They Pretended to Be My Parents—But Grandma’s Final Words Unmasked the Truth.

Part I — The One Who Stayed

Betrayal doesn’t always arrive with fire and thunder. Sometimes it walks in softly, wearing polite smiles, whispering comfort, pretending to care, while already measuring what it can take next. That’s how mine began.

I stood in black beside my grandmother’s coffin and tried to memorize the last shape grief would take in this house. The old church on Hawthorne smelled of beeswax and lilies; the worn hymnals whispered along the pews. People said kind things they would forget by Tuesday. My mother—Susan—pressed napkins into polite hands and accepted condolences like a hostess managing seating for a fundraiser. My father—Steven—kept stepping into corners to take calls, his voice dropping into that cashmere tone he used when he liked the numbers.

We went home to the three-story Victorian at 312 Hawthorne, the house that had raised three generations and one girl who needed raising more than most. The rooms looked staged, as if grief had been vacuumed out of the corners. Susan rearranged coasters. Steven stood in the window counting the ways a yard sells faster. No one said Grandma’s name. No one hummed the nonsense song she’d always hummed while stirring sugar into tea.

“Anna,” Susan said finally, setting her coffee down with a click so sharp it felt like a verdict. “Your grandmother would want us to handle her affairs quickly. We’ll meet her lawyer tomorrow.”

“Her affairs?” I repeated. “Not her legacy?”

“Bring any keys you still have,” she added, the way people add something they want more than your company. “We’ll need to start sorting the property.”

Property. Not home. Not history. Not the porch where Grandma and I shelled peas in July. I nodded because it was easier to move the world an inch at a time than to flip it over in one day.

I found the note that night: a single sheet, folded once and left on my pillow like an invitation. Anna, written in Grandma’s looping blue. My hands trembled.

My Anna, if you’re reading this, I’m gone. You were the one who stayed. The one who listened. The one who saw me not as a burden, but as someone worth knowing. Tomorrow, stay quiet. Let them talk. Let them show you who they really are. Then go home. The keys you give them won’t open what matters.

All my love, Grandma.

I read it three times. Then a fourth. The house creaked the way old houses creak when they are trying not to gossip.

The next morning, the office of Ames & Duvall smelled like lemon oil and old cases that still called in the night. Carol Ames herself met us—steel-haired, clear-eyed, the kind of woman who could direct a hurricane without raising her voice. She invited us to sit. Steven sat first, the way men sit when they believe chairs are built for them. Susan crossed her legs and arranged her face into something pious.

“Your mother prepared everything thoroughly,” Ames said to them, and opened a folder thick as a Bible. “Mrs. Sullivan was very specific.”

She read bequests the way a good priest reads a psalm—careful, reverent, seeing what she says. A necklace to the church friend who drove Grandma to appointments. The antique clock to Mr. Grier next door, who fixed its stubborn pendulum with more patience than talent. Donations to the library and the food pantry in amounts that would make those places weep in the back room. Susan’s smile tightened. Steven’s pen clicked a rhythm against his knee.

“And the residence at 312 Hawthorne Street,” Ames continued, “including all contents, land, and associated financial accounts, is to be left to the one who stayed.”

Steven laughed, short. “That isn’t a legal term.”

Ames slid a smaller envelope from the folder and broke the seal. “Your mother clarified,” she said, and read:

The one who stayed is the person who cared for me without obligation, who stayed through sleepless nights, who read to me when my eyes were weak, who never left when others found excuses.

Ames looked up and right at me. “She meant you, Anna.”

Silence sat down in the chair beside me and held my hand. Susan’s jaw clicked. “That’s absurd. Mother had lapses.”

“Mrs. Sullivan’s memory was intact,” Ames replied, unbothered. “We met weekly for six months and reviewed every clause.”

She lifted another page. “There is one more addendum.”

Susan and Steven leaned forward together, marital choreography practiced over decades: brace, counter, pounce.

