The 9 Minutes Haguro Never Got Back — When One Missed Warning Triggered the Entire Ambush

It starts with a pulse.

A rhythmic electronic heartbeat sweeping across a circular glass screen in the dark.

It is just past midnight on May 16th, 1945, in the narrow gut of the Malacca Strait. Outside the bridge windows of the British destroyer HMS Saumarez, the world is a black, roaring void. There is no moon. Heavy rain squalls march across the sea in gray walls, hammering the surface, erasing the horizon.

Out there, human eyes are blind.

In here, the war looks like a green phosphor map.

The operator on the Type 293 radar set sits hunched over the scope, headphones clamped over his ears, the dim glow painting his face ghostly. The sweep line rotates, again and again, washing over the circular screen. It glows. It fades.

Nothing.

Just the constant shuffle of sea return, the low mutter of rain echoing on the receiver. A clutter of tiny imperfections.

Then, at bearing 340, something changes.

A blip.

Not a smear from waves. Not a fleeting spark. A solid, unmoving imperfection, persistent and bright.

“Contact,” the radar operator says, voice tight. “Bearing three-four-zero. Range sixty-eight thousand yards. That’s… thirty-four nautical miles.”

On the other side of the bridge, Captain Manley Power straightens. He is forty-four years old, lean-faced, with the tired eyes of a man who has been hunting a long time. His destroyer, Saumarez, leads the 26th Destroyer Flotilla—five sleek killers sliding through the night at his command.

He steps closer to the glowing scope, listening as the operator repeats the range, the bearing.

The contact is large. The return is too strong for a stray coaster or fishing junk. It is moving fast—twenty knots or more. And it is exactly where intelligence said a Japanese heavy cruiser would be.

Power does not guess.

He does not hope.

He calculates.

Range. Speed. Bearing. Time to intercept.

He turns to the plot table, where a yeoman is already marking the new contact—a small grease-pencil cross on a grid of lines, strings showing the positions of Saumarez and her four consorts: Verulam, Venus, Vigilant, and Virago.

“Signal the flotilla,” Power says quietly, picking up the Tannoy microphone. “We have our target.”

His voice crackles out to the others, four dark silhouettes cutting the sea miles away. He gives them a course. He gives them a speed. He begins to arrange his ships like pieces on a chessboard.

What no one on any British bridge can see is the way that single electron pulse—the tiny blip on the radar scope—has already killed an Imperial Japanese Navy cruiser that knows nothing about it.

Not the torpedoes that will come later. Not the shells.

This is the killing moment.

Because somewhere out there in the rain-soaked dark, a ship is sailing blind, fighting a 1942 war in a 1945 reality.

Thirty-four miles away, the heavy cruiser Haguro slices through the black water at twenty knots, her black hull shouldering aside the waves like a bull through tall grass.

She is a predator out of another age.

Thirteen thousand tons of hardened steel. Ten 8-inch naval guns mounted in five twin turrets. Twenty-four Type 93 “Long Lance” torpedoes slumbering in their tubes—oxygen-fueled, deadly, the finest underwater weapons of the war.

Her decks have seen more than most ships still afloat.

She has fought in the Java Sea, hunted Allied cruisers, survived the inferno of Leyte Gulf. Her logbook is written in smoke and salt, in the abrupt silence that follows a ship going under.

Tonight, her bridge is quiet in that particular way that belongs to warships at night—no shouted conversations, just low voices and the gentle clank of equipment.

On the open decks, dozens of men stand at their posts. They grip heavy binoculars, eyes pressed so long to the rubber eyecups that the skin is raw and tender. These are the fabled Japanese lookouts, men trained to see silhouettes in starlight, men who can spot the fragile line of a periscope at 5,000 yards. They are the product of years of doctrine that says human eyes will always matter more than machines.

They stare into rain and darkness.

They see nothing.

They do not know that a pencil-thin radar beam has just bounced off their hull, raced back across the night, and painted their position as a glowing dot on a British screen.

They do not know that their course and speed have been converted into mathematical coordinates on a plotting table in the bridge of HMS Saumarez.

Out here, the sea feels empty.

On that British bridge, it is very clear that it is not.

This is the paradox of 1945.

Haguro is the superior fighting ship—bigger guns, thicker armor, more men, more tonnage, more history. In a clear daylight gun duel, she would crush five British destroyers in minutes—her salvoes reaching farther, hitting harder, tearing their thin hulls apart.

