At 13, they ditched me, leaving me alone with nothing but rejection and cold silence. Years later, when I became an heiress, their sudden “love” reappeared, dripping with fake tears and greedy smiles. They thought I’d welcome them back, naive and broken. But I held a secret that would turn their shameless return into regret.

Part I — The Note on the Pillow, the Roses in the Moonlight

I was sitting at my desk staring at a bank statement that said I was worth millions when the doorbell rang and my past walked back into my life.

I’m Bella. I’m twenty-eight. And three weeks ago, I buried the one person who never left. My aunt—no, my mother—Margaret. She raised me from the day my parents vanished and, in death, left me everything she had built: a Craftsman on a tree-lined street in Seattle’s Capitol Hill, an eco-friendly home décor empire called Green Haven Designs, investments I didn’t yet have the vocabulary to describe. I was still raw from the funeral when my childhood knocked like it had a right to the front door.

Back then life had been a Polaroid. Grainy, warm. A small apartment with cracked sidewalks, a corner store that sold penny candy, Friday VHS nights with greasy pizza and the glow of a cheap lamp turning our faces into saints. My father, a car salesman with Sunday-morning smiles, always promised to bring home a sports car “someday.” My mother, a fourth-grade teacher with ink on her fingers and chamomile on her breath, graded papers at the kitchen table while I colored beside her. We burned pancakes on Christmas and laughed like that was the point.

I was thirteen when the film fogged over.

One chilly fall morning, the apartment was too quiet. Their closet was empty. On my pillow: Bella, we can’t do this anymore. Your Aunt Margaret will take care of you. We’re sorry. Sixteen words to end a childhood.

For three days I kept the note under my pillow and pretended it was temporary. The landlord banged on the door about rent I didn’t understand. The cereal ran out. The fear didn’t. It took a school counselor’s face—soft, braced—to pry the truth out of me and a social worker named Miss Harper with steady hands to make the call that would save my life.

Margaret arrived like the solution to a math problem. Tall, silver hair pinned to order, a navy coat that didn’t understand peeling paint. “Pack what matters,” she said, not unkind. I packed a duffel: a few clothes, a dog-eared copy of The Secret Garden, a photo of my parents and me in a county fair photo booth living a moment that turned out to be a costume.

Her house was a cathedral to wood and intention—stained glass that threw small rainbows on the entryway tile, rugs that remembered careful feet. From the bedroom window I could see a sliver of Puget Sound glinting like it had overheard my story and chosen not to comment. On the first night she set rules the way generals draw maps: breakfast at seven, no shoes indoors, homework at desks, not beds, piano on Tuesdays and Thursdays, honesty always. I tested every line like a child who had learned that love means surviving tests. I left dishes in the sink; the kitchen closed until the next meal. I skipped piano; she drove me to the lesson and sat in the hallway knitting forty minutes of accountability. I failed a history quiz; a tutor appeared like consequence dressed as kindness.

It took weeks to understand that discipline was her word for devotion.

One night I found her clipping roses in the moonlight, pale blooms glowing like a small apology from the world. “You’re tougher than you think, Bella,” she said, handing me a bloom. I believed her because she said it like an observation, not a pep talk.

She enrolled me at Hillrest Academy, where teenagers parked cars I had seen only on posters and wore their fathers’ portfolios like cologne. I arrived with a thrift-store backpack and a permanent sense of trespassing. The first time I stumbled in calculus, I stayed up past midnight with the textbook like a weapon, the desk lamp a small sun. “You’re not here to blend in,” Margaret told me. “You’re here to stand out.” It sounded like pressure until it started to sound like permission.

I found a rhythm. My name rose into honor roll lists. A scholarship letter came with a seal that felt like a handshake I wanted to keep. I majored in business at the University of Washington because Margaret said options were a better bet than wishes, but I smuggled art into my life through a design minor and Sunday afternoons in museums where color explained things I couldn’t.

