What Happened to the Luftwaffe Planes After WW2?

The hangar doors groaned like something wounded.

Lieutenant Jack Morrison pressed his shoulder into cold steel and shoved, boots slipping on broken glass and oil. For a heartbeat, it felt like the war was still alive, resisting the touch of an American hand. Then the rusted rollers screamed, and the door lurched open, spilling a shaft of gray Bavarian light across the concrete floor.

The breath caught in his throat.

They were everywhere.

Sleek, predatory silhouettes stretched off into the dimness—wings like knives, noses sharp as bullets, twin engines hanging under swept-back wings. Some still had fuel hoses dangling from their bellies. A few had ladders leaning against them, as if their ground crews had just stepped away for a cigarette.

“Jesus,” someone whispered behind him. “They just walked away.”

Jack stepped forward, the sound of his boots echoing in the cavernous hangar. He’d flown P-51s over Germany for the last year, watched B-17s burn against the sky, seen the Luftwaffe as flashes of wings and tracers and sudden, screaming death. But he’d never seen anything like this.

The nearest jet sat low and dangerous, paint still glossy under a film of dust. Faded black crosses on its fuselage, a wicked swept wing, twin engines that looked like they’d been ripped from the future.

“Messerschmitt Me 262,” a calm voice behind him said. “Schwalbe. The Swallow.”

Jack turned. The man who’d spoken wore the same uniform as the rest of the German prisoners in the yard, but he carried himself differently. Straight-backed, hands behind his back, eyes cool and distant. There was still something of the cockpit in him.

“And you are?” Jack asked.

“Hermann Heinz Brauer,” the man replied in careful English. “Luftwaffe. I flew these.”

He said it without pride, without shame. Just a fact, laid on the table like a deck of cards.

An American captain pushed past Jack, clipboard in hand, eyes hungry. “This is Lechfeld, right? Near Augsburg? Intel said there were jets here, but…” He whistled softly. “Nine of them. Nine flyable 262s.”

Jack tore his eyes away from the planes to look back out at the airfield. Beyond this hangar, more concrete caves waited, doors still shut. The war in Europe had officially ended yesterday—May 8th, 1945—but the sense of urgency hadn’t. Not for the men who’d been sent here with orders that felt stranger than anything they’d done before.

The captain snapped the clipboard closed and turned to Brauer. “You flew them. Good. You’ve got a choice. Prison camp, or you help us fly these to France.”

Brauer considered this for only a second. “I prefer to fly.”

Jack watched the small exchange with a growing sense of unreality. The last time he’d seen a 262, it had been streaking past his Mustang like a hawk through a flock of sparrows. Now they were here, lined up in cold silence. And one of the men who had hunted them was about to become his… instructor?

The captain turned to Jack. “Morrison, you’re with Watson’s group now.”

“Watson’s—sir?”

“Colonel Harold Watson. Operation Lusty. We’re collecting every advanced German aircraft we can get our hands on. Jets, rocket jobs, weird prototypes. We’re flying them out before the Russians or the Brits grab them.” The captain’s grin was humorless. “Congratulations, Lieutenant. You’re a guinea pig now.”

Jack looked back at the Me 262. The future stared back.

He swallowed. “Yes, sir.”

Across Europe, in a hundred other hangars and fields from Denmark to Austria, other doors were being forced open, other men were standing very still, trying to make sense of scenes that didn’t fit the word “defeated.”

American infantrymen walked through forests where aircraft squatted under camouflage netting, their engines still warm. British soldiers marched past rows of Focke-Wulf 190s lined up wingtip to wingtip like toy soldiers, each one factory-fresh, never flown in anger. In Norway and Denmark, fighters sat in revetments with fuel in their tanks, waiting for orders that would never arrive. In Czechoslovakia, warehouses groaned under the weight of crated airframes and engine parts, production lines frozen mid-step as the Third Reich collapsed overnight.

This wasn’t 1918. It wasn’t a few hundred flimsy biplanes waiting to be scrapped.

These were jets. Rocket interceptors. Night fighters with radar sets that made Allied equipment look like children’s toys. They were the sharpest teeth German engineering could grow, and they were scattered across a continent that had just stopped burning.

