The Father Weeps at His Daughter’s Grave, Unaware That She Is Watching Him

Part I

The wind sank into the cemetery like a sigh no one wanted to claim. Cypress branches arced above a small white gravestone and made a chapel out of shade, and a man in a wrinkled suit knelt before it as if he were both penitent and accused. He pressed his palms over his face. He shook. When he lowered his hands the stone remained: smooth, implacable, engraved in a language that carried the cadence of lullabies and funerals alike. A photo had been etched beside the words—a girl whose eyes smiled with mischievous light, whose hair seemed to be caught by a breeze that no longer existed.

He came every Sunday, always with white lilies that trembled on their stems the way his voice trembled when he whispered to the air. His name was David Romero, and in the small repair shop he owned, he once kept time by the whirr of belt sanders and the punctual tick of clocks he had rescued from attics. But his true clock had been his daughter, Isabella, whose nine-year-old chatter marked the hours between morning cereal and bedtime stories. She had drawn flowers on every grocery receipt, every folded napkin, even the dust on the dashboard of his truck—tiny suns with petals and a face, always smiling. She had promised him, with the unbreakable confidence of a child, that she would become an artist famous enough to paint the sky.

Then the sky shattered. A storm crawled over the town; the streets glassed with rain. David worked late because a customer had begged him for a miracle—could he fix the old register before Monday? He could. He did. And he missed the school play he’d sworn he would not miss.

On the drive home, Maria—his wife, steady as a lighthouse, softer than a warm loaf—buckled Isabella into the back seat, promising hot chocolate and a movie. On the intersection near the bakery, a distracted driver read a text message and drove his steel cage through the red light like a blind god. The impact was hungry, immediate. Lights. Sirens. A hospital so bright it erased the world. Isabella’s hand small on the sheet, then not there at all.

The mind, when struck, becomes a bird that slams against glass again and again. For two years after the funeral, David lived in a season without calendars. He measured time by visits to the cemetery, by the number of lilies withering in a vase on his kitchen table, by the syllables of apologies muttered to no one. Maria grasped his arm until her own grief asked for space and a locked door in a new town. She left with a suitcase of clothing and an entire body of love she could not carry without drowning.

David remained. He woke early, brewed coffee he forgot to drink, wiped grease from wrench handles that no longer warmed to his touch, and on Sundays he walked to the graveyard as if the earth itself had looped a leash around his heart and tugged him there.

He didn’t know he was being watched. He didn’t know a shadow under an old oak contained a pair of eyes that stayed with him even after he left. She had been careful at first, the girl under the tree. She came because the cemetery was quiet in a way that wasn’t cruel. Her name was Elena, and sixteen years had taught her how to survive the noise of kitchens where plates flew like planets thrown out of orbit, the noise of midnight arguments that made the walls thin as tissue, the noise of car doors slamming while adults with court-issued smiles promised a better placement next time.

In foster homes you learned small truths: to fold your blankets crisply so no one would read disorder as defiance; to keep your backpack ready for inspection because you were always about to be moved; to build a room in your mind that locked from the inside and contained a lamp and a glass of water when the real house flickered dark. In that room she made drawings—flowers that refused to wilt, skies that were not storms, hands that reached without grabbing. The cemetery’s hush felt like an answer when life had been one long question.

She saw him there a handful of Sundays before she found the courage to read the name etched in stone and say it out loud under her breath. Isabella. The sound made something in Elena unclench. Not all losses come with funerals. Some arrive with new houses that smell like someone else’s soap and the word temporary pinned like a name tag to your chest. But grief recognized grief. It didn’t insist on a pedigree.

The next Sunday, she left a drawing. She used the small tin of colored pencils a counselor had bought her from a pharmacy, their tips already shortened by a summer’s worth of afternoons. White lilies. A sun in the corner—childish, maybe, but the kind of childish that believed in radiance. She placed the note under the vase and walked away. The quickness in her chest felt like stealing and confession at once.

