The “Texas Farmer” Who Destroyed 258 German Tanks in 81 Days — All With the Same 4-Man Crew

The morning sun of July 16th, 1944, rose over the blood-soaked fields of Normandy like a tired witness, casting long shadows across a landscape that felt less like France and more like a graveyard built for all mankind.

In the turret of an M4 Sherman tank called In the Mood, a soft-spoken man from Farmersville, Texas, pressed his face to the gun sight and exhaled slowly.

Staff Sergeant Lafayette Green Pool—“War Daddy” to the men who followed him—studied three German Panther tanks positioned along a hedgerow eight hundred yards away.

Three Panthers. Each one a steel predator built to kill him.

Inside the cramped turret, the air smelled of oil, grease, sweat, and the ghost of burned cordite. The tank hummed beneath them, idling like a caged animal, its 75mm gun jutting forward from the turret like a pointed accusation.

Behind Pool, the same four men who had landed with him on Omaha Beach forty days earlier waited in a silence that was part discipline, part fear, and part something harder to name.

Corporal Wilbur “Red” Riddle sat hunched in the driver’s position, hands wrapped so tight around the steering levers that his knuckles showed white through the grime. The vibration of the engine traveled up his arms into his shoulders. He could feel his own heartbeat in his fingertips.

Private First Class Bert Close manned the bow gun, listening to the faint metallic ticks of the machine and watching the world through a narrow slit of armored glass.

In the turret bustle, Corporal Willis Oller braced his boots against the floor, his arms ready, fingers hovering just inches away from the racks of 75mm rounds.

In the assistant driver’s seat sat Private Homer Davis—nineteen years old with a face that had aged ten years since June—eyes fixed ahead, lips pressed together in a line.

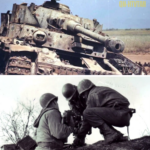

Outside, Panzerkampfwagen V Panthers waited behind a hedgerow, black crosses painted on their flanks. They were the reason American tankers woke up sweating in the middle of the night.

Panthers had five inches of sloped frontal armor and a long-barreled 75mm gun that could punch through a Sherman at two thousand yards. On paper, in every measurable category—armor, gun, optics—they outclassed Lafayette Pool’s tank.

American crews called their own Shermans “Ronsons,” after the cigarette lighter slogan: “Lights every time.” It wasn’t a joke anyone laughed at very hard.

The Germans had their own name for the M4.

Tommy cookers.

These were the odds. Three Panthers, one Sherman. Logic said get the hell out.

Pool’s hands, though, moved with the calm efficiency of a man who’d grown up fixing broken things under Texas sun. He adjusted the sight a fraction of an inch. Wind. Range. Angle.

He might have been inspecting a cotton gin back home.

“Driver,” he said, voice low and even over the intercom, “hold steady.”

Riddle swallowed and answered, “Steady, boss.”

Inside Pool’s mind, the field unfolded not as chaos, but as a pattern. Hedgerow angles, crop lines, the faint suggestion of a shallow depression in the earth where water had once pooled. The Panthers thought they were set up in the perfect killing ground. They’d guessed his direction of approach. They were wrong.

The first Panther never even knew what killed it.

In the Mood bucked as Pool squeezed the trigger. The 75mm cannon roared, the recoil hammering back into his shoulder and the turret ring. The shell traced a flat, invisible arc and slammed into the thin side armor of the Panther as it tried to shift into a new firing position.

For half a second, the German tank seemed to shudder in confusion.

Then it erupted.

The armor-piercing round touched off ammunition inside. Flames blossomed from the hatches. A secondary explosion blew the turret completely off the hull, tossing forty-five tons of steel aside like a toy. It spun through the air before slamming into the ground twenty feet away, leaving a smoking crater.

“Hit,” Oller breathed, already slamming another round into the breech.

The second Panther commander knew something was wrong. His turret spun frantically, searching for the threat he hadn’t planned for. The tank began to reverse, tracks clawing at dirt, trying to back into thicker cover in the hedgerow.

Pool spoke like he was reading a grocery list.

“Second tank, left. Engine compartment. Fire.”

Another kick. Another deafening blast.

The shell smashed into the Panther’s rear, punching through the engine compartment, and the tank lurched to a stop, immobilized. Flames licked out of the exhaust grills. Inside, five men scrambled in panic as their steel world filled with heat and smoke.

“Again,” Pool said.

The third round that morning was fired with the cold precision of a farmer putting down a wounded animal.

It entered the crew compartment and turned everything inside into fragments and fire.

The third Panther commander did the human thing.

He tried to run.

His driver gunned the engine, shoving the heavy tank forward over a small rise, trying to escape the unseen American devil that had appeared out of nowhere.

The fourth shot from In the Mood reached him as the Panther crested the rise, exposing its thinner rear armor. The 75mm round bored in and detonated deep inside. The tank lurched, then sagged. Smoke poured from hatches as it burned, another funeral pyre on Norman soil.

Less than four minutes after Lafayette Pool had fired his first shot, three of Germany’s finest tanks lay burning in the French countryside.

Inside the Sherman, there was no cheering.

Just the sound of men breathing, the clank of spent shell casings rolling across the floor, and the distant pop and rumble of other people’s battles.

“Nice shootin’, Sarge,” Riddle finally said softly.

Pool didn’t answer. He kept his eye to the sight for another heartbeat, making sure, always making sure, before he lifted his head.

He had no idea that this engagement—the first tally in what would become an eighty-one-day storm—was the opening line in the story that would mark him as the most lethal tank killer the U.S. Army ever produced.

Right now, he was just thinking about the next field.

And about the promise he’d made on a very different shoreline.