But she is fighting the wrong kind of war.

On Haguro, the danger is theoretical, a phantom in the rain. On Saumarez, the target is a fact, plotted in grease pencil and confirmed with every sweep of the radar.

For the next hour, the distance will close. The British destroyers will separate and fan out, moving into a formation designed to exploit this exact blindness. They are not charging in like heroes from a painting, bows raised in a gallant line.

They are positioning themselves to execute a geometric sentence of death.

And the Haguro keeps sailing straight, unaware that the clock has already started running down.

To understand why Haguro is about to die, you have to look at her deck.

On paper, she is a Miyoko-class heavy cruiser, commissioned in 1929, modernized in 1936, built for one purpose: to destroy enemy shipping in surface combat. Her designers imagined her at thirty-plus knots, guns barking, torpedoes launching in glittering spreads at midnight across the China Sea.

She carries ten 8-inch guns—each one capable of hurling a 260-pound shell over twenty miles—and 24 Long Lance torpedoes that can slide through the sea like steel ghosts. Her crew of around 1,200 men are veterans of a long, brutal war.

But tonight, Haguro is not fighting as a warship.

She is fighting as a mule.

By May 1945, the Japanese Empire is starving. The once-sprawling merchant marine is mostly at the bottom of the ocean, devoured by submarines and aircraft. Oil no longer flows freely. Rice and ammunition no longer move easily from one island garrison to another.

So the Imperial Navy has begun using its surviving heavy units—cruisers and even battleships—as transport ships.

Haguro is steaming to the Andaman Islands on a relief mission.

Her beautiful teak-lined decks, once kept clear for action, are cluttered now with stacked wooden crates, lashed-down barrels, canvas sacks of rice, bundles of rope, fuel drums, all lashed and chocked where there used to be bare planks and swift feet.

It is more than an aesthetic crime.

In a naval gunfight, fire is the enemy. Steel can survive a hit. A clean deck means a shell that punches through might start a brief blaze, one that can be fought with hoses and sand and discipline. A cluttered deck means a single shell sprays splinters and shrapnel into wood and fabric and cardboard and fuel.

One hit becomes a bonfire.

The cargo also restricts the traverse of some turrets. If the enemy attacks from a sharp angle, turrets three and four may not be able to swing fully to bear without their barrels chewing into mountains of crates.

The ship’s physical geometry has been compromised by its logistical burden.

And then there is Haguro’s consort.

Sailing nearby is the destroyer Kamikaze. The name conjures visions of suicidal pilots diving into ships, but this is no kamikaze weapon. It is a real ship—an old destroyer, built in the early 1920s when the world still believed in Washington Naval Treaties and limited war.

She is tired, slower than modern destroyers, short on modern electronics and fire control. Her guns are small compared to Haguro’s. In a serious fight, she is more a liability than an asset.

Vice Admiral Shintarō Hashimoto, commander of this tiny task force, knows all of this.

His orders from Singapore are explicit and sobering:

Avoid engagement.

Deliver the supplies.

Return Haguro safely.

The Imperial Navy has barely a dozen operational heavy cruisers left. They cannot afford to trade one for a handful of British destroyers. Every heavy hull lost is a wound that will never heal.

That single fact shapes everything about Hashimoto’s mindset.

He is not hunting. He is preserving.

When you are hunting, every contact is an opportunity. You move toward the enemy, eager to close, to strike.

When you are preserving, every contact is a threat. You move away.

Your OODA loop—observe, orient, decide, act—is biased toward hesitation. You waste precious seconds trying to convince yourself a shadow is just a raincloud. You want the ocean to be empty. You want that indistinct shape on the horizon to be a fishing boat, not a destroyer.

You want to be alone.

Opposing him, on Saumarez, Captain Manley Power’s mindset is the mirror opposite.

He commands modern S- and V-class destroyers: Saumarez, Verulam, Venus, Vigilant, and Virago. These are not glamorous capital ships. They are, however, purpose-built killers.

Thirty-six knots flat out. Quick to turn, quick to accelerate.

They are empty of cargo and passengers, carrying only fuel, ammunition, and the men whose job it is to turn that into violence.

They have radar.

They have updated torpedoes—British Mark IXs, deadly in their own right.

Power has already given his captains a simple priority: ignore Kamikaze unless she interferes.

The destroyer is a distraction. The heavy cruiser is the prize.