Every major power looked at them and saw the same thing.

Not trophies.

Not relics.

A head start.

They called themselves Watson’s Whizzers.

The first time Jack heard the name, he thought it was a joke. A bunch of pilots drafted into some oddball technical unit, poking around enemy hardware while the rest of the Army figured out what to do with itself now that the shooting had (mostly) stopped.

Then he met Colonel Harold Watson.

Watson was compact, composed, the kind of man who seemed to vibrate with controlled energy. He’d been a test pilot at Wright Field before the war, the place where the Army tested everything with wings. Now he stood in a makeshift office in a commandeered German building, his desk an overturned packing crate, a hand-drawn map of Germany on the wall behind him. Colored pins marked airfields, factories, and unexplored dots that might yet hold miracles—or nothing.

“Gentlemen,” he said, looking over the line of pilots standing at attention. “You’ve been picked because you can fly anything and because you don’t scare easy.”

Jack wasn’t entirely sure about the second part.

Watson tapped the map with a pencil. “The Pentagon realized something too late for comfort. We underestimated German aviation by years. These jets, the radar-equipped night fighters, the swept wings—this isn’t theory. These aircraft fought us. And while we were catching up, the Soviets were watching too. Right now they’re loading whatever they find onto trains and hauling it east.”

He flicked the pencil from Lechfeld to a smear of red pencil across eastern Germany and Poland.

“Two weeks before Germany surrendered, we kicked off Operation Lusty. Luftwaffe Secret Technology. Our mission is simple. Find every advanced German aircraft that’s still standing. Secure it before anyone else does. Fly it to a port. Put it on a ship. Get it to the States.” He smiled thinly. “There are thirty-two other Allied intelligence teams after the same prizes. The Soviets don’t always ask. The British and French are… competitive.”

Someone chuckled nervously.

“You will be flying jets you’ve never flown, designed by people who were trying to kill you last month,” Watson went on. “You’ll be taking off from bomb-cratered runways with minimal maintenance. You’ll be trusting German manuals, German engineers, and German test pilots.”

He let that hang.

“If that bothers you,” he added, “say so now, and I’ll send you to a nice, safe clerical job in Paris.”

No one moved.

Jack’s stomach knotted, but he felt something winding up inside him too. P-51s had been the pinnacle of propeller-driven fighters, the best he’d ever imagined he’d touch. Now they were talking about leaving propellers behind entirely—flying into a world of pure jet thrust and shrieking engines. Terrifying. Irresistible.

Their first lesson in the future began on a gray June morning.

The Me 262 sat on the Lechfeld runway, its nose pointed toward a line of bomb-shattered hangars. Jack walked around it with Brauer at his side, the German pilot’s hands moving with practiced ease as he pointed to intakes, trailing edges, hatches.

“You must understand,” Brauer said, “the engines are… how do you say… temperamental. You cannot move the throttle quickly. Not like with your Mustangs. Gentle. Always gentle. If you slam it forward, it will flame out. Or worse.”

“Worse?” Jack asked.

Brauer shrugged one shoulder. “Sometimes they come apart. Pieces of turbine through the fuselage, the wings. Through the pilot.”

“Oh,” Jack said faintly. “That kind of worse.”

Brauer actually smiled. “You will be fine if you respect it. She is fast. Faster than you imagine. But she is not forgiving.”

The cockpit was cramped compared to the Mustang’s, but the layout was oddly familiar—German dials and switches, different shapes and labels, but the same basic ideas. Altitude. Airspeed. Fuel. Engine instruments for each Jumo 004 jet mounted under the wings.

Jack ran his fingers over the throttle levers. Two. Not the single reassuring prop control he was used to, but twin metal handles that controlled machines that sucked air and fuel and turned it into screaming fire.

“Why are you helping us?” he asked, before he could stop himself.

Brauer paused, then climbed up onto the wing with him, looking out across the airfield. Rows of wrecked planes lay at the far end of the concrete, abandoned Bf 109s and Fw 190s, the once-feared backbone of the Luftwaffe now reduced to scrap awaiting the torch.

