The Captain Said “Stay Out of This” — Then Watched Her End the Fight in One Move

Part I — Mess Hall Physics

It was the kind of noise that makes cutlery sound violent. Stainless steel on plastic. Boots on tile. Voices cracking like ice on a river trying to remember it was once solid. Evening chow in the mess hall was always loud, but that night the sound swelled with a pressure you could feel between your ribs.

They’d pushed two tables too close together. That was how it started. Two squads—Echo and Fox—had come in shoulder to shoulder and neither wanted to cede an inch of space or credit.

“I’m not saying you cheated,” Fox’s squad leader said, smiling the way men do before they hit, “I’m saying you wouldn’t know fair if it had a safety on.”

Echo’s corporal laughed without smiling. “We were in and out before you’d synced comms. That’s not cheating. That’s competence.”

“I heard competency isn’t contagious,” someone in the back said. “Good thing, because we’d be doomed training next to you.”

The temperature in the giant room dropped a fraction; the fluorescent hum sounded sudden and cruel. Someone mentioned someone else’s girlfriend. Someone countered with a story from a night out that had three versions and zero verifications. Forks turned into gestures. Gestures turned into fists.

Then someone threw the first punch.

It landed in a way that makes a room agree: yes, we are doing this. Chairs skidded. Trays flipped. Mashed potatoes slid under boots and became what you slip on when you forget to look down. The group behind the drink machine cheered like a crowd at a game they hadn’t planned on watching. A steel chair went over with a sound like a gunshot. Reflexes sharpened into weaponry.

At the corner table, away from the habitual currents of movement, Corporal Leah Grant stood, tucked her chair back under the table with the same precision she had used to fold her napkin, and took in the entire room with one sweep of her eyes.

She was twenty-nine. There was a fresh scuff on the toe of her right boot from a drill that morning where a private had forgotten to brake before running into her. She had transferred six months ago under a cloud labeled with bureaucratic language—disciplinary neutrality, pending review—after something went wrong in a place no one liked to say out loud. Her file lived behind a wall of redaction. Every rumor about her ended with “I don’t know” from someone who pretended they did.

“Enough!” Captain James Weller shouted as he jogged in from the hall, his voice pitched to that tone officers learn when they need words to carry weight over that of adrenaline. He had graying temples and eyes that had learned to count faster than most people live. “Stand down. That is a direct order.”

Momentum is Newtonian. Orders aren’t physics.

A Fox heavy caught an Echo private by the throat and pinned him against the cinderblock wall. His feet came off the floor. His hands clawed at the iron bands on his neck, his mouth opening and closing in silent outrage, then panic. The man squeezing was smiling—a round, generous, dangerous smile—at the way everyone shouted and no one moved.

“Grant, stay out of this!” Weller barked, spotting her as she took one deliberate step. “That’s a direct order. You’ll just make it worse.”

“Yes, sir,” Leah said. She paused. Her body was quiet in the way a cat is quiet before it leaps from a windowsill to a fence post half again its height.

The private’s face darkened. His heels drummed two frantic staccatos against tile. His fingers weakened.

Leah moved.

She didn’t run. She didn’t yell. She crossed the distance with the kind of economy that makes watchers think they missed frames. Her left hand rose, palm outward. She redirected the choke-hold elbow with a precision that made the joint forget what it had been intending to do. Her hip rotated one notch like a safe opening to a single number. The heavy lifted. For a brief, absolute second, he traced a clean arc in the air and the room held its breath for him.

He landed flat. The floor caught his back with the generosity of physics and drove air out of him in a sound that made five people’s hands go to their own ribs. He lay blinking at the stained ceiling, mouth opening and closing like a fish pulled from a river you’d swear was fine the last time you looked at it.

Silence snapped over the room. Even the fluorescent buzzing dimmed. Grease smell faded. Motion was suspended above each body like a question they hadn’t realized had been asked.

Leah’s hand returned to where it had been—behind her back. Her expression did not change. Neither did her heart rate.

“What the hell was that?” Weller said, not Captain now, just a man who had witnessed a magic trick he didn’t know was legal.

Leah turned. “Intervention completed, sir,” she said, voice level as a spirit level. “Threat neutralized. No permanent injuries.”

The man who’d been strangled slid down the wall and sucked in air he seemed to have forgotten belonged only to him. The medics shouldered through with workmanlike concern, checked pupils, cycled through concussion protocol, taped a wrist that did not need taping because care is sometimes performance too. No one tried to punch anyone else. A few privates stood very still and realized they were not, in fact, in charge of the story.