When David arrived, he stopped so abruptly one lily lost a petal midair. The drawing could have been Isabella’s. Not her exact lines—no one could mimic the particular way she looped a stem—but the same stubborn cheerfulness. He touched the edge of the paper as if it might burn him. He looked a long time at the sun. He looked around, saw no one, and for the first time in a calendar of sorrows the corners of his mouth lifted. It wasn’t joy, not yet. It was the memory of how to make the shape of joy.

There were more drawings after that. Butterflies fat with color, blue rain that watered green grass, a rainbow arcing over the stone like a promise he couldn’t afford but still wanted to buy. Each signed with nothing more than a heart and the letters E M—tight, careful, like stitches. David began bringing two bundles of lilies. One he arranged for his daughter. The other he left for the artist whose kindness made the air less barren. He wrote short notes: Your kindness means more than you know. Or: The world feels less cold when you color it. Or simply: Thank you.

On a morning that arrived with ordinary sunlight, the small hinge of things turned. When David set the lilies down he heard a wisp of sound behind him—not a footstep, exactly, more like the sound a page makes when a reader reaches its end. He turned and saw her. Long brown hair and a notebook held like a shield. She stopped moving and looked ready to sprint, a deer about to choose a path between two trees.

“You’re the one,” he said. His voice failed and came back. Softer. “You’ve been leaving the drawings.”

“I didn’t mean to intrude,” she stammered. “I just—” She swallowed, and when she spoke again she felt something calm click into place, as if the words had been waiting to enter the room. “I just didn’t want her to be forgotten.”

The line of his mouth trembled, then steadied. He passed a hand over his chest, as if confirming that his heart had stayed where it belonged. “Thank you,” he whispered. It sounded like prayer. It sounded like breath returning to a drowning man.

They sat at the base of the stone. The grass made their palms green. Elena told him about the dozen kitchens she’d learned to navigate without making noise, about teachers whose pity came packaged as extra forms to sign, about art as a door she could open even when the house itself was locked. David told her about Isabella; he shaded in the details so precisely Elena could see the girl laughing, could smell strawberry shampoo, could hear the small breath she took before she blew on a drawing to dry the marker streaks.

They spoke long enough for the sunlight to swing sides. When at last they stood, the day had the exhausted sweetness of a fair winding down. “I come every Sunday,” David said. “If you want… if it’s safe for you… we could—” He didn’t finish the sentence. He was a man who had learned how sentences can become promises and promises can become ruins.

She nodded. “I’ll come,” she said.

She did. The next Sunday, and the next after that. David stopped bringing lilies and started bringing paints and sketchpads that smelled like bookstores and possibility. Elena opened the kit as a pilgrim might open a reliquary. They painted side by side, giving Isabella a meadow, then a sky, then a city bright as parade balloons. David’s hands remembered how to make things whole. He repaired a broken wooden bench by the oak tree and fixed its wobble, the act as tender as a caress. Elena noticed that when he laughed, he always looked to the side first, as if asking permission from an empty space beside him. She answered the empty space in her own way—by laughing louder, to make sure the joy reached whatever previous silence he feared.

The cemetery groundskeeper, a man with a coffee mug that said WORLD’S OKAYEST GARDENER, began to wave at them. Sometimes he left them pastries wrapped in napkins. Community gathered around their grief until the grief had edges that no longer sliced their hands.

But walls remained. David carried a house full of ghosts. Elena carried a house that was not hers. The present was a bridge they were still learning to walk without looking down. On one of those afternoons, thunder stitched along the horizon as if the sky were relearning how to be broken. Elena stared at the dark line in the distance and said, too casually, “Storms make people mean.”

“Not always,” David answered, and then saw her face tighten and realized she wasn’t looking for debate. “But sometimes. Yes.”

In her current foster placement, the father was a man who liked crisp silence and conservative television; the mother was a woman who apologized for the permanence of the drapes. Neither was cruel, not exactly. But kindness seemed to be something they had filed away under a legal document and never took out again. Elena clocked their moods with the precision of a sailor watching barometers. She kept her grades perfect because perfection was a language that even distant people understood. She kept her backpack organized because she was ready to move.