Two months earlier, Normandy had still been a rumor and a codename. Back then, it was May 23rd, 1944, and Lafayette Pool was sitting in a staging area near Southampton, England, hunched over a scrap of paper, writing to his wife.

The tent around him buzzed with low voices and the distant clatter of trucks. The smell of wet canvas and cigarette smoke hung in the air. Outside, it was that particular kind of English gray that made everything look like it was underwater.

“Dear Geneva,” he wrote, the pencil dull in his calloused fingers. “I’m fine. The food ain’t great, but the coffee’s hot.”

He paused, stared at the words, then shook his head faintly.

He did not write about the briefing they’d had that afternoon. About the blunt way the officer at the front of the tent had said, “Average life expectancy of a Sherman tank in combat? Six weeks.”

He didn’t write about the fact that the officer had not smiled when he said it.

He did not mention the dreams that had clawed at him since finishing tank gunnery at Fort Knox—dreams where he pounded on the hatch as flames licked at his boots, where his crew screamed while the metal around them glowed and sagged.

Instead, he wrote about the weather.

“It rains a lot,” he scribbled. “But the men are good. I think about you every day. Hug Mama for me. Kiss that old dog. I’ll see you when this is over.”

He stared at the period at the end of that sentence for a long time. It felt like a prayer and a lie all at once.

Lafayette had enlisted in the Army on December 3rd, 1941, four days before Pearl Harbor turned the world into something else. At twenty-one, he’d been working the family cotton farm outside Farmersville, pushing a plow, mending fences, fixing tractors with baling wire and stubbornness.

He had a farmer’s shoulders, wide and strong. A farmer’s hands, nicked and scarred. And a farmer’s steady way of looking a problem in the face and deciding not whether he liked it, but whether it could be solved.

His decision to join the military surprised no one.

“It figures,” his father had said, sitting on the porch, hat tilted back. “Boy’s always had it in him.”

Duty, for Pool, was not a speech. It was a quiet, solid thing, like a fencepost set deep in the earth.

Fort Knox turned him from a farmer into a soldier, but it didn’t take away the farmer. It just gave that stubbornness a turret and a serial number.

On the gunnery ranges, he found his place.

He didn’t just like firing the gun. He understood it.

Range estimation came to him like reading a field for where water would gather. He could look across open ground and feel—rather than calculate—the distance. He saw how wind slid across a landscape, how terrain could hide or reveal, how the sun at certain angles would betray everything.

In training, he consistently scored at the top of his class. Instructors circled his numbers on their clipboards, muttered to one another about “this Pool kid.”

It wasn’t the raw accuracy that impressed them.

It was the way he saw.

He could tell, with a glance, where an enemy might put a gun. Where a tank would sit if the man in it was smart. He described it once to an instructor as “figuring out where the deer bed down.”

The man had laughed, at first. Then he’d seen Pool’s scores again and stopped laughing.

Pool studied German tanks the way he’d once studied the habits of white-tailed deer that slipped through East Texas pines at dusk. He memorized armor thickness charts like other men memorized pin-ups. He traced silhouettes in his mind until he could recognize a Tiger or a Panther from the barest hint on the horizon.

He learned their weaknesses: thin side and rear armor, vulnerable mantlets, exposed engine decks. He understood angles, knowing how even thick plate could be cheated by the right approach.

While many American tankers were taught to think of the Sherman as cavalry—fast, maneuverable, meant to exploit breakthroughs and avoid slugging matches—Pool approached tank warfare as a hunter who couldn’t afford to be a prey animal, ever.

“Biggest gun don’t always win,” he told a fellow trainee once, leaning against a warm engine. “Fella who fires first and hits first does. That’s who walks away.”

His instructors wrote notes in margins.

Exceptional situational awareness.

Predatory instinct for targets.

And underneath, in one script: “We’re going to send this boy where the fighting’s thickest.”

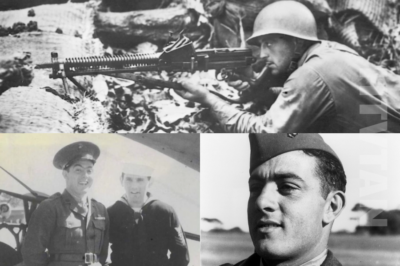

In those same months, his crew came together like parts in a machine that no one quite believed was as good as it turned out to be.

Red Riddle came from a Pennsylvania farm not so different from Pool’s in Texas, except the corn was taller and the winters meaner. He had the same patience, the same ability to sit for long hours on a tractor or, now, behind a steering lever.

He drove like a man who understood that sometimes an inch left or right meant the difference between cover and catastrophe.

Bert Close, a mechanic from Michigan, could coax an engine back to life with cursing and wire. He’d grown up in the shadow of Detroit’s factories, knew what machines could take before they broke. In In the Mood, he watched dials, listened to faint ticks, smelled for overheating bearings the way other men smelled for rain.

Willis Oller was the youngest, barely more than a boy when he joined them. His hands, though, were fast. He could slam a 75mm shell into the breech with a rhythm that was almost musical—heel, twist, shove, hand out of the way before the breech block dropped.

Homer Davis rounded out the crew. His job was the bow gun, but his other job was being nineteen and somehow still soft inside, even with war hardening him from the outside. He helped navigate, watched the right front, kept their world just a little bigger than what Pool could see through his sight.

They came from different states, different backgrounds, different churches. But the first time they ran a live-fire maneuver together, something clicked.

Commands came out of Pool’s mouth before he even knew he was saying them, and the others responded as if they’d heard them before.

“Neutral steer—now. Loader, AP. Bow gun, right ditch. Driver, three yards forward, angle right.”

No one hesitated.

When the instructors timed them on a complete cycle—spot, aim, load, fire—they clocked In the Mood’s crew at under six seconds.