“I told you to stay out,” the captain said again, softer. He sounded like a man who’d just found a safe in his house he couldn’t remember installing.

“Understood,” Leah said. “The subject had approximately twenty to thirty seconds before hypoxic blackout. He would have fallen unconscious, dropped his full weight, and cracked his skull on tile. You’d have had a fatality before the word ‘contempt’ took shape in your mouth.”

Around the room, eyes flickered. Echoes of stories about her ticked into sync: rumor had it she’d been attached to a unit that didn’t exist, did things that never made it into a list people could clap for before dessert. A blacked-out rectangle on an org chart above a note that simply said, command black. Someone swore they’d seen a citation in a file that closed itself at the edges when opened. Someone else said anyone who taught herself that kind of quiet had probably already decided who was worth making noise over.

Back in his office, Weller watched the footage twice at one-tenth speed. Master Sergeant Rodriguez stood behind him, arms crossed, jaw hard.

“Not basic,” Weller said.

“Not Ranger,” Rodriguez said. “Not even anything we’d let the Rangers borrow if they asked nicely. That’s level five restraint.”

Weller leaned back. Old leather sighed. “We told that skill to stay out.”

“We ordered a scalpel not to cut when an artery had been nicked,” Rodriguez said. “Good thing it didn’t listen.”

Part II — Aftermath

At 0700, Corporal Leah Grant stood at attention in Captain Weller’s office. The office was what men of Weller’s generation thought made them look like men of their father’s: wood paneling, photos with creases, a shelf full of gifts no one would dust after his retirement. He didn’t sit. He tapped a knuckle against the desk, once, like he was trying to find out if it was hollow.

“You disobeyed a direct order,” he said. “I told you explicitly to stay out.”

“Respectfully, sir,” Leah replied. “I prevented a death. Loss of consciousness in partial strangulation can occur within fifteen to thirty seconds. Anoxic brain injury begins at approximately four minutes. The subject would have dropped the other subject and cracked his skull. Likely intracranial bleed. Worse if he hit the corner of the table. I did not have four minutes.”

Silence existed. Weller considered it and found it useful.

“Where did you learn that?” he asked. “What unit?”

Her gaze measured a slice of air somewhere between two picture frames. “Prior to reassignment,” she said, “detached to Shadow Team under Command Black.”

He let a breath out through his nose like a man who had found a locked room and discovered the key was in his pocket, fragile and hot. Command Black was a rumor the way gravity is a rumor; you can pretend you don’t know what holds the house down but the dishes stay on shelves anyway. He knew better than to ask for a file. Files like that do not come to men with his stripe; they visit them only to take away questions.

“You saw it escalating yesterday,” he said. “You knew it was coming.”

“Yes, sir.”

“You could have stopped it before it started.”

“Yes, sir,” she said. “But sometimes people need to see edges before they respect them. They need to smell the drop. They hear lectures. They don’t learn. That’s not on them. That’s on who taught them.”

He nodded because something in his sternum had moved. “Dismissed,” he said automatically, then caught her just before she crossed the threshold. “Grant.”

She turned.

“I’m reassigning you,” he said. “Effective immediately—combat training instructor. If you’re going to disobey orders to save lives, you may as well be paid to teach others why you did.”

Her mouth flicked into the idea of a smile, then disciplined it. “Yes, sir.”

By 1400, the base gym smelled like rubber and ambition. Weller cut through the usual pattern: run, sweat, laugh, fake punch, flex to amuse each other. “Corporal Grant,” he called, “front and center.”

Two volunteers stepped forward with the showmanship of men who only knew a trick until they saw the card already in the pocket. Three seconds later both were pinned in joint locks that did not hurt and could not be escaped without giving permission.

“Get up,” she said, and released.

They stood, adjusting sleeves, rubbing wrists. Her voice carried to the rafters without effort.

“You don’t fight to win,” she said. “You fight to stop loss. Control is not conquest. It’s choices. This—” She shifted, and a private who couldn’t stop himself from laughing suddenly found the laugh replaced by confusion as he realized she had, without touching him, used his own shoulders to suggest both a bow and a lesson. “—is an end to force. Not the beginning. You train for when orders arrive too late or never get given at all.”

No one checked their phone. No one made the face people make when they are being told something because someone had a meeting. Weller stood at the back with his arms crossed and felt his job loosen its grip on his throat for the first time in months.