Summers, I worked at Green Haven. I learned the way bamboo bends without breaking, the politics of vendors who preferred to be courted, the vocabulary of supply chains and margins and how to make recycled glass look like desire on a shelf. Margaret let me build window displays and then entire campaigns. We stopped arguing about whether creativity had a place in business because the numbers voted with my side.

Then cancer arrived without making an appointment.

“Pancreatic,” the doctor said to a woman who had rarely met something she couldn’t outwork. Margaret fought with stubborn elegance, spreadsheets of treatment options, lipstick on onco-clinic days. I ironed fear into small squares and placed them in drawers labeled meals and meds and insurance and be here. One night when her hands shook too much to sign, I read her contracts aloud until the words settled. Another night as I tucked a blanket under her feet the way she always loved, she gripped my wrist. “You’re my legacy,” she said. “Don’t let anyone take that from you.”

When she died, the house grew an echo. Even the floorboards were careful. The roses continued to bloom, because plants do not negotiate with grief.

Three weeks after the funeral, Charles—her lawyer with a tie collection and a humor so dry you could stack books on it—called me to his office for the will reading. I expected teak furniture, tea, maybe a few managers from Green Haven who had kept the lights on while I remembered how to breathe. I did not expect my parents in chairs opposite mine like a bad magic trick.

My father was larger, jaw gone soft, hair surrendered to gray. My mother’s face had angles I didn’t remember. Her smile was too bright, as if it had been rehearsed for years without ever being needed.

“Bella,” my father said, warmth like a borrowed jacket. “You’ve grown into quite a woman.”

My mother reached for me the way someone reaches for a child in a grocery line that belongs to someone else. “We’re your family,” she said, and the perfume of old chamomile turned sour.

Charles walked in and their expressions slipped. He sat, opened a leather folder that made a soft sound like truth stretching, and read.

The house. The business. The portfolio that made my bank app feel like a novel with a twist. Everything to me.

My mother’s hand found mine like a spider. “This is a lot for someone your age. As your parents, we can guide you.”

My father’s voice went casual in a way that announces calculation. “Legally speaking, we’re still your guardians. Your aunt only had temporary custody.”

Before my mouth could find a shape for protest, Charles cleared his throat the way men clear stone from the path. “There’s a misunderstanding,” he said mildly. “Margaret adopted Bella at sixteen. She’s been her legal daughter for more than a decade.”

He slid papers across the desk. Birth certificate amended. Court orders. My name attached to hers in ink that had outlived a judge.

Margaret, a woman who loved precision, had quietly made me hers and never told me because she trusted love more than law.

My father’s face lost a layer of performance. “We never agreed to that,” he said. “Those papers are fake.”

Charles didn’t dignify that with rhetoric. He opened another file. “Margaret asked me to prepare for this.” Photos. Reports. A recording played through his phone’s small speaker: my father’s voice on a payphone, six months after they left me, in Reno—a city that advertises miracles at 3 a.m.—asking a man named Martin Walsh how to “get that paperwork done.” Charles slid a signed termination of parental rights across the desk, dated, notarized, recorded.

My mother made a sound that was half-sob, half-self-pity. My father’s jaw clenched like a handful of broken teeth.

Charles handed me an envelope with Margaret’s handwriting on it. I opened it the way you unwrap a fragile ornament you’ve been told is not replaceable.

My dearest Bella, it began. If you are reading this, your parents have come for your inheritance. They tried to extort me years ago—$150,000 not to fight for you, more later for their debts. I refused, of course, and they signed you away. I adopted you without telling you because I wanted you to know love without paperwork. I hope you never have to read this. But if you do, know that I anticipated their return and I have built walls they cannot breach without destroying their claim entirely.

She had built a fortress and called it a garden.

My father pointed across the desk at me like the world had appointed him judge. “You’ve been brainwashed,” he said, but even his voice sounded bored with the narrative.

I stood, letter in hand, and found a steadiness I hadn’t known had been waiting. “Margaret was my mother,” I said. “She showed up when you didn’t. You don’t get to walk back in now because the bank app got interesting.”

