Was On Bed Rest After Surgery When My Sister Texted, “You Can Watch My Kids For A Week, Right? I Just Booked A Trip To Paris!” I Could Barely Walk, But She Didn’t Care. So I Decided To Teach Her A Lesson She’d Remember Forever. When She Came Home From France, She Walked Into A…

Part I — The Text and the Stitches

The morphine button glowed like a sleepy firefly on the rail of my hospital bed. I pressed it just to dull the ache that bloomed each time I shifted. Abdominal surgery is a blunt teacher; you learn quickly how many muscles are involved in the ordinary act of breathing.

That’s when my sister’s text vibrated my phone off the blanket.

You can watch my kids for a week, right? I just booked a trip to Paris!

No greeting. No “how are you feeling?”. No acknowledgement of the IV still taped to my wrist, the bruises blossoming where the nurse had struggled to find a vein.

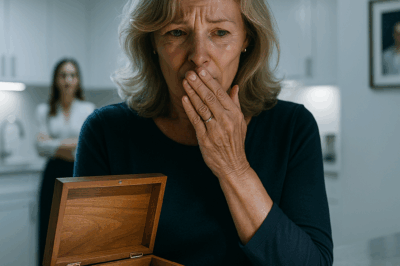

I stared at the words until the screen dimmed. Then I brought them back and read again, hoping they would choose different letters this time.

My sister, Tessa, has always been a weather system unto herself—loud, dramatic, gorgeous in a way that made people mistake magnetism for character. I used to call her a hurricane of charm. These days I called her a hurricane and left it there.

She hadn’t visited the hospital. Not once. She had sent a bouquet—lilies, which made my sinuses swell—and a voice note in the tone of a TikTok confessional: Babeee, so proud of you, you’re so strong, can’t wait to have you back! I’m slammed this week, so I’ll check in later. Mwah.

Later, it turned out, was Paris.

I typed two words back: I can’t.

Her read receipt popped up immediately, and two dots pulsed in the mean little way they do when someone is crafting a reply they think is more important than anything you could possibly say.

C’mon. It’s not a big deal. They’re easy. You’re home all day anyway. Mom said you’ll be fine by then.

Booked nonrefundable.

She’d always arranged her life like that—snapping a leash around everyone else’s choices by calling things done before anyone agreed. I used to think it was confidence. I’d finally learned it was cowardice with a travel rewards account.

I didn’t answer. The morphine warmed through my bloodstream, and the world smudged at the edges. I slept.

Two mornings later, the discharge nurse read my instructions while scanning my face for comprehension.

“No lifting more than ten pounds for two weeks,” she said. “No stairs for three days. Hydration is critical. If you spike a fever…?”

“I call,” I said. “I know.”

“Do you have support at home?”

I opened my mouth to say yes, because telling strangers no made something ancient in me panic, and then my phone buzzed again. A picture of the Eiffel Tower sat in the text preview like proof of a lie told out loud.

“I’ll manage,” I said instead.

The rideshare driver helped me to my door and passed me my overnight bag as if it weighed nothing. Closing the apartment behind me was like sealing a vault. I slid down the wall until I was sitting on the entry rug, forehead on my knees, breathing through the first screaming tug of stitches.

And then, right on cue, a knock rattled the frame.

I didn’t recognize the knock. Tessa’s knocks had always been performative—tap tap KNOCK, like she was announcing herself in three acts. This knock was hurried and practical. When I opened the door an inch, a burst of cold air and the smell of caramel popcorn seeped in around the edges.

Tessa shoved past me like a stagehand pushing scenery. The kids, Milo (5) and Daisy (7), trailed and stared with large, solemn eyes above their winter scarves. Two duffels, a Pack ’n Play I’d never agreed to, and a grocery bag of easy mac hit the floor with thuds my stitches counted one by one.

“Okay!” Tessa said, breathless and beautiful, sunglasses perched on hair sprayed into glossy agreement. “The packing list is in the blue bag. They both hate naps but they’re super easy. I’m late for the airport. Kiss-kiss!”

“You can’t leave them here,” I said. I meant to say it louder.

She looked at me like I’d dropped a plate at a restaurant that belonged to her. “Lena, please. It’s one week.”

“I just had surgery.”

