking hoses, wiping grease from hands onto already ruined overalls.

Behind the flight line, the low buildings of Río Gallegos air base crouched against the cold, their windows glowing dimly in the gray morning of May 25, 1982.

He knew the date like he knew his own name. In Argentina, May 25 was a national holiday—Revolución de Mayo—the day they celebrated the birth of their nation. This year, the celebration was different. The country was at war.

Pablo glanced down the line to where Lieutenant Carlos Rinke was joking with a mechanic, miming some broad, ridiculous gesture with his hands. The mechanic laughed, shaking his head, and slapped the side of the drop tank in mock annoyance. Rinke caught Pablo’s eye and winked.

Showtime, boss.

Pablo gave him a nod, more solemn than he felt inside. Or maybe less. Deep down, beneath the hard shell of routine and discipline, something small was shivering.

He looked beyond the runway, to where the sea lay out there somewhere in the gray distance, cold and merciless. Beyond that, another stretch of sea. And beyond that, the islands.

The Malvinas.

The word felt heavy and proud in his chest, but it lived in the same space as fear. A month earlier, Argentina had seized the Falklands from the British. The junta called it a patriotic recovery. The pilots called it a job. The men on the ground called it home, if only in their heads.

Now the British were here to take the islands back—and if they succeeded, all of this, all the blood and fire and cold missions over endless gray water, would have been for nothing.

Pablo’s Skyhawk looked tired. It had been designed long before men had walked on the moon. It had no radar. No real defensive systems. The bombs were iron relics bolted under its wings—dumb, heavy, unforgiving. His only shield would be altitude, or rather the lack of it. They would fly so low their bellies would practically kiss the sea.

And today, he thought, may be a one-way ticket.

A gust of wind snapped at the flags near the control tower and made the halyards vibrate with a metallic rattle. It sounded like something breaking.

“Capitán!”

He turned. A young ground crewman jogged over with a clipboard, breath fogging in the air.

“Last check signed, sir. She’s ready.”

Pablo took the pen, scrawled his name at the bottom. His handwriting looked oddly calm to him. Like it belonged to another man.

“Gracias,” he said. “You get some coffee, muchacho. This is going to be a long day.”

The kid grinned, but there was worry behind it.

“Yes, sir. Good hunting.”

Good hunting, Pablo thought. As if this were some old gaucho’s story about riding out to chase wild cattle, not a modern war fought against one of the most powerful navies on Earth.

He tilted his head back and looked at the sky. Low, gray, and unwelcoming.

“Don’t climb for any reason,” he murmured, repeating the briefing. “You climb, you die.”

It wasn’t poetry. It was mathematics.

He climbed the ladder into the cockpit, the metal rungs cold through his gloves. Settling into the ejection seat felt like slipping into a coffin he knew a little too well. Everything smelled like fuel, oil, and plastics heated by countless flights.

He ran his hands over the familiar switches, the canopy sill, the worn throttle. Under the left side of the canopy frame, there was a tiny sticker peeling at one corner. His daughter had stuck it there the last time he’d been allowed to see family months earlier. A small cartoon sun, all yellow and orange, with the faintest hint of a smile.

“Papa, this is so you don’t get lost in the clouds,” she’d said.

He’d laughed then. Now the memory hurt.

He hit the battery switch. The instruments flickered to life, the cockpit coming awake around him, all humming electricity and the promise of violence. Outside, the ground crew wheeled chocks away and stepped back.

“Azul Uno to Torre,” he said into his oxygen mask. “Requesting permission for engine start.”

His voice sounded steady. That was something.

“Azul Uno, cleared. Buena suerte.”

Good luck.

He thumbed the starter. The engine behind him began its familiar whine, rising in pitch until it became a solid, comforting roar. The cockpit vibrated. The world narrowed. The A-4 was awake.

Beside him, Azul Dos—Rinke’s jet—spooled up as well, exhaust shimmering behind it in a wavering heat haze. Farther down the line, another pair of Skyhawks—Velasco and Barrionuevo—started their own aircraft. The second section, the follow-up punch.

Four jets. Four men. A handful of unguided bombs versus the British task force.

On the other side of the world, Pablo thought, some American flight instructor was probably waking up, going to work, climbing into some sleek F-14 or F-15 with radar that could reach out a hundred miles, missiles that cost more than his entire airplane.

Here, he had iron bombs bolted under stubby wings and hope.

He eased the throttle forward and the aircraft began to roll, gravel crunching under the tires as he taxied. The runway lights barely glowed against the gray. One by one, the Skyhawks lined up, four sharks in a row.

“You ready, Carlos?” Pablo asked.

“Always,” came Rinke’s voice. There was a faint laugh in it, a defense against everything else. “If you see me get lost, just follow the angelic glow I leave in the sky.”

“Just keep your head down and your throttle up,” Pablo replied. “Remember: we go in low. We come out lower.”

The control tower cleared them for takeoff. One by one, they shoved their throttles forward. The Skyhawks surged down the runway like sprinting animals, vibrations hammering through the cockpit, the seat shuddering beneath him.

At a certain speed, the runway fell away.

For a moment, Pablo felt the sweet, weightless freedom that had first drawn him into flying as a teenager. Then he shoved the nose down, forcing the aircraft toward the sea.

Low. Always low.

The gray South Atlantic rushed up at him until it seemed the ocean would swallow the jet in one gulp. He leveled off mere meters above the water. The waves blurred past, streaks of white foam and slate-blue troughs.

“Azul flight, form up,” he said. “Course is set. One-way to the Malvinas.”

Rinke slid into position on his right, close enough that Pablo could see the other man’s helmet turn in a brief nod. Behind them, the second pair fell into place.

Four small jets skimming the skin of the Atlantic, like stones thrown by some invisible hand.

The coastline of Argentina fell away behind them.

Out there, beyond the horizon, the British waited.

In the operations room of HMS Coventry, the air smelled of coffee that had been burnt hours earlier and metal warmed by too many bodies and too many machines.

Captain David Hart-Dyke stood with one hand on the back of the radar operator’s chair, the other wrapped around a mug of that same terrible coffee. The surface-search radar swept its green arm around and around, repainting the world every few seconds. On another screen, the air-search radar traced circles farther out into the sky.

It was the morning watch. Men spoke in low voices, a blend of formal reports and the easy banter of those for whom crisis had become routine. Coventry was a Type 42 destroyer, steel and electronics and history, now stationed northwest of the Falklands as a radar picket, a shield for the rest of the task force.