The environment favors him.

The Malacca Strait is not some wide, open ocean like the Central Pacific. It is narrow and shallow, flanked by jungle-clad coasts, pocked with shoals and small islands. Navigation is tricky. Margin for error is small.

Tonight, storms complicate everything. Heavy rain squalls sweep the strait from the southwest, walls of water and wind.

For Japanese lookouts, the squalls are an enemy as vicious as any destroyer. They turn the horizon into a curtain. Even the best eyes cannot see through solid rain.

For British radar, the squalls are just noise.

The radar waves punch through, bounce off Haguro’s steel flanks, and race back to the aerials on Saumarez and her sisters. The operators adjust gain, filter out the clutter, and keep the target locked.

The ocean is becoming two different battlefields—one for men who rely on light, and one for men who trust electrons.

On Haguro, the night is still empty.

On Saumarez, it is filling up.

Half past midnight.

The gap closes at a combined speed of forty-five knots, nearly fifty miles an hour. Haguro steams northwest. She believes herself alone. Hashimoto thinks his recent course alterations have confused any submarines that might have been trailing him.

He has no idea a radar operator has been calmly watching his position update every few seconds without effort.

On the British flagship, Power splits his force.

He sends Saumarez and Verulam to Haguro’s port side to swing wide, race ahead, and cut off any escape route to the north.

To starboard, he detaches Venus, Vigilant, and Virago, ordering them to drop back, guarding the rear and eastern flank.

On the plotting table, the drawing takes shape.

Haguro is a central point. The British destroyers are spreading out into a five-pointed pattern around her.

They are building a box in the water. A torpedo box.

If Haguro keeps going straight, she will sail into a crossed field of fire from both wings.

If she turns left, she runs toward Saumarez and Verulam.

If she turns right, she runs toward Venus and her sisters.

There is no truly safe way out—if she knew the box existed.

But she doesn’t.

For the British, it is a bold and dangerous maneuver. They are violating a cardinal rule of warfare: never divide your force in the face of a superior enemy.

If Haguro detects one wing early, she can bring her 8-inch broadsides to bear and cripple it before the other wing can close.

Success depends entirely on one fragile condition: invisibility.

On Saumarez’s bridge, tension grows thick.

The deck trembles with the vibration of engines pushing toward thirty knots. Spray smashes against the bow, flinging itself in luminous arcs, phosphorescence glowing in the disturbed water.

Every man is acutely aware that if Haguro spots them now at ten miles and opens fire, they will be destroyed before they can even think about torpedo range.

They have to walk into the lion’s den without waking the lion.

“Range, twelve thousand yards,” the radar operator calls. “Eleven. Ten.”

On the green screen, the blip is swelling, constant bearing, range closing.

On Haguro, the Japanese face their own kind of nightmare.

The ship likely has a Type 22 surface-search radar, the best the Imperial Navy could manage under wartime constraints and bombing raids on its industry. But Japanese radar technology in 1945 has a crippling flaw: it struggles to filter out reflections from nearby land and heavy seas.

Here in the Malacca Strait, close to coasts and islands, with rain squalls everywhere, the Type 22’s display is chaos.

The Haguro’s radar operators stare at a scope filled with ghost signals, clutter, smears that might be echoes from waves, islands, rain, or some enemy that might or might not be there.

Their confidence in the machine is limited.

Their confidence in human eyes is absolute.

So Hashimoto leans not on electrons, but on lookouts.

And the lookouts are exhausted.

They’ve been at their posts for hours, straining into the dark, beads of rain stinging their faces. Their world is a narrow circle of wet steel, the endless hiss of water, and a night that seems to go on forever.

They are staring into walls of rain.

They see nothing.

One a.m.

Eight thousand yards.

Four miles.

Point-blank range for an 8-inch gun. A distance at which even a half-blind battleship could hit a destroyer.

The British are now well inside the range at which Haguro could erase them.

And still, the Japanese cruiser is silent.

For Power, that silence speaks louder than any gun.

If Haguro knew they were there, doctrine and instinct would drive her to open fire, to seize the initiative, to blast a path through.

The silence means something else: they are still unseen.

He edges his ships closer.

Saumarez and Verulam race ahead, straining to reach a position “across the T”—to cut in front of Haguro’s bow, forcing her either to turn and bleed speed or plow forward under sudden torpedo fire.

