“There’s No Place For You Here!” My Daughter-In-Law Said On Christmas, So I Left. The Next Day…

Part I — Christmas at the Door

Snow fell the way memories do—soft at first, then heavy enough to bend even the strongest branches. I walked slowly, careful on the icy pavement, a small paper bag tight to my chest. It crackled each time I hugged it closer, as if the cookies inside wanted to whisper, “Be brave.” A knitted scarf peeped from the top—wine red, stitches a touch uneven where my fingers had trembled with arthritis—and a doll with soft yarn hair stared up at me from tissue paper, patient as only dolls can be. Lily would love her. She always loved my stories more than the ones on TV.

The house glowed from the lane. Warm. Golden. Laughter pulsed through the windows like a heartbeat. For a moment my feet didn’t move. I just watched, and I thought of Daniel at five, his nose pressed to this same glass, palms fogging up circles while snow came down in thick lace. His father—Mark—behind him, pointing out constellations as if stars were part of the family too. Mark used to say love is a house you build, brick by steady brick, and then you keep it warm. When he died, I promised to do that alone if I had to.

I rang the bell. Somewhere, a choir on a TV sang a descant I hadn’t heard in years. I smiled and tucked a loose strand of hair behind my ear.

Clara opened the door.

She was beautiful in a glossy sort of way, the red and gold of her dress catching the light, a necklace at her throat that looked like frost if frost could cost rent. Her cheekbones were sharp enough to slice a ribbon. Only her eyes were wrong—cool, flat, like unbroken ice on a lake you shouldn’t trust.

“Oh,” she said, lips curving without warmth. “It’s you.”

“Yes, dear,” I answered. “Merry Christmas. I brought—”

“You should have called,” she said, not unkind in tone but perfectly precise in intent. The way you tell a delivery you didn’t order to try next door.

“I wanted it to be a surprise.” I tried to sound light, the way I used to when I told Daniel elves were real. “I made cookies. And a doll for Lily. And—”

“We already have guests,” she said. She didn’t turn to look. She didn’t need to. “There’s no place for you here tonight.”

The words slid off her tongue like they’d been rehearsed. Maybe they had been. Families practice more than carols at this time of year.

I peered past her shoulder. Daniel was by the fireplace, kneeling, helping Lily untie a bright ribbon. His profile hasn’t changed since ten—still boy enough to make my chest fold in on itself. “Daniel,” I tried, just his name, soft as I could make it.

His head lifted. Our eyes met. Something flinched in his. Then he looked away as if someone had said his name in another room.

“Please,” Clara said, lower now, almost intimate. “You’re making things awkward. We’re in the middle of dinner.”

It was like watching a door close from far away—the click more imagined than heard, final anyway. I tucked the bag tighter against me. My fingers had gone cold around the paper.

“I see,” I whispered. “I understand. Merry Christmas.” I smiled because I have always believed in the dignity of small goodbyes. Then I turned and walked into the kind of night that makes you count your breaths. Snow stung my skin in hot needles. I didn’t wipe the tears. Let them freeze. It was cleaner that way.

At the end of the street I looked back. Through the window: warmth, faces bright as polished apples, glasses raised, plates passed, life contained and curated. When Lily turned and caught sight of me in the dark—for one instant—I thought she might call out. But someone laughed, and someone lifted a toy, and the moment folded shut like a book you were about to open.

“There’s no place for you here,” I repeated under my breath, and the words condensed in the cold into something I could see and name.

My apartment was as small as I remembered when grief moved in, and just as faithful. The heater rattled like an old soldier and tried its best. I put the bag of gifts on the table and touched the photo of Daniel at seven, chocolate frosting in his eyelashes from a cake we’d made together when I forgot eggs and replaced them with applesauce. He’d laughed like joy is a muscle. “You used to wait for me by the window,” I told the glass. “You’d jump before I could even get my boots off.”

Outside, the city hiccupped firework confetti into the night. Inside, I curled into the old chair Mark used to call the boat because it rocked the way waves do when you want to be held. TV families hugged each other while snow machines worked hard in the corners of sets. I turned it off.