For legal accuracy and truth: Anna Marie is not the biological daughter of Susan and Steven Bennett. She is the daughter of my late sister, Pamela Warren, who passed shortly after Anna’s birth. I became her guardian when Pamela died, though adoption papers were never finalized by the Bennetts. Anna has been my responsibility and my greatest joy since she was three days old.

The words landed. The room changed. Susan went pale; Steven went mean. “This is nonsense,” he hissed. “Anna is our daughter. We raised her.”

Ames slid a separate folder across the desk. “Guardianship records,” she said. “Signed by Judge Hopkins, twenty-six years ago. Rebecca Sullivan’s signature. Pamela Warren’s signature. And the infant footprint of Anna Marie.”

My name inked into a truth no one could rearrange.

Ames’s voice softened. “Mrs. Sullivan wanted Anna protected from any challenges. She knew grief makes people greedy.”

Susan stood so quickly her chair barked against the rug. “We have rights,” she said. It almost sounded like a question.

“No,” Ames said, not unkindly. “You don’t. You never adopted her. She’s of age. The estate transfers fully to her, as specified.”

Steven shoved his chair back until it hit the wall. “We’ll contest.”

“You may,” Ames allowed. “If you do, you forfeit the $50,000 Mrs. Sullivan left you in a separate trust. She insisted on that condition.”

They froze. Greed has a way of taking the wheel from rage. Then, without a glance at me, they left. The door closed with a softness more insulting than any slam.

“Are you all right?” Ames asked.

The truth is rarely a single feeling. It comes layered—shock first, then grief, then a bright sharpness that feels like oxygen. I nodded, then shook my head, then nodded again.

“She knew,” I said. “She knew they’d do this.”

“She did,” Ames said. “And she left something for you at home.”

I drove to Hawthorne Street with the radio off, as if silence could keep time from rushing me. The porch light burned like a beacon. Grandma had kept it on every night of my life. Home should always be easy to find, she’d said.

Upstairs, the sewing room still smelled of cotton and cinnamon. The old Singer stood patient in the window light, a seam paused mid-stitch the week her fingers started to fail. I knelt at the bottom drawer—the one she always locked—and slid the small brass key in. It turned with a feel that made memory ache.

Inside: a narrow photo album with a leather spine rubbed smooth by decades, and a letter.

Anna,

This truth will hurt. I wish I could be there to hold you while you process it. My sister Pamela was brilliant and brave and broken in places nobody could mend. She asked me to take you; I never regretted a moment. Susan and Steven wanted children. They promised to adopt you. They never did. I think they always saw you as mine, not theirs—and they were right.

I kept every piece of your story, even the parts they wanted buried. You don’t owe anyone silence anymore.

Love always, Grandma.

The album held proof in images: my grandmother on the hospital steps, hair escaping pins, face luminous with exhaustion and joy; Pamela beside her, my eyes in her face and my mouth in her smile; a series of tiny milestones: my fist around Grandma’s finger, my first steps between sewing table and window, crayon drawings of a world that seemed to accept me.

The phone started at six in the morning and did not stop. Anna, sweetie, let’s talk in voices practiced for therapy. After everything we’ve done for you in voices trained for guilt. That manipulative old woman in voices that had always loved the sound of themselves.

I didn’t answer. I met Ames again. She showed me the map my grandmother had drawn in law: the house held in trust, the accounts fed and guarded, clauses like steel woven with love like light. “We expect them to file anyway,” she said. “If they do, we play the tape.”

“The tape?”

She smiled. “Your grandmother recorded a video with me explaining every decision. Competency validated. Intent detailed. Generosity documented. Judges don’t argue with cameras.”

They filed. The judge watched Rebecca Sullivan outline a lifetime of choices with the calm competence of a woman who had managed grief, garden, and gas bill without applause. The challenge died in five minutes. Outside the courthouse, Susan’s lips trembled; Steven’s hands shook—rage or withdrawal, I could not tell. They tried to catch my eye. I looked at the courthouse plaque and traced the lettering with my gaze.

Three weeks later, Ames sent a note: First National Bank—Safe Deposit 217. Final instructions.

The box held a flash drive, a checkbook, and one more letter in blue ink.