Yet in the coiled wire inside her, a warmth spread. David started teaching her small repairs: how to reset a tripped breaker, how to find a leak by listening for it instead of looking. The first time she used a torque wrench, she felt the world answer her with a satisfying click—resistance measured, balance restored. Work, she realized, was another language for prayer.

They began to share more than Sundays. After the cemetery, they went to his shop. The sign above the door read Romero Repairs—faded, honest. Inside, the air carried the musk of oil and wood dust. In one corner, a table spread with paints like a confession: a new life taking shape where old lives had either stopped or been mended.

“Everyone thinks repair is about making things look like they did before,” David said one evening, setting a broken music box on the bench. “But it’s not. You can’t go back. Repair is about making something work again. Sometimes you even find a better tune.”

Elena watched his fingers find the minuscule pin that had shaken loose. When the lid finally opened and the ballerina spun—wobbly at first, then certain—Elena felt an ache under her ribs. “Better tune,” she whispered, as if testing the idea.

When she left that night, a neighbor saw her step out of the shop and told someone who told someone else. Narratives crook quickly in small towns. By the time the rumor reached Elena’s foster parents, the story had become untidy. A concerned caseworker knocked, eyebrows raised like quotation marks. Elena’s stomach went ice-calm, the way it always did before she decided which truth would keep her safest.

“Mr. Romero,” the caseworker said when they met, “is he… appropriate?”

Elena watched David’s hands twist at the hem of his shirt as if trying to wring water from memory. She wanted to speak loud enough for the world to hear. She wanted to say that he placed paintbrushes in her palm the way one places candles in a church—carefully, reverently. Instead she let the caseworker’s questions ripple through a labyrinth of protocol and answered each one precisely, fact for fact, until even suspicion bored itself to sleep.

“Appropriate,” she said afterward, laughing with her breath still shaky. “I feel like I’ve been stamped by a machine.”

“Machines don’t get the last word,” David said. “Not if we can help it.”

They returned to the cemetery the following Sunday with jasmine tea in paper cups. The oak threw dappled light across the headstone, making the carved letters breathe. Elena set down a new illustration: Isabella with a paint-splattered smock, reaching toward a vast sky with a brush. The sky was half blue, half blank space, as if inviting completion.

“Will Maria ever come back?” Elena asked, then instantly regretted the nakedness of the question.

David rubbed his thumb across the cup rim. “We talk sometimes. She’s in San Marcos. She’s found a quiet street, a job making cakes that are too beautiful to eat. We aren’t enemies.” He paused, measuring the words against the world. “Grief makes you grow in different directions. Sometimes you can’t bend back.”

Elena nodded, filing the sentence in the cabinet she kept for sentences that could hold weight. “Different directions,” she repeated.

She didn’t say the sentence she thought next: that maybe families were maps, and sometimes the roads you needed were the ones drawn in later by hand.

Part II

By fall, the groundskeeper’s mug broke—irony—and David fixed it with a clear resin that taught the crack to shine. “Kintsugi,” he told Elena, explaining the Japanese art of repairing with gold, making flaws glow. “I don’t have gold. But I have patience.”

“You have both,” Elena said.

Patience learned the timetables of a high school senior year: applications, scholarships, essays that demanded a biography when all she had was a stack of unflattering addresses. She wrote anyway. She wrote about drawing as a way to keep light obedient, about repairing as a way to respect what had once been whole. She wrote the truth about Isabella—not the details that belonged to a family, but the way a stranger’s grave could become an altar where the living remembered how to be alive.

David read drafts at the shop counter after closing, red pen hovering. He circled phrases not to scold them, but to polish them. “You don’t need my approval,” he would say, handing the paper back. “But you have it.”

When an acceptance letter arrived from a community college with a good art program, Elena sat on the curb outside the mailbox with the envelope in her lap and breathed until breathing became something she could trust. It wasn’t a prestigious university with gothic towers. It was a room with windows. It was a door that opened. She brought the letter to the grave. They pressed it together against the cool stone as if inviting Isabella to sign it.

“Can you afford it?” David asked gently.

“Scholarship covers seventy percent,” she said. “The rest is the kind of math that keeps you humble.”

He did his own math silently and then set it aside. “Come by the shop after school. I’ll teach you the register. We can look for extra shifts.”

