In 1940, before anyone in Farmersville, Detroit, or Brooklyn had heard of places like Kasserine or Tarawa, the United States Army owned fewer than five hundred tanks.

Its air force was smaller than Portugal’s.

On paper, it was a second-rate military power, a country that still thought in terms of oceans as walls and the Atlantic as somebody else’s problem.

In the War Department, a few generals stared at maps and saw a storm coming. In Berlin and Tokyo, other men stared at their own maps and smirked.

“They can’t touch us,” one German staff officer said, running a finger across the Atlantic. “They do not have the army. They do not have the planes.”

What he didn’t understand—what almost nobody understood in 1940—is that America’s most powerful weapon wasn’t in any arsenal.

It was the factory floor.

The man who would eventually notice that weapon first was not a general or a president, but a foreman at a Ford plant in Michigan.

His name was Frank Ricci. He’d spent the 1930s supervising a line that stamped out fenders and doors for Model As and pickup trucks. His days were measured in steel panels and whistle blows.

On a gray morning in 1941, long before Pearl Harbor, his district manager gathered the supervisors on the factory floor, voice echoing off the high rafters.

“Boys,” he said, “Washington wants to talk about airplanes.”

Frank looked around at the acres of presses and conveyors and oil-stained concrete and tried to imagine wings and fuselages where car bodies now hung.

He couldn’t quite see it.

Not yet.

But by 1944, he’d stand at the end of the Willow Run assembly line and watch a fully built B-24 Liberator roll off the line every sixty-three minutes—one bomber an hour. Eighteen thousand four hundred B-24s would leave American factories before the war ended.

The German officer had been wrong.

America could touch them.

It would touch them with aluminum and rivets, truck frames and tank treads, rifles and pistols, and with twelve billion half-inch-wide pieces of brass and lead.

Joe Miller first heard the word “arsenal” on his father’s radio.

He was a farm kid from Ohio who had never been farther east than Cleveland. That December night in 1940, the family sat around the big wooden set, listening to President Roosevelt’s voice hum through the mesh speaker.

“We must be the great arsenal of democracy,” Roosevelt said.

Outside, the wind whispered against the barn. Inside, Joe’s father leaned forward, elbows on his knees.

Joe was seventeen, all long arms and restless energy. The words meant something to his father, a man who’d watched the Depression chew through neighbors’ farms. To Joe, they sounded like the introduction to a story he didn’t know the ending to yet.

Arsenal.

He pictured rows of guns in a room somewhere. He didn’t understand that what Roosevelt was talking about wasn’t a room full of rifles.

It was Detroit.

And Pittsburgh.

And tiny machine shops in towns like his own.

It was every factory that could be turned from making toasters and cars and sewing machines into making something else: weapons, parts, ammunition.

By the time Joe turned twenty-one, that vague speech would become his entire world.

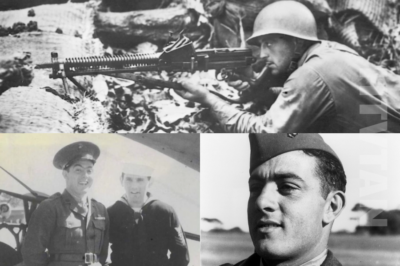

In 1942, just months after Pearl Harbor turned every “what if” about war into a hard reality, Joe stood in line at the recruiting office with a dozen other boys from his county. The posters on the wall showed Shermans and planes and men charging forward, their faces set.

“What do you want to be?” the recruiter asked, looking at his paperwork.

“Infantry,” Joe said.

The recruiter lifted an eyebrow. “You sure? We got the Army Air Forces. We got the Navy. We got armor. Infantry’s where the walking and dying happens first.”

Joe thought about it.

Somewhere overseas, men were already dying in places like Bataan and the North Atlantic. Someone had to go. Someone had to carry the rifle that would meet whatever the factories back home were sending.

“Infantry,” he said again.

The recruiter shrugged and stamped the form.

Behind him in line, a skinny kid named Luis said, “Tank corps for me.” Another, named Eddie, said, “I’ll take anything with an engine. Maybe trucks.”

They didn’t know it yet, but between Joe with his rifle, Luis in a Sherman, and Eddie in a deuce-and-a-half truck, they’d represent the three layers of something bigger.