Every year for twenty years, Susan and Steven borrowed money from me. I never asked for repayment. It totals $180,000. Let it go. That debt is with me now. The checkbook is yours. Use it for something that grows, not something that burns. If they come knocking, remember: peace can be the loudest revenge.

I closed my eyes and saw the kitchen clock my grandmother wound every Sunday, her fingers gentle and sure. I knew what to do.

I called my friend Marco—artist, contractor, the kind of person who can turn sadness into something people want to stand inside. We sat at the kitchen table with graph paper. We planned a community library for the front parlor, cooking classes for the big kitchen, a garden behind the carriage house where kids could get dirty on purpose. We called it The One Who Stayed.

When the first neighbors wandered in—curious, cautious—Mrs. Patel from across the way touched the new shelf as if it might bruise. “Rebecca would approve,” she murmured, and I felt my grandmother’s laugh in the plaster.

Four months later, Susan and Steven stood on the porch. Their silhouette in the stained glass looked like a story missing its last page.

“We lost everything,” Steven said. His voice had new gravel. “The business. The house. We need… anything.”

Susan’s eyes were dry and hot. “She turned you against us,” she snapped. “She poisoned you.”

“I’m her student,” I said. Not her puppet.

I handed them an envelope. Inside: a single check with no dollar amount and the memo line filled with two words in blue ink: Paid in full.

“She covered your debts,” I said. “You don’t owe me, and I don’t owe you.” I closed the door gently. Through the beveled glass, I watched them argue their way down the walk.

I made tea. I poured a cup for the space at the table where my grandmother had always sat. The house sighed contentment, floorboards creaking under my bare feet like a friendly dog shifting in sleep.

Some stories end with fireworks. Mine ended with a deed, a key, and a cup of tea cooling in a pool of winter sun.

Part II — What a Signature Can’t Change

Word travels along Hawthorne Street faster than the mail. People came with pies and questions. Some asked if I’d forgiven the Bennetts. Forgiveness, I discovered, is not a performance. It is remembering and choosing peace anyway.

“You’re tough,” Marco said, leveling a shelf. “Tough isn’t hard. Tough is precise.”

“Grandma taught me to hem sheets straight,” I said. “Turns out the same technique applies to boundaries.”

The One Who Stayed opened fully in spring. We stacked paperbacks by color, and the kids reorganized them by favorites, which is an equally valid taxonomy. Mrs. Patel taught the first cooking class—samosas and stories. In the garden, a little boy named Amir found a beetle and declared it our logo. We taped his drawing on the donation jar.

The Bennetts’ texts slowed to embers, then ash. Once, Steven sent a final volley—We’re your parents—and I typed You were and deleted it and typed You pretended and deleted that too and then I turned my phone over and watered the basil. Water has its own logic.

Ames stopped by with scones and paperwork. “Your grandmother would like what you’re doing,” she said, signing the last of the transfer documents. “She once told me she wished the house could be useful to the street.” She looked around at the bustle—the toddler storytime, the teenager in the corner editing a college essay, the smell of onions and cinnamon from the kitchen—and nodded to herself. “I think you’re there.”

Neighbors began bringing pieces of their lives for the mantle: a photograph of the class of ’72 drumline in front of the church steps; a newspaper clipping about the library’s first female head librarian; a recipe card for a casserole that had saved at least three marriages by rumor alone. The house learned new names and remembered old ones. On Sundays, I lit a candle beside Grandma’s picture and told her the week’s news the way we always had.

One afternoon, a woman my age hovered at the threshold with the awkwardness of someone who came to ask and stayed to eavesdrop. She kept glancing toward the sewing room as if it might let her in. “Can I help you?” I asked finally, gentle.

She flinched and then smiled. “Sorry. I… knew Pamela. In rehab,” she said. “We kept promising to get better for the babies.” Her voice made promised sound like a rope. “I heard about the funeral too late. I wanted to tell Rebecca thank you.”

“She’d like that,” I said, and my mouth surprised me by not breaking.