“Germany lost,” he said simply. “I flew for my country. Not for Hitler. At least, that is what I told myself. Now my country is ruins. My family… I do not know.”

He took a breath.

“If I go to a camp, I sit and wait and remember. If I fly, at least I am doing what I know. And there is a part of me that wants to see what happens to these machines. To know they do not just disappear under bulldozers.”

He looked at Jack with an expression Jack didn’t quite understand. “You want to know too. Otherwise you would not be here.”

Jack thought of all the friends he’d lost over the last year, of flak and tracers and the white spirals of parachutes that didn’t always open. Of the first time someone said the word “jet” on a radio channel, a panicked shout that something had just flown through their formation so fast no one could even get a bead on it.

“I want to make sure they never do this to us again,” Jack said.

Brauer nodded slowly. “Then we both have our reasons.”

The engines lit off with a strange, rising whine that crawled up Jack’s spine. This wasn’t the reassuring rumble of a Merlin; it was something rawer, thinner, like a giant dentist drill winding up toward some unholy frequency.

Brauer sat in the rear cockpit of a trainer version of the 262, his voice crackling in Jack’s headset. “Good. Good. Now watch the temperatures. Do not move the throttles too fast. Yes. Like that. Feel the delay? You ask, and she thinks about it, then answers.”

The runway ahead shimmered in the summer heat, the edges ragged with bomb craters and hastily filled potholes. At the far end, some American GI had parked a jeep as a makeshift marker.

“Ready?” Brauer asked.

“No,” Jack said honestly.

“Good. Only idiots are ready for their first jet.”

They rolled.

Acceleration was sluggish at first, the engines slow to spool, the sensation more like being pushed than pulled. Then, somewhere past the halfway mark, the thrust built and the Me 262 surged forward, pressing Jack back into his seat. The whine became a roar, the world narrowed to the strip of concrete ahead.

“Eighty… ninety… now,” Brauer said calmly. “Rotate.”

Jack eased the stick back. The nose lifted, the bumps of the runway vanished, and for a heartbeat he was sure they were going to settle back onto the shattered concrete and tear the landing gear off.

Instead, the airfield dropped away.

The climb was shallow but relentless, the airspeed indicator swinging around to numbers Jack had never seen so low to the ground. Two hundred. Three hundred. Four hundred.

He let out a shaky laugh he didn’t remember starting.

“This is insane,” he said.

“Schnell,” Brauer replied, the German word for fast sounding like a prayer. “Now you see why your bombers feared us.”

Across the ruins of the Reich, other men were discovering the same thing from a different angle.

A Soviet test pilot named Andrei Kokhetkov climbed into a captured Me 262 on a ragged airstrip in occupied Germany, controllers shouting in Russian instead of German, mechanics in Red Army uniforms swarming like ants around alien machinery. The tools were German, the technical manuals full of Gothic script and precise diagrams. The flag on the control tower was different.

“Remember,” one Soviet engineer called up to him in heavily-accented Russian, “do not move the throttle too—”

“I read the notes,” Andrei snapped, more sharply than he intended. He softened his tone. “Relax, comrade. If the Germans could fly it, so can I.”

He taxiied out past fields where Soviet soldiers were loading wooden crates onto flatbeds: engines, parts, machine tools. Everything that wasn’t nailed down—and some things that were—were being shipped east. German jet engines bolted to Russian test stands. German jigs and fixtures reassembled in dark Soviet factories. German engineers, some smiling and compliant, some grim and tight-lipped, waiting to find out whether their skills bought them comfort or exile.

By December of that year, men in Moscow sat around long tables, arguing over the future.

Some wanted to simply restart the production lines, paint red stars over black crosses, and build hundreds of Me 262s. Others, older, more cautious, warned that chasing yesterday’s designs was a dead end.

“We will not be the world’s mechanic, repairing German mistakes,” one engineer said. “We take what they know and leap ahead.”

In the end, they split the difference. They would not build German jets outright, but they would use German engines, German metallurgy, German aerodynamics as stepping stones. The MiG and Sukhoi bureaus received crates of blueprints and parts, along with German engineers who suddenly found themselves wearing ill-fitting Soviet overalls, their knowledge of compressors and turbine blades traded for a new citizenship they’d never asked for.

