They Mocked His “Too Slow” Hellcat — Until He Outturned 6 Zeros and Shot Down 4

The sky over Rabaul was on fire.

Tracer lines stitched through black smoke, burning red and white across a canvas of rising flak. Orange blossoms of exploding shells bloomed beneath tatters of cloud. Silver shapes flashed in and out of the chaos—bombers holding grimly to their courses, fighters weaving, diving, clawing for an instant of advantage.

And in the middle of it, a single blue-gray Hellcat was turning where it had no business turning at all.

Lieutenant Commander Edward “Ed” O’Hare hauled the stick into his lap with both hands. The Grumman F6F shuddered, metal skin rippling as invisible fists of air pounded its wings. The Pratt & Whitney R-2800 engine bellowed at full power, eighteen cylinders throwing out heat and fury.

Somewhere above and behind him, six Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters spiraled down through the smoke like white sharks closing in on a wounded whale.

Every manual in the U.S. Navy said the same thing: do not dogfight a Zero.

In every ready room from Hawaii to Guadalcanal, the doctrine was written on chalkboards and drilled into skulls: your plane is heavier, your plane is slower in the turn, your plane cannot dance with that slender Japanese killer.

Dive, strike, climb away.

Hit and run.

Never stay.

Never turn.

But O’Hare wasn’t climbing away.

He was turning into them.

He grunted as the G-forces climbed, as the straps dug into his shoulders, as the airframe groaned like an old ship in a storm. His world shrank to the circle of glass in front of him and the small black dot of a Zero’s nose drifting across it.

The Hellcat’s nose came around just a fraction faster than the Zero pilot expected.

That fraction was all O’Hare needed.

He squeezed the trigger.

Six .50 caliber machine guns erupted, the wings juddering with the recoil. Bright lines tore across the empty air, then converged. The Zero’s fragile skin shredded. Fuel and metal and a flash of fire—then a white-winged fighter that had terrorized the Pacific for two years came apart in midair, trailing burning pieces into the clouds below.

One down.

Five to go.

No one had ever written a manual for what Ed O’Hare was doing now.

He was writing it himself in real time, in the language of smoke and tracers and gravity.

And if that terrified the men who had mocked his “too slow” Hellcat, it terrified the Zero pilots even more.

Two thousand miles away, months earlier, the argument about the Hellcat had started in a place that hardly seemed big enough to hold such questions.

Henderson Field on Guadalcanal was nothing more than a scar of dirt and coral carved out of jungle. At noon it shimmered with heat. At night it shook under Japanese shellfire. The strip smelled of avgas, sweat, hot metal, and something rotten that nobody ever had time to track down.

Under sagging camouflage netting, mechanics worked shirtless, bodies burned brown by the sun and streaked with grease. They coaxed life out of engines that had been asked to do too much, too often, with too little rest. Every so often they’d glance up at the sky as another flight of dauntless SBDs or Wildcats staggered into the air.

Out near the line of revetments where fighters slept beneath palm-frond shelters, a young pilot squinted up at an F6F Hellcat and shook his head.

“It’s a truck,” he said, thumbing toward the bulky fighter. “A flying barn. You strap wings on a safe and that’s what you get. I’ll take a Wildcat any day.”

“Tank with wings,” another pilot agreed, wiping oil from his hands. “You feel it the first time you pull back on the stick. The Wildcat, she answers quick. The Hellcat… she thinks about it.”

A third pilot, lanky and sunburned, shrugged. “She’s got six fifties and armor. I’ll take thinking over catching fire. Zeros sneeze in your direction and the Wildcat turns into a Zippo.”

“Zeros’ll run rings around that thing,” the first pilot said. “If you try to turn with them, you’re dead. Everybody knows it.”

They all turned when they heard the sound of footsteps on coral.

O’Hare approached his Hellcat without saying anything. Twenty-eight years old, lean, face reddened by Pacific sun and cut with lines deeper than his age should have allowed. He moved like a man who knew people were watching him and had long ago decided he didn’t much care.

The younger pilots fell quiet as he passed. Not out of fear.

Out of the peculiar, hushed respect that surrounded anyone who had earned the Medal of Honor and walked away from it.

“Morning, Skipper,” the lanky pilot said, trying for casual.

O’Hare nodded. “Morning.”

He ran a hand along the Hellcat’s wing root, fingertips feeling the rivet lines beneath chipped paint. He didn’t seem bothered by its bulk.

He’d heard all the jokes.

He’d also heard the whispers.

That’s him. That’s O’Hare. The guy from Lexington.

The story had already passed into squadron legend.

Nine Japanese bombers coming in low over a mauled carrier in February ’42. A scrambled pair of Wildcats. One of them with a jammed gun. One pilot—O’Hare—left with enough ammunition and enough time to maybe shoot down one bomber if he was lucky.

He’d killed five.

Five bombers destroyed, three more damaged so badly they never made it home. The carrier Lexington saved.

He’d landed with holes in his plane, his nerves buzzing, and his life changed forever.

The Navy had pinned the Medal of Honor to his chest and the press had turned him into a symbol. They used words like lone avenger, guardian of the fleet, knight of the sky.

O’Hare hated those words.

Not because he wasn’t proud of what he’d done, but because he knew the truth.

That day over the Lexington, he hadn’t relied on heroics.

He’d relied on math.

On fuel calculations. On angles of deflection. On the speed and bearing of enemy aircraft intersecting his own. On how much lead to give a bomber at a hundred knots closing speed.

The medal sat in a box. The equations lived in his head.

Now, staring at the Hellcat, he was thinking through another set of equations entirely.

Weight. Wing area. Power. Turn rate. Energy retention at 200 knots, 250, 300. Where the aircraft stalled. When it shook. How it rolled.

The other pilots saw an overweight replacement for their beloved Wildcats. Something designed by committee.

O’Hare saw something else.

A problem to be solved.

Or maybe an answer waiting for the right question.

Years before he ever felt the weight of a flying tank under his hands, Edward Henry O’Hare had learned what it meant for life to change with one decision.

He’d been born in 1914 in St. Louis, Missouri, into a house full of contradictions.

His father, “E.J.” O’Hare, was a lawyer who moved in dangerous circles—representing Al Capone’s interests in grey areas where money blurred the law. There were cars with shiny fenders and nights filled with the clatter of dinner parties.

There was also his mother—devout, disciplined, determined that her son would grow up straight in a crooked world.

Edward learned early how to read people. When grown men sat in his father’s study and lowered their voices, he listened from the hallway, memorizing tones more than words.

He liked puzzles. Mechanical toys fascinated him. He’d take apart watches and put them back together, not because he wanted to break them but because he needed to know how gears and springs made something as mysterious as time visible.

In 1931 his father made a choice that changed everything.