Charles folded his hands. “Any attempt to challenge the will triggers a clause Margaret insisted on. Everything goes to the Margaret Hughes Foundation for Abandoned Children. You’d get nothing.”

Their attorney—Victor, who had the expression of a man accustomed to losing prettily—leaned in and whispered. My father stood so quickly the chair leg squeaked across the hardwood. He stormed out. My mother followed, her eyes glancing not at me but at the folder on the desk.

That night they came to the house anyway, because people who have not lived with boundaries think locks are suggestions. I buzzed them in, not from hope but for closure.

“We were sick,” my father said, choosing words in a way that suggested new therapy. “Depression, addiction. We thought Margaret would—”

“You knew where I was for fifteen years,” I said. “You called social services to check I was alive. You never called me. You mailed no card. You left a note on a pillow and let a child be a problem someone else solved. Now you are here because there is a number in an account.”

My mother looked up the staircase the way a tourist looks at architecture. “We can fix this,” she said. “We can be a family again.”

“There’s a camera in the corner,” I said, pointing without looking. “Margaret recorded every call, every demand. She protected me from your stories. Leave, or the police will make you.”

Their last words were a blessing in disguise.

“You’ll regret this, Bella,” my mother said, throwing my name like a plate.

I closed the door softly enough to prove that I didn’t.

Part II — The Adopted Daughter, the Prepared Mother

Grief moves into a house and rearranges the furniture. It leaves a spoon on a counter and you cry. It brings you a letter and you learn something you didn’t know you needed, like the fact of your own adoption; you cry again, differently.

I found the adoption decree in a drawer labeled IMPORTANT in Margaret’s block printing. A photocopy of a girl in a juvenile courtroom with a silver-haired woman holding her hand. Me. Her. A judge who didn’t smile because the truth didn’t need decoration. The papers were accompanied by receipts—tuition, braces, a piano ledger. Love quantified, but not itemized; she would have done it for free, and in the ways that mattered, she did.

In the same drawer, beneath a rubber-banded bundle of life insurance documents, a box: my Hillrest report cards, a photo from graduation with Margaret’s arm around me so tightly you can’t tell where my fear ends and her confidence starts, a Polaroid of me at nine with paint on my cheeks and a pancake burned in the middle, all contained by a note: Bella, I love you not because I had to, but because you are you.

I slept with that note on my nightstand for a week, touching it in the dark the way people touch a Saint Christopher medallion before driving. I filed for a restraining order, gave the security team file numbers and faces, and then did something that felt both small and monumental: I opened all the windows.

Light changed the house’s shadows. Linen replaced heavy curtains. The library stayed her library; the garden stayed her domain—roses like small moons, espaliered pear trees, a bench that remembered the insomnia nights we’d sat there while she pretended the tea was for warmth and not for company.

Green Haven thrummed with the tension of grief and revenue forecasts. I met with the executive team, the store managers who had learned Margaret’s tempo and mine. “We keep what she built,” I told them. “We adapt where she resisted. We don’t grow for growth’s sake; we grow for meaning.”

We launched an online store she had always thought was “too impersonal.” We designed a line of recycled wool throws in colors named after the Puget Sound at different weathers. We opened a Portland location where the window display made people stop and press their palms to glass like something inside was a memory they couldn’t place. Sales climbed. Staff told me Margaret would have liked the quinoa salad we’d introduced in the café and laughed at me for the herb names on the chalkboard. I learned how to run a P&L by heart and a team by listening.

But the most important spreadsheet lived in a different folder: The Margaret Hughes Foundation. She had started it in theory; I made it live. A nonprofit for kids like me who had experienced the sentence on my pillow. Legal aid. Therapy stipends. Mentors we vetted like surgeons. Weekly dinners with real plates. A room with a lock that only they controlled. The first time a girl named Tasha scraped her fork across the plate and told me she wanted to study architecture “because buildings don’t leave,” I excused myself and cried in a supply closet.