“Damned if I know how they do it,” one officer said, shaking his head. “But I’m not arguing with it.”

June 6th, 1944, Omaha Beach.

The official record says it was part of the Third Armored Division’s 32nd Armored Regiment, that In the Mood rolled off a landing craft into three feet of frigid water with white letters painted on her gun barrel spelling out her name.

The men inside remember the smell.

Burning vehicles. Shattered equipment. The heavy, copper stink of blood in salt water.

From the driver’s slot, Riddle watched the landing craft ramp clang down and thought for an instant that the whole world was red light and noise.

Machine-gun rounds snapped overhead, invisible and very real. Men were running, falling, crawling. The beach was a churned mass of crater lips and broken metal.

“Forward,” Pool ordered, his voice strangely calm over the intercom.

Riddle shoved the levers. The thirty-three-ton tank lurched into the water. The cold came up through the hull, through their boots.

Homer, in the bow, watched the waves slap against the front slope, bodies bumping against it before sliding away.

In the Mood climbed out of the water and onto sand, her tracks biting in. She dodged craters and burning tanks, weaving as much as a lumbering machine could weave.

Pool had his eye to the sight, not because he expected to engage a tank, but because that gun sight gave him a circle of clarity in the chaos.

Inside that circle, he saw fighting positions, obstacles, a path.

In that moment, watching men die all around him, he made a silent promise.

I will get these boys home.

Whatever it takes.

He didn’t tell them.

He showed them, day by day.

June 18th, near Villiers-Fossard.

The Norman countryside was nothing like the maps. On paper, it was fields and roads. In reality, it was a green labyrinth designed to kill tanks.

The bocage.

Ancient hedgerows that weren’t hedges at all, but earthen embankments topped with roots and stone and vegetation thick enough to hide a tank behind, or inside, or under. Fields were small, crooked. Roads were sunken, with banks rising on either side like the walls of a trench.

American tankers had trained for open ground. They’d imagined battles where they could see the enemy at a mile, where they could maneuver freely.

Instead, they were pushing through tunnels of dirt and leaves, every corner a question mark.

Pool’s platoon—five Shermans in staggered column—rolled along a sunken lane, guns swung left and right, nerves strung tight.

It happened fast.

The lead tank exploded in a sudden gout of flame, a great orange flower blooming over the hedgerow. The shockwave hit In the Mood a moment later, a hot slap of air.

“Panzer!” someone yelled over the radio. “Panzer in the hedge!”

A Panzer IV, dug into a gap in the hedgerow less than fifty yards ahead, had been waiting with its gun zeroed on that exact stretch of road. Its first shot had punched through the Sherman’s frontal armor like it was tin, detonating the ammunition stored along its sides.

Four out of five crew members died before they even knew they’d been hit.

The driver crawled from the wreck, skin hanging in strips, burning from head to toe. He would live three days in a field hospital before mercifully letting go.

The second Sherman in line tried to reverse. There was nowhere to go.

The road was too narrow. The banks too steep. The panic too real.

The Panzer’s second shot turned that tank into another furnace.

Inside In the Mood, the crew felt like they had been shoved to the edge of a cliff.

“Back up!” Oller shouted unconsciously.

“Get us out!” someone else yelled.

Pool looked, just once, through the sight.

He saw the Panzer’s muzzle flash still glowing. He saw the narrow slice of road. He saw something else.

On the right side of the lane, halfway between his tank and the burning wrecks, a gap in the hedge—not visible from the road until you were almost on top of it. A wider spot. It wasn’t much. But it was something.

He had two choices.

Reverse into the jam of wrecks and probably die.

Or go forward into hell and maybe live.

“Driver,” he said, voice steady as if he were asking for a cup of water, “full speed ahead.”

Riddle slammed the accelerator.

The Sherman lurched forward, its engine roaring. They thundered past the burning tanks, close enough that heat seared the paint on In the Mood’s hull.

“Hard right!” Pool barked.

The tank smashed into the gap in the hedgerow. Branches scraped the hull, roots shoved against the belly. For three seconds, they were blind. Dirt and vegetation filled Pool’s sight picture.

Then they broke through.

Field. Open, green, and suddenly full of possibility.

Pool swung the turret.

The Panzer IV that had destroyed two of his tanks was sitting in profile now, its flank broad and vulnerable just thirty yards away.

“AP,” Pool said.

“Up!” Oller shouted, slamming the armor-piercing round into the breech.

Pool fired.

The shell hit the turret ring, the narrow band that allowed the turret to traverse. Armor shattered. The turret jammed, the German gun frozen halfway through a traverse.

The second shot came four seconds later. It punched through the side armor into the ammunition racks.

The Panzer went to pieces.

Men on the lane, still pinned behind wrecks, saw the German tank burst apart, turret lifting, flames blooming.

They would later swear it had to have been artillery. No single tank could do that, that fast.

But Pool was already turning his sight.

He’d spotted something else.

Three hundred yards away, in a line of trees, a Panther sat hull-down, just its upper structure visible. It had been watching the slaughter on the sunken road, its commander focused on the easy targets in front of him.

He hadn’t seen the Sherman crash through the hedge.

“Panther, twelve o’clock, three hundred yards,” Pool said. “AP. Mantlet.”

Oller loaded. Close adjusted the tank’s hull to give a better angle. Riddle kept the engine revving, ready to juke.

Davis swung his bow gun toward a squad of German infantry in a ditch, finger resting on the trigger.

Pool fired.

The round struck the Panther’s gun mantlet, one of the few weak spots on its face. It ricocheted downward, burrowing into thinner armor.

Inside the Panther, the driver died before he even understood what had happened. The tank lurched forward, out of control, smashing into a stone wall.