E.J. O’Hare turned informant against Capone.

He provided evidence to the federal government, helping build the case that would finally bring the Chicago boss down on tax charges.

Everyone in the family understood what that meant.

Loyalty in that world was a one-way street. There were no graceful exits.

A week before Capone’s trial, E.J. O’Hare was found slumped over the wheel of his car, shot to death. The case was never solved in a way that a court of law would accept.

In the court of a teenage boy’s mind, the verdict was simple.

Actions had consequences.

Edward didn’t talk much about his father after that. He carried the lesson instead.

You don’t get to choose the rules of the game, he thought. You only get to choose whether you understand them.

In 1933 he entered the Naval Academy at Annapolis.

His classmates remembered him as quiet, steady. Not the loudest voice in the room. Not the daredevil. The guy who always had his navigation problems done correctly, who could explain the math if you bothered to ask.

He wasn’t a “natural” stick-and-rudder pilot when he moved on to flight training. He wasn’t the guy doing snap rolls at ten feet to impress the girls on the beach.

What he was, even then, was methodical.

He’d fly the syllabus, then stay a little longer in the hangar, asking questions about fuel flow or engine temperature curves. He’d sit with a chart and a slide rule, calculating fuel consumption at various altitudes, then go up and see if his numbers matched the gauges.

Flight instructors wrote in his file: calm under pressure. Good judgment. Excellent at gunnery and navigation. Thinks ahead.

When war burst over Pearl Harbor, O’Hare was no rookie. He was a carrier aviator with hundreds of hours in Wildcats, well versed in the realities of flying over open ocean with a finite amount of gas and an unforgiving horizon.

He knew that courage was worthless without calculation.

You could be brave all day long.

If you misjudged how far your aircraft could go on a half-full tank, you’d die bravely somewhere in the dark without anyone to see it.

The Lexington mission in February ’42 had proved to him that the math and the instincts could coexist.

Now, late in 1942, as he strapped into the F6F Hellcat program, he approached the new fighter the same way he’d approached everything else.

Not with awe.

With curiosity.

The pilots who first transitioned to the Hellcat from the nimble F4F Wildcats joked that they’d been promoted from a sports car to a truck.

“You don’t fly it,” one of them said at Guadalcanal. “You persuade it.”

They were half right.

Compared to the wispy Zero, the Hellcat was a brute.

It weighed over two thousand pounds more than its Japanese counterpart. Its wings were thicker, its fuselage broader. It carried armor behind the pilot’s seat, self-sealing fuel tanks in its belly, and six .50 caliber Browning machine guns in its wings.

Where the Zero had been built like a racing bicycle, all steel tubing and cloth and just enough strength to hold together if no one knocked on it too hard, the Hellcat had been built like a boxer—thicker-boned, slightly slower on the pivot, but capable of taking punches all day and still swinging.

On the chalkboard, the comparison was simple.

Zero: lighter, tighter turn radius, superior maneuverability at low speed, but fragile. No armor, tanks that erupted when hit, no self-sealing, control surfaces that stiffened at high speed.

Hellcat: heavier, slower in the climb, larger turn radius at low speeds—but rugged, forgiving, fast in a dive, able to hold high-speed turns without falling apart.

But no pilot flew on chalk.

They flew on habit and doctrine.

The early Pacific doctrine had been written in blood during the worst days of 1942. When American flyers first met the Zero in Wildcats, they’d discovered the hard way that trying to turn with it at low speeds was suicide. The nimble Japanese fighter would simply tighten the circle and rake them with 20mm cannon.

So the Americans adapted.

Boom and zoom.

Dive from altitude, blast through the fight, fire a burst, climb away. Use your speed, not your turning circle.

It was good doctrine.

It kept people alive.

It also turned the Zero into the pace car.

You were always reacting to its moves, always in a hurry to get away because you were convinced that if you stayed too long, you’d die.

When the Hellcat arrived in mid-1943, it inherited that doctrine—warts and all.

Pilots climbed from Wildcats into the bigger F6F and tried to fly it the same way.

Some complained it couldn’t climb like the Zero.

Some complained it felt sluggish in the turn.

Ed O’Hare flew it and took notes.

He didn’t just take notes on how it failed.

He took notes on where it didn’t.

He flew it clean, light on fuel and ammo, then heavy, with drop tanks and full guns. He flew it up to stall and beyond, feeling the chatter in the stick before the nose dropped. He rolled it at different speeds, counting how long it took to bank ninety degrees, one-eighty, three-sixty.

He fought mock duels with squadron mates in Wildcats pretending to be Zeros and with captured Japanese aircraft evaluated by test squadrons.

Slow turns?

Yes, the Hellcat bled energy there. The Zero would crawl around your inside like a hungry spider in a jar.

But high-speed turns?

That was another story.

At 250 knots and above, the controls stiffened—but they stiffened in a way that still allowed precise input. The wings bit the air without shuddering. The big engine had enough grunt to keep the nose coming around if you knew just how much to ask and just how much to give it in throttle.

The Zero, at those speeds, didn’t feel so magical.

Its light controls became too light, its structure complained, its wings felt like they were sawing at the air rather than cutting it.

The Hellcat could roll faster in a vertical plane. It could dive, reverses its bank, and claw back upwards with an engine that loved to haul heavy things.

“The Hellcat can’t outturn a Zero,” one of O’Hare’s fellow pilots said over coffee one sticky afternoon.

“Not at 180 knots,” O’Hare agreed mildly. “At 260? That’s a different question.”

The pilot snorted. “You’re not going to be fighting at 260 in a furball. Not if the Zeke has his way. He’s going to drag you down into his world.”

“Then don’t go,” O’Hare said.

“Sometimes you don’t have a choice.”

O’Hare looked at him for a moment, then shrugged.

“Sometimes you do,” he said. “And sometimes you can give him an invitation to yours.”

That was the beginning of what he came to think of as his private theorem of air combat:

You cannot change what your airplane is.

But you can change the fight.

At night, in the dim light of the ready room, he’d sit with a pencil and scribble lines on scrap paper—circles within circles, arrows showing vectors, energy states imagined as concentric shells around an invisible Hellcat holding or shedding speed.

He wasn’t trying to prove the Hellcat could outdo the Zero at everything.

He was trying to prove there was at least one corner of the sky where the Zero did not own the rules.

By February 1943, the Air War in the Solomons felt like a question mark written in smoke.

Every day, American and Japanese aircraft clashed above green islands and blue water, and no one was quite sure yet which side would own the sky when the smoke cleared.

The Japanese had started the war with a qualitative edge—better fighters, better-trained pilots, tactics honed over years of combat in China. Their Zeroes could circle tighter than anything the Allies could put up, and their early victories had been dramatic enough to terrify.