Teeth. Armor. Skeleton.

And back home, Frank in Detroit would be the beating heart.

In England, late 1943, a sergeant handed Joe a long wooden crate.

“Merry Christmas,” the man said. “Meet your best friend.”

Joe pried open the crate and pulled out a rifle: walnut stock, steel receiver, heft heavy and solid enough to feel like an anchor and a promise.

“U.S. Rifle, Caliber .30, M1,” the sergeant recited. “We call it the Garand. General Patton says it’s the greatest battle implement ever devised. Treat it right, it’ll do the same for you.”

Joe wrapped his fingers around the stock. It felt alive.

He’d drilled with Springfields before, old World War I bolt-actions. They were fine rifles—but this… this thing swallowed an eight-round clip with a satisfying metallic click and spat them out one after another as fast as he could work the trigger.

No bolt to cycle. No break in the rhythm.

“This is semi-automatic,” the sergeant said. “You can put eight rounds downrange before a Kraut with a Mauser has worked his bolt for his second shot. Remember that.”

Behind Joe, a corporal with a clipboard muttered numbers as rifles were issued.

“Five point four million,” he said under his breath. “That’s how many they say we’ll have before this is done.”

Joe couldn’t comprehend a number like five million.

He could comprehend this one rifle.

He pulled the charging handle, watched the bolt slam forward on an empty chamber, and imagined the cartridge it would one day push into place: brass case, powder, bullet.

In some plant in Illinois, a woman named Sarah was making those cartridges.

Sarah worked at the Lake City Army Ammunition Plant, a place that had been cornfields before the war.

In 1942, she had been a schoolteacher. By 1943, she was standing in front of a stamping press that turned brass cups into cartridge cases by the thousand.

The floor shook with the force of the machines. The air smelled of oil and metal and the faint acidic tang of priming compound.

On her first day, an older woman named Helen had handed her a pair of safety glasses and a simple truth.

“These,” Helen said, holding up a handful of finished .50 caliber cartridges, “are what stand between those boys and never coming home.”

Sarah had run her fingers along the cool brass. Half an inch wide. Nearly six inches long. Each one a promise of violence.

“We make them right,” Helen said. “Every time. No excuses.”

By the end of the war, American factories would make over twelve billion of the .50 Browning Machine Gun cartridges Helen had held—twelve billion half-inch-wide arguments making their way into German bombers, Japanese fighters, armored cars, trucks, tanks.

Sarah never saw the guns that fired them. But in Italy, a B-24 tail gunner named Murphy did.

Murphy lay on his stomach in the tail turret of a B-24 Liberator high over Ploiești, Romania, sweat freezing on his neck.

Outside, flak blossoms dotted the sky, black puffs that reached up with jagged fingers. The Liberator’s Davis wing flexed, the plane fighting through the turbulence.

“Bandits six o’clock low!” someone screamed over the interphone.

Murphy saw them.

Messerschmitts and Focke-Wulfs climbing to meet them, specks at first, growing rapidly. The sight should have frozen him. Instead, muscle memory took over.

His hands clamped the butterfly triggers of the twin .50 caliber M2 Brownings in his turret.

The guns were mounted like extensions of his arms. Each one chewed through belts of ammunition—tracer, ball, armor-piercing, incendiary—feeding from ammunition boxes stuffed with those same cartridges Sarah had inspected on a Missouri factory floor.

He squeezed.

The Brownings roared, a steady staccato that vibrated his entire body. Brass casings cascaded into catch bags; smoking links spiraled away behind the plane.

He watched his tracers arc out, white lines against the dark speckled sky, walking them into a German fighter’s path.

Twelve billion rounds.

He only needed a handful right now.

One of his streams found its mark. The German plane’s wing root blossomed in flame. It rolled, trailing smoke, and spun away.

Murphy didn’t cheer. He just shifted his aim to the next attacker.

The B-24 he rode in was one of over eighteen thousand four hundred built—the most produced American bomber of the war. Consolidated, Ford, and other companies had turned aluminum and rivets into these sky-borne beasts at a pace German factories couldn’t believe.

From above, they looked like swarms of metal locusts. From below, they sounded like doom.

But for Murphy, right now, the war existed in the vibrations of twin .50s and the faint whiff of cordite leaking into his turret.