Venus and her sisters hang back, to the south and east, waiting with torpedo crews at their stations, capstan heads ready, warheads armed, tubes trained.

The trap is almost fully built.

But the ocean is stubborn. It rarely lets a plan unfold without a twist.

Six thousand yards.

Three miles.

On Haguro’s starboard quarter, one of the lookouts rubs his eyes and squints through the sheets of rain. For a heartbeat, he thinks he sees something on the horizon—a break in the darkness, a darker shape in the black.

“Possible contact, starboard aft!” he shouts.

The call reaches the bridge, where Hashimoto stands beside Captain Sugiura, the ship’s commanding officer. Their heads snap toward the starboard windows.

“What did he see?” Sugiura demands.

“A shape, sir. Might be a ship. Might be… a cloud.”

They turn to the radar. The screen is smeared with clutter. Returns spike and vanish. Nothing stands out.

They glance at the chart. They are supposed to be alone. Their last intelligence said no major Allied units were near.

If they assume it is an enemy destroyer and order fire—and it turns out to be nothing but a squall—they waste ammunition and broadcast their position to any lurking submarine or aircraft.

If they assume it is a cloud and do nothing—and it turns out to be a destroyer—they may have just handed the enemy the first shot.

It is the horrible calculus of war.

In a video game, you shoot at the red dot. In reality, you hesitate.

You hesitate because your ship is irreplaceable metal and irreplaceable lives and your orders are to avoid battle if you can.

On the British side of the strait, there is no such hesitation.

On Saumarez’s plot table, the lines are crisp. The range is known. The bearing is fixed. Haguro’s movements are a series of angles and distances, turning into firing solutions.

The destroyers are now so close that radar is almost a luxury. Dark hulks are becoming faint shapes against the gloom.

They are entering torpedo range.

Torpedo officers peer through their director sights, dialing in target speed and angle on the bow, calculating gyros.

They are not looking for a fair fight.

They are setting up an execution.

And then the sea itself plays its last card.

Haguro reacts.

Just after one-oh-five, the cruiser alters course—but not in a wild evasive turn.

She does not wheel away in panic. She does not turn directly toward the faint radar ghosts.

Instead, she makes a routine zigzag. A few degrees to port. A change dictated by habit and heavy seas, not by enemy contact.

In the darkness, the turn hardly feels like anything at all. The helmsman adjusts the wheel. The bow digs slightly differently into the water. Men on deck lean, then right themselves.

But on the plotting table, the new course line is everything.

That small alteration nudges Haguro closer to the northern British ships and away from those to the south.

For a few minutes, it looks as if she might slip between the jaws of the trap—threading the gap between Saumarez to the north and Venus to the south, sprinting through the star before it finishes closing.

Power watches the grease pencil strokes.

He knows he is out of time.

He cannot wait for the perfect, perfectly synchronized attack from all points of the compass.

If he hesitates, his carefully crafted box will collapse, and a lumbering cruiser with ten guns will break past his divided force.

“The silent phase is over,” he murmurs.

He signals his ships.

Prepare to illuminate. Prepare to fire.

And down to the south, on HMS Venus, a different drama is unfolding—one that will give the battle its bitter title.

Commander E. J. “Jake” Dales stands on the bridge of Venus, his hands wrapped around the rail as if he can feel the enemy through the steel.

The night presses close. Men from the torpedo crews wait beside gleaming tubes, fuses set, doors cracked open. Gunners stand by their main guns, fingers itching for the order.

Somewhere in the rain to the northwest, the silhouette of Haguro looms—dark on dark, a shadow that looks like every nightmare a destroyer captain can have.

She is within range.

Venus’s Mark IX torpedoes can reach her from here. Venus’s guns can certainly lob shells into her side.

Every nerve in Dales’ body screams to open fire.

But he looks at the angle.

Haguro is steaming past on a course that takes her away from Venus, at a narrow angle, her stern angled toward the destroyer.

If Venus fires now, the torpedoes will have to chase her, angling in shallow lines that might result in glancing blows or near-misses. The track angle—how squarely a torpedo will hit the hull—is poor.

A mediocre shot.

And he has been briefed. He knows how few heavy cruisers the Japanese have left—and how badly his own flotilla needs this kill.

He can take the easy shot now and hope.

Or he can do the most unnatural, counter-instinctive thing a combat officer can do: hold his fire and let a prime target pass by, gambling everything on a better chance later that may never come.