By early ’43, the balance had begun to tilt.

New aircraft like the Hellcat and the F4U Corsair were emerging. American training programs were churning out pilots, and the ones who survived their first missions learned fast. Radar was making its presence felt in the Pacific, guiding intercepts, warning of raids.

And on Guadalcanal, at Henderson Field, men like Ed O’Hare were strapping into these new machines and taking them into the crucible.

The field itself never let them forget how precarious their situation was.

Shell craters pocked the coral runway. Each night, Japanese destroyers, the “Tokyo Express,” would come in close enough to lob shells at the airstrip, shaking tents and sending men diving for shallow foxholes.

The Americans called their tents “coffins” half-jokingly and slept in them with boots on, ready to run when the shelling started.

In that world, sleep was a loan from the future, never an investment.

On the morning the Rabaul raid was briefed, O’Hare woke to the sound of rain hammering canvas and the faint, constant murmur of men trying to keep nervous chatter from turning into something louder.

He rolled from his cot, tugged on a flight suit that crackled with dried salt and dust, and stepped out into red-brown mud. The rain had tamped down the ever-present dust just enough for the air to smell like wet earth and fuel instead of just fuel.

Inside the briefing tent, the mood was tight.

A map of the Bismarck Archipelago took up one wall, Rabaul circled in red pencil. Weather notes, fuel charts, altitude brackets, radio frequencies. Someone had drawn a little skull and crossbones near the target.

“Rabaul,” the briefing officer said, tapping the circle. “Home to enough Japanese aircraft to ruin your whole day. This is a fortified base cut into volcanic ridges and jungle. You’ve got heavy flak, experienced fighter pilots, and no place to ditch between here and there except the ocean.”

He let that sink in.

“Today’s menu is simple,” he went on. “Sixteen bombers, escorted by eight Hellcats. Targets are fuel dumps, supply depots, and runways. You’re to keep Zeros off their backs long enough for them to make their drops. Do not get cute. Stay in formation, stay disciplined. You are not there to chase personal glory.”

He looked at O’Hare for just a fraction of a second, then moved on.

Everyone in the room felt the glance.

O’Hare ignored it.

He studied the lines on the map.

Rabaul meant flying hundreds of miles over open ocean, with no radar coverage past a certain point, no search and rescue if you went into the drink. If you got hit over the target and lost an engine or began leaking fuel, you were, statistically speaking, already dead.

He scribbled numbers in his own notebook as the briefing moved on.

Cruising speed. Fuel consumption. Climb gradients to get the bombers to altitude. Time over target.

When the weather section came up, he listened carefully.

Clouds over the approach. Broken layers near ten thousand. Good—cover for the bombers, maybe. Or traps where Zeros could loiter unseen.

He didn’t ask many questions.

He’d learned early that asking made people either nervous or defensive. Better to listen, and observe, and do his thinking where no one could see it.

After the briefing broke up, he walked out toward the line.

The Hellcat waiting for him wore the scars of previous missions: paint scuffed by salt air, patches where bullet holes had been repaired, oil stains on the deck beneath its belly.

A crew chief met him with a clipboard.

“Morning, Commander,” the chief said. “Bird’s topped off. Ammo checked. We fixed that slight misfire on your number-three gun.”

“Thanks,” O’Hare said. He ran through his preflight with deliberate care, hands feeling each surface, each hinge.

He paused by the leading edge of the left wing, feeling the curvature.

This is where the air hits you first, he thought. This is where the fight starts.

In the corner of his eye, he saw a few of the younger pilots watching him.

One of them, the same lanky pilot who’d joked about Hellcats being trucks, stepped closer.

“Skipper,” he said, “this thing really going to keep up with Zeros over Rabaul?”

O’Hare looked at him.

“I don’t need it to keep up with them,” he said. “I need it to keep them busy. The bombers don’t care who the Zeros are turning with, as long as it’s not them.”

The pilot smirked, but the expression didn’t quite reach his eyes.

“Just don’t start doing any of your hero stuff, sir,” he said. “I’ve seen the picture in Life magazine. I’d rather you stay in one piece.”

“Me too,” O’Hare said.

He climbed the ladder into the cockpit and settled into the seat. The instrument panel looked back with its familiar cluster of dials and gauges. He buckled his harness, adjusted his oxygen mask, and glanced once at the small photo taped beside the panel—a family picture, edges curling in Pacific humidity.

Then he hit the starter.

The R-2800 coughed, sputtered, then roared, wobbling the entire airframe. Vibrations came up through the seat, through his spine.

He loved that sound.

It was raw, unapologetic power. The sound of a machine that didn’t need to prove it belonged in the air. It simply assumed it.

Propellers blurred, sending ripples across puddles of standing water near the revetments.

One by one, other Hellcats and bombers came to life.

The formation taxied toward the runway in a staggered line.

As they lifted into the sky and the battered strip fell away beneath them, Guadalcanal shrank to a strip of green and brown in a vast expanse of blue.

O’Hare settled into his place in the escort formation, eyes scanning the sky ahead, mind already dividing the universe into fuel, altitude, friendlies, and threats.

Somewhere beyond the horizon, Rabaul waited like a hornet’s nest.

Somewhere, the Japanese early-warning net was already talking about them.

On the other side of that horizon, in the jungles and hills around Rabaul, the Japanese had turned a tropical paradise into a layered fortress.

Rabaul’s airfields lay tucked into volcanic valleys, camouflaged revetments cut into hillsides. Tunnels bored into the rock housed fuel, ammunition, aircraft parts. Anti-aircraft guns peered from hidden nests.

Coastwatchers—Japanese soldiers posted on the outer islands, and local sympathizers—watched the sea and sky and relayed sightings over crackling radios.

When the American formation crossed the invisible line where ocean became threatened airspace, the news was already moving through Japanese circuits.

Enemy bombers, one observer reported. Approximate altitude. Approximate heading.

At a cramped command post near Lakunai airfield, a Japanese air operations officer smoked a cigarette down to the nub as he studied his own map.

“Launch interceptors,” he said. “We will greet our guests.”

Sirens wailed.

Zero pilots ran.

In ready huts nearby, men who wore the white hachimaki cloth of Japan’s pilots grabbed flight gear, pulled on leather helmets and goggles. Some had been in the war since Pearl Harbor and before, veterans of China and the early Pacific campaigns. Others were newer, replacements trying to fill shoes that no one could really fill anymore.

One such pilot, Lieutenant Sato, tugged on his gloves and ran toward his waiting A6M Zero.

On paper, the Zero was already outclassed by newer American fighters.

On the ground, Sato didn’t feel outclassed.

He remembered his training flights where the Zero seemed able to carve any turn he asked of it, to hover on the knife edge of stall without falling. He remembered lectures about the boldness of Japanese spirit, the weakness of American decadence.