She was here to be shot at first.

“Sir, Special Forces report again,” the communications rating said, turning from his console. “Intercepted traffic indicates Argentine strike aircraft are airborne.”

Hart-Dyke nodded slowly. He was a tall man, lean, with a face that looked like it had been carved into permanent seriousness by wind and salt.

“Any indication of targets?” he asked.

“Negative, sir. But they’re out there.”

Last week, an Argentine bomb had fallen close enough to another ship that the shockwave had rattled Coventry’s plates. There were stories circulating about bombs punching through ships and not exploding, about luck and strange fuses and pilots screaming home on fumes. There were also stories that began with someone’s first name and ended with the ship’s chaplain.

Hart-Dyke had memorized the routine. He could have given the orders in his sleep. The thing that haunted him was that he might have to.

He glanced at the big digital clock on the bulkhead, then at the chart spread on the table. Coventry and her consort, the frigate HMS Broadsword, were positioned near Pebble Island, their radars reaching out like invisible nets. Their job was to cover the ground forces on the islands from air attack.

The Type 965 radar was good. So was the Sea Dart missile system—on paper. It had already brought down several Argentine aircraft. But the Argentines had learned. They came in low. Very low.

He took a sip of coffee. It tasted like ash.

“Any word from the Harrier CAP?” he asked.

“Sea Harrier Bravo-Three-Four reports on station, twenty miles out,” a controller replied.

Good. Having a Harrier up was like having a boxer’s right hook ready. If the missiles couldn’t do the job, maybe the fighter could.

He set his mug down.

“Gentlemen,” he said, loud enough for the room to hear without shouting. “We’ve been warned. Let’s assume we are the target. I want everyone sharp and ready. No complacency. We’ve been lucky so far; that doesn’t last forever.”

A few heads turned. A few backs straightened.

His radar officer spoke up from his console.

“Air search is clear out to one hundred miles, sir.”

“Keep looking,” Hart-Dyke said quietly. “They like to appear late to the party.”

He didn’t say “and from below.” He didn’t have to. Everyone in this room, from the most junior rating to the highest officer, had the same nightmare: a green contact appearing suddenly at ten or fifteen miles, too low, too close, with too little time.

He glanced at the damage-control status board. It was all green. Bulkheads intact. Firefighting systems ready. It was reassuring and meaningless, he thought. One bomb in the wrong place could turn it all red in seconds.

He put his hand on the back of the operator’s chair again, feeling the slight vibration of the ship through the metal frame. Coventry’s hull cut through the cold South Atlantic, steel and engines and British stubbornness.

“Four contacts bearing two-two-five, range three-zero!” the air-warfare rating suddenly called out, voice sharp.

Hart-Dyke’s stomach tightened.

There it is.

He leaned in.

“Classification?” he asked.

“Fast movers, sir. Low level.”

His heart gave a single heavy thump. There was no reason for anything friendly to be coming in like that.

“Action stations,” he said.

The words were calm. The klaxons were not.

Alarms howled through Coventry’s passageways, echoing off metal walls, jolting men awake in cramped bunks, sending them scrambling to their stations. Boots hammered on ladders and decks. Hatches slammed shut. The crew had practiced this drill dozens of times. This time, their hands shook a little more.

Hart-Dyke’s voice cut through the noise on the internal net.

“Broadsword, what is your status?”

The reply came from the frigate’s captain, his voice crackling over the radio.

“Broadsword here. Sea Wolf is online. We’ll engage anything that gets through your umbrella.”

Sea Dart first, Sea Wolf second. Big fist, quick jab.

Hart-Dyke turned to his missile director.

“Prepare to engage. Priority to the western contacts. Confirm no friendlies in the engagement zone.”

The controller frowned at his screen.

“Sir, Harrier Bravo-Three-Four is twenty miles out, vectoring in. He’ll enter the engagement zone in less than a minute.”

And there it was—the nightmare scenario. Friendly aircraft and enemy aircraft converging in the same slice of sky, with seconds to decide.

Hart-Dyke swallowed. His throat felt dry.

“Put the Harrier on a different heading,” he ordered. “Turn him away. If he doesn’t clear the area, we can’t shoot.”

“Aye, sir.”

The message went out into the ether. Somewhere out there, above the gray waves and whitecaps, a British pilot would be frowning, adjusting his stick, watching his vector change on his heads-up display. A few thousand feet below him, invisible to his radar, four Argentine Skyhawks sliced through the ocean air like knives.

Pablo flew with his eyes flicking between his altimeter and the shifting pattern of waves just beneath his nose.

Two meters. Three. Four. Back to two.

He felt the aircraft nibbling at the air, wings biting just enough to keep him from becoming a smear on the surface. Sea spray flew up in sheets from the wind, leaving droplets on his canopy that salt traced into faint streaks.

“Azul Uno to flight,” he said. “Check in.”

“Azul Dos, good.”

“Azul Tres, on your tail.”

“Cuatro, same. All green, Pablo.”

He could hear Velasco’s voice, slightly tighter than usual. The man was good. Young, but good. Barrionuevo, behind him, didn’t say much. He flew like a man who thought words were a distraction.

Ahead, a darker smudge appeared on the horizon. Land.

“Isla Borbón dead ahead,” Pablo said. “We’ll use the island as cover. Stay low. Follow my lead. Under no circumstances do you climb. British radar will be searching above the terrain—we live under it today.”

He felt them all edging closer in around him, falling into a tighter formation. It was like everyone was subconsciously trying to hide in someone else’s shadow.

He thought of the briefing. Intelligence had indicated two British ships: a destroyer and a frigate. HMS Coventry, a Type 42, and HMS Broadsword, a Type 22.

Coventry meant Sea Dart—long-range missiles that were deadly at altitude, but with a minimum range up close. Broadsword meant Sea Wolf—short-range missiles that could swat down low-flying aircraft if they got close enough.

To survive, he would have to fly in the thin, deadly gap between those capabilities. Too low for Sea Dart. Too fast and close for Sea Wolf to react properly.

He had a sudden, irrational urge to laugh.

This is insane, he thought. And we’re doing it because a map says those islands are blue instead of red.

He shoved the thought away. Nothing good came from letting the politics into the cockpit. His job was simple: get close, drop bombs, get out. Everything else was somebody else’s problem.

As they approached the jagged outline of Pebble Island, he eased slightly left, letting the terrain loom between them and the known position of the British ships. The land was low, but it was enough. Radar beams, like light, could be blocked by hills.