Every squeeze of the trigger traveled back along a chain:

From his hands, to the guns, to the belts of ammunition, to Sarah’s station on the factory floor, to a pile of brass cups being stamped into cases.

The arsenal of democracy, compressed into the space between his finger and a gun’s recoil.

On the ground, the war looked different—but the chain was the same.

Joe first met a bazooka outside a village in Normandy that no longer looked like a village.

The church steeple had collapsed into the square. Houses burned. The air was full of dust and the distant rumble of armor.

He’d learned about the “M1 Rocket Launcher” in training—a long tube, a shoulder-fired hope against tanks. Now he watched a sergeant named Collins slap a rocket into the rear of it and rest it on his shoulder like a man hefting a fence post.

“There,” Collins said, nodding toward the edge of the village, where a German tank lurked behind a shattered wall. “Panzer.”

Joe saw only the faint suggestion of a muzzle, the ghost of a barrel.

“You sure?” he asked.

“Do you wanna walk up there and ask?” Collins snapped.

The bazooka was a simple thing compared to the machines in the sky. A tube, a battery, a trigger, and a shaped-charge rocket.

Cheap. Effective.

America would build nearly half a million of them—over 476,000—and ship them anywhere a man might need to stop a tank with something he could carry on his shoulder.

Collins called for covering fire.

Joe and the rest of the squad leaned out from shell-scarred corners and fired their Garands, the eight-round clips pinging empty and flying free as they slammed fresh ones in.

The Panzer’s gun swung, searching.

Collins squeezed the trigger.

The rocket whooshed from the tube, a line of smoke marking its path. For a heartbeat, it seemed slow, hopelessly slow.

Then it struck.

The shaped charge didn’t need velocity. It bit into the armor and focused a jet of molten metal inward.

The tank shuddered. Smoke poured from its hatches. One by one, black-helmeted figures tumbled out, some on fire, some with arms raised.

“Reload!” Collins barked.

Joe shoved another rocket into the back of the tube, his fingers trembling, not from fear now but from a rush of relief so sharp it hurt.

The tank had been a monster a minute ago.

Now it was wreckage.

Back home, somewhere in an American plant, a worker on a line had riveted that bazooka together, not knowing which man would fire it. Now the answer was here, in this ruin of a village, in this second where German steel died under an American contraption that cost a fraction of its target.

Not every weapon was as dramatic as a bazooka or as iconic as a B-24.

Some of the most important ones were almost boring to look at—until you tried to run a war without them.

Eddie, the kid who’d wanted anything with an engine, got his wish.

He got trucks.

Specifically, he got the GMC CCKW 2½-ton truck: the “deuce-and-a-half.”

The first time he saw a motor pool full of them in North Africa, his jaw literally dropped.

Olive-drab noses. Canvas-covered backs. Rows and rows and rows.

“Pick one,” the motor sergeant said. “And don’t wreck it.”

Eddie climbed into the driver’s seat of his assigned truck and felt a thrill that surprised him. It wasn’t a tank. It wasn’t glamorous. But when he wrapped his hands around the wheel, the war suddenly had a shape he understood.

Haul. Deliver. Repeat.

Patton’s Third Army would later say it would have ground to a halt in France without those trucks. That wasn’t hyperbole. Gasoline, ammunition, food—none of it moved without wheels.

Over 562,000 of those GMC trucks rolled out of American factories. On the Red Ball Express, they lined roads from Normandy beaches to front lines, bumper to bumper, hauling day and night.

Eddie’s job was simple on paper.

Drive ten, twelve, fourteen hours.

Eat when he could.

Sleep when the schedule allowed.

Watch the gauges. Listen to the engine.

Actually doing it meant dodging potholes, enemy aircraft, and fatigue that turned the world into a blurred tunnel of headlights and taillights.

One night, grinding up a French hill in second gear with a load of fuel drums for a tank battalion up front, he heard the distant thump of artillery and saw flashes on the horizon.

“Hope those boys like walking,” his buddy in the passenger seat said.

Eddie shook his head. “Not if I can help it.”

He slapped the dashboard.

“Come on, girl,” he said to the truck. “Just a little farther.”

The deuce-and-a-half grumbled, then pushed on.