“Hit again,” Pool said.

The second shot, at the now-immobile target, was no test at all.

The Panther died, its crew dying with it.

Later, Captain James Bates wrote in the after-action report that what he’d witnessed defied belief. The timing. The moves. The way In the Mood had turned a slaughter into a hunt.

It wasn’t luck.

It was a pattern repeating itself, over and over, for the next eighty-one days.

By July 7th, three weeks into the campaign, Pool’s crew had destroyed nineteen German armored vehicles.

Nineteen.

For most tank crews, that would have earned a trip to the rear, a safe instructor’s post, and enough medals to weigh down a uniform.

Instead, Third Armored Division Headquarters drew a circle around their tank number and wrote a single decision next to it.

Use them.

The more dangerous the mission, the more likely In the Mood was in the lead.

Word spread.

“Stick close to War Daddy,” one tanker told another over mess tin coffee. “He’ll get you through.”

Some crews requested to be assigned near Pool’s platoon. It wasn’t superstition, exactly. It was something close to it. In a world where steel and chance ruled, any hint of a pattern—a man who lived when others died—was something to cling to.

Reality was less mystical than the stories.

The bocage was chewing up Sherman crews at a sickening rate. Engagement ranges averaged under three hundred yards. At that distance, German guns were essentially guaranteed kills. Shermans burned like kindling when hit.

A study from an Army operational research section would later quantify it.

In the summer of ’44, the life of a Sherman crew in Normandy could be measured in days, sometimes hours.

Pool’s insistence on hunting instead of waiting became more than a preference.

It became survival.

He refused to drive his tank down a road just because the map said it was there. Even when ordered to.

“Find me another way,” he’d tell Riddle. “Roads are where they expect us.”

The hedgerows, those damned green walls that had trapped and killed so many, became his doors. He used In the Mood’s bulk like a battering ram, punching through at points no one would have thought possible.

He studied the countryside with an eye that had once studied woods for signs of deer.

He learned to spot disturbed vegetation, track marks too fresh to be old, the faint blue haze of exhaust that hung in still air long after an engine idled.

Most of all, he believed in moving fast when others hesitated.

“A Sherman can’t slug it out with a Panther or a Tiger,” he told a Stars and Stripes reporter later. “We’d lose every time. But if you hit ’em first, hit ’em hard, and hit ’em before they know you’re there, you can kill any tank they’ve got.”

He lived that philosophy.

So did his crew.

On a morning north of Saint-Lô, they were tasked with clearing a series of fields. Intelligence said elements of Panzer Lehr—one of Germany’s elite armored divisions—were in the area.

The briefing was short.

“Gentlemen,” Captain Richard Foster said, tracing a line on the map with a finger, “we need those fields cleared by nightfall. Good luck.”

The first field yielded nothing but the wreckage of an earlier fight.

Burned tanks—German and American—lay like discarded toys.

The second field was empty, save for a few abandoned positions.

In the third field, Pool’s instincts prickled.

The air felt heavier. The silence different. He had Riddle advance cautiously, In the Mood nosing up to a hedgerow.

Pool peered through his sight.

There they were.

Five German tanks. Two Panthers. Three Panzer IVs. All tucked into a hedgeline, hulls low, guns facing north—the direction they expected Americans to come from.

Pool wasn’t coming from the north.

He’d smashed through two hedgerows that “no tank could go through.” He was now east of them, looking at their broadside from four hundred yards.

He didn’t hesitate.

“AP,” he ordered.

The first shell left the barrel with a flat crack and slammed into the nearest Panther. It struck the hull near the ammunition racks. The tank vanished in a blooming fireball, armor plates lifting, turret twisting.

Before the other tanks could even finish starting to traverse their turrets, Pool fired again.

The second round tore into a Panzer IV’s tracks, blowing road wheels off and dropping the tank onto its belly, immobile. It couldn’t move, couldn’t reposition its gun.

Inside the German hedgerow position, chaos erupted.

The close confines that had seemed so perfect when they’d imagined ambushing Americans now trapped them. One Panzer IV tried to back up, ramming into the tank behind. Turrets banged into branches. Engines stalled. Commanders yelled at drivers who had nowhere to go.

“In the Mood is chewing ’em up,” a stunned American infantryman watching from a distance would later say. “It was like shootin’ cows in a pen.”

Pool’s third and fourth shots destroyed the two immobilized tanks. Flames licked up. Ammunition inside cooked off.

The last Panther, commanded by someone who understood that no amount of bravery could save him in that box, backed out and ran.

It fled directly into the guns of Sergeant John McVey’s Sherman from Pool’s platoon.

For the men in those tanks, it was another hot, terrifying day.

On paper, it was another notch in a ledger that would soon look impossible.

July 29th, Operation Cobra broke the stalemate.

It began with the sky turning into a weapon.

More than two thousand Allied bombers roared overhead and carpet-bombed German positions west of Saint-Lô, tearing a five-kilometer-wide corridor into the German line. The bombardment shattered earth, trees, men, and machines alike.

When the dust settled, the order was simple.

Drive south. Kill anything with a swastika on it. Don’t stop until you see Germany.

The hedgerow war became a war of movement.

That should have favored the Americans. It did, in the big picture. In the small picture—the one occupied by men like Pool—it was just a different flavor of lethal.

German units, reeling from the bombardment, fought like wounded animals. Panzer crews launched counterattacks from burning villages. Anti-tank guns appeared at crossroads, in farmyards, on ridgelines.

In the Mood led again and again.

The tally climbed.

By August 2nd, they’d knocked out forty-three German vehicles.

By August 5th, sixty-one.

By August 10th, ninety-two.