For a moment, the sea fell away as they hugged the island’s contours. The world became a blur of gray rock and dark scrub passing just beneath their wings. The Skyhawks seemed to crawl along the surface of the earth.

“Keep your eyes open,” Pablo said. “We’re in their backyard now.”

Onboard Coventry, the radar operator watched the blips near bearing 225 come in—and then vanish.

“Contacts lost over Pebble Island, sir,” he called out.

Hart-Dyke’s skin prickled.

“Damn,” he whispered.

He knew exactly what that meant. The enemy aircraft had dropped behind the island, hugging the ground. Coventry’s Sea Dart system, with its radars housed high above the water, had a blind spot at close range. The rockets didn’t arm until a certain distance out. If the Argentines popped back up inside that envelope, the destroyer would have a single clean shot—maybe.

Hart-Dyke thought about the Harrier, about the messages that may or may not have gotten through in time. He thought about Broadsword’s promise to cover them with Sea Wolf. He thought about the dozens of men in their bunks and compartments, trusting him to keep this steel home safe.

He looked at the tactical plot.

Pebble Island was too close.

“Hold your course,” he said quietly. “We’ll be ready when they come off the other side.”

If they do, he added silently. If they don’t hit us from somewhere we’re not expecting.

On the far side of the island, the sea appeared again, an endless plain of gray shot with white lines of foam. Pablo scanned the horizon, and this time, he saw them.

Two shapes, low and hard and angular, riding the swell. One with a distinctive boxy superstructure: the destroyer. The other sleeker, the frigate.

“Contact,” he said, unable to keep the edge out of his voice. “Ten miles. Coventry and Broadsword, ahead and to the right.”

“Madre de Dios,” Rinke breathed.

They looked smaller than he’d imagined them. The distance did that. But he knew better than to let the size fool him. Each of those ships carried enough firepower to turn his aging jet into confetti in a second.

His thumb hovered near the bomb-release switches. Not yet. Too far. They would close fast, but they needed to be right on top of the targets for their unguided bombs to have any chance.

He shoved the throttle forward. The A-4 answered with a deeper roar, pushing him back into his seat. The altimeter needle barely flickered—he kept the nose glued to the lip of a wave.

“Azul Uno, commencing attack run,” he said. “Good hunting, muchachos.”

He could almost feel their hearts pounding through the radio.

On Coventry, the air-search radar lit up again.

“Two hostiles bearing one-nine-two, low level!” the operator cried.

Hart-Dyke’s eyes snapped to the display. Two contacts, suddenly there, just fifteen miles out and closing fast, coming in low like torpedoes launched from the sky.

“How low?” he demanded.

“Very low, sir. Must be just above the waves. Sensors are struggling to hold them.”

The controller’s voice was tight with strain as he attempted to maintain a lock.

A second voice cut in from the operations console.

“Sir, the Harrier is still twenty miles out, same sector.”

Hart-Dyke made the decision in a breath. He had to.

“Turn the Harrier away,” he snapped. “Order him clear of the engagement zone. We will engage with Sea Dart.”

He felt the weight of that choice like a physical thing. In another life, another navy, maybe he would have been a fighter pilot himself. Now he was about to fire missiles near a friendly aircraft. A misstep here wouldn’t just be a tactical error; it would be a tragedy.

He watched as the Sea Dart launcher on Coventry’s foredeck turned, raising its twin missiles to meet the threat. In the operations room, the missile director called out numbers.

“Target designated. Trying to achieve lock. Stand by… stand by…”

On the display, the two hostile contacts flickered, their returns uncertain, scattering the radar’s beams with their sea-skimming flight. The system was designed to track targets higher up, to bring down Soviet bombers, not tiny jets flying so close to the sea that they practically wore the ocean as camouflage.

“Why can’t we get a solid lock?” Hart-Dyke asked, anger and fear sharpening his voice.

“Clutter from the waves, sir,” the operator replied, frustrated. “They’re very low. The returns are… intermittent.”

“Broadsword,” Hart-Dyke said over the radio, “we have two hostiles inbound, low level. Engage with Sea Wolf the moment they’re in range.”

Onboard Broadsword, men in their own operations room acknowledged. The Sea Wolf system was newer, faster, designed for exactly this kind of knife-fight at sea. It could track small targets at close range and swat them out of the sky like flies—if it worked the way it had in trials.

“Sea Wolf on standby,” Broadsword’s air-defense officer said. “We have them on radar.”

Both ships waited.

The world had narrowed for Pablo to a single tunnel, and at the end of that tunnel was a gray ship’s side.

Coventry was turning slightly, he could see that. Presenting her bow, narrowing her profile, making it harder for them to get a good hit. Smart captain. It wouldn’t save her.

He felt the jump of his heart in his chest, the fine, almost imperceptible trembling in his hands. He squeezed the stick tighter.

Tracer rounds reached out from the destroyer first—bright orange lines snapping through the air, reaching, probing. They were still too far. The shells fell short, throwing up spouts of water like miniature geysers. Splashes bracketed his path.

“Guns firing,” he said, more to anchor himself than to inform the others. “They see us.”

Of course they see us, idiot, he thought. That’s the point.

He had a clear shot at Coventry’s broad side now. Every instinct screamed at him to take it. Blow the big one apart. Kill the destroyer, the Sea Dart threat, the higher-profile ship. That had been the plan: Coventry first, then Broadsword if they were still alive.

But war had a way of laughing at plans.

The first shells walked closer. A line of white splashes stepped toward him, each one a geyser of water and shrapnel. Bullets ricocheted off the ocean surface, snapping past like invisible hornets. The heavy boom of Coventry’s main 4.5-inch gun rolled across the water, chased by the higher chatter of smaller-caliber weapons.

He saw a line of tracers suddenly rise, almost as if they had guessed his exact flight path.

They’re dialing us in, he thought. A few more seconds and they’ll cut us in half.

He looked past Coventry, saw Broadsword beyond her—smaller, less heavily armed. Slightly off to the side, almost presenting her full length without as much fire coming his way.

He made the decision in the blink of an eye—and his wingman trusted him enough not to question it.

“Change target!” he called. “Go for the frigate. Break to port. Now!”

He yanked the stick left and felt the G-forces claw at his body as the A-4 rolled and banked. His stomach lurched. The sea tilted to fill his canopy. Coventry’s tracers swept past his previous path, reaching for the empty air his jet had occupied half a second earlier.