“I know.” She squeezed my shoulder in the way someone might pat a co-worker they’re about to fire. “You’re so good at this stuff.”

And then she was gone. The door clicked. Her heels clattered away. A Lyft door slammed. Silence.

Milo’s mitten fell off, and he began to cry in the small, bewildered way kids cry when their bodies can’t find their mothers in a room that smells wrong.

I crouched. The room tilted.

“Hey,” I said. “It’s okay.” I said it in the voice I’d borrowed from our mother before our mother taught me to be quiet and then forgot to stay herself. “We’re going to figure this out.”

While they watched a cartoon on my laptop, I texted two people: Nia, my neighbor down the hall, who fed me soup when I had the flu last winter, and Mara, who ran intake at the legal aid office where I did design work pro bono.

Me: Are you home? I need a hand with the kids.

Nia: Be there in 10. Do you need Advil or a shot of tequila?

Me: Yes.

Me to Mara: Hypothetically, if someone abandoned their kids with a post-op sister to go to Paris, what would you call that?

Mara: Hypothetically? Child neglect. If you want help, I’m in the office by 3.

I looked at Milo and Daisy: an open bag of popcorn, socks already mismatched, eyes huge.

“Do you want grilled cheese?” I asked.

They nodded in the solemn unison of tiny people who don’t yet know how to lie.

By 2 p.m. I had exactly one thing I didn’t have when Tessa texted: a plan. Not a revenge plan. A survival plan with receipts.

I took pictures of my surgical discharge paperwork and of the kids’ bags as they were—scarves damp, nothing labeled, medications absent. I recorded a quick voice memo describing the day: Dropped at 9:40 without notice. No written instructions. No emergency contacts. Texted her at 9:43 and 9:58. No response.

Nia slid into my kitchen with her hair in a scarf and a tray of brownies like she was born to be a cavalry.

“Have you eaten?” she asked.

“I can’t tell,” I said.

“That’s a no.” She unpacked Tupperwares and instructions with the efficiency of someone who has survived being a person in a body. “I’ll do school pick-ups if needed. You do not lift that child. And you call legal.”

“I already did,” I said. “At three.”

“That’s my girl,” she said, and patted my cheek like a benediction.

By the time the cartoon episode ended, the list in my head had become a document on my desktop named If she laughs, call this instead.

Part II — The Visit and the File

The legal aid office smelled like drying paint and old coffee. A toddler’s crayon drawing of a courthouse hung crooked in the lobby. When Mara emerged, she scanned my face the way emergency nurses do—full body triage in one second.

“How bad?”

“Paris,” I said.

She nodded once. “We’ll start with a safety plan.”

We sat in a small, bright room with Ikea chairs and a box of tissues that had seen some things. Mara dictated while I spoke, a practice she said helped when everything went sideways later and you needed to recall who said what when your hands were shaking too hard to write.

“Children’s names, ages…drop-off time… condition at drop-off… your post-op restrictions… sister’s departure confirmation…”

Mara looked at my phone. “She posted stories?”

“Three,” I said. “One with champagne, one with a croissant, one in front of the Louvre.”

“Screenshots,” Mara said. “Time stamps. Archive them.”

She walked me through the steps like we were assembling furniture: report through the CPS hotline, go on record with my surgeon’s office, notify the pediatrician about the kids’ sudden change in caregiver, request a wellness visit to create documentation of the home.

“Do you want to keep them with you?” she asked, not casually and not pressuring either.

“Yes,” I said, before I had time to rehearse the answer in my head and find a more palatable one.

“Okay,” she replied. “Then we file for temporary guardianship until your sister returns. Given your medical status, we tie in community support—neighbors, me, anyone who will attest. If you need respite, you text me. If she tries to retrieve them without plan, you call me and 911.”

“What if she… comes back smiling and apologizing?”

Mara’s mouth twitched. “Then you let the paper speak first. People who abandon tend to be excellent with speeches.”

CPS showed up the next morning—Ms. Alvarez, hair pulled into a bun, a tote filled with forms, and a magic trick that produced bubbles out of thin air for Milo. She was professional in the way of a person who has heard every version of a sad story and still believes better is possible.

She checked the fridge, the medicine shelf, the smoke detectors. She photographed my discharge papers and the kids’ bags. She asked Daisy to show her where the bathroom was and clocked that it was clean. She watched me bend at the knees because my abdomen wouldn’t let me do anything else.