Behind them, in a long snaking line, hundreds of other trucks followed, each one a vein feeding blood to the front.

Germany had trucks, too. But not enough. Never enough. And theirs burned fuel they were starving for.

American factories, untouched by bombs, produced wheeled miracles faster than German factories could replace losses.

You don’t win a war just by firing bullets.

You win it by making sure your bullet-firing men are never hungry, never out of gas if you can help it, never missing the tools they need.

Eddie drove, and in his way, he was firing shots, too.

Some weapons weren’t big, but they were everywhere.

In North Africa, a lieutenant in khaki leaned against the hood of a small, stubby-nosed vehicle and wiped sweat from his brow.

It was 120 degrees in the shade, and there wasn’t much shade.

The vehicle had no doors. Its windshield folded down. It rattled over rocks without complaint, hauled wounded men to aid stations, carried officers to command posts, mounted machine guns when needed, and bounced through wadis and scrub like a goat.

“Best damn thing we ever built,” the lieutenant said, patting the fender. “Don’t know how we’d do this without it.”

It was the Jeep.

Officially, the ¼-ton 4×4 truck. Unofficially, the answer to a thousand questions.

Need a scout car? Jeep.

Need a field ambulance? Jeep.

Need to tow an anti-tank gun? Jeep.

Need to move wire, ammo, rations, staff officers, or even a general with a pipe in his teeth and a map on his knees? Jeep, Jeep, Jeep.

It was simple enough to fix with basic tools. Tough enough to ford rivers and grind up hillsides. Light enough to sling in a glider or cram into a ship’s hold.

Nearly 650,000 Jeeps came out of plants at Ford, Willys, and others. In England, kids watched them rumble past and shouted. In Russia, soldiers grinned and dubbed them “little Americans” as they drove them into mud German vehicles couldn’t cross.

In towns from Normandy to the Philippines, the silhouette of a Jeep bumping over rubble became shorthand for one thing.

The Americans are here.

Back on the line, Joe learned that not every man could carry a full-length Garand all day.

Clerks, drivers, mortar crews, radiomen—men whose main job wasn’t to charge with rifle and bayonet needed something handier than a pistol but lighter than a battle rifle.

That something showed up in crates marked “CARBINE, CAL. .30, M1.”

Joe watched as a supply sergeant pulled one out and handed it to a fresh-faced kid assigned as a radio operator.

The carbine looked almost like a toy compared to the Garand. Smaller stock. Slim barrel. Fifteen-round magazine.

“Don’t let its size fool you,” the sergeant said. “She’ll reach out as far as you’ll probably need, and she’s light enough you won’t hate me for giving it to you.”

Over 6.1 million of those M1 Carbines rolled off lines, more than any other American small arm of the war. They rode in Jeeps, dangled from the shoulders of paratroopers and engineers, hung on pegs in command posts, and leaned against foxhole walls.

In the Ardennes, a clerk who’d thought he was safely behind the lines used one to fight off a German patrol during the Battle of the Bulge. In the Pacific, a Marine radioman clutched his to his chest as he dove into a shell crater on Peleliu.

The carbine was there whenever someone whose primary job was something else suddenly needed to become a rifleman.

If the Garand and the carbine were the arms of the American soldier, the M1911 pistol was the heartbeat.

In foxholes, on flight decks, in tank turrets, at airfields, in the holsters of MPs and officers and NCOs, that big .45 rode on belts and in shoulder rigs.

Designed by John Browning before the last war, refined and adopted in 1911, the pistol had already seen decades of service by the time World War II erupted.

During the war, American factories produced 1.9 million more.

Joe watched his platoon leader, Lieutenant Harris, pull his out once after a firefight in Italy.

Harris’s hands shook as he reloaded his Garand. A German soldier, wounded, had drawn a concealed pistol and fired wildly from a ditch before a burst of covering fire dropped him.

Harris stared at the big Colt in his hand.

“Always have a backup,” he said quietly.

Joe nodded.

Later, in Aachen’s rubble-filled streets, when the range collapsed to ten yards and below, when Garands and carbines snagged on debris, it was the .45s that came out. The reports were deep, thudding, different from the sharper crack of rifles.