Rinke followed, roaring just behind him.

For a moment, as they flashed past Coventry’s bow, Pablo could see men on her deck. Tiny figures, some firing rifles at him, others just staring, faces turned up like spectators at some monstrous air show.

He could have reached out and touched their ship.

Broadsword loomed ahead now, directly in his sights. Smaller, yes, but still deadly. Somewhere within her steel skin, the Sea Wolf system was whirring to life, computers rebooting, radars turning.

“Azul Uno, attack now!” he shouted.

He lined up the ship’s middle in his crosshairs and squeezed the bomb-release button.

The Skyhawk jolted as two 1,000-pound bombs fell away from his pylons. His jet surged upwards slightly, lighter, freed from the burden.

He kept low, holding his course for a heartbeat longer than his instincts wanted, then yanked the stick and banked away to avoid slamming into the frigate’s superstructure.

Behind and beneath him, the bombs hit the sea at a shallow angle.

The water did something strange then—something no training film had ever quite prepared him for. The bombs skipped.

They plunged in, then burst back out, skipping across the surface like monstrous stones thrown by some gigantic child. Each skip sent up a plume of water.

On Broadsword, sailors watched in something beyond terror and beyond fascination as the bombs bounded toward them. One disappeared into a wall of spray and never came up again.

The other hit the ship.

Steel rang like a bell as the bomb punched through the hull, screaming into the innards of Broadsword. It tore its way upward, kinetic energy carrying it like a bat out of hell. It punched up through the deck, tearing open metal and throwing splinters of steel and debris into the air, then flew on, tumbling end over end before dropping into the sea on the far side.

And then… nothing.

No explosion. No fireball.

The bomb sank quietly into the depths, as if embarrassed by its own failure.

Pablo saw nothing of this in detail; he caught only glimpses. A flash of metal, a brief puff of smoke, sailors diving for cover. Then he was past, heart in his throat, every muscle rigid.

“Impact!” Rinke shouted over the radio. “But no detonation! Dios, it went right through her!”

Pablo let out a breath he hadn’t realized he’d been holding. Relief and frustration tangled in his chest.

“We’ve done some damage,” he said. “But not enough. Get your head back in the game. This isn’t over.”

He banked, climbing a little—not enough to poke his head too far above the radar horizon, but enough to get a sense of the battlefield.

Behind them, Broadsword was trailing smoke, her deck scarred. Coventry still steamed nearby, guns searching for new targets. Neither ship was sinking.

And the second section—Velasco and Barrionuevo—was still inbound.

On Coventry’s operations room, it had taken only seconds for hope to sour.

“Sea Wolf reports malfunction,” came the grim report over the link.

Hart-Dyke’s jaw clenched.

“What kind of malfunction?” he demanded.

“Guidance system crashed when the contacts split, sir,” the liaison officer replied. “They were tracked as a single target at first. When it separated into two, the coordinates fed into the system conflicted and… it froze.”

“Can they reboot?” he asked, already fearing the answer.

“Broadsword is attempting a restart.”

Hart-Dyke could imagine the scene in the frigate’s own operations room—men hammering at console keys, controllers swearing under their breath, furious at a machine that couldn’t match the speed of events outside its circuits.

Technology, he thought bitterly, is wonderful when it works.

He had counted on Sea Wolf to protect them if the Sea Darts failed. And the Sea Darts hadn’t even gotten a clean shot yet.

Now, reports were coming in from the lookout posts.

“Bombs skipped over Broadsword and inboard, sir. One went through her hull but didn’t explode. Damage, but she’s afloat.”

It was a minor miracle. A miracle paid for by defects in Argentine fusing and rushed bomb preparation.

Hart-Dyke took that miracle and stored it away. He knew they couldn’t keep spending luck like this.

“Any further contacts?” he asked, turning back to the radar display.

“Yes, sir. Four total. Two just attacked Broadsword, two more approaching from behind Pebble Island. Range twenty miles and closing.”

The captain’s shoulders stiffened.

“New section,” he said quietly. “Second wave.”

This time, there would be no element of surprise. Coventry and Broadsword both knew the threat was out there. Sea Dart crews scrambled to adjust, to find new angles. Men in the radar rooms tuned their scopes, fighting sea clutter.

Hart-Dyke made a decision.

“Turn to starboard,” he ordered. “Bring Coventry’s bow toward them. I want the best possible shot with Sea Dart.”

As the big destroyer began to turn, engines answering the helm, her long, sharp bow bit into the gray South Atlantic, throwing up spray.

Onboard Broadsword, officers working frantically to bring Sea Wolf back online watched in dismay as Coventry’s silhouette slid across their screens, directly in front of their firing arc.

“Coventry is blocking our line of fire!” one shouted.

“Signal them to clear the line,” Broadsword’s captain ordered.

But there was no time.

The second pair of Skyhawks ripped across the sea like angry arrows.

First Lieutenant Mariano Ángel Velasco felt sweat trickle down his back beneath his flight suit. It had nowhere to go; the cockpit was a sealed bubble of noise and vibration and expectation.

He had heard the radio chatter. He knew Carballo’s section had made it through the first gauntlet, had struck Broadsword and somehow survived a dance with death. He also knew their bombs had failed to explode properly.

Now it was his turn.

He had different bombs—250-kilogram ones, smaller but with fuses considered more reliable. Less glory per unit, maybe, but greater odds of actually going off.

“Azul Tres to Azul Uno,” Velasco said. “We’re five miles back. We see your smoke. Are you intact?”

“We’re scratched but still flying,” Pablo replied. There was fatigue in his voice, and something else—an electric, brittle tension. “They’re alert now. Coventry is turning to meet you. Broadsword is hurt but still alive.”

“Roger,” Velasco said. “We’ll finish the job.”

He wondered, as he often did in the quiet moments between maneuvers, if anyone on those ships had families. Wives. Children. Parents waiting at home. He imagined some English mother on the other side of the world listening to the BBC, straining to hear her son’s ship named among the safe ones.

He shoved the thought away. If he let himself dwell on that, he knew, his hand might tremble at the wrong moment.

The sea blurred beneath him. Whitecaps became streaks. Air pressure pressed at his ears.

“Four miles,” Barrionuevo reported, his voice as flat and steady as ever. “We have visual on the destroyer.”

Velasco saw Coventry now, a gray triangle slicing through the water, her radar arrays and masts etched black against the low sky. Smoke drifted from behind her, maybe from Broadsword, maybe from her own guns.