She did. She worked three afternoons a week, the bell above the door teaching her the choreography of neighbors. She became fluent in the way people asked for help without asking. A widow brought a mixer whose beaters no longer turned; Elena repaired the gear and listened to stories of cakes baked for a marriage that had lasted fifty years and a day. A teenager brought a skateboard with a stripped bolt; Elena replaced it, then taught him how to do the job himself next time. David watched these transactions with a stillness that hid joy like a coin in a pocket.

In November, Maria returned to town for the first time since she left, not to stay but to deliver a cake to a cousin’s baby shower. She parked by the cemetery and sat in her car with the engine off, hands at noon and three as if she were still being judged by a driving instructor. She considered leaving. She considered accelerating. Instead she walked the path under the cypress and saw two figures at the grave: her husband and a girl she did not know, both painting as if the air gave instructions.

Elena was the first to see her. Elena rose, uncertainty making her spine too straight. David looked up and felt the old geography shift under his feet.

“Maria,” he said. No question, just a name ripened by silence.

“I didn’t want to interrupt,” she said. But the word interrupt carried a dozen meanings: I didn’t want to reopen what won’t close. I didn’t want to become an element in your equation. I didn’t want to see you happy or unhappy or anything that I couldn’t measure from a distance.

“This is Elena,” David said. “She’s—” He glanced at the painting, at the bench, at the cups of tea, at the stack of drawings wrapped with a rubber band. The language that came next surprised him in its clarity. “She’s become family.”

Maria’s eyes filled quickly, then steadied. She stepped closer to the stone. “Hello, Isabella,” she whispered, and the air bent to make space for the sound. She touched the edge of Elena’s painting—a sky half complete—then looked at the girl with the careful posture. “You drew this?”

Elena nodded.

“It’s beautiful,” Maria said. She said it with the kind of sincerity that refuses to overreach.

They didn’t talk long. They didn’t need to. Shared silence did the work. Before she left, Maria touched David’s arm—an old reflex, kind, uncomplicated. “I’m glad you’re… making things work again,” she said. She looked as if she wanted to choose a better phrase, but that one would do. Repair. It was their common language, even now.

Elena watched her go, a figure shrinking along the path that had carved itself into memory. “She has your steadiness,” Elena said.

David chuckled. “She’d say I stole mine from her.”

December came with a thin frost that powdered the grass and made every step careful. On an evening the color of pewter, Elena’s foster father came home early and slammed a cupboard hard enough to chip its paint. Elena swept the shards into her palm before they could be counted against her. At dinner he said grace with a voice thick as gravy and then complained the potatoes were underseasoned. “Ungrateful,” he muttered to no one, to everyone. Later, in the living room, he turned the television loudly toward a show where men bought storage units and barked at each other. Elena went to her room and closed the door. She drew a bowl of potatoes and seasoned them with stars.

At the shop the next day, David noticed a new bruise near her elbow. She explained it away with the finesse of the well-practiced. He didn’t press. He handed her a small screwdriver and a toaster with a failing spring. “Things that pop back up after heat,” he said.

“Wish they all did,” she answered, and the smile they shared made the room feel wider.

On the Sunday before Christmas, the cemetery wore tinsel attempted by the wind; a neighbor had tied ribbons around several stones and the cypress had accepted the decoration with stoic grace. Elena brought a garland of paper cranes she had folded the night before while the television blared in the other room. Together, she and David draped it across the upper corners of the gravestone, the cranes’ wings lifting at the slightest breath.

He cleared his throat. “I got you something,” he said, and handed her a small box that had once held screws. Inside lay a key on a bright ribbon. “To the shop,” he added quickly. “Only if you want it. For when you need a place to sit with the lights on.”

The key was a small moon on her palm. “I want it,” she said, and the thanks in her voice contained a history that doors would someday understand.

On New Year’s Eve, the foster parents went to a church vigil. Elena told them she was too tired. She walked to the shop. She turned on the lights and watched them refill the windows. She made tea in a chipped blue mug and sat at the workbench with a sketchpad. When fireworks glimmered somewhere far away, she drew not the spark—but the smoke that lingered after, the quiet proof of something that had burned without burning the neighborhood down. She hung the drawing by the register like a flag.