Dales chooses the gamble.

“Hold fire,” he says.

His gunnery officer blinks at him. “Sir, we have—”

“I said hold fire.”

He orders his crews to stand down. No shells. No torpedoes.

He watches as the bulk of Haguro’s shadow slides by in the dark, only a few thousand yards away.

Every second of silence feels like an eternity wasted, like courage turned to stone.

But Dales is not being timid.

He is acting like a sniper who lowers his rifle because the crosswind isn’t right yet.

He is betting everything that the trap is working. That Saumarez and Verulam in the north will force Haguro to turn. That the Japanese admiral, seeking to run from the threat he can see, will unwittingly expose his side to the danger he cannot.

Two minutes pass.

Then three.

The tension on Venus is electric. Torpedo men shift their weight from foot to foot. Someone swallows audibly in the quiet.

If Haguro keeps steaming southeast, she will open the range and escape.

At ten past one, the trap finally springs—not from Dales’ ship, but from Hashimoto’s mind.

On Haguro’s bridge, reports finally fall into a pattern too clear to ignore. The shapes to the north are no longer maybe-clouds. They are destroyers—and they are closing fast.

Hashimoto doesn’t know exactly how many. He doesn’t know what lies beyond them in the dark. All he knows is that gun flashes may come any moment from that direction, that torpedoes may already be in the water ahead.

He makes a decision that seems entirely logical:

Turn away from the threat.

He orders hard starboard. New course: due south, back toward the relative safety of Singapore and the wider sea.

He thinks he is presenting his stern to the enemy, reducing his profile, making himself a longer, narrower target. It is a classic defensive turn.

He does not know that Venus is waiting in the south, silent, torpedo tubes trained on the empty patch of ocean into which he has just ordered his ship to steer.

Physics takes over.

Haguro heels to starboard as she begins her turn, her bow carving a wider circle in the water. At twenty-eight knots, she throws up a strong wake, rudder biting deep. She slows as the hull fights the water.

From Venus’s bridge, Dales watches the silhouette change.

A minute ago, he could see mostly Haguro’s stern—narrow, small.

Now, as the cruiser swings south, she shows more and more of her side. Her flank grows longer and longer. Her profile widens from a wedge to a slab.

Within moments, she is presenting six hundred feet of steel broadside, almost perfectly perpendicular to Venus’s torpedo tubes.

A wall.

The torpedo solution shifts from poor to perfect almost at once.

“Target: heavy cruiser, port side,” the torpedo officer calls. “Speed, twenty knots. Angle on the bow, ninety green.”

A ninety-degree track is the dream—torpedoes slamming straight into the hull like fists into a chest, not glancing blows along ribs.

Range: four thousand yards.

Three thousand.

Two thousand.

The two ships are now essentially on parallel courses, going in opposite directions—like cars passing each other on a highway—only a mile or so apart.

Hashimoto has unknowingly placed his ship inside the no-escape zone of British torpedoes.

On Venus, Dales feels the moment arrive like a weight settling.

“Stand by tubes one through six.”

Men tense. Fingers curl around levers.

This is why he waited.

If he had fired nine minutes earlier, he might have wasted his spread, his fish foaming uselessly through empty sea.

Because he stayed silent, because he endured those long minutes of doubt, he has been handed the kind of shot destroyer captains dream about and almost never get.

Haguro is between hammer and anvil.

Saumarez and Verulam close in to the north. Venus and the others bracket the south and east. The points of the star are converging.

And time has run out.

On Haguro, the lookouts finally see the nightmare they have been half-imagining for the last twenty minutes.

A destroyer, close. Too close. The flare of movement along its side: torpedo mounts swinging, men working in silhouette.

“Destroyer to port! Torpedo launch!” someone screams.

Hashimoto shouts orders. Sugiura calls for rudder hard over. The helmsman spins the wheel.

But thirteen thousand tons of steel cannot sidestep like a man.

Once a ship that big commits to a hard turn, her momentum owns her. She will slide through the water, carried by the mass and speed she had moments before.

The geometry is written.

Torpeodes do not care about shouting officers.

On Saumarez, Captain Power knows the time, too.

“Switch on the searchlight,” he orders.

A crewman throws a lever.

With a hiss and a crackle, a twenty-inch carbon-arc searchlight sputters to life. A beam of blinding white rips across the dark sea, slicing through rain, catching spray and making it glow.