In the Pacific, pilots ditched at sea with M1911s in their survival kits, hoping never to need them but comforted that they were there.

Almost two million pistols, riding on hips and in holsters across the globe, each one stamped by a factory that had once made something else.

Typewriters. Sewing machines.

Now, they made the punctuation marks of close combat.

Somewhere in a trench outside Leningrad, a Soviet infantryman wrapped his hands around the wooden grips of an American-made Thompson submachine gun.

The heavy steel receiver was marked “AUTO-ORDNANCE CORPORATION.” The box magazine locked in with a solid chunk.

The gun weighed more than ten pounds, heavy for a submachine gun. Its complexity and cost meant American factories only built around 1.5 million of them, before switching to simpler designs like the M3 “grease gun.”

But here, in this frozen hole, none of that mattered.

The Russian’s breath steamed as he fired short bursts into a snow-swirled no-man’s-land. The .45 ACP rounds hammered out, each one another handshake from American industry.

In another American squad, a BAR man—a Browning Automatic Riflener—hunched behind his twenty-pound weapon, firing controlled bursts while his buddies moved.

“Cornerstone of the rifle squad,” their doctrine said.

Only about 400,000 BARs were built, far fewer than some other weapons. But in Italy’s mountains and France’s hedgerows, those men with BARs became the small anchors that held firefights together.

They weren’t the star of the production show, not like the Garand or the carbine. But they were part of the same avalanche.

Every time a Thompson or BAR barked, it was a reminder that America didn’t just make one kind of weapon.

It made everything.

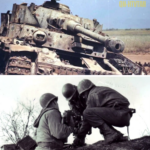

In 1944, a German panzer commander named Hans stared through his periscope at a valley in France and felt something cold in his stomach that had nothing to do with the wind.

He commanded a Panther tank, one of the best armored vehicles ever built—on paper. Its sloped armor could shrug off most enemy rounds frontally. Its long 75mm gun could kill a Sherman at well over a mile.

When his unit had gone into action in 1943, they’d felt invincible.

Now, he saw five Shermans coming over the ridge.

Then ten.

Then fifteen.

Some were on roads. Some crashed through hedgerows in places his map said were impassable. Halftracks followed them. Jeeps darted like insects around their flanks. Trucks rumbled in the distance, dust rising.

His crew fired.

They killed one Sherman, then another.

But for each one that brewed up, three more seemed to appear.

He thought, not for the first time, about the orders he’d been given regarding his tank.

“Preserve it,” his colonel had said. “This vehicle is irreplaceable. We do not have enough. The factory in Germany cannot make them as fast as we lose them.”

Hans cursed under his breath.

What good was “irreplaceable” if it meant “too precious to risk the way we need to”?

Across the valley, an American lieutenant watched the same scene and thought something very different.

“Keep moving,” he yelled into his radio. “We lose one, we’ve got more coming up.”

He wasn’t being callous. He cared about his men. But he knew a fact Hans didn’t want to admit.

For every Sherman that went up in flames, American factories could send five more.

Detroit’s steel and the deuce-and-a-half trucks and Liberty ships and new Shermans pouring off the lines meant he could think about attacks in terms of odds, not irreplaceable jewels.

It was a brutal calculus.

But wars are brutal math.

And America’s numbers were insane.

In 1940, the idea that American industry could churn out 49,000 M4 Shermans would have sounded like science fiction.

By 1945, it was history.

The M4 wasn’t the best tank in any one-on-one duel. Its armor was adequate, not exceptional. Its gun could struggle against heavy German armor frontally.

But it was reliable. Easy to produce. Easy to fix in the field.

Factories like the Detroit Arsenal Tank Plant became places where steel plates became hulls, turrets, and tracks at a pace that made German planners sick.

In Africa, Sicily, Normandy, and the Philippines, Shermans rolled off ships in endless lines. Some were turned into flamethrower tanks, others into recovery vehicles, some into self-propelled guns. The basic chassis was a versatile, strong spine.

Hans, staring at a valley full of them, felt that in a way no production statistic could capture.

“What good is a tiger,” he muttered once, “in a forest of wolves?”

He knew exactly how many Tigers his army had.

He had no idea how many Shermans America had left to send.

It was more than he could kill.

The numbers stacked up everywhere.