On Coventry, missile operators finally got what they had been waiting for—a solid lock.

“Sea Dart has target,” the director called. “Hostile at fifteen miles, low level but within engagement parameters. Firing solution computed.”

“Shoot,” Hart-Dyke said.

On the destroyer’s foredeck, the twin-armed launcher jerked and then swung upward with a mechanical grace. One of the sleek white missiles leapt from its rail in a sudden burst of fire and smoke, leaving a trail of white exhaust as it roared out toward the oncoming jets.

In Velasco’s cockpit, the world flashed briefly brighter in his peripheral vision. He turned his head just in time to see a white streak carve the air to his right, climbing slightly, then arcing.

Instinct pulled at him. Climb. Break. Evasive maneuvers.

But climbing would mean rising into the band where the radar could see him perfectly. It would mean giving Sea Dart exactly the kind of target it had been born to kill.

He forced the instinct down, like pushing a scream back into his chest.

“Stay low,” he told Barrionuevo. “Lower than you think is sane.”

The missile, robbed of a clear radar return, flew on straight, searching with blind electronic eyes for a target that had abruptly ducked out of sight. Without solid tracking data, its guidance struggled, then lost coherence entirely. Instead of curving in toward the jets, it simply streaked past and continued out over the empty ocean.

Velasco watched it pass about five hundred meters to his right, leaving a long, fading scar across the gray.

“Missile overshoot,” he said, voice tight. “They wasted their shot.”

On Coventry, groans of dismay rippled through the operations room. The missile’s track on the display went erratic, then straight, then off the screen.

“Negative hit,” the missile officer said.

Hart-Dyke’s jaw clenched. That had been their best, maybe only, chance to intercept the incoming attackers at range. Now the burden fell squarely on close-in guns—and on Broadsword’s Sea Wolf.

Which, at that moment, was still fighting a battle with its own software.

“Sea Wolf is back online,” came the breathless call from Broadsword. “We have lock on two incoming aircraft.”

In the frigate’s operations room, the Sea Wolf display finally bloomed with coherent tracks. The system locked onto the low-flying Skyhawks, interpreting them as small, fast-moving targets—its specialty. The launcher slewed, ready to fire.

Then Coventry, in her effort to maneuver for a better Sea Dart shot, turned directly across Broadsword’s line of sight.

On the radar screen, a larger mass of steel and moving metal suddenly interposed itself between Broadsword’s launcher and the Skyhawks.

“Coventry is masking our firing arc!” an operator shouted. “We can’t engage!”

“Signal Coventry to clear the line!” Broadsword’s captain barked. “Now!”

But there was no way to move 4,800 tons of destroyer quickly enough. What could be done in seconds in a flight simulator took much longer when it meant shifting hundreds of feet of steel and machinery through real water.

By the time Coventry could have moved clear, it would be too late.

Velasco felt the Coventry grow larger in his canopy, her gray hull filling more and more of his forward view.

Tracer fire reached out at him now in thick, glowing curtains. The destroyer’s main gun pounded the sea around him, sending up towers of water. Smaller-caliber cannons and machine guns stitched arcs of fire across the air, chasing his flight path.

He saw one of the smaller guns suddenly go quiet, its barrel locking at an awkward angle. Jamming under stress. Good.

He heard Carballo’s voice in his head, from some long-ago training session.

Don’t look at the tracers. Look at where you want to go. Fear follows your eyes.

He kept his gaze locked on a point just below Coventry’s bridge, slightly forward of midships. He wanted the bombs to hit there, near the heart of the ship, where radar rooms and brains and nerves were wrapped in steel.

“Barrionuevo, you still with me?” he asked.

“Right behind you,” came the answer. “I’ll drop when you do.”

The distance collapsed.

On Coventry, the call went out over the ship’s loudspeakers.

“Brace! Brace! Brace!”

Men dove for deck, hands over their heads. In compartments below, sailors grabbed whatever they could—pipes, bunks, each other—and braced themselves for impact.

Hart-Dyke gripped the edge of the operations table so hard his knuckles went white. The world around him seemed to slow.

Velasco’s aircraft roared across the last few hundred yards.

He thumbed the cannon trigger first.

His A-4’s twin 20mm cannons spit fire, a blazing stream of shells lacing across Coventry’s deck and superstructure. Metal sparked, antennas shattered, sheets of steel splintered under the hammering impacts. Men on deck threw themselves flat as bullets stitched the air above them.

He held the trigger down until he was almost on top of the target, then released.

His thumb found the bomb-release button. He pressed.

The jet jerked slightly lighter. The bombs fell away, tumbling for a heartbeat and then stabilizing, noses down, fins biting the air.

He kept flying straight for an instant that felt like an eternity, unwilling to break too soon and risk swinging his bombs off target. Then he hauled back on the stick, banking away, the G-forces squeezing him, his teeth grinding.

Behind him, Barrionuevo’s Skyhawk screamed over the ship—but when he hit his own release, nothing happened. His bombs stayed stubbornly strapped to his wings.

“Damn it!” Barrionuevo shouted. “Release failure!”

In Coventry’s operations room, there was a deep, metallic thud that could be felt more than heard. Then another. Two hollow impacts, like giant fists punching through the hull.

For a second, nothing else happened.

In that stretched-out, impossible moment, men started to get up. Dust and fragments fell from overhead. Someone shouted over the internal net.

“Bridge, Damage Control. We’ve—”

The voice cut off.

The bombs detonated.

The explosions didn’t sound like the movies.

There was no single, clean boom. There was a shattering, ripping convulsion that tore the world in half.

One bomb exploded under Coventry’s bridge, blowing a great jagged hole in the side of the ship. The blast ripped through compartments, shredding bulkheads, turning equipment into shrapnel. In the operations room, consoles were flung aside, panels torn from their mounts. Men were hurled off their feet.

The radar scopes went dark. The computer room ceased to exist as anything recognizable. Smoke and flame poured through the corridors.

The second bomb detonated in the forward engine room.

The shockwave tore through the space, smashing gauges, rupturing pipes, snapping cables like threads. The explosion ripped through fuel lines and electrical conduits. Lights went out in a chain, like someone had dragged a black cloth down a corridor of bulbs.

Somewhere deep in Coventry’s hull, a main cable trunk came apart with the sound of giant bones breaking.