He climbed into his cockpit, strapped in, and felt the controls settle under his hands like an extension of his own body.

His plane couldn’t take much punishment if it was hit.

Simple solution.

Don’t get hit.

He was good at that. So far.

Engines shrieked as Zeros rolled down the airstrip and bounded into the sky.

Sato joined his section, sliding into position on his leader’s wing. Six Zeros formed into two three-plane V’s and climbed toward a patch of sky where black dots were growing larger.

He took one last breath of warm tropical air, then focused.

He’d never heard of Ed O’Hare.

He was about to learn his name, in a way.

Or at least remember the day he met a Hellcat that didn’t behave like it was supposed to.

The approach to Rabaul felt like a corridor narrowing around O’Hare.

The ocean that had been a calm slate beneath them began to be cut by islands—green humps of land ringed with white surf. Clouds thickened, forming stacks like distant mountains.

The bombers tightened their formation. Their engines beat a slow, steady rhythm, the silver birds stubbornly wading into what everyone knew would be a killing ground.

The first bursts of flak appeared as sooty puffs in the distance. Then more, closer, filling the sky ahead with black blooms.

“Here we go,” O’Hare muttered.

“Stay tight,” came the voice of the bomber leader over the radio. “Let’s make this count.”

The Hellcats shifted closer to the bomber boxes, weaving above and to the sides, scanning for fighters.

Flak grew thicker. Hot wind from near misses thumped against the fuselage, rattling the cockpit. Shrapnel whined past.

Through the dirty canopy glass, O’Hare saw the target area—runways, revetments, fuel dumps.

“Bombs away in ten,” someone said.

He didn’t answer.

He was looking higher, above the flak, into the clear air where dots moved like insects at the edge of vision.

Zeros.

“Bandits twelve o’clock high!” someone shouted.

They came in flights of three and four, as expected. Diving from the sun, wings glinting white, then dark, then white again as they rolled and dove.

The sky that had been just flak and cloud became a three-dimensional maze of contrails and crossing vectors.

Bombers held their courses.

That was courage, O’Hare thought. Flying straight and level in this soup.

The Hellcats broke to meet the incoming.

“All fighters free to engage,” came the order.

O’Hare saw the first pass—Zeros ripping through the formation, cannons spitting, tracers lancing into a B-25’s wing. The bomber rolled, struggling, then slid out of formation trailing fuel and fire.

He wanted to go after the attackers, to kill them before they could climb and come again.

But his job today wasn’t to chase.

It was to guard.

He forced himself to look for the gaps.

There, to the right, a bomber lagging behind, engines straining, smoke pulsing from one nacelle. Its formation had unconsciously tightened away from it, the proximity of flak making them press together like frightened animals.

And behind that wounded bomber, like wolves homing in on weakness, came six Zeros.

He saw them in the turn of his head, as one coherent picture.

Six enemy fighters. High, closing, line astern. One crippled bomber with a silent tail gun—he could see the gun slump, unmanned or smashed.

He did the math.

Time to intercept? Seconds.

Distance? A few thousand yards closing at combined speed that made time feel condensed.

He looked left and right for friendly fighters.

Too far.

“Hellcat Three to all fighters,” he snapped. “Bogey flight on the lagging bomber, I’m engaging.”

There was no time to wait for acknowledgement.

He shoved the throttle forward to the firewall.

The R-2800 roared, the Hellcat surging as though someone had kicked it in the back. O’Hare pushed the nose down and dove.

Airspeed climbed: 240, 260, 280 knots.

The stick grew heavier in his hand, but not unmanageable.

He felt the aircraft gather itself into the kind of high-speed, high-energy state he knew he needed.

The wounded bomber grew in his windscreen, the markings on its tail resolving out of the murk. The six Zeros behind it separated into individuals—sleek fuselages, rising, closing.

He picked the trailing one.

Always kill from the back forward.

He led it by a hair, just enough to put the Zero where it would be, not where it was.

He squeezed the trigger.

Six .50 cals spat red streams of fire. The guns thundered in his wings, the smell of cordite flooding the cockpit.

Bullets stitched across the Zero’s wing root and cockpit. One second it was a coherent machine; the next it was a cloud of fragments, fuel, and flame. A wing snapped, spinning away like a discarded toy. The fuselage tumbled, trailing black smoke.

Five Zeros left.

If doctrine had been sitting in his back seat, it would have been shouting at him about now.

Break away. Climb. Don’t turn with them.

He might have listened, if the bomber below hadn’t still been alone, still smoking, still staggering for home.

He might have listened, if he hadn’t spent weeks flying this “too slow” Hellcat the way no one had taught him.

Instead, as the remaining five Zeros flared out and broke into a climbing turn to engage, Ed O’Hare did the most dangerous thing he’d done since the day he saved Lexington.

He pulled the Hellcat into a turn to meet them.

The G force hit him like a fist. Blood tried to drain from his head. The world narrowed, the edges of his vision turning gray. He clenched his stomach muscles and grunted, forcing the blood back up.

“Come on, you fat lady,” he growled to the Hellcat. “Dance.”

She did.

Not elegantly. Not with the quick, light-footed steps of a Zero.

But with a strong, sweeping arc that kept speed on the clock.

The Zeros tried to do what they always did: tighten the circle, get inside the opponent’s turn.

At 200 knots, they’d have sliced inside him easily.

But they weren’t at 200.

O’Hare kept his Hellcat above 250, throttle still firewalled, nose coaxed carefully through the arc without letting it wash too far above the horizon.

The heavier aircraft bit the air in a way that surprised the Japanese pilots. Their own planes, lighter and built for agility, began to feel… mushy.

Lieutenant Sato, eyes narrowed behind his goggles, pulled back on his stick, trying to drag his Zero’s nose inside the big American fighter’s turn. The controls, so light and responsive at lower speeds, were now stiff. The airframe shuddered a warning.

He realized with a jolt that if he pulled harder, his wing would stall. Or worse.

This American is turning too fast, he thought.

That wasn’t supposed to happen.

O’Hare felt the same thing from the other side—that minute difference between turning tighter and turning faster.

He didn’t need to be inside their circle.

He needed to get around it quicker.

He reversed.

He rolled the Hellcat slightly, pulled the nose through the vertical plane, trading a bit of altitude for more airspeed, turning the circle into a spiral. The engine’s roar deepened as gravity lent a hand.

The Zeros followed instinctively, trying to match the spiral.

But in that brief dive, their delicate balance of lift and drag went off-kilter.

They had bled speed in the initial hard turn, trying to tighten the circle. Now, forced into a vertical maneuver at lower energy, they floundered.

“Now,” O’Hare breathed.