The phone buzzed, a small bee against a quiet table. Unknown number. A message: Reminder—Mr. Harris, estate attorney. Appointment tomorrow 10:00 a.m. to finalize property management transfer. Please confirm.

Mark’s attorney. I’d made and cancelled that appointment three times. His papers still smelled like cedar from the box he kept in his closet. I had been afraid to open them because grief is a magician; it makes rabbits of bills, debts of photographs, light of stone. But the word “finalize” tugged at me now. Maybe it was the way Clara’s voice had felt like an eraser. Maybe it was Mark’s hand in the memory of mine, steady even when everything else shook.

I typed back: Confirmed.

I made tea that tasted like memory and sat by the window while the candle sank into itself. If this was an ending, perhaps it was the right one. If it was a beginning, perhaps it was kinder than I expected. Somewhere between those two ideas, sleep came, slow as winter light.

Part II — The Paper That Remembered Me

Morning lifted slowly, a heavy blanket dragged along by an uninterested day. I wrapped the scarf I’d meant for Clara around my neck—it looked kinder on me—and walked to the tram. The city limped in the cold, determined. People carried packages and bread like both weighed the same. It made me love them more or less, I couldn’t tell.

Mr. Harris’s office seemed out of time. Brass handles that had been polished more by years than by hands. Plants that refused to die in corners that refused to brighten. He stood when he saw me, kindness moving across his face like a decision. “Mrs. Evans,” he said. “You made it.”

“I almost didn’t,” I confessed. “But something told me…”

“Come,” he said, and the word was warm enough to melt a bit of the ice I’d packed around myself. He had my file already open. Paper slid under his fingers in purposeful stacks. “Your husband was a thorough man,” he said, admiration in the flat tone of lawyers when they are careful with praise. “He left clear instructions. Until your passing, all properties remain in your name.”

I blinked. “All?”

He nodded, reading. “Primary residence on Maple Street… two rentals in need of roof repairs he has notes about that—remarkable—” he murmured, and then: “And as for Maple Street, he writes: ‘Our home belongs to my wife until she no longer wishes to be its keeper.’”

“My home,” I repeated. The room shifted under me, a slow vertigo. “The house my son lives in.”

“Legally?” Mr. Harris tilted his head. “Your guest lives there.”

Clara’s words—the door, the golden light, her shoulders filling the frame—shocked through me again, and then something unbelievably quiet loosened. “I didn’t know,” I said, hearing the surprise in my own voice.

“It is all here,” he said, sliding the crisp documents closer, your name, the boundaries of what belonged to you, and until yesterday, what you were willing to give away.

He watched me read with polite patience, seeing, I think, the kind of tremble that has nothing to do with cold. The signatures were a map back to a home I had thought forever lost not by death but by shame. I signed where he pointed. The pen felt heavier than it ought to. It drew a line where I drew breath. When I put it down, something inside me stood up.

“It’s done,” he said. “You have full authority over Maple Street. What would you like to do?”

The window held a view of a city refusing to be crushed by weather. People moved under it with their heads down and their hearts up. I borrowed some of their posture.

“For now?” I said. “Nothing. Sometimes the best way to teach people a lesson is to let them think they’ve learned it already.”

He smiled, not to approve but to acknowledge a choice. “Call if you need anything,” he said.

I stepped out into the light a different woman than the one who had gone in. Not younger. Not richer. Just steadier, like a table that had finally had its wobble fixed with a folded piece of paper under one leg.

Part III — The Knock on Maple Street

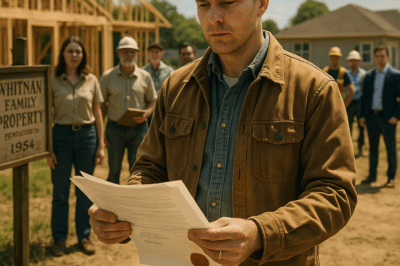

It snowed overnight a few soft inches: a second chance for everything that needed covering. I dressed in the coat Mark had always said made me look like a general who’d won her war and forgot to mention it. I put the scarf around my neck again and stepped back into the kind of winter that clarifies.