That night, someone taped a note to Leah’s locker: One move. One message. Respect. No signature. Block letters. Black marker. She looked at it for three seconds longer than necessary, then folded it and put it in the left pocket of her bag, the one with the hole she’d stopped mending just to remember there had been a year where she had mended nothing. She didn’t put the note in a personal effects box because she did not have one. She lived out of a ruck the way people who expect to move on do. She did not expect anything.

A week later, Weller crossed her path outside the training facility. He had a coffee he’d forgotten to drink. “You were right,” he said. “Prevention before intervention.”

“It’s timing,” she answered. “Only timing. Knowing when to step in and when to wait. Most people do the wrong thing on time or the right thing too late. You do the right thing in the only time there is.”

He shook his head and wondered whether he had spat those words at anyone else lately and had them bounce off.

Part III — Orders

There had been a disaster in a place no one would say aloud. They blamed Leah because it was easier to blame a vector than a system. They needed a scapegoat. She had broad shoulders. She took the write-up. She took the transfer. She took the silence. She didn’t take the guilt. It wasn’t hers to carry. She had returned to base life like a woman who had learned how to fold herself into small rooms. But small rooms could not hold what she knew.

Three weeks after the mess hall, a visiting brass paid a tour to the base and asked for a demonstration. He had the posture of a man who called other people’s posture poor. He watched Leah put two men down without breaking a sweat. His comment was a joke he thought would play: “Useful on a dance floor.”

She turned. “Useful in hallways where romances go bad,” she said. “Useful in domestic spillovers at gates. Useful in rooms where people think the right to an order gives them the right to take a life. Useful. Sir.”

Weller didn’t smile. He didn’t need to. His approval felt audible. The brass cleared his throat and moved on to the shooting range where metrics are easier to applaud because they involve holes in paper and not the chastening of egos.

The story of the mess hall made its way off base not as gossip but as doctrine: there had been an incident; there had been an order; there had been a moment when not obeying the order served the aim of the order better than obeying would have. In the next cycle, a quote appeared above the gym door. Hand-lettered. Clean. Stay out of this unless you’re here. Underlined. Signed by the captain. A small line below it read, Control, don’t conquer. No one admitted whose handwriting it was. Everyone knew.

Part IV — Finish

At dawn six Sundays later, nine recruits met Leah under the bleachers for an extra session. They had requested it, haltingly, embarrassed by their own request for help. She taught them how to de-escalate three different situations without moving their feet, then how to move their feet without anyone seeing them move. She told them one story, the one about the mess hall, then another, the one she never tells fully, about a street in a place with no street names where knowing when not to shoot has more honor in it than powder. She didn’t use adjectives. She didn’t have to. They listened like people who knew they were being told about something more important than technique.

At the end, the smallest of the nine, a woman with hair too short to curl and freckles that refused to be disciplined, stepped forward. “I panicked last month,” she said. “When two men squared off, all I could think of was my voice. It wouldn’t come out of my throat. I cried after. I was embarrassed. But tonight, when PVT Hale grabbed PVT Omondi, I told myself to look at elbows. You say elbows tell truths fists lie about. I intervened. It worked.”

Leah nodded. “Your voice doesn’t live in your mouth,” she said. “It lives in how you move. Use it there.”

The sun found the horizon. The base woke. The mess hall clattered. Echo and Fox ate at different tables for a while after that. Then one day they ate at the same table and no one said anything and nothing happened, and that was the measure of progress.

Weller wrote a letter he never sent. It started, In my time as commanding officer, I have made three mistakes of magnitude. He tore it up, because letters aren’t how he fixes things. He walked to the gym instead and watched the class for ten minutes and then walked to the base commander’s office and argued for budget to expand the program. He got it because sometimes arguing is easier when you finally know exactly what it is you’re arguing for.

Six months after the mess hall, a visiting congressional delegation stopped by on their tour of “our brave men and women” and a staffer in an expensive suit asked Leah what she wanted them to know about her work. She said, “That it’s boring the way hearts are boring. They mostly pump in regular rhythm. That’s why you are alive to forget about them.”

The staffer wrote it down and did not understand it until he thought about it later, in his expensive hotel, and realized why he hadn’t slept well.

Late one night, after the gym had emptied and the lights had done the thing they do when they decide they don’t need you, Leah knelt to clean the mats. She pushed a bucket, wrung a mop, and hummed the way she does when no one is around to tell her to stop. The mop made patterns in the drying water. Footsteps approached. She didn’t look up.

“Need a hand?” Weller asked.

“I have two,” she said.

He paused. “You all right?”

“I am,” she said. “I will be.”