Numbers. Just numbers. Each one a tank or gun or armored vehicle that would never fire again.

Inside the Sherman, the price was being paid in other kinds of numbers.

Sleep came in two-hour snatches, grabbed wherever they could park under concealment. Food was whatever rations they could cram into their mouths while engines idled. Coffee was a religion.

Red Riddle’s hands were a map of burns and cuts. Hot brass from ejected shells had kissed his skin more than once. Infection set in under fingernails ripped by hurried maintenance.

Bert Close lost fifteen pounds he couldn’t really spare, sustained on black coffee, cigarettes, and adrenaline.

Willis Oller developed a cough from breathing cordite fumes in the confined turret, hacking into his sleeve between loads.

Homer’s words dried up. He spoke only when he had to, his gaze growing distant. The thousand-yard stare set into his face like lines carved in stone.

And yet, strangely, Pool seemed to get sharper.

The more he saw, the more he sensed.

“War Daddy’s got a sixth sense,” men started saying.

On three occasions, he ordered abrupt course changes—“Right. Now.”—seconds before German anti-tank guns opened from the path they’d been about to take.

Twice, he called out German tanks lying in ambush that no one else could see. No telltale movement. No sunlight glint. He just knew.

It felt supernatural to those around him.

The reality, he explained later, was less magic and more math.

He had studied German habits the way he’d studied whitetail deer. He knew where a smart man would put his tank. Where he’d put a gun. He read terrain like text, saw tire ruts that others missed, smelled exhaust on still air.

Most importantly, he trusted that tight knot in his gut that every hunter learns to trust: something’s wrong.

“Your eyes don’t know yet,” he’d say. “But something in you does. You’d better listen.”

On August 14th, 1944, his instincts and his courage collided with forty-five tons of German steel and the worst odds he’d yet faced.

They were advancing near a town whose name blurred in the reports—Chambray, Chambois, some French syllables that would only ever mean “danger” to the men who were there.

Pool saw it first through his sight: a Tiger tank off the road, parked in a stand of trees six hundred yards ahead.

The Tiger was the monster of campfire stories.

An 88mm gun that could kill a Sherman at over two thousand yards. Four-plus inches of armor on its nose that a 75mm round might as well bounce off of. It weighed fifty-six tons and carried a reputation that weighed even more.

This one looked dead. It sat half-sideways, barrel angled slightly off, no visible crew movement.

Pool didn’t trust it.

“Hold,” he ordered.

Riddle eased off the throttle. In the Mood idled, engine rumbling.

Pool studied the scene through his sight.

The Tiger’s position bothered him. It was too obvious. Too inviting. A big, juicy target for a gunner to claim. It was exactly where someone would put a dead tank if he wanted to make you look the wrong way.

His eyes slid to the right.

There. A hedgerow. A subtle disturbance in the leaves. A faint glimmer of metal, easily missed.

Something moved.

Another Tiger emerged, this one very much alive, maneuvering through cover to catch In the Mood in a crossfire. The plan was clear: lure the Sherman’s attention to the “dead” tank, then kill it from the flank.

Pool had two seconds, maybe three, to decide.

Head-on against either Tiger was suicide. His gun couldn’t beat their armor from the front.

Backing up would expose their thinner rear armor.

“Driver,” he snapped, “hard right, into that hedge! Move, move, move!”

Riddle didn’t ask questions. He hauled the levers.

The Sherman jumped forward and right, smashing into the hedgerow like a bull through brush.

Branches scraped, roots thumped. For a moment, there was nothing in Pool’s sight but green and brown and blurred motion.

Then—

They dropped into a shallow depression.

“Hold,” Pool said.

Riddle cut power, letting the tank settle.

They were in a field, low in a slight fold of ground. The depression hid most of In the Mood’s hull. Only the top of the turret and the gun stuck up, and even that was partially obscured by brush.

Pool’s heart hammered. He forced his breathing steady.

“Everybody still here?” he asked.

“Yeah,” Oller said.

“Present,” Close muttered.

Homer said nothing, but his hand tightened on the bow gun grips.

For two minutes, they sat absolutely still.

Through the narrow cracks of their periscopes, they heard the Tigers rumbling past on the road they’d just abandoned. The deep growl of Maybach engines, the clatter of heavy tracks.

“We’re dead if they see us,” Close murmured.

“Shut up,” Oller hissed. “They won’t.”

Pool didn’t answer. He was watching through the tiniest gap in the hedge.

One Tiger rolled past, continuing down the road, searching for the Sherman that had vanished.

The second turned, heavy nose pointing toward the gap In the Mood had smashed through.

It rumbled closer. Seventy-five yards. Fifty.

It stopped.

The commander stood in the open hatch, black panzer uniform neat despite weeks of retreat, collar tabs marking him as a Hauptmann—a captain. He raised binoculars to his eyes and began to scan the field.

Slowly. Methodically.

Pool tensed.

The German’s binoculars swept past the depression.

Then swung back.

Pool saw the moment recognition hit. The Tiger commander stiffened, binoculars jerking an inch. His mouth opened, hand dropping toward the intercom throat mike.

“Now,” Pool whispered.

He fired.

At seventy-five yards, the Tiger’s side armor might as well have been paper.

The armor-piercing round smashed through the sponson and into the crew compartment. The explosive filler detonated inside, turning the interior into a storm of fire and metal.

The Hauptmann died instantly. One second alive in his hatch, the next gone in a splintering blast.

Inside, the rest of the crew never had a chance. The tank became a furnace, a pillar of thick, black smoke rising into the sky.

The first Tiger, hearing the explosion, began to reverse, then reconsidered and moved forward, trying to find a position.

Its commander still didn’t know exactly where In the Mood was. Smoke and hedgerow masked them.