By spring, the town learned their schedule: Sundays at the grave, afternoons at the shop. Someone organized a small art show at the library called Mending: New Works by a Young Artist. Elena mounted her drawings on foam board David salvaged from a packaging order. The library smelled like paper and dust sweetened by decades of stories. People came the way people come to baptisms and the opening day of a diner: to witness a beginning. The groundskeeper wore a tie as if attending a wedding. Maria sent flowers. The caseworker stood in the corner and tried not to look astonished by how ordinary good things can be when they’re allowed to happen.

In front of a drawing of a sky half painted, an older woman asked, “Why do you leave the rest blank?”

Elena considered. “Because sorrow is the part we can’t finish,” she said after a moment. “But we can paint around it until it points to something else.”

David watched her answer, proud and humbled by a sentence he knew he’d remember on nights when memory pressed hard. He thought of Isabella’s bedroom—how they’d left the drawings on the wall until the tape surrendered, how a square of sun still appeared each afternoon in the place where her bed had been. Blankness could be a shrine. But also an invitation.

After the show, a woman from the college offered Elena a part-time job in the campus studio—washing brushes, stretching canvas, the holy mechanics of art. The math of tuition shifted closer to solvable. Elena took the schedule home to the foster parents and laid it on the kitchen table like a truce, like a dare. Her foster mother scanned the paper, shrugged, then asked what was for dinner. Her foster father squinted as if work were a personal affront. “We’ll see,” he said.

Elena had grown used to that phrase. We’ll see was a trapdoor disguised as patience. She smiled anyway. “We will,” she said.

On a warm Sunday in May, thunderheads towered like ships in the distance. The cemetery smelled of cut grass and rain not yet fallen. David and Elena painted a field of sunflowers so bright the air felt saturated with their color. Elena dabbed a high-light near the core of one bloom and stepped back, surprised by how alive it looked.

“Teach me that,” David said. He always said it gladly. He had learned to be a beginner in the presence of something beautiful. He copied her stroke and missed the mark and laughed at his own imprecision.

They didn’t notice the two men who paused by the gate, watching. The first wore a baseball cap and the second carried a camera that made a tiny insect whine when it focused. One murmured, “Human interest,” and the other said, “Small-town miracle.” They approached with smiles that showed too many teeth.

“We run a channel,” the man with the cap said, and named it. “We share real stories. Uplifting stuff. We’d love to feature you. A grieving father finds hope with a foster teen who leaves art at his daughter’s grave? People need that.”

David’s shoulders stiffened, subtle as a barely audible chord struck beneath a melody. Elena felt herself shrink to the size of a headline. The camera clicked. The men seemed harmless, but their charm had the clatter of a cash register.

“I… don’t think so,” David said, polite but firm.

“Think of the awareness we could raise,” the cameraman added. “For kindness. For foster kids. For grief support. We’ll be sensitive.”

Elena looked at the grave as if expecting Isabella to advise her. The oak leaves made answer-light. She imagined her drawings thumbnailed in a grid, bundled with music soft enough to lull people into believing every story ends with a ribbon. She imagined comments posted like confetti and then swept into a bin. She imagined David’s face, private prayers made public.

“Thank you,” she said, quieter than she felt. “No.”

The men hesitated, recalibrated, then retreated. The camera clicked one last time, stealing the shape of them as they sat in refusal. When they were gone, David exhaled, long.

“We tell this story to the people who earn it,” Elena said.

He nodded. He looked at the sunflowers they’d painted and saw, not their crowning brightness, but the way they followed the sun in slow devotion—turning not because someone filmed them, but because that’s where the light lived.

Summer arrived with heat that flared off roofs and smudged the horizon. Elena turned seventeen. David made her a cake shaped like a paint palette, each blob of frosting a different color. Maria sent a card with a pressed flower inside; when Elena unfolded the note, the flower fell into her palm like a memory she didn’t own but was allowed to keep.