“You’re doing enough,” she said, and I almost laid my forehead on the table and wept at the permission in that sentence.

I signed her form authorizing a wellness check on the kids’ pediatric records. She left me with a stack of paper, a list of numbers, and a card with her cell on it.

“Text me if she reaches out,” she said. “Text me if you have to go back to the hospital. We will not let you do this alone.”

When Tessa called on day four, her voice had a champagne bubble at the top.

“You’re fine, right? I thought you’d take this so personally. Don’t be so dramatic—it’s one week.”

“Okay,” I said, and recorded the call. “In one week, explain to Ms. Alvarez why you left a post-op caregiver with two kids without provisions.”

Silence kissed the line. “Who’s Ms. Alvarez?”

“CPS,” I said.

“Jesus, Lena. That’s excessive.”

“Stitches are excessive,” I replied. “Neglect is illegal.”

She hung up.

I filed for emergency guardianship that afternoon. The form asked me to describe my relationship to the children. I wrote Aunt. Caregiver. The person who answered when their parent did not. It felt maudlin and self-aggrandizing. It also felt true.

When Nia brought soup that night, she found me on the rug with the kids making a fort out of blankets and the kitchen table. Milo’s hair stuck up in the way toddlers’ hair does when gravity is a suggestion. Daisy asked me if Paris had a jungle gym. I said I didn’t know.

“Do you think Mom is bringing us a toy?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said, and the word reached into my ribs and squeezed like a fist. “I think she’ll bring something.”

“What will she bring you?” Nia asked later when we washed bowls together.

“A story,” I said. “She’s always had a bag full of those.”

Part III — The Landing

She arrived on a Sunday, sunbrowned, hair spun-gold by a salon more expensive than rent. Her suitcase clacked up the walk. I had left the security chain on out of pettiness or self-preservation—I’m still not sure which. When she jiggled the handle, the chain stretched and held. It sang a small metal warning.

“Lena!” she called. “Surprise!”

I opened the door enough to see the sunglasses perched on her head. “The surprise was the note,” I said.

“Oh, God, you’re still on that?” She laughed like I had failed to catch a punchline. “Where are my babies?”

“With people who fed them while you were photographing pastries.”

She pushed the door and the chain clattered. “You’re unbelievable. Where are they?”

“With Child Protective Services,” I said. “They’re safe. They’ll be back when you can guarantee it.”

Her face did the thing it does when her world forgets to accommodate her—first confusion, then anger, then the performance of a cry, then fury that the cry didn’t sway. She tried all four in a loop before settling on outrage.

“You reported me?”

“I reported what happened,” I said. “The note reported you.”

“There was nothing wrong with what I did! You said you could handle it.”

“I didn’t say anything. You told me your plan and then left. Plans require consent. What you did has a word. It’s just not a word you’ve been willing to learn.”

She gulped air. The suitcases tipped as if they’d decided on their own not to participate. “You’ve ruined my life.”

“You’ve delayed your trip back to denial,” I said. “If you want the kids, you show up to the case plan tomorrow at nine. You bring proof of childcare for when you’re at work. You bring the pediatrician’s number. You bring a written apology to Daisy and Milo, not to me. You bring your ID and leave the selfies.”

“How dare you talk to me like—”

“Like an adult?” I asked. “Like the other adult in this family? Easily.”

She spun on a heel and clacked away. The luggage slammed, the Lyft pulled off, and the apartment stared at me with the blankness of a scene-change. I put the chain back on and slid down the door until my stitches warned me to stop.

On Monday, she arrived to the family services building in a blazer and a watch that I suspected had been purchased with a credit line that would outlast this sincerity. Ms. Alvarez greeted her with the same steady, un-fussed voice she used with me.

“We ask for accountability,” she said. “We expect change. We provide a path. We do not accept excuses.”

Tessa nodded in the shape of humility. There is a way to nod that is not an agreement; it is a promise that you’re storing the right words to use on a different audience later. I braced for it.

The case plan read like a recipe for a life Tessa had never used an oven for: parenting classes, weekly visits, a steady job, drug test clean, no leaving the children without a named caregiver, no travel without notice, no disappearing.

“Can I still go to New York for Fashion Week?” she asked.