He made a mistake.

He turned sideways, presenting his tank in profile as he advanced back up the road.

“Tracks,” Pool said. “Two hundred yards.”

He fired.

The first shot chewed through the Tiger’s near track, blowing it apart. The tank lurched, sagging sideways, immobilized.

The second round went into the rear hull. Fire sparked in the engine compartment and began to spread.

The third punched into the turret ring, jamming it. The Tiger could no longer swing its 88, could no longer elevate or depress its gun.

Inside, the crew understood. They bailed, jumping from hatches, uniforms smoking.

Pool watched them through the sight: five men stumbling away from their dying machine.

He did not shoot.

“We kill tanks,” he said later. “Not men with their hands up.”

The German tankers, stunned to be alive, raised their hands and walked toward American lines.

That evening, in a field that smelled of crushed grass and burnt metal, while In the Mood’s crew cleaned guns and checked tracks, Captain Foster arrived.

He carried a bottle of German schnapps and something else.

“War Daddy,” he said, as Riddle and Close looked up, “the general wants to see you.”

“General who?” Pool asked, wiping his hands on a rag.

“General Rose,” Foster said. “The one in charge of the whole damned division.”

Major General Maurice Rose had made a name for himself as one of the most aggressive armored division commanders in the European theater. He was the son of a rabbi and had earned his commission in the last war. He understood blood and steel better than most.

Division headquarters sat in a commandeered French farmhouse, its plaster walls chipped by shrapnel, its yard churned by tank tracks. Maps covered tables inside. Cigarette smoke hung under the low ceiling like fog.

Pool stood at attention in a uniform that still smelled faintly of engine oil.

Rose held a sheet of paper covered in typed lines.

“Sergeant Pool,” Rose said, his voice carrying a faint Colorado accent. “I’ve been commanding armored forces since before you were born. I’ve seen good tank crews. I’ve seen lucky tank crews.”

He looked up, eyes sharp.

“You and your men are neither. You’re the best damned tank killers in this entire army. And I want to know how.”

Pool shifted slightly, uncomfortable with the praise.

“Sir,” he said, “we hunt ’em like deer. We learn their habits. We find their hiding spots. And we shoot first. That’s all there is to it.”

Rose stared at him for a long second.

Then a slow smile tugged at the corners of his mouth.

“That,” he said, “is the most honest tactical assessment I’ve heard since we landed on this godforsaken continent. Carry on, Sergeant. Keep your crew alive. Keep killing German tanks.”

The general’s endorsement had consequences.

Soon, a man from Stars and Stripes turned up, notebook in hand, photographer in tow.

“The Texas farmer who’s giving Hitler’s panzers hell,” the article called him.

Pool hated it.

He hadn’t come to Europe to be a hero in print. He was here to do a job and get his boys home.

But the article spread through the ETO like a campfire rumor.

American tankers who had looked at their thin armor and cursed the Shermans suddenly had a counter-story to the one that said they were just living in deathtraps.

If a farmer from Texas and his four men could do what the numbers said they’d done, maybe it wasn’t suicide every time they engaged a Panther.

Maybe it was possible.

September 19th, 1944, they crossed into Germany.

The Shermans’ tracks ground over a border that had once seemed impossible to reach. The war had moved fast after Normandy. France had fallen in a blur of hedgerows and villages and open country.

Yet the swiftness of the advance came at a cost.

Fuel convoys struggled to keep up. Ammunition stocks fluctuated. Tanks outran their supplies and had to sit in fields, impotent, waiting for gasoline.

For a few weeks, there was talk of “home by Christmas.” For a few weeks, it felt like momentum might carry them all the way to Berlin before the snow.

Then the line stiffened.

The war settled into a grinding push against the Westwall, the Siegfried Line. Pillboxes and dragon’s teeth. Mines and anti-tank ditches. The borderlands of Germany were built to be a meat grinder.

By the outskirts of Aachen—the first major German city facing the Allied advance—Pool’s tally had reached 212 confirmed kills.

Inside the division, the legend of In the Mood had grown bigger than the tank.

Some said Pool could see through hedgerows.

Others swore he’d made a deal with the devil.

Pool would have rejected all of it.

“We’re just good at what we trained for,” he’d say. “And we’re lucky.”

Aachen tested them differently than the bocage or the open fields of France.

Urban combat stripped away range and maneuver. Narrow streets funneled tanks into obvious lines of fire. Every window, every cellar, every doorway could hide a man with a Panzerfaust—a disposable, shoulder-fired shaped-charge rocket.

The Sherman’s armor, thin enough already, meant nothing against a Panzerfaust at fifteen yards.

On September 29th, 1944, In the Mood rolled down a rubble-strewn street, supporting infantry assaulting a factory complex.

The city was a shattered maze. Entire buildings had collapsed into the street. Smoke drifted between cracked walls. The sound of small-arms fire echoed, mixed with the deeper barks of guns and the occasional scream.

Pool scanned.

A Panther appeared from a side street, so close he could smell its exhaust—less than a hundred yards away. Its gun swung toward them.

“Panther!” Oller yelled.

The German commander fired in haste, spooked by the sudden encounter. The round struck the Sherman’s turret at an angle, glancing off with a shriek of metal. The impact rocked the tank. Inside, the crew’s teeth snapped together.

For a moment, Pool saw nothing but spinning colors.

Oller, ears ringing, had already rammed another shell into the breech. His body did what it had done a hundred times before.

Pool shook his head clear, found the sight again.

The Panther filled his view.

He fired.

At that range, there was almost no chance of a miss. The round smashed through the German tank’s thinner side armor. Flames burst from the hatches as ammunition detonated.

It was their 258th confirmed kill.