For years to come, traces of German thought would whisper through the roar of Soviet jets.

But on the ground, for the thousands of German aircraft that hadn’t been chosen, another fate was taking shape.

At Flensburg airfield, the cows moved in first.

Otto Kessler leaned on his shovel and watched as a small herd grazed cautiously between the carcasses of Junkers 88 bombers. The bombers sat in neat rows, glass noses staring blankly at the gray sky, wings streaked with rain and soot. Their engines had already been stripped, leaving empty nacelles like eye sockets.

“Back to the land,” one of the British sergeants said wryly, following his gaze. “Circle of life, yeah?”

Otto said nothing. He’d worked as a Luftwaffe mechanic for four years, hands black with oil, ears full of engine noise. He’d watched men climb into these aircraft and fly off, sometimes returning with paint scorched and flak holes in their wings, sometimes not returning at all. He’d believed, once, that he was part of something grand.

Now he wore a ragged gray uniform with no insignia and took orders from the people who’d bombed his country into rubble.

“Move it!” another sergeant shouted. “We’ve got three rows done and ten to go. Use the torches on the airframes. Salvage the copper, the aluminum. The rest goes in the pit.”

The pit was just beyond the end of the runway, a ragged gash in the earth where bulldozers shoved twisted metal, broken wings, and crushed fuselages. At night, when the wind blew right, Otto could still hear the faint clank and screech of metal shifting in its grave.

The Allies had made their decision.

The Luftwaffe was not just defeated. It would be erased.

Air disarmament teams fanned out across occupied Germany with clipboards and cutting torches. Their orders were brutally simple. Inventory every aircraft. Strip anything useful. Destroy the rest.

At one field, RAF officers supervised German prisoners as they dismantled Focke-Wulf fighters wing by wing. At another, American soldiers stood watch while Messerschmitt 262s were cut apart where they sat, their revolutionary jet engines carefully removed and crated, their airframes reduced to twisted piles of scrap.

At some sites, the volume was overwhelming. Hundreds of aircraft stood wingtip to wingtip in farm fields that had been turned into makeshift air bases. Cutting torches were too slow. Bulldozers pushed entire rows into heaps, wings snapping, fuselages folding like paper. Once the piles were high enough, fuel was poured and someone tossed in a match.

The flames were fierce, but brief. Metal doesn’t burn easily. In the aftermath, the piles sagged, charred paint flaking away to reveal dull aluminum and steel. Another bulldozer shoved the cooled remains toward waiting freight cars or into pits like the one at Flensburg.

Otto’s job was to break down the machines he had once coaxed into flight.

He stood inside the gutted cockpit of a Heinkel bomber, the dials knocked out, wires hanging like entrails. The glass canopy had been smashed, the frame already half-cut. He laid his hand on the metal where a pilot’s elbow might have rested.

“Sorry,” he muttered in German, surprised at himself.

“You talking to the plane, Kessler?” one of his fellow prisoners asked, appearing at the ladder. “They can’t hear you anymore.”

“Maybe they can,” Otto said.

The other man snorted and climbed back down, muttering about ghosts.

By late 1946, the work was mostly done. Airfields that had once hosted the most advanced air force in the world sat empty. The smell of cut metal hung in the air long after the machines were gone.

Not everywhere, though.

In Prague, the war had ended, but the factories did not empty the way Berlin or Munich’s had. When the Germans occupied Czechoslovakia in 1939, they had taken over a proud aviation industry and bent it to their purposes. Czech workers had learned to build Messerschmitt fighters and other German aircraft with the same quiet skill they’d once lavished on their own designs.

When liberation finally came, those factories still held something powerful: knowledge, tooling, parts.

And in one hangar at a field outside the city, there were Me 262 pieces stacked like puzzle parts waiting for assembly.

Petr Novak wiped his hands on a rag and looked up at the skeletal fuselage in front of him. It hung in a cradle, the curves unmistakable even without wings: the nose low and sharp, the jet intakes under the stubs where wings would soon attach.