The woman looked at me properly then. “You’ve got Pamela’s eyes,” she said. “And Rebecca’s stubborn chin.”

We sat in the sewing room and I showed her the photo album. We cried the way women cry when grief meets proof of life. Before she left, she placed a tiny crocheted hat on the machine—a preemie cap, purple and soft. “For the next baby who needs staying.”

The house collected these breadcrumbs and learned to bake with them.

I found small ways to honor Rebecca’s meticulous justice. When a man shouted at his daughter in the library because she picked the “wrong” book, I stood and said the simplest sentence I own: “We don’t do that here.” He blinked, offended by the audacity. “She should read the classics,” he said, gesturing at a shelf. The girl shifted behind him and slid a graphic novel into her backpack, eyes gleaming. “We do this, though,” I added, gesturing to the room. “Choice.”

Mrs. Patel leaned over to the girl and whispered, “The classics can wait.” I pretended not to see the comic slip into a bag. Justice, like sugar, melts best when stirred in quiet.

On hot nights when sleep took the long way home, I walked barefoot, listening to the house. Floorboards learned my weight again, adjusting their creaks to my habits. The porch swing moaned into a friend. The kitchen window knew exactly what to do with morning light.

Sometimes I said Susan and Steven out loud just to strip the titles from the people. The names sounded smaller without the costumes. If bitterness tried to drag a chair to the table, I handed it a to-go cup. Peace can be the loudest revenge, the letter had said. I practiced.

I kept the checkbook closed for a long time. Money is a solvent; it dissolves and distorts in equal measures. When the boiler complained in January, I opened it. It held enough to repair and enough to plan and enough to leave a zero at the end of the balance after both. I called Union & Son because they installed the original. The son was now seventy-one and moved like he’d made a deal with his knees. He patted the pipes and said, “She’s got life in her yet,” and I chose to believe him because choosing to believe is sometimes the only maintenance a heart needs.

Every month, an envelope arrived from Ames with some quiet closing of one of Grandma’s tabs—a tithe to the church, a scholarship to the library’s GED program, a line item to the veterinary clinic for the feral cat who lived beneath the stairs and hated everyone equally. Rebecca believed in paying bills before they learned to charge interest.

I took a class on estate law for non-lawyers. I learned how trusts breathe and when to choose revocable over irrevocable and why endowments make small buildings outlive big men. One evening, I caught my reflection in the kitchen window—messy bun, paint on my sleeve, a smudge of flour on my cheek—and thought, I look like someone who stays.

Marco built a little stage in the garden. Kids wrote a play about a beetle who saved a village by convincing the villagers to plant what the beetles liked to eat. It was a terrible play and perfect theater. Half the neighborhood attended. No one checked their phone. For twenty minutes, Hawthorne Street remembered an old magic: we are each other’s weather.

In May, a letter slid under the door in familiar cursive. Susan’s handwriting had honed itself against argument over decades; it looked exhausted now.

Anna,

We are moving to a small apartment near my sister. Steven is looking for work. I am… not well. I wanted to say I am sorry. Not “if.” Not “but.” Just “I am sorry.” You deserve truth. I insisted on comfort. Please give the house what I could not give you.

—Susan

I placed the letter under the candle on Sunday and said her name without the heat. The next day, I mailed her a laminated recipe card in my grandmother’s hand: Chicken soup for stubborn days. Under salt to taste, Grandma had drawn a tiny heart. I added a Post-it: Drink water. Nap twice. —A.

I did not invite her to stay. I did not reopen old rooms for ghosts. Peace doesn’t require returning a key.

When the anniversary of the will came around, Ames brought champagne and store-bought cake with earnest frosting. We stood in the foyer, three women spanning seventy years of Hawthorne Street history. “You did right,” she said, raising a paper cup. “By law and by love.”

I looked at the photo of Pamela on the mantle, then Rebecca beside her, and felt something settle more deeply than a foundation.

“They called it betrayal,” I said, the words steady at last. “I call it justice.”

Ames nodded. “And using peace where fire would have felt so good—that’s something beyond justice.”