Two hundred and fifty-eight German tanks and armored vehicles destroyed in eighty-one days of continuous combat.

No American crew has ever matched it.

Three hours later, their luck ran out.

They never saw the team that killed In the Mood.

The Sherman rolled forward, leading infantry up another torn-up street. Piles of brick and twisted rebar lined both sides. Windows were vacant, gaping. Basement openings were black mouths.

In one of those basement windows, fifteen yards away, a German soldier crouched with a Panzerfaust on his shoulder, waiting for the exact angle where the Sherman’s nose would fill his world.

He fired.

The shaped-charge warhead struck the front hull and punched through. Armor that had turned rifle rounds and shrapnel became tissue paper against a jet of superheated gas.

Inside the tank, the explosion was a thunderclap. Fire roared through the crew compartment. Shards of metal flew like bullets.

Homer Davis died instantly.

The blast cut him down where he sat in the assistant driver’s seat.

Pool and Close were shredded by shrapnel, burns searing their skin. Pool felt his legs vanish under him in a wave of pain and heat.

Flame erupted around them.

Red Riddle, his arms and face burning, clawed at his harness, slammed his shoulder into the driver’s hatch, and forced it open.

“Get out!” he screamed. “Get out!”

Oller swung the turret to give himself room, ignoring the fire licking at his sleeves, and grabbed Pool, dragging him toward the hatch.

Outside, infantrymen saw the tank belch fire and smoke, heard the screams.

They ran forward into the kill zone, rifles snapping, firing into the basement window where the Panzerfaust team had already melted back into the building.

Riddle hauled Pool out onto the hull, skin blistering, lungs searing with smoke. Close stumbled behind, half-blind.

Machine-gun fire rattled as American troops poured lead into every dark hole along the street.

By the time medics reached them, the flames reaching for In the Mood’s ammunition racks were already cooking off rounds.

Pool drifted in and out of consciousness as they loaded him on a stretcher. He heard Riddle’s voice somewhere, saying something he couldn’t quite catch.

In later retellings, someone said that even as medics worked on him, Pool asked if the main gun was still usable.

If true, it was less bravado than habit.

His mind, even broken and burning, still thought in terms of the fight.

He survived.

Barely.

He would never fight from a tank again.

They evacuated him to a field hospital in Belgium, then to England, and finally across the ocean, back to a military hospital in the United States.

The doctors patched him up as best they could. Burns. Shrapnel. Damaged limbs. His body healed in ways that made walking painful and heavy work harder, but it healed.

His crew did not all get that chance.

Riddle recovered enough to return to combat with another crew. He drove a different Sherman, in different battles, and somehow lived through it all, returning to Pennsylvania and the fields that waited for him.

Oller went back, too.

He died in December 1944 during the Battle of the Bulge, killed when a German anti-tank round turned his Sherman into the same kind of blazing coffin he’d escaped months earlier.

Close survived, body scarred, lungs never quite right again. He spent the rest of his life wrestling with injuries you could see and wounds you couldn’t—flashbacks, nightmares, the phantom smell of burned steel. He found purpose working with other disabled veterans, guiding them through their own long recoveries.

Homer stayed behind.

He was nineteen when they buried him under a white cross in a military cemetery in Belgium, one of thousands of identical markers. His family would visit once, years later, tracing his name with their fingers, trying to imagine the boy who’d left home and never come back.

In the Mood, stripped of usable parts, was scrapped. Cut up. Melted down.

No one thought to preserve it.

In 1944, everyone wanted the war to be over, not turned into a museum.

November 11th, 1945.

Veterans Day.

Pool stood on the platform of a small train station in Farmersville, Texas, duffel bag slung over one shoulder, uniform hanging a little looser than when he’d last worn it. Silver Star. Two Bronze Stars. Purple Heart.

The war in Europe had ended six months earlier. The war in the Pacific was over now, too. The papers were full of new words—atomic, mushroom cloud, Cold War.

He stepped down onto familiar dirt and had to stop for a second as the smell hit him.

Not cordite.

Not diesel.

Not burning flesh.

Just Texas.

Dry earth. Cut hay. Distant wood smoke.

Geneva was there, dress simple but pressed, hair done the same way she’d worn it in the picture he’d carried in his pocket through Normandy. She walked toward him, eyes bright, and for a moment he felt like he was looking at her from far away, through a gun sight.

Then she was in his arms.

He held her and felt something in his chest unclench.

People shook his hand, clapped him on the back, told him they were proud. The town had a small ceremony, a few words from the mayor, an American flag snapping in the breeze.

Pool smiled when he was supposed to. He thanked them.

Then he went home.

The nights were harder.

Back in his own bed, in a quiet house, the war wasn’t gone. It was waiting behind his eyelids. Tigers in fields. Panthers in hedgerows. The explosion that took Homer.

He woke up sweating, heart pounding, lungs dragging at air that smelled like smoke even when it didn’t.

Back then, no one talked about PTSD. They called it combat fatigue or shell shock. They told men to toughen up. To put it behind them.

He did what he’d always done.

He worked.

He went back to farming.

There was a comfort in the simple, repetitive violence of plowing, planting, harvesting. The land demanded attention in ways he understood. No one shot at him from a hedgerow. No one ordered him to clear a field of Panthers.

Geneva never pressed him for details.

She saw the way his hands shook when a car backfired. The way his eyes sometimes went blank at the sound of thunder. She made coffee, sat beside him on the porch, and let silence do its work.

He found his footing again in the small things.

Fixing a broken fence. Helping at church. Talking to a neighbor about a sick calf. Being present at the dinner table. Laughing, once in a while, real laughter that didn’t feel brittle.

His name faded from the papers.