“We’re really going through with this?” he asked, turning to the gray-haired engineer beside him.

The older man, an engineer from Avia named Hradec, nodded. “We have airframes. We have Jumo 004 engines in crates. We have drawings. The question is not whether we can. It is whether we should.”

Petr laughed. “That’s comforting.”

They were building a German jet, here, in a country that had been trampled and used. The flag overhead was different now, but the hardware was the same. It felt wrong. It also felt… necessary.

Czechoslovakia needed an air force. The war had taught them what it meant to be alone in the sky.

“So we take their machines,” Hradec said, as if reading his thoughts, “and we make them ours. We change the fittings, adjust the controls, paint them with our markings. The Americans are turning theirs into museum pieces or cutting them up. The Russians will strip them for parts and ideas. We will fly them.”

He stepped closer to the fuselage, resting a hand on the cold metal.

“We will call it Avia S-92,” he said.

On August 27th, 1946, the first S-92 roared down a Czech runway and lifted into the sky with a Czechoslovak pilot at the controls. For a brief, impossible moment, one of Hitler’s wunderwaffe belonged to a small democracy that had been written off by great powers only a decade before.

They flew them for a few short years. They trained their own pilots in jet flight, built a handful more from the stockpiles of parts the Germans had left behind. In old photographs, the S-92s look almost like the Me 262s they truly were—except for the insignia on their wings and the language spoken in their cockpits.

Then the Cold War tightened like a fist.

By 1950, Soviet pressure made itself clear. Moscow wanted its clients flying Soviet aircraft, powered by Soviet engines, maintained with Soviet tools. Czechoslovakia was told, gently but firmly, to choose between history and the future.

The Avia S-92s were grounded. Some were dismantled. A few lingered in storage, forgotten, their tires slowly collapsing under their own weight.

Petr walked through the hangar on the last day one of them sat there intact. Dust motes drifted in beams of light from the high windows. The smell of old fuel and oil clung to everything.

He put his hand on the jet’s nose, just as he’d seen Hradec do years before.

“You were never really ours,” he said softly. “But I like to think we borrowed you for a while.”

In America, the story took a different turn.

HMS Reaper was a small escort carrier, built in an American yard, loaned to the Royal Navy, and now crewed by sailors who spoke with a mix of British and American accents. In July 1945, she sat in Cherbourg harbor, her flight deck crowded with trophies.

Forty German aircraft, the crown jewels of the captured Luftwaffe.

Ten Me 262s. A handful of Arado 234 jet bombers. A Dornier 335 with engines both in the nose and tail, its push-pull configuration making it look like something out of a fever dream. Heinkel 219 night fighters. A high-altitude Focke-Wulf Ta 152, its wings impossibly long and thin.

Jack stood at the edge of the deck, the wind whipping at his hair, and tried to take it in. He’d flown one of those 262s here himself, bringing it in for a hair-raising landing on a runway barely long enough for comfort, the jet brakes protesting as the tail came down and the machine settled onto the battered French concrete.

Now it sat chained to a carrier’s deck facing the Atlantic.

“How much do you think all this is worth?” a fellow pilot, Sam Riley, asked, coming to stand beside him.

“In dollars?” Jack asked.

“In everything.”

Jack considered. “How do you put a price on a head start?”

Sam grunted. “We’re not the only ones starting, either. Heard the Brits already grabbed some of their own. And the Russians…” He gestured vaguely eastward. “They don’t exactly stand in line and fill out forms.”

Jack thought of Brauer, who’d flown with them as an instructor across Europe, then been quietly handed off to intelligence officers for debriefing. Of the engineers they’d seen in German towns, some already reassigned to new projects under new masters. Of the crates of engines and parts being loaded onto ships and trains, the invisible flow of knowledge and machinery that would shape whatever came next.

“Maybe that’s why we had to bring them,” he said. “To make sure when the next war starts, we’re not looking up at something we don’t understand again.”

Sam was quiet for a moment.

“You think there’s going to be a next one?”

Jack looked at the horizon, where the sea met the sky in a line as sharp as a sword. “Everyone’s acting like there will be,” he said finally.

Nine days later, HMS Reaper docked in Newark, New Jersey.