“Survival,” I said. “And maybe something like grace.”

We clinked cups. In the kitchen, Mrs. Patel laughed so hard she snorted. In the library, a request for more dragon books echoed up the stairs. The house shifted its weight under me and sighed.

I exhaled a year’s worth of breath.

Part III — The End That Opens

Summer came with its deliberate miracles: tomatoes, thunderstorms, the way twilight stretches the day into a promise and keeps it. The One Who Stayed hosted a block party that turned the street into a small town. Mr. Grier hauled out a grill the size of a Buick. Kids rode bikes in shoals. Someone started a water balloon war that took down the pastor and the alderwoman with equal accuracy. I ran out of paper plates and worry at the same time.

Near dusk, a woman in a suit with court-short hair stood at the garden’s edge, hands in pockets. She watched the stage with the beetle curtain call, then found me by the lemonade.

“You’re Anna,” she said. She held out a card. Dara Collins, Family Court.

My spine tried to climb into my throat. “Did… someone file something?”

She laughed, genuine. “No. I’m here because I heard what you built. We keep telling people to get out of bad houses. We don’t always tell them where to go next.”

“Here,” I said, and was surprised again by how easy the word felt. “Here is good.”

She looked around at the groupings—elders on lawn chairs, teenagers pretending not to care, toddlers sticky with independence—and nodded. “Rebecca would be furious she didn’t think of this first.”

“She did,” I said. “I’m just the one who stayed long enough to read her handwriting.”

Dara walked back to her car. I tucked her card into the cigar box that held practical magic: business cards, spare keys, the list of good plumbers, the first beetle drawing, a photograph of Grandma’s hands teaching mine to thread a needle.

Twilight carried new faces into the yard—friends of friends, curious passersby whose feet had never brought them this far down Hawthorne. A man stopped at the gate and stared up at the house. He was careful with his posture, as if he believed the right arrangement of angles could stave off regret.

“Pretty,” he said to no one in particular, then to me. “I grew up here.”

I looked for recognition, found none. “Your name?”

“Leonard,” he said. “My mother kept house here for Mrs. Sullivan in the eighties. I used to sleep on the back stairs when it got hot.” He smiled at the memory without scab or sting. “There was a cat who hated me. Still is, I hear.”

“There is,” I said. “She hates evenly.”

He didn’t ask to come in. I didn’t invite him. Some homes hold strangers and exiles the same way—tenderly, without claiming. He stood at the gate a long while, then nodded to the house and walked on. The porch light hummed approval.

Late that night, after the last folding chair had remembered how to fold, I sat on the steps with a cup of tea that had lost its heat to the air and didn’t mind. Marco collapsed next to me, grass in his hair, paint on his knees, happiness in his bones.

“You did it,” he said.

“We did it,” I replied.

He tilted his head, thinking. “You know, I used to believe revenge looked like a match,” he said. “Now I think it looks like what you built. A place that makes the people who hurt you irrelevant.”

“Peace can be the loudest revenge,” I quoted, and we both laughed because the line had become a house rule.

The mailbox flag shifted in the breeze. I walked down the path and opened it. A single envelope lay inside, addressed by a hand I knew as well as my own.

My Anna,

You are tired. Put your feet up. Eat the heel of the bread. It has all the butter it wants. Give the cat the last sardine.

I loved you first. I love you still.

—Grandma

I sat on the step and cried in the kind of way that doesn’t break anything.

In the weeks that followed, my life acquired a rhythm that felt like marriage vows to a place: for richer, for poorer; in boiler and in roof; in youth and in kind decline. People asked how I could bear to live inside so much history. I said: “History keeps the porch light on.”

One morning, I took the album to the sewing room. I slid Pamela’s picture from its sleeve and placed it in a new frame. I set it beside Rebecca’s. Two women. Two kinds of courage. One gave me life; the other kept me living. I stood there, a third point in a quiet triangle, and felt the geometry of belonging settle into proof.