Forty-one thousand M3 halftracks carried rifle squads into battle, armored boxes on treads that turned infantry into mechanized punches.

In one such halftrack, a machine gunner named Floyd stood behind an M2 Browning on a pintle mount, eyes scanning for threats as his vehicle bumped along a dusty Italian road.

The halftrack’s armor wouldn’t stop a heavy round, but it was enough to keep small-arms fire out.

Floyd’s fingers hovered over the triggers of the .50, the same round Sarah had inspected and Murphy had fired.

A plane roared overhead.

“Friendly,” the driver yelled.

Floyd relaxed—slightly.

The halftrack was their battle taxi. Their ambulance. Their supply truck. Their command post. It was a chameleon, the M3, converted to hold mortars, radios, anti-aircraft guns.

Forty-one thousand times, American industry had taken steel and rubber and engines and turned them into these strange half-truck, half-tank creatures.

They weren’t glamorous.

But they got men and weapons where they needed to go.

Back in Ohio, after the war, Joe sat at his kitchen table with a coffee mug and an old M1 Garand propped in the corner. He was thinner. His hair had a few strands of gray that hadn’t been there before Sicily.

His son, eight years old, climbed onto a chair and asked the question children ask about wars they’ve never seen.

“How’d we win, Dad?”

Joe thought about Garands and carbines and bazookas. About Shermans and halftracks and trucks. About the .45 on Harris’s hip and the .50s in a B-24’s tail. About Jeeps bouncing over ruts, bringing wounded men to aid stations.

He thought about the German he’d shot in a hedgerow, the Panther that had brewed up under a buddy’s bazooka, the deuce-and-a-half trucks rumbling through the dark like ghosts with headlights.

He thought about Frank in Willow Run, about Sarah in Lake City, about men and women he’d never meet but whose fingerprints were on every piece of gear he’d carried.

“We made more stuff,” he said finally. “And we made it faster.”

His son frowned. “That’s it?”

Joe smiled, a little sadly.

“No,” he said. “That’s not it. We had brave people. So did they. We fought hard. So did they. But we could replace what we lost. They couldn’t.”

He sipped his coffee.

“Thing about wars, kid… they’re not just about who’s braver. They’re about who can keep going when both sides are scared and tired and bleeding. We had factories that never got bombed. We had steel and oil and men and women who worked themselves half to death building what we needed.”

His son looked at the Garand.

“Is that why you came back?” he asked.

Joe thought of twelve billion .50 caliber rounds. Of five million Garands. Of six million carbines. Of hundreds of thousands of trucks, tanks, halftracks, planes, pistols.

He thought of the truck that had brought ammo up just in time outside Saint-Lô, and the ship that had carried his unit across the Atlantic, and the Jeep that had gotten a medic to his buddy in time.

“It helped,” he said.

The Axis powers had brilliant engineers.

They built Panzer IVs, Panthers, Tigers. They built Messerschmitts and Focke-Wulfs and Bf 109s and Ju 88s. The Japanese built Zeros that turned the early Pacific skies into killing fields.

But their factories fought with one hand tied behind their backs.

They lacked resources—oil, rubber, certain metals. They fought under bombs that fell on Hamburg, Essen, Tokyo, Nagoya. Their political leadership diverted resources to pet projects, to “miracle weapons,” to late-war rockets and jet fighters that arrived too late and too few.

America had its own inefficiencies, its own bureaucratic nonsense.

But it had something the Axis couldn’t match.

Space.

Oceans.

And an economy that, once fully awakened, was terrifying.

It built nearly 650,000 Jeeps.

Over 562,000 deuce-and-a-half trucks.

Forty-nine thousand Shermans.

Forty-one thousand halftracks.

Over 18,400 B-24s.

Roughly 5.4 million Garands.

Over 6.1 million carbines.

Around 1.9 million M1911 pistols.

Hundreds of thousands of bazookas.

And twelve billion .50 caliber bullets.

Those bullets stitched the sky over Ploiești, tore through the hulls of Japanese kamikazes, cut down attackers charging across Italian hillsides, and spat from tank cupolas at low-flying aircraft.

The numbers almost stop meaning anything when you pile them together.

But each one meant something very specific, to a very specific person, at a very specific moment when life hung on whether a gun fired or it didn’t.