The German aircraft were winched off the deck, lowered by crane onto American soil. Dockworkers and soldiers stared, pointing at swept wings and strange engine arrangements. Children on the docks gaped at the black crosses and swastikas still painted on some of the fuselages.

It was like watching the war arrive one last time—but this time, under control.

From Newark, the planes were moved by rail and truck to Wright Field in Ohio and Freeman Field in Indiana. There, test pilots like Jack took them up in controlled conditions, pushing them to their limits, taking notes on every quirk, every vibration, every engine cough.

The Me 262s showed their strengths and weaknesses. Fast, yes—fast enough to outrun anything the U.S. had in 1945—but treacherous. Their engines demanded careful throttle handling. Their landing gear was fragile. The Arado 234 bomber revealed a different set of surprises, its high-altitude performance and reconnaissance capabilities opening American eyes to what a jet bomber could really do. The swept wings in German studies and prototypes, some of which had never flown, would change the way American engineers thought about high-speed flight forever.

German turbojet designs were disassembled, measured, and reimagined. Metallurgists studied their turbine blades. Aerodynamicists pored over wing shapes and control surface balances. Ideas that had been born in wind tunnels on the other side of the Atlantic began to echo through blueprints stamped with American company logos.

The jets that had once hunted Allied bombers now taught their enemies how to surpass them.

By 1950, it was the Korean War that needed attention, not a dwindling collection of German hardware.

Freeman Field’s hangars were crowded, and space was at a premium. The captured aircraft, once guarded like crown jewels, had been pushed to the back, then out onto the grass when something newer needed roof space. Winters and summers took their toll.

Paint flaked. Tires cracked and sagged. Birds nested in engine intakes.

One autumn afternoon, Jack—now a major, with lines at the corners of his eyes and jet flight hours in American machines under his belt—drove back to Freeman on a short assignment. He found himself wandering, almost without thinking, toward the far end of the field.

There, under a gray sky, the old machines waited.

The Me 262 he’d flown across France sat at a slight tilt, one main gear tire flat, the wingtip nearly brushing the wet grass. The black cross on its fuselage had faded almost to nothing. The metal around the engine nacelles bore the faint scars of years of weather instead of flak.

He walked up and put a hand on the cold aluminum, much as Brauer had once done.

“You remember me?” he murmured, ridiculous as it was.

In the distance, he heard the rise and fall of a different jet’s engine—an F-80 Shooting Star lifting off from a modern runway, its straight wings a bridge between propeller days and whatever came next. Soon, swept-wing American jets like the F-86 Sabre would be dueling over Korea with Soviet-built MiG-15s—aircraft whose design lineage could be traced, in part, to the same German research that had birthed the 262.

The circle had closed in a way that made Jack’s head hurt if he thought about it too long.

He wasn’t the only one visiting.

A young museum curator in uniform walked beside him, notebook in hand. “We can’t keep all of them,” the man said apologetically. “Some will go to the Smithsonian. One or two to the Air Force museum they’re building. But most…”

He hesitated.

“Most will be scrapped,” Jack finished for him.

The curator nodded. “Storage buildings are needed for newer test aircraft. We’ve taken what we need from these. Data. Flight reports. Design ideas. The physical hardware—” He shrugged helplessly. “We can’t keep everything forever.”

Jack understood the logic. He’d given the same explanation himself a dozen times when someone asked why a beloved aircraft was being retired or cannibalized.

It didn’t make it easier, looking at the 262, remembering the way the ground had fallen away under its wheels that first, terrifying, exhilarating flight.

Some of the planes did find new homes.

One Me 262, eventually nicknamed “Screamin’ Meemie” for the howl of its engines, would hang in the National Museum of the United States Air Force, suspended as if frozen in a dive, still wearing German markings. The Smithsonian would take the only surviving Arado 234 jet bomber, tucking it carefully into storage until a museum expansion decades later would finally let the public stand beneath its slender wings and try to imagine what it had looked like streaking high above wartime Europe.

A Dornier 335 from HMS Reaper would eventually end up in the Udvar-Hazy Center near Washington, D.C., where visitors would stop dead in their tracks, trying to make sense of its twin-engine-in-line arrangement. Children would point. Fathers would try to explain push-pull propulsion with words they barely understood.

