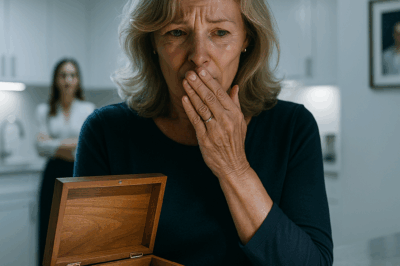

Ten Days Before Thanksgiving, I Discovered Something That Shattered My Heart — My Own Daughter Was Plotting to Humiliate Me in Front of Our Entire Family

Part I — The Script They Wrote Without Me

I found out by accident.

Not because I snooped, not because I was looking for proof that my daughter loved money more than she loved me, but because the family group chat started lighting up while my phone sat on the arm of my recliner and I was too slow to mute it. My thumb brushed the screen. A message popped open. A thread I wasn’t supposed to see slid into view.

Clare: We’ll do it after dessert. I’ll hand him the envelope, Kyle will say something like, “It’s time to let the next generation flourish,” and everyone will clap. It’ll be perfect for the video.

Mom: Make sure you sit him at the head of the table. We need him centered for the photos.

Kyle: Got the transfer forms printed. He won’t say no in front of everyone.

Clare: Don’t worry. Dad always says “family helps family.” He’ll do it. He always does.

I stared until the words blurred. Not because of age, not because of the cataract the doctor keeps telling me to schedule, but because something inside me went very, very still.

I put my phone down, and for a long minute I did nothing except listen to the quiet. The house creaked the way old houses do when the heat kicks on. Somewhere outside, a neighbor’s wind chime shivered in the late autumn air. The clock on the wall ticked a little too loud. That was the only sound inside me, too—ticking. Counting down.

I told myself I could be reading it wrong. That perhaps they were planning a harmless bit of theater for the sake of “memories.” That the envelope might be a handwritten letter, or a photo. But you don’t print out transfer forms for a photo opportunity. You don’t script applause for a moment of tenderness. You don’t say he won’t say no in front of everyone if you aren’t planning a public coercion.

Ten days before Thanksgiving, I learned my only child—my Clare, my little girl who used to run into my arms after school with drawings smudged with crayon—was planning to turn me into a prop. Not a father. A stage.

I didn’t confront her. Not right away. Rage scrambles the tongue; I wanted my words.

Instead, I did the thing that’s kept me alive through grief and factory layoffs and the kind of lonely no one writes songs about: I made a list. That list had two columns.

Column A: What they think I’ll do.

Column B: What I’ll actually do.

Under Column A, I wrote: Smile. Get misty. Say “of course.” Sign. Under Column B, I wrote: Stay seated. Breathe. Ask questions. Say no.

I put the list in my pocket and carried it like a talisman. Not against them, but against myself—the version of me who believes love is a receipt you hand over whenever someone says “family.”

The next ten days foamed with the kind of activity Clare loves. Finalizing menu options. Seating charts. Coordinated sweaters for photos. She texted me a reminder not to bring a store-bought pie this year because we’re keeping things elevated, Dad. I said all right because I have learned how to save my breath for the moment it matters.

What I didn’t tell them was that I had already had one moment like this—my Christmas—with that envelope. It had come dressed up as a gift and it had almost broken me. This time I saw the trick coming like weather.

What I also didn’t tell them was that I had worked too many double shifts, peeled too many ruined shingles off roofs in February snow, and sold the house where their mother died to pay tuition bills to be surprised by the cost of a so-called favor. I did not get to this age by believing strangers. I was not going to finish it by believing my own child when she says the word family and means fund.

And still—because I am her father, because there is no bone in my body that doesn’t know the weight of her in a car seat while her mother’s funeral flowers dried over the sink—part of me hoped I was wrong. That she’d set the script aside and hand me a real note instead. That she’d say I love you without printing anything.

Hope will embarrass you if you let it.

Part II — The Chair at the Head of the Table

The house smelled like turkey and rosemary and the cleaner my mother used to swear by that Clare now orders in bulk because it looks good in photos. The twins ran through the foyer screaming with joy because they are five and screaming is how joy escapes them. Kyle adjusted his cuffs like the camera had already arrived. Clare kissed my cheek and called me her guy the way she does when she needs something bigger than salt passed down the table.