The house looked like a Christmas card still. Wreath bright on the door. Lights insisting on delight along the roof. Laughter like silver—a sound Lily must have learned from her father because I always forgot how to laugh that way in December.

I rang the bell.

Clara opened the door, face painted on in meticulous lines, the color in her cheeks exactly one wrong shade—a mistake only pride makes. “You again,” she said. No preamble, no mercy. “Didn’t I make myself clear on Christmas?”

“You did,” I said, smiling because I like to be underestimated. “But it seems you were mistaken.” I held out the folder Mr. Harris had assembled, paper that felt like it could tip scales in the right hands. “You might want to read this before your mouth finishes that sentence.”

Confusion flickered, then irritation, then something like a shadow of fear. She didn’t step back to let me in. She stood there and turned the pages in the doorway like the answer might be to hold the law in the cold until it went away.

Color leaked from her face. “This says the house…” She stopped, mouth open in a shape I hadn’t seen on her before—absence. “Belongs to you.”

“It always has,” I said. “As long as I wanted it. Your invitation was… generous. But unnecessary.”

Daniel appeared in the hallway like a child who’d been caught where he shouldn’t be. “Mom?” His voice broke on the single word in a way that turned me back and forward through time without mercy.

“Ask your wife,” I said gently. “She’s good with statements.”

Clara swallowed. “We thought—”

“You thought it would be easier to say no to a person than to a document.” I didn’t raise my voice. I haven’t in years. “You told me there was no place for me here. That is correct. Not for me. Not anymore. But not for cruelty either.”

Daniel looked from the papers to me, as if choosing love were a mechanic: red wire or blue. “I didn’t know,” he said, and the truth or the lie didn’t matter then. It had been easier not to know. That’s the sin most people can live with.

“I’m sorry,” I said, and I was—for the boy he had been and the man who had been taught to step back from his mother. “You have two weeks to make a plan. I’m selling the house. It deserves to be filled with something kinder than what you put in it.”

Clara’s mouth worked, and in it I saw all the edits she wanted to make to my sentence, all the old drafts of herself she still preferred. “You can’t—”

“I can,” I said. “I signed a thing that lets me, and your mouth doesn’t make the ink disappear.”

Daniel reached for my hand. He still had the same warm palms he did as a boy, the scar from the time he touched the kettle and learned the lesson it really does teach. “Mom, please,” he said. “We can fix this. She didn’t—”

“Daniel,” I said, squeezing once the way I used to when he was too close to tears. “I forgave you when I walked away in the snow. I still will. But forgiveness and consequence are not opposites. They keep each other honest.”

The house behind them hummed quietly: radiators, the small whir of a heat vent, the earthquake stillness of a room waiting for a decision. Lily’s laugh spilled from the living room and hit me square in the throat. Love always hurts exactly where it counted most.

“Take care of Lily,” I said, and I felt myself say it to more than the man in front of me. I said it to the space that any child makes in a house. “She deserves a home that knows how to be kind. So do you. Find one.”

I turned. The light on the snow caught in a way that made it look like the world was applauding and pretending not to. My boots sunk clean. My heart made a sound I didn’t recognize. It might have been ease.

Part IV — The Place With My Name On It

Escrows are slow and fiddly and perfectly designed to test patience. I signed papers with steady hands. The realtor—who had sold this house to me and Mark with a baby in one hand and a box of mugs in the other—hugged me in a way that said people do their best when the world lets them. A young couple with a six-month-old named Eva bought the house and cried into their closing folder. I gave them the recipe for the ginger cookies that I always baked when the first frost hit and told them the kitchen windows like to be opened in March even when the air is sharp. I gave them the tree schedule: apple in April, maple in October, and don’t let anyone cut the lilac bush—not for any money.

Daniel moved. He took the armoire that had been his grandmother’s after asking if he could, and he left the squeaky rocking horse that had been his and Lily’s and mine to move and then not move as needed. Clara kept the wreath until it dried into brittle leaves and then she forgot to throw it away. She texted me on a Sunday three months later to ask if I wanted it. I texted back, “You can let it go.” She did, I think.