He left because he finally understood that leaving is sometimes what’s called for. He turned the light off when he did and learned this: when the dark came down, Leah’s silhouette didn’t diminish. It held its size.

At reveille the next morning, two privates whispering in bunks repeated the legend with minor inaccuracies and major reverence: “She ended the fight with one move.” “The captain told her to stay out.” “He made her an instructor the next day.” “She used to be with Shadow Team.” “She was special.”

She wasn’t special. She was trained. She was disciplined. She respected timing. She knew which orders served the mission and which served fear. She had learned to honor the first without being snared by the second. She had also learned where to put chairs under tables so rooms look better after you leave them than when you entered.

Near the gym door, the sign remained. Stay out of this unless you’re here. Control, don’t conquer.

The base lived around it. Laughter picked up its rhythm again. Mashed potatoes still slid under boots on bad days. People learned elbows. Privates stopped crying because voices came when they lived in bodies first.

Leah ate in the corner when she wanted to. People left her alone because they had learned the right kind of respect and because awe is not a workable condiment. She put the note back into her pocket some mornings and touched it before she taught and then put it back without reading it because memorizing is for doctrine and she had work to do.

The captain passed her in the corridor and nodded. “Lesson learned,” he said. “Thank you.”

She nodded back. “Timing,” she said, not as a correction but as a reminder.

What had started in the mess hall ended where most things worth learning end: in a place where shouting had become silence because someone knew when to act. That was the one move. Ending the fight, not winning it.

The rest was just training.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. My Mom Screamed: “Where Do We Sleep?!” When I Refused to Let My Brother’s Family Move In My Home

My Mom Screamed: “Where Do We Sleep?!” When I Refused to Let My Brother’s Family Move In My Home …

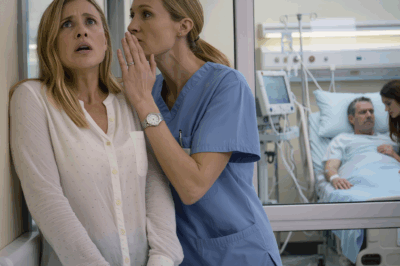

CH2. I Rushed To The ICU For My Husband. A Nurse Stopped Me: “Hide, Wait.” I Froze When I Realized Why…

I Rushed To The ICU For My Husband. A Nurse Stopped Me: “Hide, Wait.” I Froze When I Realized Why……

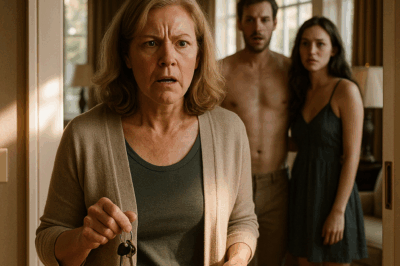

CH2. I Visited My Second Home To Rent It Out And Found My Son-In-Law There With His Mistress

I Visited My Second Home To Rent It Out And Found My Son-In-Law There With His Mistress Part 1 The…

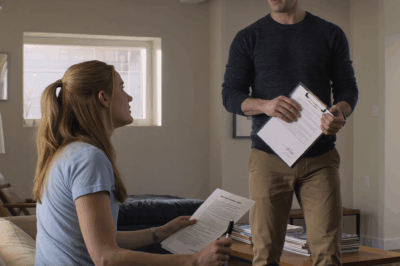

CH2. My Girlfriend Admitted: ‘I Faked Your Signature to Co-Sign a Car Loan for My Brother. You Can Handle the Cost.’ I Responded: ‘I Understand.’

My Girlfriend Admitted: “I Faked Your Signature to Co-Sign a Car Loan for My Brother. You Can Handle the Cost.”…

CH2. My Mom Changed the Locks and Told Me I Had No Home — So I Took Half the House Legally.

My Mom Changed the Locks and Told Me I Had No Home — So I Took Half the House Legally….

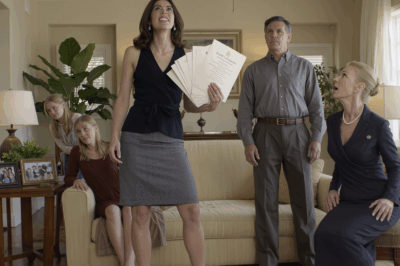

CH2. My Mom Said: ‘Stanford Is for Chelsea, Not You’ — So I Brought Out the Proof in Front of Them…

My Mom Said: ‘Stanford Is for Chelsea, Not You’ — So I Brought Out the Proof in Front of Them……

End of content

No more pages to load