And some would not be so lucky.

Stories persisted—never fully confirmed, but hard to dismiss—that massive Junkers 290 transports and Heinkel 177 bombers, which had mysteriously vanished from inventories, had in fact been crushed flat and buried under taxiways and terminals at what would become O’Hare International Airport.

It was a fitting metaphor, Jack thought years later, when he first flew commercially through Chicago. The jets that had once carried war now lay under the feet of travelers dragging suitcases and complaining about delays. The world had turned, and the machines of one era had become the foundations of another, quite literally.

What mattered, he realized, was that their lessons hadn’t been buried with them.

Most of the men who had touched the Luftwaffe’s last aircraft didn’t think of themselves as living in a story.

Otto Kessler finished his sentence as a prisoner and went back to civilian life, working in a small machine shop, trying not to talk about the years when his hands had known the intricacies of aircraft engines like friends’ faces. Sometimes, at night, he dreamed of torches cutting through wings, of piles of broken airframes shifting under bulldozer blades.

Petr Novak stayed in aviation as long as he could, watching his country’s designs give way to Soviet models, the great European independence he’d once believed in slowly eroding. Decades later, he would stand in a small museum and see, to his astonishment, one of the old Avia S-92s restored and painted, a relic of a brief moment when Czechoslovakia had flown jets of its own.

Hermann Heinz Brauer spent a few years in an American camp, then was quietly released. He found work in a civilian airline, flying propeller-driven transports over a peaceful Germany that was trying to forget. On rare occasions, he read an article about jets and saw, between the lines of technical description, echoes of the machines he’d flown in the last days of the war.

And Jack Morrison, like so many of his generation, wore a uniform through two eras—propellers and jets, hot war and cold. He ended his career sitting behind a desk more often than a control stick, writing reports that included dry lines like “German swept-wing research informed design decisions on upcoming high-speed aircraft.”

But every so often, on leave, he would visit a museum.

He would stand beneath the Me 262 at the Air Force museum or under the Dornier 335’s odd, stretched fuselage at Udvar-Hazy, or in front of the Arado 234 at the Smithsonian, and he would listen.

Not to the audio guides or the chatter of school groups, but to his own memories.

To the whine of jet engines on a pitted runway in Bavaria. To Brauer’s calm voice in his headset, telling him not to move the throttle too fast. To the creak of hangar doors opening on a war that was ending and a future that was just beginning.

He knew that most people who walked past these artifacts saw only shapes and numbers and plaques. They read the captions—“World’s first operational jet fighter,” “Captured by U.S. forces in 1945,” “One of only X surviving examples”—and moved on.

That was fine.

The planes hadn’t survived for everyone.

They’d survived for the generations of engineers who would study them and build better machines from their bones. For the pilots who would fly into new wars in jets that could trace their ancestry, in part, to what the Allies had found in those abandoned hangars. And for the rare visitor who would look up and feel something that wasn’t exactly nostalgia, or fear, or awe, but a blend of all three.

The Luftwaffe had been shattered by 1945. Seventy-six thousand eight hundred seventy-five German aircraft were gone by war’s end—tens of thousands lost in combat, the rest to accidents, training mishaps, or deliberate destruction. But thousands more had been left intact in that strange, suspended moment between surrender and peace.

Those aircraft did not all meet the same end.

Some were taken apart with scientific care, their designs feeding the jet age that would dominate the second half of the twentieth century. Some were flown under new flags, red stars and roundels painted over crosses, their German roots hidden beneath layers of paint and politics. Some were scrapped by the very hands that had cherished them, their loss a symbolic cleansing as much as a practical necessity. Some were buried and forgotten, their stories surviving only in rumors and engineers’ notebooks.

And a precious few were spared, cleaned, restored, and hung in quiet halls where the air smelled of dust and history.

Jack knew the answer now, when people asked the question he’d once asked himself on that French dock: What happened to the Luftwaffe planes after World War II?

They became mirrors.