He snapped the Hellcat back into a climbing turn, using the R-2800’s power to claw upwards and around. The Gs dug in again, but the airframe held.

In his gunsight, another Zero’s nose drifted across.

He fired.

The second Zero bucked as bullets tore through its fuselage. Smoke gouted from its engine. It rolled half-heartedly, then fell off into a spinning dive trailing a black curtain.

Four left.

Tracer rounds flashed past O’Hare’s canopy, so close he could see the smoke trails.

He yanked the stick, feeling the big fighter shudder, then steadied. He’d felt the Zero’s bullets close enough to smell them, but they hadn’t found skin.

Lieutenant Sato saw the Hellcat roll and cursed under his breath. The American had just dodged a burst that should have cut him in half. Sato adjusted, trying to anticipate the turn.

But the American wasn’t turning slow.

He was snapping, reversing, converting altitude into speed and speed back into altitude with a kind of brutal efficiency Sato wasn’t used to seeing from these fat Grummans.

The fight tightened.

For a few seconds—or maybe it was minutes, time lost meaning—there was only a swirling carousel of machines in a three-dimensional knot in the sky.

The bomber they’d first been hunting limped away, shrinking in O’Hare’s peripheral vision, its gunner probably staring back at the duel in disbelief.

At one point, a Zero juked across O’Hare’s nose, a flash of green and red sun disk.

He fired a snap burst, more instinct than calculation.

Bullets slashed across the Zero’s fuselage and wing root again. It jerked, tried to correct, then its nose dipped. The pilot must have been hit. The aircraft dropped like a stone.

Three left.

At some point, O’Hare stopped counting consciously.

He simply responded.

He felt the subtle buffeting of air over wings, the whisper of slip that told him he was pulling too hard, the heavy but trustworthy resistance of the Hellcat’s controls at high speed.

He kept it all on the edge of controllable.

He refused to give away energy.

Let them bleed theirs, he thought. Let them claw for a tighter turn and find nothing but drag.

His world shrank to inputs and outputs. His body was just another sensor in the system. His legs and hands moved like he’d rehearsed this fight a thousand times. In a way, he had—on those random nights with scrap paper and a pencil.

He saw one Zero tighten too much, its inner wing starting to dip.

You’re going to stall, he thought. You just don’t know it yet.

He eased off his own pull just a hair, letting the Hellcat shoot slightly ahead, then rolled and reversed into the inevitable overshoot.

The Zero slipped outward, its pilot suddenly realizing his mistake as the stall bit harder.

O’Hare dropped the nose, rolled behind him, and fired a sustained burst.

This one came apart more cleanly than the others, the wing snapping, fuel spilling, flame blooming.

Four.

The last two Zeros, seeing the fight’s momentum shift, broke off. One hauled into a climb, trying to get above and reset. The other peeled away, angling toward a cloud bank.

O’Hare felt a primal urge to chase.

He cut it off.

He let them go.

He took a breath that burned going into his lungs and glanced back.

The bomber he’d thrown himself into this insanity to protect was still there. Damaged, coughing, but level.

He turned the Hellcat underneath it, slipping into an escort position.

“Hellcat Three to Bomber Two-One,” he called over the radio. “You’ve got a guardian angel today. How’s your ride?”

There was a pause, then a strained voice, tinny with static.

“Could be better,” the bomber pilot said. “But I’ll take it. Who the hell was keeping those Zekes busy?”

O’Hare looked around at the Zeros just now being engaged by other American fighters, the empty sky where four had fallen.

“Nobody special,” he said. “Just a slow Hellcat.”

He formed up.

They turned away from Rabaul and headed back toward Guadalcanal, leaving behind smoke, burning planes, and a sky that owed its relative quiet to the odd fact that a big, heavy fighter had just done what everyone had said it couldn’t.

The debriefing room at Henderson was an oven.

The thin walls trapped the afternoon heat. The air inside smelled of sweat, coffee, and the metallic tang of spent shell casings that clung to flight suits and hair.

Pilots sat on rough benches, some still in their harnesses, faces streaked with grime and salt. An intelligence officer stood at the front, chalk in hand, a crude diagram of the Rabaul area scribbled on a board behind him.

“Start from the IP,” he said to the bomber leader. “Ingress altitude, enemy opposition, bomb release. Then we’ll move to fighter cover.”

The bomber crews talked first. They described flak so thick you could walk on it, Zero attacks that had torn into their formation, hits, misses, one plane that hadn’t come back.

Everywhere in their narrative, a thread appeared, thin at first, then thicker.

Something about a Hellcat that had appeared behind a straggler like an avenging ghost, tying up Zeros long enough for bombs to fall and damaged engines to keep turning.

When the fighters’ turn came, the intelligence officer turned to O’Hare.

“Commander?” he said. “Walk us through what happened with that trailing bomber.”

O’Hare sat forward, resting his elbows on his knees.

“I saw a bomber drop out of formation,” he said. “Starboard engines smoking. Tail gun was silent. Six Zeros were moving to cut him off. I was the closest fighter. I engaged.”

“How many Zeros did you see?” the intel officer asked.

“Six,” O’Hare said.

“How many did you claim?”

O’Hare hesitated, frowned slightly, as if trying to match mental film to words.

“I saw four go down,” he said. “One exploded. Two trailed smoke and fell. One broke up. The other two disengaged and dove into cloud cover.”

The room murmured.

Four kills, in one engagement, outnumbered six to one, in a plane that everyone said couldn’t win a turn fight with a Zero.

“How close were you to the bomber?” the intel officer said.

“Close enough to ruin both our days if I missed,” O’Hare said dryly. A few pilots snorted laughter.

“Describe your maneuvering,” the officer pressed.

O’Hare shrugged. “Kept my speed up,” he said. “Didn’t let them pull me down below two-fifty. Used vertical and reversed my turns when they started tightening. They tried to cut inside me, but they shed energy doing it. I kept mine.”

The younger pilot who’d doubted the Hellcat earlier raised a hand.

“You’re saying you outturned them, sir?” he asked. “In a Hellcat? Six of them?”

O’Hare looked at him.

“I turned faster,” he said. “Not tighter. There’s a difference.”

The younger pilot frowned. “Feels like splitting hairs when you’ve got cannon shells chasing you.”

“Split hairs start bullets away from your cockpit,” O’Hare said. “Works for me.”

The intelligence officer, sensing the undercurrent, stepped back.

“Skipper,” he said, “can you break it down? For the record. What did you do differently from standard doctrine?”

O’Hare rubbed a hand over his face. He was tired, and trying to put into words something he’d felt in his bones.

“Doctrine says don’t dogfight Zeros,” he said. “That’s still good advice. If I’d had clean altitude and no bomber to protect, I’d have hit them in a boom-and-zoom and climbed away. But that bomber was dead meat if I did that. I didn’t have time for a textbook.”