Elena’s foster father eyed the gifts with a mouth like a stapler. “Remember who feeds you,” he said, as if kindness were theft. The foster mother sighed and said they’d be happy when Elena found a dorm room and a dining plan. Elena nodded and loaded her backpack with practicality: a roll of painter’s tape, pliers, a flashlight, the key to the shop. The future didn’t scare her. It glittered with work.

Part III

The last summer Sunday before classes began, David arrived at the cemetery first and kneeled in the familiar pose. Words rose and fell. Some apologies decay slowly, like iron under rain; others release you suddenly with a click. He had learned to speak to Isabella out loud, not because he expected an answer, but because grief prefers language to silence when love is the speaker. “You’re still my morning,” he said. “Just… farther east.”

When Elena arrived, her backpack looked heavier than usual. She set it down and pulled from it a wooden frame she’d built from scrap pine. Inside stretched a canvas she’d primed the night before. “I thought we could paint one big thing,” she said. “Together.”

“What should it be?” he asked.

“Not a grave,” she said. “But not pretending there isn’t one.”

They began. David sketched a rough horizon with charcoal, a line that understood where earth stopped and sky began. Elena laid a wash of blue, leaving a central oval of bare canvas that could be either a wound or a halo. The oval looked wrong. She frowned. David smiled. “Keep going,” he said. “Wrong things are often beginnings.”

They layered color. Sunlight ran its hands through the leaves and flicked them onto the canvas. Birds diagrammed breath overhead. Hours slid by with the sweet utility of water washing dishes clean. A portrait emerged—not of a person, but of a meeting place: the oak tree in generous shade; the bench whose wobble had become a memory; a child’s handprint faint in the corner as if pressed there years ago, then discovered only now. The center oval—they decided—would stay unpainted. A place for what could not be filled, and for light to visit.

They stepped back. They didn’t speak. The painting didn’t end the story; it allowed the story to live.

A car door slammed somewhere beyond the gate. Elena flinched before she knew why. Old habits wore grooves. But it was only the groundskeeper, hat in hand, mug repaired with resin flashing a seam like a comet. He smiled and waved off their apologies for taking up space. “This is good work,” he said, looking at the painting not with a critic’s eye but with a neighbor’s heart. “You’re making the place remember differently.”

“Can we leave it here today?” Elena asked. “Just while we go to the shop to let it dry?”

“Of course,” he said. “I’ll keep an eye on it.”

At the shop they ate sandwiches over the register. David showed Elena how to replace a belt in a vacuum, how to meter electricity with a tester, how to hear the truth when a motor lied. “You’ll need these in the dorms,” he said. “You’ll be rich in friends if you can fix a microwave.”

“I’ll charge them in cookies,” she said. “It’s a fair economy.”

They returned to the cemetery near dusk. The oak made long fingers of shadow. On the bench sat a woman whose hair caught the light like fine thread. She wore a dress the color of early morning and had the composed expression of someone who had practiced despair until it no longer owned her face. Maria stood when she saw them and moved with purpose toward the painting. “I came to say goodbye,” she said. “And to say—no, to ask—if I could borrow part of your courage.”

They looked at her, not understanding.

“I’ve decided to move back,” she said. “Not to the marriage, not unless the marriage is something new. But to the town. To the grave. To… this. I can’t keep basting love onto cakes and pretending it’s enough.”

David felt the ground shift again, but differently—like a boat settling at a dock after a long drift. “There’s a small house for rent near the shop,” he said, surprising himself with his speed, with his desire to make a landing for her real. “We can ask the landlord to be patient. I can help with—”

“We can,” Elena said, stepping into the plural with a confidence that expanded the air.

They stood a moment, rearranging the furniture of the future. It wouldn’t be simple. They didn’t pretend it would. But simplicity was overrated; accuracy mattered more.

After Maria left to meet the landlord, Elena knelt by the stone. “Isabella,” she said, “I’m going to college next week. It feels like leaving and also like arriving. I know you would draw the dorm walls and make them bright. I’ll try.”

David crouched beside her, and their two shadows leaned long across the grass like one. “You gave me back Sundays,” he said.