They reflected the priorities and fears of the nations that captured them—America’s race to stay ahead, the Soviet Union’s hunger for parity and power, Czechoslovakia’s brief flare of independence, Britain and France’s desire to rebuild their industries, Germany’s determination to prove it could exist without them.

They became stepping stones.

Their engines and wings pointed the way toward supersonic flight, solid-state radar, guided missiles. Their failures taught engineers what not to do. Their successes whispered that the future would belong to those who embraced the strange shapes and screaming engines these aircraft had pioneered.

They became ghosts.

Not the haunting kind that rattled chains, but the quieter kind that lingered in the way a wing was swept, the angle of a tailplane, the arrangement of controls in a cockpit. A pilot in Korea, or Vietnam, or the Persian Gulf might never have heard of a Me 262 or an Arado 234, but some small part of his aircraft’s DNA carried genes that had been born in the desperate laboratories of a defeated Reich.

And, finally, they became teachers.

In museums, under the fluorescent glow and the murmured explanations of guides, they taught a different lesson—not about tactics or thrust, but about what humans do with their brightest ideas when they are afraid.

Jack’s granddaughter once asked him, on a family trip to the museum, why he was staring so long at a gray jet with strange, clumsy-looking engines.

“Because,” he said slowly, “this is where one world ended and another began. And I got to see the moment in between.”

She squinted up at the plane, then back at him. “Is it a good story?” she asked.

He thought of hangar doors opening on silent ranks of abandoned aircraft. Of secret midnight ferry flights across war-torn Europe. Of Soviet trains rattling east with stolen engines. Of Czech mechanics piecing together jets from crates. Of German prisoners cutting apart their own handiwork under Allied guard. Of museum halls and airport runways built on bones of aluminum.

“It’s not a simple one,” he said. “But yes. It’s a story worth telling.”

His granddaughter nodded, then tugged at his hand. “Come on,” she said. “They’ve got a space shuttle in the next hangar.”

He allowed himself to be pulled along, past the Me 262, past the Arado 234 and the Dornier 335 and the other relics of that strange, feverish era at the end of propellers and the start of jets.

Above them, untouched by the chatter and footfalls below, the Luftwaffe planes hung motionless, caught forever in an artificial flight.

Once, they had been instruments of terror and destruction.

Now, at last, they rested as artifacts: pieces of a long-finished puzzle, witnesses to the moment when the world heard the whine of a jet engine for the first time and realized, with a chill, that the future had already arrived.

News

CH2. What Japanese Admirals Realized 30 Days After Pearl Harbor

What Japanese Admirals Realized 30 Days After Pearl Harbor The rain in Tokyo that morning was a thin, steady veil,…

CH2. Why No One Has Ever Shot Down an F-15

Why No One Has Ever Shot Down an F-15 The first time Captain Jake Morgan really felt the weight of…

CH2. What Japanese Pilots Whispered When P 38s Started Killing Them In Seconds

What Japanese Pilots Whispered When P 38s Started Killing Them In Seconds Lieutenant Commander Saburō Sakai had killed sixty-four men…

CH2. WWII’s Craziest Engineering: How the Navy Raised the Ghost Fleet?

WWII’s Craziest Engineering: How the Navy Raised the Ghost Fleet? Your vision is zero. The darkness is so thick you…

CH2. German Ace Returned to Base and Discovered 5,000 Luftwaffe Planes Destroyed in Just 7 Days

German Ace Returned to Base and Discovered 5,000 Luftwaffe Planes Destroyed in Just 7 Days January 15, 1945, began like…

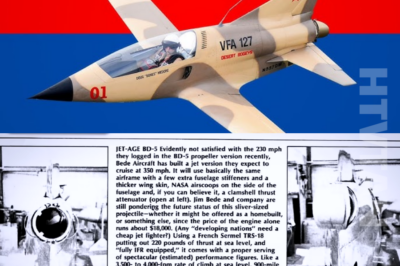

CH2. This ‘$2,000 Jet’ Seduced Thousands of Pilots… Then Turned On Them

This ‘$2,000 Jet’ Seduced Thousands of Pilots… Then Turned On Them The first time the jet tried to kill him,…

End of content

No more pages to load