He leaned forward.

“So I asked a different question: ‘Can I make them fight in a regime where their airplane isn’t as magical?’ That meant speed. The Hellcat doesn’t like slow, flat turns with a Zero. But at high speed, with vertical maneuvers, she holds her energy better than most people think.”

“Most people think she’s a pig,” someone muttered.

O’Hare nodded. “Pigs don’t climb like that,” he said. “You’re calling names because you’re asking her to be a Wildcat. She’s not. Stop trying to fly her like one.”

He looked at the intel officer.

“You want a formula?” he said. “Don’t let your Hellcat bog down in a flat turn below two-fifty knots with a Zero on your tail. Use the throttle. Use altitude. Reverse when he expects you to keep the circle going. Make him bleed speed. Then hit him when he staggers in the turn.”

The room was quiet. Even the skeptics were listening now, if only out of professional self-preservation.

“Sounds like suicide,” an older pilot said. “You misjudge by ten knots, he’s inside your circle with his nose up your tailpipe.”

O’Hare shrugged again.

“You misjudge by ten knots trying to boom-and-zoom and you sail right past him and he’s on your six anyway,” he said. “Everything up there is a bet. I’m just picking the table that gives me better odds in a bad hand.”

After the official debrief broke up, the room emptied in clumps.

Some pilots went straight to their tents and sleep. Others drifted to the mess. A small knot gathered around O’Hare near the doorway.

“Skipper,” the lanky pilot said, “you really think this big bus can be flown like that and live?”

“I don’t know about ‘bus,’” O’Hare said, “but she can be flown smarter than we’ve been flying her.”

“Teach us,” another pilot said quietly.

O’Hare nodded.

“Tomorrow,” he said. “Before the afternoon sortie. We’ll go up and I’ll show you what the stall feels like at different speeds, what the turn rate looks like on the ground if you keep the throttle in. That sort of thing.”

A veteran Wildcat pilot snorted, half-amused, half-skeptical.

“Next thing you know, you’ll have some poor kid trying your Rabaul stunt and getting himself killed,” he said.

“Maybe,” O’Hare said. “Or maybe he’ll get someone else home alive.”

That was always the equation, in the end.

Risk versus reward.

You could write doctrine that protected the average and doomed the exceptional. Or you could teach the exceptional to think harder and hope the average came along for the ride.

The difference, O’Hare suspected, was survival curves measured over dozens of missions and hundreds of men.

And in a war like this, curves mattered.

In the weeks after Rabaul, O’Hare didn’t suddenly turn into a lecturer. He wasn’t that sort of man. He didn’t like the sound of his own voice enough to become a walking doctrine manual.

Instead, he taught in handfuls.

A flight up at dusk with two younger pilots where he’d say, “Okay, watch my wingtip and feel what happens when I pull to here at two-fifty, and here at two-hundred,” then demonstrate the difference between a controlled high-G turn and a mushy, energy-bleeding wallow.

A chalkboard talk in a tent during a rainstorm, where he’d sketch a circle and then another, slightly larger circle around it and say, “This is the Zero at low speed; this is us. He’s inside. Now, here”—he’d draw a larger circle with a smaller circle inside it—“this is high speed. Who’s inside now?”

A casual remark in the mess line when someone mentioned how dangerous Zeros were.

“Yeah,” he’d say. “Unless you make them fly where they’re unhappy. Everything’s dangerous if you fight it where it’s strong.”

Some of the older hands rolled their eyes.

They’d survived this far by not taking unnecessary chances. To them, deliberately tangling with Zeros—even with a new bag of tricks—smelled of reckless overconfidence.

“You’re going to get some hotshot kid killed,” one of them told O’Hare outright on an evening when the rain pounded the tent roof so hard it drowned out conversation.

O’Hare stirred his coffee.

“Probably,” he said. “And if I don’t tell him anything, he might get killed anyway and take his wingman with him because he didn’t know there was any option except running.”

He looked up.

“Kid’s already taking off tomorrow,” he said. “The question isn’t whether he’s going to fight. It’s whether he has more tools in his kit when he does.”

The older pilot had no good answer to that.

Neither did anyone else.

In the end, results spoke louder than arguments.

Pilots who tried O’Hare’s energy tactics in controlled circumstances began to report back that the Hellcat felt different when treated as a high-speed, vertical fighter instead of a plodding horizontal one.

“Zero still turns inside me at slow,” one pilot said. “But up around two-sixty, I rolled and reversed and he slid overshoot just like you said. Scared the hell out of both of us.”

“Did you live?” O’Hare asked.

“Yeah.”

“Did he?”

“No.”

“Good.”

Word filtered upward.

Training officers on the carriers and at stateside facilities started asking pointed questions about the Hellcat’s high-speed behavior. Flight tests were run, charts updated. Tactics bulletins were drafted that began to incorporate language about energy management rather than just “don’t turn with a Zero.”

O’Hare wasn’t the only pilot thinking along these lines.

But he was one of the first, and one of the few with a Medal of Honor on his chest and fresh kills in his log book to back it up.

That combination had a way of getting people’s attention in the Navy.

By late 1943, as the war’s center of gravity shifted toward the Central Pacific, O’Hare found himself no longer just a pilot.

He became a commander.

The USS Enterprise, Big E, had already carved its own legend in the early years of the war. Now, poised to strike the Gilbert Islands in Operation Galvanic, she needed every advantage she could muster.

O’Hare was selected as CAG—Commander, Air Group.

The job wasn’t just about leading individual sorties.

It was about weaving fighters, bombers, torpedo planes, and new technologies like radar into a coherent web of offense and defense.

If he’d been the kind of man who liked seeing his name in headlines, he might have basked in the attention.

Instead, he thought about how many moving pieces there were, and how little time he had to help shape them.

By then, the Hellcat was proving itself beyond any argument.

Production numbers were climbing. Squadrons transitioning to F6Fs from tired Wildcats and SBDs reported kill ratios that seemed almost unbelievable—dozens of Zeros, Vals, and Betty bombers falling for every Hellcat lost.

Pilots who had once mocked the plane now spoke of it with a kind of rough affection.

“She’ll bring you home,” they said. “She’ll take the hits and keep going.”

The numbers told the story:

By mid-1944, Hellcats would account for nearly three-quarters of all Navy air-to-air victories, with a kill ratio against the Zero on the order of 13 to 1.

But numbers were always written after the fact.

In late November 1943, on a dark night in waters not far from Tarawa, Ed O’Hare strapped himself into a Hellcat for what would be his last mission—not to dogfight over a sunlit battlefield, but to chase shadows over black water.

Night fighting in 1943 was more art than science.