I took my seat at the head, as instructed. There was a printed card with my name in a calligraphic font. The place setting gleamed. The chair felt like a throne or a trap depending on how long I sat in it.

Dinner tasted like it always does when you’ve been relegated to the role of audience in a life you once starred in—salt and memory. People passed plates and jokes back and forth over my lap as if I were a coffee table with elbows. I smiled when it was polite to smile. I told the story about the year their mother overcooked the rolls and I pretended to love them because that is the currency of nostalgia. And I waited.

It came with the pie.

Clare stood and tapped her glass with a spoon. The room tilted toward her because she’s got that brightness some people are born with—the kind that makes you feel like a lamp is being turned in your direction whether or not you asked for light. Kyle placed an envelope in her hand. I watched Mom’s fingers tremble with anticipation. Someone turned the music down.

“Dad,” Clare began, smile already damp around the edges. “No one has done more for this family than you. You’ve always said family helps family—”

“I have,” I said, beaming the words back at her like a mirror.

“And we want to give you the chance to do it again,” she said, and for a second the room didn’t know whether to clap. Then they did.

She put the envelope in my palm and leaned down like she was kissing my forehead. It was a stage whisper. “Say yes, Dad.”

I opened it.

No surprises. Forms. Balances. $60,000 in loans attached to a man whose handshake has never included eye contact.

I lifted my head. People mistook the movement for emotion. I could feel the room lean to catch tears. I didn’t offer them any.

“Clare,” I said, and my voice sounded like mine—steady, not soft—“what is this?”

Her smile wobbled. “It’s… well, you know Kyle’s business—”

“No,” I said gently. “I asked what this is.”

She faltered. Kyle recovered with a laugh designed to feel collegial. “It’s just a formality, sir. We transfer it to your name. You have better rates. It’s temporary. The optics are good for my credit.”

“The optics,” I repeated. “For your credit.”

Clare put a hand on my shoulder. “Dad, please. This will mean everything to us.”

“And what will it mean to me?” I asked.

Silence is a kind of mathematics. It adds weight to every word that follows. I let it accumulate until even the twins knew not to drop a fork.

My list burned in my pocket, Column B warm against my thigh.

“I’m not signing,” I said. No apology. No explanation.

Clare blinked as if someone had flashed a camera in her eyes. “But—”

“No.”

“Dad,” she said, voice tightening. “You have savings.”

“I do,” I said. “And I have plans for them.”

Her face did a thing then—a muscle I’d seen only once before when she was twelve and realized the goldfish she forgot to feed was not sleeping. She looked not angry but offended by reality.

Kyle cleared his throat again because that is more of a habit than a need with him. “We can discuss this privately later.”

“We are not moving it to later,” I said. “We are moving it to never.”

A sound somewhere between a scoff and a sob skittered across the table from my mother’s end. “After everything we’ve done,” she murmured into her napkin.

I let that one go. The ledger of my life is not a thing to open in front of grandchildren.

We ate dessert. It tasted like cinnamon and something turning. The room tried very hard to restart conversation in another part of the engine. Laughter came out stalling. The twins asked for more whipped cream and didn’t notice the ice.

They left early—Clare and Kyle—in a storm of polite, tight smiles. “We’ll talk later,” she said in the entryway. “You won’t feel this way in the morning.”

“I’ll help you with the dishes,” I told my mother. I dried plates until my knuckles ached and she stopped trying to scold me with silence.

When the house had finally remembered how to be quiet, I sat by the fire with that envelope closed again and thought about all the times I had said family helps family and meant I help you; you let me love you. I thought about my wife, who would have reminded Clare that you don’t ask a favor with a camera rolling. And I thought about Christmas and the envelope that had changed the taste of the holiday in my mouth for a year.

This time, I had said no while it still mattered.

The text from Clare came just before midnight.

You humiliated me in front of everyone. On Thanksgiving.

I stared at it until the words separated from meaning. Then I typed back, You scripted my humiliation. I interrupted your rehearsal.

She didn’t reply. That is a thing we have in common.

Part III — An Empty Envelope and a Full Booth

You can love a person and still refuse the bill when they hand you someone else’s tab.