“You gave me a door that opened,” she answered.

They sat until the sky trained itself on night. Before they left, Elena slipped the canvas under the bench, away from the dew. As they walked down the path, David realized he had not watched his feet for several steps. He was looking outward again.

The first week of college brought such wealth of new that Elena felt broke with it. Classrooms with windows and professors who said words like aperture and negative space as if they were utensils you could set on a table and eat with. A studio full of easels. A bulletin board where students advertised for bands that needed a bassist and for apartments that needed a third roommate. She taped David’s schedule in her drawer so she would know when he was at the shop in case the loneliness pressed too hard and she needed to hear the bell of the door and the everyday music of a cash register he’d tuned to sing slightly sharp.

She called him on Thursday. “They have a kiln,” she said, as if reporting a myth confirmed. “And a professor who broke a bowl on purpose to teach us how to mend the cracks with glaze.”

“Kintsugi,” he said.

“With gold,” she added. “Real gold. I thought of the gardener’s mug. He’d be proud.” They laughed. Then, softly: “How’s the grave?”

“Visited,” he said. “Lilies. The painting is safe. The groundskeeper watches it like it owes him money.”

“Good,” she said, releasing a breath she didn’t know she’d been holding.

Mid-September brought a storm that made gutters sing. On a Sunday morning rara with thunder, Elena took a bus from campus to town. She wore a jacket too thin for the weather and carried a portfolio under her arm. When she stepped off near the cemetery gate, the rain softened as if curious. She saw David kneeling, the familiar curve of his back, and something in her heart aligned, compass finding north.

She was halfway down the path when she saw the other figure—a man at the edge of the oak’s shade, hat tilted, camera hidden but not absent. The channel had come back with better stealth and worse intentions. Elena froze. David looked up, followed her gaze, and saw the man. The man lifted two fingers in a salute that pretended to be friendly and melted into the deeper trees.

“Do we tell someone?” Elena asked, anger staking a claim in her voice.

“We tell the right people,” David said. He felt not fear but a clean protective heat. They spoke to the groundskeeper, then to the library director who knew everyone’s business in the gentle way; by afternoon the town understood that some stories had boundary lines painted bright. The man with the camera tried again once more and found his way barred by bodies—neighbors drinking coffee under umbrellas as if the rain were an excuse to stand watch. He left. The air exhaled.

The semester rolled into a rhythm: early classes, studio time, shifts at the shop on Fridays, Sundays at the grave. Elena’s foster parents came to the art building once, walked through the halls with narrowed eyes, and left without a word. The caseworker called to say Elena’s file would need one last signature on her eighteenth birthday to mark the end of custody. “You’ll be free,” the woman said, with a hint of apology for the word.

“Freedom sounds like a room I’ll have to furnish,” Elena said. “I’m ready.”

“Do you know where you’ll live?”

“Yes,” Elena said. “With people who started as strangers and turned into directions.”

On the evening of her birthday, Maria baked a chocolate cake with a seam of raspberry in the middle and brought it to David’s kitchen, which had slowly become everyone’s kitchen. They ate slices on paper plates that sagged under the weight. David gave Elena a set of tools in a neatly rolled canvas bag. “Your own,” he said. “No more borrowing.”

Maria gave her a framed photograph—not of Isabella alone, but of the grave with the paper cranes, the bench, the oak. “Places can be family too,” she said.

Elena touched the frame and imagined packing it for every move she would ever make: dorm rooms, apartments with thin walls, someday a place she could choose not for its price but for its windows. “Thank you,” she said. The words were small. The gratitude was a sky.

After the plates and candles and laughter, the house settled. Rain ticked the windows. Maria washed dishes with the familiarity of old songs. David dried them, the towel moving with a choreography they’d practiced years ago when the world still had a bedtime story waiting. Elena stood in the doorway and watched them, the domestic rhythm as sacred as any hymn. She understood then—clear as a bell—that love doesn’t come only in one shape, one script. Sometimes it is a man drying plates and a woman making sure the cups are stacked with their handles aligned. Sometimes it is a father whose daughter is gone and a daughter who never had a father until she found one at a grave.