Radar was in its adolescence, powerful and promising but temperamental. Airborne intercept controllers sat before green-glowing scopes, talking pilots onto blips that might be enemy bombers, friendly planes, or weather.

Visual cues—horizon, cloud outlines, even the glint of moon on water—disappeared once you were a few thousand feet up. One wrong bank without reference, and you could spiral into the ocean without realizing you were descending.

On the night of November 26, radar aboard U.S. carriers in the Gilbert Islands region picked up inbound Japanese aircraft.

“Torpedo bombers,” someone said.

Betty bombers, twin-engined, capable of low-level attacks that could rip open even heavily armored ships.

The fleet was tired.

The invasion of Tarawa had been brutal. Marines bled on beaches while naval guns hammered Japanese positions. Pilots flew sortie after sortie in support, often in marginal weather and under heavy ground fire.

The last thing anyone wanted now was a torpedo strike slipping through the night.

O’Hare, as CAG, didn’t have to fly that night.

He did anyway.

“This is new ground,” he said in the ready room, leaning over a crude diagram of vectoring patterns. “We’ve trained for it, but there’s no substitute for doing it. If we can make this work, it changes how we defend the fleet.”

He’d been pushing hard for night fighter tactics—combining radar-equipped Avengers and Wildcats (and now Hellcats) in hunter-killer teams to intercept incoming raiders before they could find the carriers.

It was an extension of the logic that had guided him since Lexington.

Understand the system.

Find the leverage.

Change the rules.

He pulled on his flight gear, straps and buckles feeling heavier in the dim red light.

A younger pilot, slated to fly as his wingman, watched him with a mixture of awe and worry.

“Commander,” the kid said, “you sure you don’t want to let one of us take this one?”

O’Hare shook his head.

“If I’m going to ask you to do it,” he said, “I better be willing to do it myself.”

He climbed into his Hellcat, the darkness around the carrier punctuated by small pools of light and the ghostly glow from the sea.

“Laredo One,” the radar controller’s voice came over the radio as three fighters lifted off, one of them O’Hare’s. “We have bogeys bearing two-seven-zero, range thirty, angels three. Vectors to follow.”

The night swallowed them.

The Hellcat’s instrument panel glowed faintly. The only other visible light came from the bluish tongues of exhaust flame licking along the engine cowling.

O’Hare kept his eyes mostly inside the cockpit, trusting his instruments. Outside, the sky was a black void.

He listened to the radar controller’s calm voice.

“Laredo One, turn left to heading two-six-five. Bogeys now range twenty.”

He turned.

Sweat trickled down his back despite the cool night air. Fatigue made his body heavier, but his mind felt sharp.

Somewhere out there, Japanese pilots were doing their own version of the same thing—flying into darkness, guided by whatever navigation aids they had, hoping to find a carrier silhouetted against the sea.

“Laredo One, bogeys now range ten, slightly low, dead ahead,” the controller said. “You should be able to pick up exhaust.”

O’Hare leaned forward, peering into the darkness.

A shadow. Then another. Faint, darker shapes against the night.

There.

“Contact,” he said. “Visual. Closing.”

He shoved the throttle forward.

The distance shrank.

He came in behind and slightly below the nearest shape. At this range, he could make out the silhouette—a twin-engined bomber, Betty type.

He raised his nose just enough to bring the bomber into his gunsight.

He fired.

The tracers were the only bright color in the world for a moment, slicing into the bomber’s belly and wing root. The Betty erupted, an instant sun blooming in the dark. The blast of heat and force rocked O’Hare’s Hellcat, the shockwave pushing at his wings.

He reflexively pulled up, away from the fireball.

In that instant, the night became chaos.

Radio calls overlapped.

“Bogey breaking right!”

“He’s in front of me—break, break!”

“I’ve lost visual—where are you?”

Someone fired—they thought at a bomber, maybe at a shadow. Tracer fire crossed O’Hare’s nose, close enough that he flinched.

“Who the hell is shooting?” he shouted.

No answer.

Just more static, garbled words, a sense of confusion in three dimensions.

Then—

Silence.

Not on the radio, not in the Hellcat’s engine.

In O’Hare’s transmission.

His wingman tried to hail him.

“Skipper? Laredo One, this is Two. Say position. Say again. Anyone got eyes on the Skipper?”

No response.

The radar operator scanned his scope.

“Laredo One is faded,” he said. “No return.”

Search planes combed the area at dawn.

They found nothing.

No floating debris. No raft. No oil slick that could be confidently identified as a downed Hellcat.

The Pacific had taken Ed O’Hare the way it took so many—quietly, without witnesses, leaving only questions.

Friendly fire from a confused wingman?

A lucky burst from a bomber’s tail gunner in the instant after he fired?

Disorientation, a graveyard spiral in the dark, water looking like sky?

The Navy listed him as missing in action, presumed dead.

He was twenty-nine.

When the news reached the pilots who’d flown with him at Henderson and elsewhere, the reactions were as varied as the men.

One threw his helmet across the tent and swore.

Another sat down slowly and stared at nothing for a long time.

The lanky pilot who had once called the Hellcat a truck went out to the revetment where his own F6F sat and ran a hand along its wing in silence.

“Guess you knew what you were doing after all, boss,” he muttered.

The war did not stop for grief.

It never did.

Operations continued. Missions were flown. Japanese planes fell; American planes did, too.

But in the training syllabi that winter, new language began to appear.

About energy.

About vertical maneuvers.

About the Hellcat’s capabilities when flown, as one evaluation report phrased it, “to its full potential at high speeds.”

Ed O’Hare never saw those documents.

They saw him, though.

In every line that assumed a Hellcat pilot would think about more than just staying alive—that he might think about how to turn the fight in his favor.

By the time the war ground its way toward an end in 1945, the debates of 1943 about the Hellcat’s “slowness” felt almost quaint.

The numbers told a brutal story.

Hellcats had racked up more than five thousand aerial victories in the Pacific, more than any other Allied fighter. Against the Zero alone, the kill ratio hovered around thirteen to one.

It wasn’t just because the Hellcat was tough, though that certainly helped.

It wasn’t just because American industry could flood the ocean with carriers and aircraft while Japanese factories struggled under bombardment.

It was because the Navy had adapted.

Doctrine had shifted from simplistic “don’t dogfight” admonitions to more nuanced teachings about choosing where and when to engage. Pilots were taught to see fights in terms of energy states, not just angles. To use the vertical. To turn speed into altitude and altitude into surprise.

Instructors at places like Miramar and Oceana referenced reports from the Solomons and Central Pacific—after-action write-ups where pilots like O’Hare had dissected their own engagements, often in terse, technical language.