Ms. Alvarez did not sigh. “Not without arranging for care that is approved. Not without notice. Not while you are on an active neglect case.”

“It’s work,” Tessa said, as if that incantation had ever produced a fairy godmother.

“Mothering is work,” Ms. Alvarez said. “It’s the job you applied for when you brought them into the world. It’s the job you left when you brought your suitcase to my door.”

Tessa swallowed. The swallow forced her to bow her head in what looked like prayer.

I did not speak in that meeting. This was not my stage. I was backup choir with a file folder.

Part IV — The Lesson, the Long Way

If this were a revenge story, the moral would be clean. She’d suffer. I’d triumph. The end. But life kept refusing to stay in the shape of the story I wanted.

Daisy asked for her mother every night and scheduled her sadness like a professional—6:35 p.m. after a bath, tearful and splotched-cheeked, whispering into her bear, “She said she’d bring me a keychain with my name on it.” Milo sang his version: “Mama mama mama,” until the syllables fell off his face and onto my shirt.

The supervised visits started awkward. Tessa stared at her children like they were asymmetrical mirrors that showed her a version of herself she didn’t like. She corrected Daisy’s grip on crayons. She took photos of Milo and then forgot to wipe his nose. She apologized to me, never to them.

Then, slowly, she stopped narrating her goodness and started practicing it. She learned to cut grapes in half. She learned the sound of Daisy’s fatigue before it became a tantrum. She learned that the way Milo stares at a dust mote in sunlight is called attention, not disobedience. She said “I’m sorry” once, when Daisy reminded her that the Paris keychain had not arrived. I saw the effort it cost her. I gave that small muscle room to grow.

In court, the judge never called me a hero. Good. Heroes don’t change diapers at 3 a.m. Heroes don’t fill out WIC forms or spend forty minutes coaxing a toddler into a car seat. Caregivers do. I learned to love the demotion from narrative center to daily chorus.

Six months later, we returned to the same fluorescent courtroom for a review. The file had thickened. So had my calves from carrying a squirming toddler up three flights of stairs. Tessa had thickened, too—less gloss, more bone. She brought an employment letter and a calendar with the dates of her parenting class marked with checkmarks I recognized as the handwriting of someone who had finally discovered the arresting rhythm of responsibility.

The judge adjusted the custody: joint legal, primary physical with me for the next six months, then increased time for her contingent on consistency. Systems love that word. So do I. Consistency is not glamorous. It’s the thing that makes love survive past the cheap and mean days.

When the gavel fell, Tessa and I walked out into the heat. She stood with her hand on the peeling paint of the building like she needed something chipped and real under her palm.

“Do you hate me?” she asked.

“No,” I said. “I hate what you did. And I love what you’re trying to do now. Those can be true at the same time.”

“Will you ever trust me again?” Her voice was small and honest, a combination I hadn’t heard from her since we fought over a cardigan in ninth grade.

“I’ll trust you when you’ve earned it,” I said. “And I’ll help you earn it because it’s not fair to expect a person to learn a skill nobody taught them.”

She looked at me as if I’d offered her a bribe. Then, unbelievably, she laughed—not the trick laugh she used when she got her way, but the laugh our mother had when she heard a stupid joke at a picnic and couldn’t stop. Something in me loosened the way stitches do when the bruise has faded and it’s time to let new skin take the stress.

We didn’t hug. We put the kids in their car seats. She checked the buckles. I checked her checking. We both exhaled.

Part V — What She Walked Into

Three seasons later, after summer with sunscreen battles, fall with leaves shoved into bags and then dumped again for the joy of it, and winter with endless mittens, she left for a weekend work trip she had arranged properly—childcare lined up, caseworker informed, emergency numbers printed and stuck to the fridge.

And when she came home, she walked into a different house.

Not mine. Not hers. Ours, in a way I had honestly believed could not exist. The kitchen counters were the same, but the magnets were different—school calendars she had actually attended. Daisy’s scribbled “MOM IS COMING FRIDAY!” with seven exclamation points. Milo’s terrible stick figure with a circle head that was clearly a clown but he told us was “Mama’s smile.”

“How was the trip?” I asked.

“Long,” she said. She leaned in the doorway like people do who didn’t know their bones held their bodies up until they start being asked to be reliable.

“You look tired,” I said.