Mrs. Aurora—Margaret’s housekeeper with a heart that could shame churches—stayed. We sat at the kitchen island with coffee cups that had been set across these counters for twenty years and she told me stories Margaret had never told me. How, when the first store was failing, she learned accounting from YouTube and librarians. How she once spent an entire night stitching new pillow covers because the vendor’s shipment had arrived stained and she refused to display anything she wouldn’t put on our couch. How she had been terrified before I arrived but read three parenting books in two days and then decided to trust her instincts over expert’s chapters.

Charles started coming to Sunday dinners. He brought over wine and cautions, an amateur’s affection for sourdough, and grief that loved me by being honest. He told me Margaret had once called him at 3 a.m. convinced she had ruined my life by insisting on algebra instead of cologne-scented boyfriends. He told me he’d said, “You raised a woman who reads contracts. That will save her more often than algebra will.”

I started therapy with Dr. Ellis, who looked like the aunt who always knows where the scissors are and tells you to cut the tag off instead of living with the itch. “You don’t need their apology to move on,” she said. “You need your permission.” We practiced saying no to ghosts.

My parents tried one more theater. They sent a letter to a local paper implying Margaret had “coerced” me. The editor—who had known Margaret since her first pop-up shop—emailed back only the words How dare you and forwarded the message to me, asking if I wanted to pursue anything. I filed it in a folder labeled Noise. It turns out you can choose your own soundtrack.

A letter arrived from my mother months later. No demands on the outside. Just my name in handwriting I could recognize even if I’d been asleep for a decade. I put it in my desk drawer unopened. It wasn’t cruel. It was careful. When Dr. Ellis asked what I imagined it said, I told her I hoped it said I’m sorry and I couldn’t and I know you’re better without me. When she asked why I hadn’t opened it, I said because mercy is sometimes marveling at how much you don’t need.

On a Saturday, I visited Margaret’s grave in a cemetery with old trees that know how to listen. I laid dahlias on the stone that said MOTHER because that’s what she was, regardless of paperwork. I described the Portland store, the online launch, the way Tasha had drawn a house that looked like a sanctuary and a ship. “You showed me what family means,” I said. “It’s who stays. It’s who shows up.”

A wind lifted the leaves. It felt like approval. Or physics. Sometimes the difference is mercy.

Part III — Their Return, My Secret

They thought I was an easy mark. I didn’t blame them. They’d last seen me as a kid clutching a note like a lifeline can be made of paper. They did not know about Margaret’s habit of preparing for storms while the sky was still blue.

They did not know about the recordings.

Margaret had asked Charles to set up a clean security protocol years ago—not out of paranoia, but prudence. “People return when the harvest looks good,” she’d said, and the sentence had felt both biblical and like a spreadsheet.

Hidden in the paneled wall of the entryway was a safe the color of discretion. It held documents I had already seen—the adoption decree, the termination, copies of the will—but also a small black drive. Charles brought it to me with a flourish that would have pleased Margaret. “You’ll know if you need it,” he said.

The drive contained more than phone logs. It had recordings. My father on calls to a man named Walsh—Martin, with an accent that made words feel like loose screws—complaining about “the old bat” and demanding more for “the kid.” It had my mother’s voice on voicemails: We’re family. You owe us for taking her. It had a particularly vile conversation between my father and a girlfriend I didn’t know about until that moment, where he laughed at the idea I remembered Christmas pancakes.

It also had bank transfer records. Fifteen thousand dollars went to my parents when they terminated their rights. A later deposit—twenty thousand—landed in my mother’s account around the time the landlord had banged on our apartment door; I had still been there, living off cereal dust. She had not paid the rent. She had used it to buy a used Lexus. Charles didn’t narrate that detail. He let the numbers narrate themselves.

I did not blast any of this onto the internet. The Margaret Hughes Foundation didn’t need to be contaminated with spectacle. But when their threats shifted from whine to howl—“We’re calling the papers; we’re coming to the house; we’re going to court”—I invited them to coffee. Not in my house. In a neutral café with a camera in the corner and Charles at a table nearby reading The Economist like a man in a spy novel.