The ship shuddered, a deep, awful vibration that ran through her from stern to bow. Her forward momentum faltered. Engines died. The humming, ever-present vibration of machinery that had been the background of every sailor’s life aboard simply… stopped.

Silence, broken only by the groan of stressed metal and the roar of rushing water.

Hart-Dyke lay on his side amid twisted wreckage. His ears rang. His nose was full of the smell of burning insulation and hot metal. A pressure weighed on his chest.

He blinked, trying to clear the blur from his vision. The operations room was unrecognizable. Consoles were crushed, some hanging at odd angles. Smoke filled the space, thick and choking.

Someone was screaming.

No, several people were screaming.

He tried to push himself up and hissed in pain. A piece of metal had sliced across his side. His uniform was wet with blood.

For a moment, he didn’t know his own name.

Then training, habit, and stubbornness surged back.

He was the captain. This was his ship. This was his responsibility.

He forced himself onto his knees, then his feet, using a bent console for support. The world swayed strangely beneath him. Coventry was listing.

He reached for the intercom panel by reflex. The microphone dangled from melted wiring. He lifted it and tried anyway.

“Bridge… this is Ops…” he rasped. “Report… status…”

Nothing. Not even static.

The internal comms were dead.

Smoke thickened, rolling in dark clouds across the ceiling. Somewhere nearby, a small fire crackled.

He knew that staying in this compartment meant dying.

“Everyone who can move, get out!” he shouted, his voice stronger now. “Now! Leave the wounded to damage control. We have to get to the upper deck.”

A few faces turned toward him, eyes red from smoke. Some were bleeding. Some were wrapped in shock. But his voice cut through the panic, gave them something to move toward.

They staggered out, pushing through debris, stepping over bodies that didn’t move.

The corridors were barely better. The ship groaned with a sickening sound, like an injured animal. The list was more pronounced now; the deck slanted under his feet, pulling him toward the low side.

Water, he thought. We’re taking on water. Forward compartments, maybe more.

He thought of the damage-control teams, of men in heavy suits, helmets strapped on, rushing with hoses and extinguishers into smoke-filled spaces. Fighting fire and flood at the same time. Heroes whose names almost no one would remember.

He found a ladder, its metal warm from nearby fire. He pulled himself upward, each rung a small victory, his side burning with each movement. Men followed behind him. At least a few, he thought. Enough.

He emerged onto the open deck, into cold, fresh air that stung his lungs. For a moment, the sky seemed too big.

Coventry’s deck was canted at an alarming angle. The horizon looked wrong. Smoke poured from torn sections of the superstructure. Here and there, flame licked out, tasting oxygen before damage-control teams slapped it back with foam and water.

He looked toward the water. Broadsword had circled around, closer now, her own scars visible, but very much alive. British helicopters beat the air above, already vectoring in. Rescue birds.

On Coventry’s deck, he expected chaos. Men panicking, running, shouting.

Instead, he saw something else.

Order.

Teams of sailors were moving with practiced efficiency, dragging wounded shipmates out of hatchways and onto the listing deck. Others were assembling life rafts, inflating them, checking lines. A few were manning hoses, directing streams of water at the worst of the flames.

Someone had already sounded the abandon-ship order over portable loudhailers. He could hear it echoing.

“Abandon ship! Abandon ship! Move to your emergency stations. Take only what you need to survive!”

A young seaman saw him and ran over, eyes wide.

“Captain! Are you all right, sir? You’re bleeding.”

Hart-Dyke looked down. His uniform was torn, stained red.

“I’ve been better,” he said dryly. “What’s our situation?”

“Forward compartments are flooded, sir,” the seaman said, trying to keep his voice level. “We’ve lost all power. She’s going over fast. Damage control says… says we can’t save her.”

Hart-Dyke looked down the length of the ship. Coventry’s bow was already dipping, her stern rising just a fraction. The list was worsing by the minute.

He felt a painful compression in his chest that had nothing to do with his injury.

She was his ship. His command. A steel city that had been home to hundreds of men. She had carried them through rough seas and quiet watches, through boredom and terror. He had known this might happen—everyone did—but knowing and seeing were different things.

He swallowed.

“Very well,” he said. “Get the men off. Prioritize the wounded and those below decks. Nobody gets left behind if we can help it.”

He walked along the slanting deck, sometimes needing to grab onto railings or fittings to keep his footing. Men saluted him as he passed, even in the chaos.

“Carry on,” he told them. “Get your mates off this ship.”

Someone tried to steer him toward a waiting life raft.

“Captain, you should get off too,” a petty officer said.

“Not yet,” Hart-Dyke replied.

The petty officer hesitated only a second, then nodded. Sailors, he thought, were good at recognizing when an order wasn’t really an order but something deeper.

One by one, rafts hit the water, bright orange dots against the cold, steel-gray sea. Men slid down ropes or jumped, some clutching onto lifejackets, some helping wounded comrades.

A scream cut through the air as a man slipped and went over harder than planned, hitting the water badly. Two others immediately dove in after him, hauling him toward a raft.

Broadsword moved closer, her crew lining the rails, ready to pull survivors aboard. Helicopters hovered, dropping rescue swimmers, their rotors chopping the air into thunder.

Coventry groaned again, louder this time. The list increased. Water poured over her low side, beginning to flood the upper deck.

“Captain, that’s the last of the organized parties,” his first lieutenant said, appearing beside him, face soot-streaked. “Most of the wounded are off. Some are still unaccounted for below, but damage control says it’s… it’s not accessible anymore. We’d lose anyone we send.”

Hart-Dyke’s shoulders sagged for a heartbeat. He hated leaving his men, any man, behind. But he knew what compartments sealed and flooded meant in this kind of fight. He had seen photos of other ships, other wars.

He nodded, face grim.

“Very well,” he said. “You go now, Number One.”

“Sir—”

“That’s an order,” he snapped, the captain again. “Get in a raft. Help organize the survivors. They’re going to need someone who isn’t dizzy and bleeding.”

The lieutenant hesitated, then saluted.

“Aye, sir. See you on Broadsword.”

Hart-Dyke watched him climb into a raft with others and drop away toward the sea.

He stood alone on the tilting deck for a long moment, breathing in smoke and cold air. The wind had picked up, smearing the edges of the rising smoke into ragged trails. The South Atlantic looked impassive, indifferent.

He looked down at the water, at the rafts, at the men bobbing there in their bright survival suits, huddled together, looking up at him.

He looked toward Broadsword. She was closer now, slowing to recover more survivors, her own crew already hauling men out of the waves.