“I am,” she replied, and for the first time I didn’t hear a reason to fix it in her voice. “But the kids are fed and…” She looked around. “…and there’s nothing burning.”

“Low bar,” I said.

“The right bar,” she countered, and smiled.

On the table, there was a note. Not a taped, careless note like the one that started this. A folded one with a list Tessa had written across the top: Lunchboxes packed, laundry folded, permission slip signed, Eli’s pediatrician appointment confirmed, Daisy’s library book in her backpack. She had written the list to herself. She had left it for me. It was not an oath of change. It was a record of it.

I slid a white envelope toward her. “From CPS,” I said.

She flinched. “Am I—?”

“It’s a letter of case closure,” I said. “They closed it on Tuesday.”

She exhaled like she’d been holding a lungful of ocean for a year. She leaned her forehead on the envelope like it was cool tile. Then she straightened.

“I got you something,” she said. She took a small box from her bag. Inside was a keychain, cheap metal, Eiffel Tower. To Lena, for the weekend we didn’t take, the tag read. “It’s silly,” she said. “I got it at the airport gift shop. It felt like a confession I could carry that wouldn’t weigh anything.”

I put it on my house keys. “We’ll go someday,” I said.

“Together?” she asked, and there was no entitlement in it; there was hope like a candle in a storm.

“Together,” I said. “But not until Daisy is old enough to complain about museums.”

We set the table. The kids yelled because they were alive. The apartment was ordinary and loud, like the inside of a heart that has decided to beat on purpose.

If you came here for the explosion, I’m sorry. The bang was small and happened at the beginning, with a note and a door and a call. The rest was paperwork and soup and holding a line long enough for someone else to learn how to stand.

When my sister came home from France, she walked into a life she almost lost. Not because I destroyed her—but because I refused to help her destroy herself. That was the lesson. It took both of us to learn it.

The scar from my surgery is a thin pale line now, a secret only I see in the mirror each morning. It twinges in the rain. It reminds me that healing is not the absence of ache. It is the choice to move anyway.

Tessa texts before she comes over now. Sometimes she asks if she can drop the kids early because she’s tired. Sometimes I say yes. Sometimes I say no. We both survive it.

And on the fridge, next to the closed-case letter and a terrible drawing of the Eiffel Tower with five legs, there’s something new: a Polaroid of all four of us at the park. Daisy’s hair is everywhere. Milo has yogurt on his shirt. Tessa’s eyes are soft. I look like someone who can lift ten pounds again—of groceries, of responsibility, of grace.

We’re not Paris. We’re better: we’re a family with a calendar and a second chance. And that’s a lesson you can’t learn on a red-eye.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. My Dad Removed Me From the $30K Dubai Trip I Funded—To Give My Spot to My Brother’s Fiancée

My Dad Removed Me From the $30K Dubai Trip I Funded—To Give My Spot to My Brother’s Fiancée Part I…

CH2. My Parents Kicked Me Out in a Blizzard. They Said I’d Come Crawling Back, But Then…

My Parents Kicked Me Out in a Blizzard. They Said I’d Come Crawling Back, But Then… Part I — The…

CH2. My parents treated me like a maid, until at my grandfather’s funeral…

My parents treated me like a maid, until at my grandfather’s funeral… Part I — The Smallest Room My mother…

CH2. At Dinner, She Smirked: “My Ex Just Texted – I’m Meeting Him For ‘Closure’ Tomorrow.” I Just Nodded: “That’s Thoughtful.” The Next Morning, Her Bags Were Professionally Packed, The Locks Changed, And A Moving Truck Waiting. When She Came Back From Her “Closure” Meeting… She Realized I’d Already Closed Everything…..

At Dinner, She Smirked: “My Ex Just Texted — I’m Meeting Him for ‘Closure’ Tomorrow.” I Just Nodded: “That’s Thoughtful.”…

CH2. Parents Told Me, “Skip Thanksgiving — We Need Space.” But Their Regret Came Quickly

Parents Told Me, “Skip Thanksgiving — We Need Space.” But Their Regret Came Quickly Part I — The Message The…

CH2. My Daughter Betrayed Me… But My Late Husband Saved Me

My Daughter Betrayed Me… But My Late Husband Saved Me My daughter thought she could take everything—my beach house, my…

End of content

No more pages to load