Murphy in the tail turret.

Collins with the bazooka.

Eddie in his truck.

Floyd in his halftrack.

Hans staring at a valley of Shermans and realizing that all his skill couldn’t stop a flood.

Joe in his foxhole, feeling the weight of an M1 Garand in his hands and hearing the reassuring “ping” of an empty clip and the metallic slam of a new one.

In some German command post in 1944, a colonel ran his finger down a report.

Losses: X panzers, Y trucks, Z guns.

Replacements: numbers much smaller.

He rubbed his eyes.

“How many tanks did the Americans bring to Normandy?” he asked.

“Too many,” his operations officer replied. “And more arrive every week.”

The colonel laughed once, a short, bitter sound.

“We were never going to win this,” he said. “Not against a country that can afford to give every infantryman a semi-automatic rifle.”

In another office, across an ocean, an American production manager walked down a line of lathes and presses and shouted to be heard.

“Faster!” he said. “We’re not building refrigerators. We’re building Garands. Every one that leaves this plant is one more reason some kid comes home.”

Workers wiped sweat from their eyes and pushed through another shift.

Their backs ached. Their feet hurt. Their hands blistered.

But the parts rolled out.

Receivers.

Barrels.

Clips.

Cartridges.

Everything.

Wars are won in muddy fields, in cold foxholes, in the thin space between a man’s fear and his training.

They’re also won in fluorescent-lit factories at 2 a.m., by a woman checking tolerances on a bolt, by a man stacking crates of ammunition, by a truck driver hauling steel across a continent.

The Axis lost for many reasons: strategic miscalculations, horrific moral choices that drained their strength, underestimation of their enemies.

But one quiet, relentless reason was this:

They could not match the sound of Detroit at full throttle.

They could not match the thunder of Willow Run’s assembly line, rolling a B-24 out every hour.

They could not match the ceaseless clatter of presses stamping out .50 caliber cases by the millions.

They could not match twelve billion bullets.

In 1940, the United States was a sleeping giant.

By 1945, it was an avalanche.

Steel. Aluminum. Gunpowder. Rubber. Wood. Brass. Flesh and bone.

It buried the Axis powers under numbers so large they stopped being numbers and became something else.

A river of metal flowing to every theater, every front, every battlefield.

The men who fired the guns and drove the tanks got the headlines, and they deserved them.

But behind every pull of a trigger, there was a factory whistle.

Behind every shot down, every tank destroyed, every road marched, there was a woman like Sarah, holding a cartridge up to the light and sending it down the line.

Behind every victory, there were twelve billion small, half-inch-wide reasons why the Axis was doomed the moment America decided that being an arsenal of democracy wasn’t a speech.

It was a promise.

News

CH2. They Mocked His ‘Cheap’ Machine Gun — Until John Basilone Stopped 3,000 Soldiers With it

They Mocked His ‘Cheap’ Machine Gun — Until John Basilone Stopped 3,000 Soldiers With It The darkness over Guadalcanal on…

CH2. They Laughed at His ‘Mail-Order’ Rifle — Until He Killed 22 Japanese Snipers in 7 Days

They Laughed at His “Mail-Order” Rifle — Until He Killed 22 Japanese Snipers in 7 Days January 22nd, 1943. Guadalcanal,…

CH2. A Submarine Drone Just Found a Sealed Chamber in the Bismarck — And Something Inside Is Still Active

The first thing they saw was the heat. At nearly five thousand meters down, there wasn’t supposed to be any….

CH2. Japan Laughed at America’s “Toy Bomb” Then the Ocean Turned Into Fire

Japan Laughed at America’s “Toy Bomb” Then the Ocean Turned Into Fire It began with laughter. Not the warm, human…

CH2. US Navy Wiped Out Japan’s Fleet in 40 Minutes

US Navy Wiped Out Japan’s Fleet in 40 Minutes The men on Yamashiro could not see their enemy. They could,…

CH2. Germans Couldn’t Believe One “Fisherman” Destroyed 6 U-Boats — Rowing a Wooden Boat

Germans Couldn’t Believe One “Fisherman” Destroyed 6 U-Boats — Rowing a Wooden Boat May 17th, 1943. North Atlantic dawn. The…

End of content

No more pages to load