It finds Haguro like a finger of judgment.

For the Japanese crew, the psychological shock is total.

One instant, they are surrounded by blackness, their world defined by vague shadows and the memory of their own hull beneath their feet.

The next, a sun ignites a few thousand yards away.

The glare sears their eyes. Men flinch, throw up their hands. The ship’s gray sides leap into stark relief, every gun, every vent, every ladder suddenly naked before the light.

Training takes over.

The gunnery crews on Haguro had drilled for exactly this kind of moment in a hundred exercises before the war.

They do not need radar now. They have a light to kill.

Within seconds, Haguro’s main battery speaks.

Ten 8-inch guns, arranged in five twin turrets, elevate and train with a speed that belies their size. Fire-control crews work frantically, spotting, adjusting, shouting corrections.

The first salvo lands close, throwing up pillars of water around Saumarez.

The second finds her.

An 8-inch high-explosive shell smashes into Saumarez’s funnel, punching through metal and tearing into the spaces below. It bursts in or near the boiler room.

Superheated steam screams out of ruptured pipes, a white, scalding fog that kills five men before they can even cry out. The blast rocks the destroyer, rattling her frame, pitching men off their feet.

She staggers. Her speed drops.

In a fair fight, this is where Haguro would win. She has found her target. It is lit and wounded. Her guns outrange anything the British can bring against her.

But this is not a fair fight.

The searchlight is, in a cruel way, a lure. While Haguro’s main guns focus on the burning spear of light, while men on her decks swear and bleed and shout amid flying steel, the real killers are already moving toward her in the water.

From the port side, Saumarez and Verulam have already launched, each ship spitting out four Mark IX torpedoes.

From the starboard side, Venus has let loose six of her own.

Fourteen steel sharks, running fast at forty-five knots, each carrying an 800-pound Torpex warhead in its blunt nose.

They form converging paths around Haguro, a crossfire pattern that, in naval theory, is the deadliest formation torpedoes can be given.

Hashimoto’s crew fights their ship with all the skill of a navy that prided itself on gunnery and discipline.

They try to maneuver. Sugiura orders hard rudder again, desperate to comb through the spread, to turn the ship so that torpedoes pass harmlessly along her length.

But Haguro’s speed has already been cut by her earlier turn. The water is shallow and treacherous here. She cannot swing like a small destroyer.

Time, and distance, are gone.

The first torpedo hits.

The impact comes forward of the bridge on Haguro’s port side.

Men topside see a sudden tower of water erupt, hundreds of feet high—a white, roaring column shot through with jagged chunks of steel. The sound is a flat, monstrous crack that seems to punch the air itself.

Below decks, in compartments no one on the surface has ever seen, the world simply disintegrates.

A wall becomes a pressure wave. A corridor becomes shrapnel.

The bow shudders. Structural members bend and snap. Plates buckle. Water rushes in through a crater where the hull used to be, the sea suddenly inside the ship.

Almost instantly, Haguro’s speed drops, her forward momentum bled away as thousands of tons of water slam into and around her frame.

She begins to list, ever so slightly, to port.

Impact two follows seconds later, closer to midships on the same side, likely one of Verulam’s fish.

This one is the true crippler.

The explosion tears into the engineering spaces. Boilers—already straining to drive the ship at high speed—are torn open. Steam lines burst. Electrical systems short.

Below, in the engine room, men are flung like rag dolls. Lights flicker, then die.

The thrum of Haguro’s propellers, that constant vibration that has been beneath every sailor’s feet for hours, falters and stops.

The ship is now dead in the water.

Her list to port increases. Five degrees. Ten. Fifteen.

From the starboard side comes the third blow—one of Venus’s torpedoes slamming into the other flank.

The result is devastating in a way that even Haguro’s builders never fully modeled.

A ship’s hull is a long girder, a spine of steel meant to take forces from waves punching at the bow, from recoil, from emergency maneuvers.

It is not meant to absorb near-simultaneous explosions on opposite sides.

The shock waves twist her. Her keel, the backbone of the ship, groans under torsion, bending where no designer ever intended it to bend.

Plates pop. Rivets shear. Bulkheads crack.

Now the cargo takes its toll.

The bags of rice, the crates, the drums stored on deck—those improvised signs of a starving empire—become deadly.

As Haguro lists, gravity pulls on hundreds of tons of poorly secured material.

Crates break loose. Sacks rupture. Drums roll.