Coventry’s bow dipped further. The angle of the deck grew worse. The railing he had been leaning on was almost horizontal.

Time.

He took one last look around his command. The twisted wreckage, the scarred paint, the smoke rising like a funeral pyre. Every scuff on the deck had a story. Every cabin door led to a life that had been lived here.

He thought of his family at home, of what the Admiralty would tell them. He thought, strangely, of the Argentine pilots who had done this. Men like him, serving their country, flying old jets on the ragged edge of possibility.

War was idiotic, he thought. Glorious for politicians, hell for professionals.

He walked to the edge of the deck, where a final raft hung waiting, half in the water, half still attached. A petty officer in the raft reached up, hand outstretched.

“Sir!” he called. “Come on!”

Hart-Dyke paused, then nodded.

“All right,” he said. “Let’s go.”

He slid down, gripping the rope, dropping with a jolt into the raft. A knife flashed as someone cut the tether line, and the raft drifted away, carried by the swell.

From the water, he watched his ship die.

Coventry rolled slowly onto her side, hull lifting, propellers briefly visible, glistening and alien. Bubbles frothed along her length as trapped air rushed out. Then, in a motion almost graceful, she slipped beneath the surface, the sea opening to swallow her whole.

Within twenty minutes of the bombs hitting, HMS Coventry was gone.

The Skyhawks were already miles away, low and fast, engines thundering, when Coventry sank.

Pablo and Rinke flew in strained silence, each trapped in his own thoughts, watching fuel gauges and engine temperatures, eyes sweeping the sky for pursuing Harriers or missiles that never came.

Behind them, Velasco and Barrionuevo rejoined, their jets battered but intact.

“Report,” Pablo said.

“Bombs on target,” Velasco replied. His voice trembled just a little. “She’s hurt bad, Pablo. Fires everywhere. I saw explosions near the bridge and amidships.”

“Any secondary explosions?” Rinke asked. “Magazine?”

“Hard to tell. A lot of smoke. But she was listing before I broke away.”

No one spoke for a few seconds.

“Good work,” Pablo said finally, the words tasting oddly dry. “Now let’s get home before their fighters find us.”

They flew on, hugging the waves, South Atlantic spray kissing their bellies, aircraft leaving long, faint trails of disturbed air behind them.

Only when the coastline of Argentina finally came into view again, low and familiar, did Pablo feel his shoulders begin to unclench.

He brought his A-4 in to land, the runway rising to meet him, concrete a comforting solid thing beneath his wheels. He taxied slowly, canopy still down, breathing the thinning aroma of fuel.

When he opened the canopy, cold air hit his face. The sound of the engine faded as he shut down, leaving only the excited shouts of ground crews and the distant chop of other aircraft.

He climbed down stiffly. His legs shook a little when his boots hit the tarmac.

Someone thrust a hand out to him. A mechanic, eyes luminous.

“Capitán, they say you hit them!” the man said. “Radio intercepts—one of the ships is sinking! The destroyer!”

Pablo blinked.

“The destroyer?” he repeated.

“HMS Coventry,” someone else said. “They say she’s gone.”

Rinke whooped, slapping Pablo on the back so hard he almost stumbled.

“Did you hear that, Pablo? We sank a bloody destroyer!” he shouted. “With these old crates and iron bombs!”

Velasco and Barrionuevo climbed down from their own aircraft nearby, ground crew swarming them with questions, claps on the shoulder, cigarettes thrust into their hands.

Velasco allowed himself a small, shaky smile. His hands were still trembling, and when he tried to light the cigarette, the match broke. Barrionuevo took it from him, lit it, and handed it back with a nod.

“Buen trabajo,” Barrionuevo said quietly. “We did what we came to do.”

Officers emerged from the operations building, some already knowing, some asking for details.

“What altitude did you run in at?”

“How close did the Sea Darts get?”

“Did Sea Wolf fire?”

“How many hits did you see?”

Pablo answered as best he could, drawing diagrams in the air with his hands, using the edge of the runway as a stand-in for a British ship.

But even as he spoke, a strange heaviness settled in his chest.

He had done his duty. He had flown low, ridden the line between skill and suicide, dropped his bombs on enemy ships. He had lost no men—not today. Every Argentine pilot on the mission had returned.

Nineteen British sailors, he would later learn, had not.

He thought of them as the sun began to lower, casting long shadows across the base. Men were laughing, cheering, slapping each other’s backs. Radios carried breathless news reports. Politicians in Buenos Aires would no doubt trumpet a great victory.

He walked away quietly, past a stack of ordnance, into the shadow of a hangar.

He leaned against the cool metal, closed his eyes, and let the sounds of celebration wash over him, muffled.

He saw again the image that had stayed with him most strongly: not the explosion, not the impact, but the brief flash of faces on Coventry’s deck as he screamed past. Men in blue coveralls, shocked, determined, terrified. Not so different from his own.

He wondered if somewhere, right now, their families felt something. A chill. A tremor. A sudden heaviness in the heart.

War had turned them all into targets and statistics. But those men had names and stories, too.

He heard footsteps beside him. It was Velasco, cigarette hanging from his lip, helmet under his arm.

“Thinking too much again?” Velasco asked.

“Maybe,” Pablo said.

“If you don’t, you’re not human,” Velasco replied. “If you do, you’re not a very good fighter pilot.”

Pablo let out a short, humorless laugh.

“That’s a nice paradox,” he said.

Velasco shrugged.

“My father used to say, ‘You can’t carry all the ghosts, hijo. Just the ones that belong to you.’” He took a drag, exhaled. “We did our job today. We hit a warship that was attacking our forces. We survived. That’s all we can control.”

“And the rest?” Pablo asked.

“The rest belongs to history,” Velasco said.

He was right, of course. In the weeks to come, the war would grind on. The British, shaken but not broken, would continue their advance. They would retake the islands with grit, training, and grim determination. Argentine forces, brave but outmatched, would eventually surrender. Flags would change. Maps would be redrawn—or rather, returned to their previous colors.

But the day Coventry went down would remain etched in both countries’ memories, a moment of intense courage and cruel luck on both sides.

In Britain, the story would be told of sailors who fought to save their ship and each other, of a captain who was the last to leave his sinking command, of a frigate trying desperately to protect her consort with a system that failed at the worst moment.

In Argentina, the story would be told of pilots who flew ancient jets at wave-top height through storms of fire to strike at a superior navy, of missions that were statistically suicidal and yet somehow succeeded, of bombs that either failed or worked with terrifying finality.