“Engaged six enemy fighters at approximately 10,000 feet, airspeed estimated 260 knots,” one such report might read. “Sustained high-speed turns and vertical reversals. Enemy appeared to lose maneuverability at higher speeds. Own aircraft maintained energy better than expected. Enemy broke off after losing four aircraft.”

Behind such dry sentences lay the vivid memories of men who’d flown with their hearts pounding, their hands sweating, their lives hanging on the difference between a high-speed controlled turn and a low-speed stall.

The Hellcat had not been designed as a dogfighting wunderkind in the same way the Zero had.

It had been designed as a weapon system—a platform that could bring significant firepower to bear, absorb damage, and be flown by both average and exceptional pilots.

Average pilots could fly it by the book, keeping it in safe envelopes, using numerical advantage, maintaining formation discipline.

Exceptional pilots could push its edges in ways the designers had maybe suspected but never fully explored.

Ed O’Hare belonged to the latter group.

He didn’t romanticize risk.

He simply understood that in war, the margin between survival and death for thousands might lie in the questions a few men had the nerve to ask.

Can this aircraft do more than we think?

Can this doctrine be bent in this circumstance?

What happens if we treat this limitation not as a wall, but as a boundary we can approach without crossing?

Years later, when pilots sat in jet cockpits staring at radar displays and HUD symbology, their instructors would still talk about energy, about vertical merges, about turning fights into opportunities to trade speed and altitude for position.

They didn’t always know they were echoing ideas first articulated in Hellcats over Rabaul and Wildcats over Coral Sea.

They didn’t always know the name Ed O’Hare, except as the guy whose name was on the airport they flew through on leave.

But the lineage was there.

A quiet pilot from St. Louis, who had earned a medal by doing the unthinkable and then spent the rest of his short life thinking very hard about why it had worked, had helped nudge fighter aviation from instinct and bravado toward something else.

A blend of instinct and analysis.

Of courage and calculation.

Of aggression and understanding.

Today, in Chicago, travelers hurry through terminals pulling rolling bags, checking phones, worrying about delays and gate changes.

They pass under signs that say O’Hare International Airport without giving much thought to the man behind the name.

In a quieter corner, away from the food courts and the polished duty-free shops, there’s a display.

A photograph of a young man in a flight suit, arms crossed, helmet tucked under one arm. Eyes steady, face serious but not grim.

A caption.

Edward “Butch” O’Hare.

Medal of Honor recipient.

Naval aviator.

Missing in action, 1943.

The display mentions Lexington, and the five bombers he shot down that day in 1942. It mentions his Medal of Honor. It might mention that he later led a night interception and never returned.

It probably doesn’t go into detail about the day over Rabaul when he dragged a “too slow” Hellcat into a turning fight with six Zeros and walked away with four more victories and a bomber still flying.

It almost certainly doesn’t mention stall speeds or energy retention curves.

That’s all right.

Airports are about destinations, not derivations.

But somewhere, in a filing cabinet in an archive, the original after-action reports are still there, yellowing, the ink fading but legible.

They’re written in a neat, precise hand.

Calm descriptions of airspeed and headings, of enemy positions and own-aircraft performance. Minimal adjectives. No melodrama.

The handwriting of a man who believed, deeply, that you owed it to everyone who came after you to write down what you’d learned, even if you’d had to learn it in the hardest way possible.

If you stand at the museum display long enough, if you look past the uniform and the medal and the posed photograph, you can almost hear, beneath the distant rumble of jet engines and the murmur of announcements, the hidden heartbeat of his story.

Not the legend of the lone hero.

Not the myth of the fearless ace.

The quieter, more dangerous idea.

That when everyone around you says, “That’s impossible; don’t even try,” it might be worth asking, at least once, “Under what conditions does that stop being true?”

The pilots who once mocked the Hellcat as too heavy, too slow, too forgiving to be a real fighter didn’t know they were mocking a question in progress.

O’Hare never set out to prove them wrong.

He set out to keep people alive and win a war.

In doing so, he gave the Navy something that outlasted him.

A fighter that turned out to be exactly as deadly as its numbers suggested it could be.

And more importantly, a mindset.

One that said:

Know your machine.

Know your enemy.

Know yourself.

Then, in the moment when doctrine runs out and chaos begins, trust the work you’ve done and the questions you’ve already answered.

On that day over Rabaul, six Zero pilots dove on a wounded bomber certain they knew exactly what the big blue fighter below them could and couldn’t do.

They were wrong.

Because one quiet man in that cockpit refused to let their assumptions write the ending of that story.

He wrote a different one.

Six came hunting.

Four didn’t go home.

And a “too slow” Hellcat, flown to the edges of its design by someone who cared enough to understand those edges, came roaring back to Guadalcanal, engine singing, guns empty, fuel low, very much alive.

The manuals would catch up later.

The myths would come later still.

But in that moment, with gun barrels smoking and the sky over Rabaul briefly cleared around a battered bomber, the lesson was simple.

Sometimes, the difference between mockery and respect is just one man, one aircraft, and one decision to turn where everyone else would have run.

News

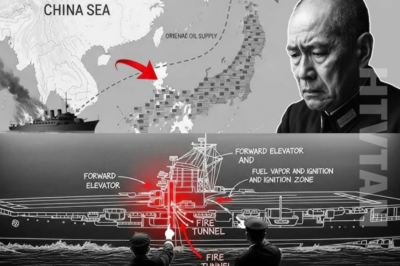

CH2. The Day Japan’s Oil Lifeline Died — And Its War Machine Collapsed Overnight

The Day Japan’s Oil Lifeline Died — And Its War Machine Collapsed Overnight The convoy moved like a wounded animal…

CH2. How One Girl’s “CRAZY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 TIMES Faster

How One Girl’s “CRAZY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 TIMES Faster Liverpool, England. January 1942. The wind off…

CH2. She decoded ENIGMA – How a 19-Year-Old Girl’s Missing Letter Killed 2,303 Italian Sailors

She decoded ENIGMA – How a 19-Year-Old Girl’s Missing Letter Killed 2,303 Italian Sailors The Mediterranean that night looked harmless….

CH2. Why Patton Alone Saw the Battle of the Bulge Coming

Why Patton Alone Saw the Battle of the Bulge Coming December 4th, 1944. Third Army Headquarters, Luxembourg. Rain whispered against…

CH2. They Mocked His P-51 “Suicide Dive” — Until He Shredded 12 Enemy Trucks in a Single Pass

They Mocked His P-51 “Suicide Dive” — Until He Shredded 12 Enemy Trucks in a Single Pass The Mustang dropped…

CH2. How 1 British Boarding Party Stole Germany’s Enigma Machine From a Sinking U Boat

How 1 British Boarding Party Stole Germany’s Enigma Machine From a Sinking U Boat The North Atlantic in May was…

End of content

No more pages to load