The mass of it all slides across the deck, smashing into gun mounts, shattering vents, pinning men against railings.

It all piles on the low side, the port side, dragging her even farther over.

Damage-control parties cannot move freely. Paths are blocked by fallen cargo. Hoses tangle around spilled crates. Men wade through slopping mud of rice and oil and seawater.

Fuel drums rupture, their contents feeding fires that leap along the ship’s length.

And yet, the Haguro does not surrender.

This is the last stand.

Her bridge may be damaged, her power failing, but her guns still work—as long as men can manually crank them.

The sailors of the Imperial Navy live up to their brutal reputation.

Amid the chaos—smoke, the rising deck angle, the screams of wounded—they keep loading shells, keep swinging turrets by hand, keep firing at the destroyers that circle them like wolves.

They hit Saumarez again. They throw shells toward Venus, toward the others. They refuse to be quiet prey.

On the bridge, Hashimoto and Sugiura know the truth.

Three torpedo hits. Fires. A broken spine. No power. No way to escape or maneuver.

There is no damage-control scenario for this. No amount of heroism can un-snap a keel.

They give the order no captain ever wants to give.

“Abandon ship.”

But the order meets ugly reality.

Lifeboats have been splintered by blast or pinned beneath shifted cargo. Some sit uselessly at impossible angles as the list increases. Others are on the high side, out of reach for men already scrambling along railings that have become floors.

Many will have no choice but to jump.

Into the night.

Into water slick with oil, shadowed by debris, echoing with the groan of wounded metal.

By two in the morning, Haguro’s list has reached thirty degrees.

The bow dips lower and lower. Waves begin to wash over the forecastle.

From the British destroyers, now at a safer distance, the view is simultaneously majestic and horrifying—a great ship in her final convulsions.

They watch her stern rise, propellers lifting free of the water and hanging in the air like the exposed bones of some gigantic beast.

There is no spectacular magazine explosion, no single fireball.

Just a slow, inevitable sinking. The groaning of tortured steel gives way to the hiss of water pouring into new spaces. Air roars out of vents as it is forced by the inrushing sea.

At 2:32, Haguro slides beneath the surface.

Dark water closes over her.

Around nine hundred men go with her, pulled down by suction, trapped in compartments, dragged under by life vests saturated with oil and water.

Hashimoto is gone. Sugiura is gone.

The surface of the Malacca Strait seethes with debris and struggling men, then slowly calms.

On Saumarez, Venus, and Verulam, radar operators watch their screens.

The green blip that appeared ninety minutes earlier is gone.

The geometry is resolved. The star of destroyers closes ranks, its deadly purpose fulfilled.

The ocean is functionally empty again.

But in that emptiness lies the memory of a ship that fought a war already lost, using tools that no longer ruled the night.

In the days and decades that follow, historians will describe the destruction of Haguro as a triumph of British destroyer tactics.

It is.

But under the thunder and the heroism and the dramatic searchlights, there is a colder truth.

Haguro did not die because her crew was incompetent.

Her gunnery, in the brief moments she could bring her guns to bear, was precise. She found Saumarez quickly and hit her hard.

Her lookouts were not lazy. They stared into rain and darkness until their eyes ached.

Her officers were not cowards. They tried to maneuver, tried to obey orders to preserve their ship.

She died because the system that had built her—the doctrine that had trained her crew and shaped her equipment—was obsolete in that place and hour.

The Imperial Japanese Navy had built its reputation on night fighting.

Japanese officers believed that, properly trained, human eyes and ears were the ultimate sensors.

On May 16th, 1945, that belief became a liability.

The core failure on Haguro was the verification gap.

The British destroyers operated on something like instrument flight rules.

Captain Power trusted his radar implicitly. To him, a blip was a target. He maneuvered based on data.

The Japanese were operating on visual flight rules.

Their doctrine demanded visual confirmation before action. To Hashimoto, a radar return was an untrustworthy hint.

This difference created a fatal delay in the OODA loop: observe, orient, decide, act.

While Haguro’s officers spent precious seconds and minutes trying to verify reality with binoculars and flawed radar, the British were already shaping reality with torpedoes.

By the time Japanese lookouts could say with certainty, “Yes, that is a destroyer,” the destroyers had already moved from approach to execution.

Layered over that was the defensive mindset of a navy Hoarding its last capital ships.

Hashimoto’s mission was to save his ship, not seek battle glory.