My father wore an apology like a jacket he hadn’t tailored. “We made mistakes,” he said, eyes on the bag at my feet. My mother cried without tears. “I’m sick,” she said, as if diagnosis were a confession that automatically absolves.

“Here’s my secret,” I said, and slid a printout across the table. Their termination of parental rights. Their signatures. The fifteen thousand dollar transfer receipt. Margaret’s note to Charles and the transcript of a voicemail they’d left three years later asking for “another twenty because the girl doesn’t need braces that bad.”

My mother stopped producing sounds. My father’s jaw worked like a mechanism. “We were desperate,” he said.

“You were cruel,” I said, still polite because Margaret would have wanted that. “And then you were absent. And now you’re opportunists.”

He leaned forward. “This is blood,” he said, tapping the table between us. “You can’t change blood.”

“Margaret did,” I said. “She changed what counted as family. And then she made it legal.”

“Your aunt—”

“My mother,” I corrected.

He stood so fast the chair scraped. People looked up. “You’ll regret this,” he said again, as if repetition creates fact.

“I used to regret you,” I said. “I don’t anymore.”

They left righteous and failed. Maybe those two things always travel together.

I walked to the counter, tipped too much, and thanked the barista for not filming what could have been a viral moment. Then I met Charles at the table by the window. He slid me a folder.

“A backstop,” he said. “If they try anything else.”

Inside: a pre-filed restraining order with an affidavit from a security expert; the letter from the paper’s editor vowing not to run their smear; a letter Margaret had written to be sent to me if I ever doubted her. You are not an accident I had to explain away, it said. You are my proof that we get to choose love and tell the truth with our choices.

I went home and stood in the garden and practiced breathing without measuring.

Part IV — The End They Didn’t See Coming

Green Haven’s holiday season arrived like a wave and washed over everything except the rooms grief refuses to decorate. The Portland store hit its numbers. The online shop’s recycled glass ornaments sold out in three days; we posted a video of artisans making them and people cried in the comments because transparency is the new luxury. The Foundation held a winter dinner. We ate lasagna and garlic bread on plates, not Styrofoam, and Tasha showed me a sketch of a building that made my chest hurt.

In January, I took two weeks and did nothing spectacular. I learned how to make omelets Margaret would not have approved because I used too much butter. I biked along a shoreline that remembers storms and forgives them. I read paperbacks in baths. I slept. When insomnia pressed its cold fingers against my sternum at 3 a.m., I let it. And then it passed.

In March, a thin envelope arrived from Reno. The return address was a strip-mall law office. Inside: a stamped copy of a bankruptcy petition with names I used to write across Father’s Day cards. It was not triumph. It was a diagram of consequences that finally found the right house. I mailed a check to an addiction treatment center in their city with a note in Margaret’s tidy style (I wrote it, but I used her kindness): For someone’s second chance. I did not sign my name.

In April, the garden bloomed so extravagantly it felt like a rebuke to restraint. I cut armfuls of roses and filled the house with them, not because I needed to prove anything but because Margaret would have. In May, we launched a line of reading lamps inspired by the one that had lived on our kitchen table at the apartment I was supposed to forget. I named the color “Chamomile,” and it made me laugh. Healing can be petty. Still, it heals.

In June, I stood in the mirror and saw a woman who looked like she could read a spreadsheet and a poem in the same afternoon. The bank statement still said a number that made me careful; the Foundation’s statement said a number that made me proud. The house looked like mine. The business sounded like me. The girl who waited for a door to open that would never open had finally learned how to bless a closed one.

I went to visit Margaret. The cemetery was green and kind. I pressed my palm against MOTHER and told her what I had done.

“I kept the secret,” I said. “And then I used it to tell the truth.”

It turned out the secret wasn’t the adoption papers or the recordings or the clause in the will that would have sent everything to the Foundation if my parents had dragged me to court. The secret was simpler and so much harder: I finally understood I did not owe an audience to the people who left me.

I owed love to the people who stayed.

On the walk back to the car, my phone buzzed with a number I didn’t recognize. I let it go to voicemail. At home, I played it on speaker while arranging roses in the kitchen. My mother’s voice emerged—older, softer.