The country moved on, as countries do. The war became memory, then history, then something kids learned about in school with dates and arrows on maps.

Pool didn’t mind.

He’d never wanted to be famous.

He just wanted to have done his job and gone home.

Historians did not forget him.

They dug into Third Armored Division’s records, into after-action reports, into the scribbled notes of operations sections who’d tried to keep count while chaos roared around them.

They found the numbers.

Two hundred and fifty-eight German tanks and armored vehicles destroyed in eighty-one days of combat operations by one crew and their commander.

Military scholars compared that tally to entire companies, entire battalions.

He had outperformed some of them by himself.

More remarkable than the destruction was the survival.

Until that Panzerfaust in Aachen, Pool’s crew had lost just one man in all those days of battle—Homer, in that final blast.

In a theater where three out of four Sherman crews became casualties, that statistic looked as miraculous as the kill count.

Analysts broke it down.

Aggression that seized the initiative instead of cowering from superior German armor.

Terrain reading that allowed him to set ambushes instead of blundering into them.

Crew cohesion that turned five men and one tank into a single organism.

They wrote his name into books with careful footnotes.

They talked about how his success undermined the idea that American armor had been hopelessly outclassed.

German tanks were better on paper, yes. Thicker armor. Bigger guns. Better optics.

But Pool showed that tactics could bend that gap, sometimes break it entirely.

In an interview in 1983, a military historian asked him how he wanted to be remembered.

He shrugged.

“I was just a soldier doing my job,” he said. “Nothing special about it. I had a good crew. We were trained well, and we were lucky. That’s all there is to tell.”

It wasn’t all there was to tell.

But it was exactly how he saw it.

He died on May 21st, 1991, at seventy years old.

Farmersville laid him to rest under a simple headstone. Name. Dates. Rank. Unit.

No mention of tank ace. No list of kills. No reference to Normandy, to France, to Germany.

Just stone and grass and sky.

It fit him.

Friends knew him as a man who showed up when something needed doing. Church projects. Veterans’ events. A neighbor’s barn that needed raising. He was the quiet one in the back, doing heavy lifting without needing his name on a plaque.

People who’d known him for years sometimes only found out about his combat record after he died.

“The old man?” they’d say, stunned. “The one who brought casseroles to funerals? That was him?”

Yeah. That was him.

The Texas farmer who’d hunted panzers like deer and led the most lethal tank crew in U.S. history.

The story of Lafayette Green Pool and the crew of In the Mood isn’t just about numbers on a page or tanks burned in fields half a world away.

It’s about five ordinary Americans from farms and small towns who were handed a thirty-three-ton machine and told to step into the ring with monsters.

It’s about a farmer who learned to read battlefields the way he once read weather.

About a driver whose hands bled on steel levers and never quite healed.

About a loader who moved shells like a man bailing out a sinking ship, every round another heartbeat bought.

About a nineteen-year-old bow gunner who never got the chance to grow old.

About a mechanic who spent the rest of his life helping other broken men rebuild themselves.

Their Sherman is gone. Its metal is part of something else now. A ship. A building. A car. No museum has its hull. No glass case holds the gun barrel that spelled out its name.

But in armor schools, instructors still talk about Pool.

They teach young tankers to move fast, to think like hunters, to hit first and hit hard.

They remind them that discipline, aggression, and crew cohesion can do what raw firepower alone cannot.

They tell them about a Texas farmer who stared through a gun sight at a world on fire and made a promise to get his boys home.

He didn’t save all of them.

No one could.

But for eighty-one days, in a summer when the fate of the world was an open question, he and his four-man crew turned a Ronson into a scalpel and carved through the heart of Hitler’s armored fist.

Two hundred and fifty-eight times, a German tank or gun went up in flames because of them.

Each one lessened the weight on an American infantryman’s shoulders. Each one made it just a little easier for somebody else to live.

In the end, that was the measure that mattered.

Not the legend. Not the headline.

Just a farmer who became a warrior, who did his terrible work with skill and care, who came home when he was done and went back to the land.

And somewhere, in the way American armor fights today—fast, aggressive, trusting its crews and their instincts—you can still see his shadow moving across a field, sight lowered, breath steady, finger tightening on the trigger one more time.

News

CH2. They Mocked His ‘Cheap’ Machine Gun — Until John Basilone Stopped 3,000 Soldiers With it

They Mocked His ‘Cheap’ Machine Gun — Until John Basilone Stopped 3,000 Soldiers With It The darkness over Guadalcanal on…

CH2. They Laughed at His ‘Mail-Order’ Rifle — Until He Killed 22 Japanese Snipers in 7 Days

They Laughed at His “Mail-Order” Rifle — Until He Killed 22 Japanese Snipers in 7 Days January 22nd, 1943. Guadalcanal,…

CH2. A Submarine Drone Just Found a Sealed Chamber in the Bismarck — And Something Inside Is Still Active

The first thing they saw was the heat. At nearly five thousand meters down, there wasn’t supposed to be any….

CH2. Japan Laughed at America’s “Toy Bomb” Then the Ocean Turned Into Fire

Japan Laughed at America’s “Toy Bomb” Then the Ocean Turned Into Fire It began with laughter. Not the warm, human…

CH2. US Navy Wiped Out Japan’s Fleet in 40 Minutes

US Navy Wiped Out Japan’s Fleet in 40 Minutes The men on Yamashiro could not see their enemy. They could,…

CH2. Germans Couldn’t Believe One “Fisherman” Destroyed 6 U-Boats — Rowing a Wooden Boat

Germans Couldn’t Believe One “Fisherman” Destroyed 6 U-Boats — Rowing a Wooden Boat May 17th, 1943. North Atlantic dawn. The…

End of content

No more pages to load