That shaped his decisions: turning away from the visible threat in the north, not knowing he was turning directly into an invisible net to the south.

He made a rational decision based on incomplete information.

He was playing checkers on a board that his opponent was seeing in three dimensions.

When he ordered that hard turn to the south, he believed he was reducing his vulnerability.

In reality, he was creating the perfect broadside for Venus.

The nine minutes that followed—from the moment Dales on Venus first had a marginal shot to the moment Haguro swung broadside—were the space where the old world died.

Nine minutes in which a destroyer captain chose discipline over impulse, held his torpedoes in their tubes, trusted that the geometry would improve.

Nine minutes in which Japanese officers stared into rain, half-seeing shapes, hoping for emptiness.

Nine minutes Haguro never got back.

When the torpedoes left their tubes, when the searchlight came on, when 8-inch shells slammed into Saumarez’s boilers and fourteen cylinders of British steel crossed paths beneath the waves, those nine minutes had already decided everything.

The age of vision—of warships ruled by what men could see, of admirals betting on sharp eyes and clear nights—was dying there in the Malacca Strait, on a stormy night, under green radar glow no Japanese sailor could feel.

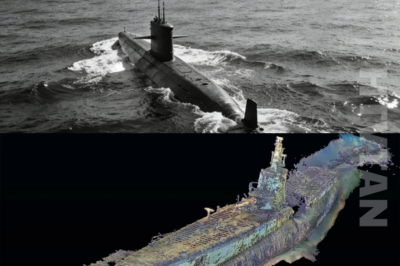

Haguro lies there still, twisted on the seafloor, her guns silent, her deck cargo long rotted away.

She does not rest there because her crew lacked courage.

She rests there because her navy clung too long to an operating system that demanded proof of danger before it allowed its ships to act.

In 1942, that doctrine had been deadly.

In 1945, it was fatal.

And in the space of nine irrevocable minutes, one missed warning and one act of restraint turned a ghostly radar blip into a finished kill—showing, for anyone willing to learn, that in modern war the first side to believe its instruments, trust its calculations, and act on them without waiting to see with naked eyes, owns the night.

News

CH2. Why One U.S. Submarine Sank 7 Carriers in 6 Months — Japan Was Speechless

Why One U.S. Submarine Sank 7 Carriers in 6 Months — Japan Was Speechless The Pacific in early 1944 didn’t…

CH2. German Commander’s Last 90 Seconds – The Weapon That Destroyed 47 U-Boats

German Commander’s Last 90 Seconds – The Weapon That Destroyed 47 U-Boats The sea looked wrong. Kapitanleutnant Bernhard Müller had…

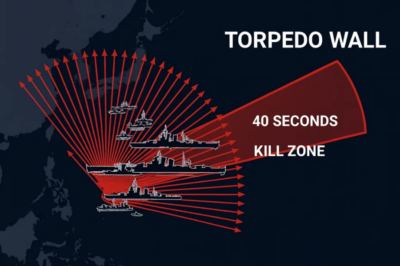

CH2. The 40-Second Torpedo Wall — How 22 Shots Erased Japan’s Night-Fighting Advantage

The 40-Second Torpedo Wall — How 22 Shots Erased Japan’s Night-Fighting Advantage The date was August 6th, 1943. The place:…

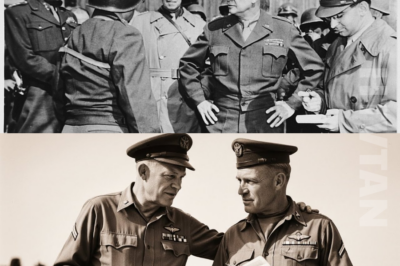

CH2. What Eisenhower Said To His Staff When Patton Crossed the Rhine Without Orders!

What Eisenhower Said To His Staff When Patton Crossed the Rhine Without Orders! March 22nd, 1945, was supposed to be…

CH2. Why Japanese Admirals Stopped Underestimating American Sailors After Midway

Why Japanese Admirals Stopped Underestimating American Sailors After Midway Commander Joseph Rochefort had forgotten what it felt like to be…

CH2. How One Sniper’s “STUPID” Mirror Trick Outsmarted the Germans Snipers

How One Sniper’s “STUPID” Mirror Trick Outsmarted the German Snipers November 3, 1944 Metz, France The wind off the Moselle…

End of content

No more pages to load