“Bella,” she said. “This is not about money. We are… we are not well. I wanted to say—” She stopped. A breath. “I wanted to say that whatever you decide, I hope you are happy.” The click at the end felt like a bow.

I didn’t call back. Not because I’m angry. Because I’m careful. I put the voicemail in the folder labeled Noise, then moved it to a new one called Mercy. Maybe one day I’ll open her letter. Maybe I won’t.

At the Foundation’s summer picnic, Tasha stood at a microphone we’d rented for the band and said, voice wobbling, “Thank you for not being a form I filled out once.” The kids cheered. The staff clapped. The younger kids ran through sprinklers and yelled like their bodies could hold all that sound.

I looked around and realized this was the inheritance that mattered most. The house, the business, the zeros on screens—they were all scaffolding. The actual building was this: a life not defined by who left me at thirteen but by who taught me what to do after.

On the way home I stopped at the corner where a shop used to sell penny candy in little paper bags. It’s a smoothie place now, all glass and optimism. I stood there a minute and let both maps lay over each other: the old one filled with hunger and waiting, the new one full of choice.

They thought I’d be naive and broken and grateful for their sudden love. They thought I’d be a bridge back to a life they’d gambled away. They thought I’d be too stunned by money to remember what absence feels like.

They didn’t know I was an adopted daughter with a mother who prepared me for storms.

They didn’t know I had a clause that would send the entire estate to children like me if they stepped out of line.

They didn’t know the secret Margaret taught me that I now teach to anyone who comes through the Foundation doors: You owe love to the people who stay. You owe nothing to the people who leave and return with open hands.

So when the doorbell rang and my past tried to come in, I opened the door, listened, and then closed it with care. And the life on the other side kept growing—like roses in moonlight, stubborn and soft, exactly the way my mother would have wanted.

The End.

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. I sat in my son’s ice room after his car accident. The surgeon said, “His chances of recovery are minimal.”

I sat in my son’s ICU room after his car accident. The surgeon said, “His chances of recovery are minimal.”…

CH2. My Family Broke In With Baseball Bats When I Refused To Sell My House And Pay Their $150K Debt…

When my parents cut me off for five years because I refused to sacrifice my $120,000 life savings for my…

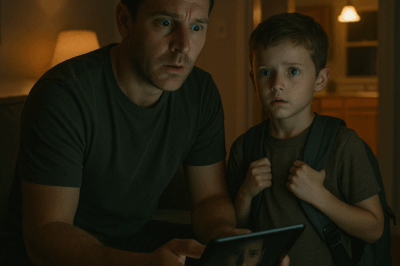

CH2. My 7-year-old son came home with his tablet hidden in his backpack. “Dad, my teacher doesn’t know I recorded this. You need to hear it.”

My 7-Year-Old Brought Me a Recording of His Mother — I Packed, I Listened, and Then I Ended the Story…

CH2. My Parents Assaulted Me As My Daughter Watched — I Let Them Stay Before Destroying Their Lives…

My Parents Assaulted Me As My Daughter Watched — I Let Them Stay Before Destroying Their Lives… Part I —…

CH2. “Probably here begging for a job” my brother-in-law joked to his coworkers. “That’s my wife’s unemployed sister.

“Probably here begging for a job” my brother-in-law joked to his coworkers. “That’s my wife’s unemployed sister.” They all laughed…

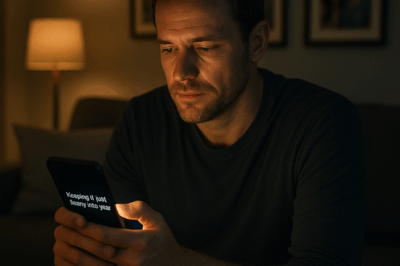

CH2. “Keeping it just family this year,” Dad texted in the group chat.

“Keeping it just family this year,” Dad texted in the group chat. Hours later, they posted photos — all smiles…

End of content

No more pages to load