In autumn, a letter arrived from the probate court—a final stamped copy of the estate’s closure. Rebecca Sullivan’s wishes executed in full. I held the paper to my chest and imagined handing it to her, imagined her saying, Of course they were. Why wouldn’t they be? Then she’d press toast into my hand and say, Eat. Justice burns calories.

The Bennetts did not return. I heard from someone that Steven found work at a car lot and Susan started growing herbs in a window box and sometimes—rarely—spoke my name as if it could grow, too. I kept their letter in the cigar box with the others. Memory is heavy if you carry it in your fists. In your open hands, it’s just what it is: a story that happened to you and is done.

Winter brought the quiet work of keeping warm. We hosted coat drives and story nights and the kind of potlucks where folktales show up disguised as recipes. A young couple asked to be married in the garden under the old maple that had learned to bend instead of break. We said yes. The pastor spoke, and the beetle took a nap under the stage.

Sometimes I walk through the house before bed, lights out, relying only on muscle memory and moon windows. I touch the newel post smooth as good manners. I listen to the hot water sigh. In the library, I trail my fingers over the spines and feel the hum of strangers who have found themselves home here for an hour or a winter.

What happened to me didn’t end with a verdict or a victory lap. It ended with a decision I make every morning when the kettle boils: Who gets my air today? Not ghosts. Not grifters. Not anyone who would confuse love with leverage. This house gets my air. The people in it get my air. The girl in the photos gets my air. The woman in the mirror gets my air.

They pretended to be my parents, and they were good at pretending. But Grandma’s final words unmasked the truth, and the truth did what it always does when you finally let it in: it rearranged the furniture so the light could find you.

I don’t know if what I did counts as revenge. I know it counts as a life.

I light the Sunday candle. I pour two cups. I set one at Rebecca’s elbow and one at Pamela’s. I take the third for myself and whisper the benediction Hawthorne Street taught me:

“Stay. You’re home.”

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

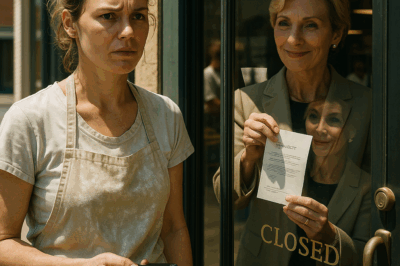

CH2. My Mom Smiled, “YOU SIGNED THIS, ALLISON.” Then Locked Me Out of the Bakery I Built, Until LAWYER…

At 17, My Family Kicked Me Out Over a Lie — Years Later, I Bought the Bakery They Tried to…

CH2. At 17, My Family Kicked Me Out Over a Lie — Years Later, I Bought the Bakery They Tried to Steal.

At 17, My Family Kicked Me Out Over a Lie — Years Later, I Bought the Bakery They Tried to…

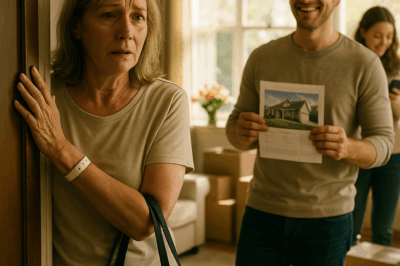

CH2. When I Came Home from Surgery, My Son Smiled and Said, “We’ve Been Helping You, So We Listed the …

When I came home from surgery, my son smiled and said, “We’ve been helping you—so we listed the house.” That…

CH2. My neighbor slipped a note under my door: “leave your house in 10 minutes. Act normal. Trust me.”

My neighbor slipped a note under my door: “leave your house in 10 minutes. Act normal. Trust me.” I went…

CH2. I Was Banned From Mom’s Wedding — She Demanded $5K to Let Me Back In, So I Wrecked Her Honeymoon

I Was Banned From Mom’s Wedding — She Demanded $5K to Let Me Back In, So I Wrecked Her Honeymoon…

CH2. “I’m Choosing Him, But Can We Still Be Friends? You’re My Safety Net,” She Asked — I Deleted Her…

“I’m Choosing Him, But Can We Still Be Friends? You’re My Safety Net,” She Asked — I Deleted Her Number…

End of content

No more pages to load