I used proceeds to buy myself a small place with sunlight, the kind that pools on rugs as if it chose you. I painted two walls and hired a woman named Sana to paint the rest because my wrists complained and I’ve learned to listen when the body sends emails instead of letters. I put Mark’s chair by the window. I put Lily’s doll on a shelf where she can always see it when she visits. I hang photos of Daniel at five, at fifteen, at twenty-five. Not to punish myself; to remind myself that love has phases and sometimes this is the phase where you let it be smaller and truer.

On Easter, Lily spent the weekend with me. We baked the cookies I hadn’t given away. She asked if Santa lives here during the summer. I told her Santa is busy and that grandmothers are year-round. She laughed and bit the ear off a rabbit cookie while looking me in the eyes like she knew exactly what goodness costs.

A letter arrived from Clara on expensive cream paper with my name spelled too formally. It smelled like a department store. “We didn’t mean it to go so far,” she wrote, as if meanings are maps and not excuses. “Don’t destroy family over pride.” I put the letter under the plant on the sill and watered it. The plant did well. The letter did not.

I started teaching one afternoon a week at the community center: “Navigating Estates and Kindness Navigation: How to Keep Your Papers While Keeping Your Peace.” People brought stories like bruises. We compared notes on what signatures mean and do not mean. We made half a dozen new friends over a pot of weak coffee and a plate of cookies that taste better when you talk.

Two years later, Clara and Daniel sat on the other side of a round café table from me. It was spring, wet and insistent, the kind of green that forgives everything. They looked older in the ways that matter and in the ways that don’t. Daniel apologized without tears. Clara apologized without pride. I said yes without forgetting. We set new rules on a napkin and later with Mr. Harris: holidays will be scheduled with generosity; Lily will not be used as a gift you can give or take; no one will ever be turned away without a coat.

At Christmas now, I arrive when I’m asked, and they come when invited, and we keep a folding table in the hall for the years we accidentally love more people than the house expects.

The scarf I knitted for Clara rests on a hook by her door. She wears it. Maybe because it is warm. Maybe because it is a piece of wool that remembers what we forgot.

This is how the story ends: not with shouting, not with slammed doors. With a woman standing in winter learning that she still owns the keys to her life. With paper that remembers her name and hands that write it. With a house sold, a home found, a family that is smaller and kinder and therefore real.

There is no place for me in a house that speaks cruelty. There is place everywhere else. And on snowlit nights, when lights flicker and I walk carefully because life taught me both the joy and the danger of ice, I hold a paper bag of cookies and a doll with yarn hair and a scarf that fits my own neck best. I ring a bell I am welcome to ring and am welcomed in.

Sometimes justice is a document. Sometimes it is a door left open. The trick is knowing which one to knock on and when to walk away.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. My Niece Texted Me, “You’re Not Welcome At My Graduation. Stay Home, Loser.”

My Niece Texted Me, “You’re Not Welcome At My Graduation. Stay Home, Loser.” My Sister Added A Thumbs-Up Emoji. I…

CH2. My Wife Mocked Me in Front of Her Boss — I Left the Party, and That’s When Her Life Fell Apart

My Wife Mocked Me in Front of Her Boss — I Left the Party, and That’s When Her Life Fell…

CH2. My Family Said:”You’ll Firgue It Out” After Moving Away Without Me At 17—When I Made It, They Tried…

At seventeen I was abandoned by my family. I came home to an empty house and found only a note…

CH2. At Thanksgiving Dinner, My Sister’s Kid Threw His Fork at Me and Said, “Mom Says You’re the Help…

At thanksgiving dinner, my sister’s kid threw his fork at me and said, “Mom says you’re the help.” The table…

CH2. While I Was Lying In The ICU My Brother Said “I Sold Your Apartment In The Center Of Moscow For $65k

When I was fighting for my life in the ICU, my own brother made a shocking confession — he sold…

CH2. HOA Built on Our Land Without Permission—They Panicked and Ran When We Came Back Armed!

HOA Built on Our Land Without Permission—They Panicked and Ran When We Came Back Armed! Part I — The…

End of content

No more pages to load