Years later, some of those men would meet. A British officer and an Argentine pilot, shaking hands over a shared history, talking about that day with a mixture of pride and sadness. They would swap stories, compare perspectives, marvel at the coincidences and misfires that had turned a handful of decisions into life and death.

They would agree on one thing above all: that war was a wasteful, brutal teacher.

On a quiet evening years after the conflict, in a small house far from the sea, an older Pablo would sit at a table, tracing his finger along a faded newspaper clipping about the Falklands War. The picture showed HMS Coventry, still upright, cutting through a calm sea under a cloudy sky.

His daughter, now grown, would walk past, pause, and look over his shoulder.

“Was that the ship from your stories?” she would ask, nodding toward the photograph.

“Yes,” he would say.

“And you were in one of the planes that attacked it?”

“Yes.”

She would be silent for a moment, thinking.

“Did you hate them?” she would ask.

Pablo would stare at the picture. At the neat rows of portholes, the clean lines of the deck, the flags fluttering in a wind he could almost feel.

“No,” he would say, after a long pause. “I was afraid of them. I wanted to defeat them. But I didn’t hate the men on that ship. They were like us. Doing what they were ordered to do. Doing what they believed they had to.”

His daughter would frown a little.

“Then why did you…?”

“Because if I didn’t,” he would say quietly, “their bombs would fall on our men on the islands. On boys with rifles and little training. On ships with other fathers and sons. In war, it is always someone else’s turn in the crosshairs.”

She would nod slowly, not fully understanding, maybe never able to. That, he would think, was a blessing.

He would reach up and touch the tiny sun sticker still hidden under the canopy sill in his memory—long peeled away in reality, but vivid in his mind.

He had not gotten lost in the clouds that day. He had found the enemy instead.

And in that finding, he had lost something else—some naive belief that skill and bravery alone could keep death at bay, that war could be clean, surgical, precise.

When survivors of Coventry gathered at reunions, they would raise glasses to absent friends and tell stories that slid between gallows humor and quiet grief. They would talk about the young seaman who always stole extra pudding from the galley, the petty officer who could fix anything with duct tape and profanity, the officer who always mixed up port and starboard when he was tired.

They would talk about the smoke, the noise, the way the deck suddenly tilted. They would talk about the captain, wounded and bloody, insisting on staying on deck until everyone else was off.

Some nights, in their sleep, they would still hear the hollow thunks of the bombs hitting, still feel the eerie, suspended moment before the explosions came.

On the other side of the ocean, Argentine pilots would gather in their own reunions, raising glasses to compañeros who never came back from other missions. They would tell stories about jammed bomb racks, about flying so low the salt spray left crusts on their goggles, about getting home with fuel gauges reading zero and engines coughing.

They would laugh about the time someone nearly forgot to raise his landing gear, about pranks in the mess hall, about the gravel-voiced instructor who’d told them all that flying was just “falling in a controlled manner.”

And when they talked about May 25, 1982, there would be a hush. Then someone would imitate the way the bomb had skipped like a stone, or the pilot who’d yelled “Goal!” over the radio when Coventry exploded.

They would laugh, because humor was a shield, but behind it there would be something else in their eyes.

Respect, maybe. For the men they had fought. For the thin line between survival and a name engraved on a memorial plaque.

In the end, the sinking of HMS Coventry by A-4 Skyhawks was not just a tale of victory or defeat. It was a story of human beings pushed to the edge of their skills and courage, grappling with machines and decisions in seconds that historians would analyze for decades.

It was the story of old jets and new missiles, of landlubbing politicians and seafaring professionals, of maps and flags and the cold, indifferent sea that swallowed steel without caring who painted it.

And it was the story of a day when four small attack jets, flown by men who had once been boys dreaming of flight, came screaming in low over gray waves—and changed the lives of everyone aboard two British warships in less than ten minutes.

When the Skyhawks sank the British destroyer, they also sank a little further into the shared, complicated memory of two nations. Not as heroes or villains alone, but as men caught in the slipstream of history, doing their jobs in a storm they hadn’t made, under skies that belonged to no one.

Historical sources:

Report of the Board of Inquiry into the loss of HMS Coventry 25th May 1982. National Archives DEFE 69/1336

25th May 1982 by Damien Burke, at https://www.hmscoventry.co.uk/d118/25…

Halcones de Malvinas by Pablo Marcos Rafael Carballo (2 ed.)

Documentary Sea Of Fire by BBC (2007) based on the book by David Hart Dyke. Four Weeks in May: The Loss of “HMS Coventry”

memorial sites hmscoventry.co.uk and hmsbroadsword.co.uk

News

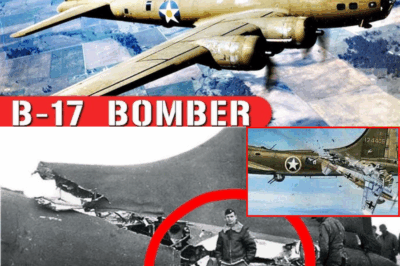

CH2. Was the B-17 Flying Fortress a Legend — or a Flying Coffin? – 124 Disturbing Facts

Was the B-17 Flying Fortress a Legend — or a Flying Coffin? – 124 Disturbing Facts In this powerful World…

CH2. When a BF-109 spared a B-17

December 20th 1943, a badly shot up B-17 struggled to stay in the air, at the controls Charlie Brown. Passing…

CH2. How One Plane Changed the War in 1944

The Grumman F6F Hellcat was America’s answer to Japan’s deadly Zero — and it didn’t just win, it dominated. From…

HOA Kept Parking Her Porsche Across My Driveway—So I Returned the Favor… Piece by Piece

HOA Kept Parking Her Porsche Across My Driveway—So I Returned the Favor… Piece by Piece Part 1 The shriek…

Dad Slapped Me & Cut Me From $230M Will — Then Lawyers Revealed I Was KIDNAPPED As A Baby

Dad Slapped Me & Cut Me From $230M Will — Then Lawyers Revealed I Was KIDNAPPED As A Baby” At…

My DAD Beat Me B.l.o.o.d.y Over A Mortgage—My Sister Blamed Me. I Collapsed Begging. Even Cops Shook…

My DAD Beat Me Bloody Over A Mortgage—My Sister Blamed Me. I Collapsed Begging. Even Cops Shook… When my dad…

End of content

No more pages to load