On the next Sunday, they brought the large canvas to the cemetery together. The groundskeeper had cleared a space on a nearby brick wall under the pavilion. He had hammered in two hooks himself, proud as if he’d carved the hooks from the tree. “This belongs here,” he said, and when they hung the painting, the oval of blankness at its center seemed to glow of its own accord.

David spoke aloud, voice steady. “Isabella, your friends are here. Your mother is here. I am here. We are… still here.” He wasn’t asking the universe for forgiveness anymore; he was giving the universe an accounting. He touched the bottom corner of the canvas and pressed his thumb, leaving a small print. Elena did the same. Maria too, after a second’s surprise, pressed her thumb softly where the paint had thickened into relief. Three prints. Not signatures, exactly. More like coordinates.

And there, at last, the story found its shape: a father weeping at his daughter’s grave, unaware at first that a girl was watching from under the oak, then learning to see her fully—with trust, with gratitude, with the kind of love that doesn’t replace but companions. The man’s grief didn’t vanish. The girl’s past didn’t rewrite itself with prettier ink. But kindness built a bridge sturdy enough for all of them to cross: from apology to purpose, from loneliness to connection, from a stone carved with endings to a canvas stubborn with beginnings.

They stayed until evening rounded the edges of the day. When they rose to go, a wind passed through the cypress, soft as a hand. The paper cranes shivered. The lilies resettled in their vase. Elena looked back once and imagined, not a ghost, but a presence—the way a room remembers laughter long after the guests have left. She lifted a hand and waved to the air.

“Goodnight, Isabella,” she said. “I’ll see you next Sunday.”

David took a breath that felt like a first breath after surfacing. He did not count the minutes since the accident anymore. He counted new things: canvases, repairs, shared dinners, the number of times laughter overlapped like chords in harmony. He took Maria’s arm as they walked and felt, not a return to the past, but a step into a future where the past did not need to be argued with. Elena walked beside them, keys in her pocket, her own steps strong.

Above the path the sky held its pose just long enough to be memorized and then—like all skies—changed. The oak watched them go. The painting stayed, catching the last light, its blank center welcoming not emptiness but arrival. And if—only if—you listened, you could hear the small bright sound of a child’s giggle threading the wind, not as a haunt, but as a blessing.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

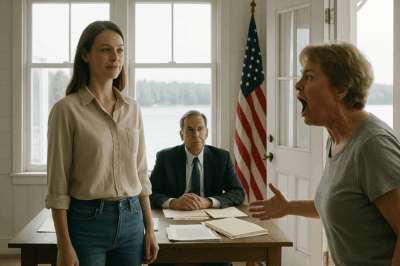

CH2. HOA Karen Busted Into My Lake Cabin — Didn’t Realize I Was Meeting the State Attorney General Inside

HOA Karen Busted Into My Lake Cabin — Didn’t Realize I Was Meeting the State Attorney General Inside Part…

CH2. “May I Take A Turn?—The SEALs Didn’t Expect The Visitor To Smash Their Longstanding Record

May I Take A Turn?—The SEALs Didn’t Expect The Visitor To Smash Their Longstanding Record Part I The sun…

CH2. Three Trainees Confronted Her in The Cafeteria — Moments Later, They Found Out She Was a Navy SEAL

Three Trainees Confronted Her in The Cafeteria — Moments Later, They Found Out She Was a Navy SEAL Part…

CH2. “You Can’t Enter Here!” — They Had No Clue This Woman Would Become Their Military Leader

“You Can’t Enter Here!” — They Had No Clue This Woman Would Become Their Military Leader Part I The…

CH2. “Wait, Who Is She?” — SEAL Commander Freezes When He Sees Her Tattoo At Bootcamp

“Wait, Who Is She?” — SEAL Commander Freezes When He Sees Her Tattoo At Bootcamp Part I — The…

CH2. Four Recruits Surrounded Her in the Mess Hall — 45 Seconds Later, They Realized She Was a Navy SEAL.

Four Recruits Surrounded Her in the Mess Hall — 45 Seconds Later, They Realized She Was a Navy SEAL …

End of content

No more pages to load