Ten days after Thanksgiving became ten days of silence. I fixed a leaky faucet. I shoveled the first clean snow off the porch. I called my friend Tom to borrow his hedge trimmer and he asked if I was doing all right and I said yes because I had said no and the two together felt like breathing after a long time underwater.

I expected rage. What I got was Christmas and an envelope dressed up like forgiveness.

“Merry Christmas, Dad,” Clare said, bright as a lit tree on a dark street, holding out white paper like a dove. “This will mean the world to us.”

I peeled it open and there it was again—debt wearing my name like a coat it hadn’t earned. A note at the bottom in my daughter’s careful handwriting: Dad, we know you have savings. This would mean everything to us. Kyle hovered behind her, hands in his pockets, eyes watching the room the way raccoons watch a deck.

“I won’t be your bank,” I said. My voice sounded like the hinge on a door that’s been oiled. It moved without noise now.

They left soon after. Mutters about selfishness trailed behind them like perfume.

A week later I got the call about Kyle, not from them but from a woman at the bank who spoke in paragraphs meant for strangers.

Then a week after that I got the diner call. “Sir, there’s a young woman here asking for you. Says she’s your daughter.”

The bell on the door chimed that little silver sound from my childhood when you walked into the drugstore for a Coke. Clare sat in a booth she didn’t belong to. Her face looked ten years younger, which is what happens to adults when fear strips them of pride. She stood before I reached the table, then sat hard like standing was a mistake she couldn’t afford.

“I didn’t know he’d do it,” she said, voice already a ruin. “After Christmas he took out more loans. He said he had a plan. Then he disappeared. He left me with everything.”

I looked at her hands. She’d chewed one cuticle raw. I remembered those hands on construction paper turkeys when she was five. There are people who will call me foolish for what I did next. That’s all right. They haven’t watched their child breathe through grief.

“You start by facing it,” I said. “Not with my savings. With your hands.”

She cried, not prettily, which is how you know a person means it. She moved back in with me, not as a dependent, not as a princess, but as a woman holding a broom. I cooked simple food and made sure she ate it. She got a job at the bakery up the road, the one that smells like sugar even in July. She brought home a spiral notebook and sat at the table I built with her mother and whispered numbers to herself the way you whisper prayers you wish you’d learned earlier.

I did not bail her out. I did not sign things. I did not attend meetings with her like a suit on a hanger. I said no every time she asked for money and yes every time she asked for time or wisdom or a ride to a place where a person could explain a form without lying. Some nights she went to bed crying from the kind of exhaustion that feels like loneliness. I sat in the kitchen with the light on and drank lukewarm tea and kept the house quiet for her.

One night I walked in and she looked up, eyes puffy, and smiled a little. “Dad,” she said, “I think I’m finally learning.”

“That’s all I ever wanted,” I said.

A year later, in the same booth at the same diner, she handed me an envelope. Because life is an echo chamber and sometimes the thing that breaks you also becomes the thing that fixes you.

“Merry Christmas, Dad,” she said. There was a check for five hundred dollars inside. It could have been five and the love would have weighed the same.

“It’s not much,” she said, cheeks coloring. “But it’s the first time I can give you something that wasn’t stolen from you.”

“You already have,” I said, and we both knew I didn’t mean the money.

Part IV — The Cost of a Seat at the Table

Here’s the thing I learned on the long walk from that kitchen chair to the diner booth: control doesn’t age well. It cracks like paint on a porch swing because it’s been in the weather too long. The people who wield it mistake volume for stability. They mistake your silence for consent. They think love is a layaway plan.

It isn’t.

Ten days before Thanksgiving, I discovered the playbook. On Thanksgiving, I closed it and set it gently on the table. At Christmas, they wrapped it and handed it back to me. On a Tuesday in February, my daughter handed me something else—accountability—and it was the most beautiful thing I’d ever opened.

People ask me if I spoke to Clare about those messages. The ones about applause. About how she wrote he won’t say no in front of everyone with the confidence of a child describing gravity. I didn’t. Not directly. Because here is the truest thing I know about people who grow up loved and about people who grow up trying to earn it: we learn with our hands more than with our ears. Consequences are the only arguments that stick. A year of her own ledger taught her what my lecture could not.

I did tell her this: “If you ever love someone who tries to turn your generosity into an invoice, say no. If they say you’re ungrateful, smile. If they say family, ask them to define it. If they define it as what you owe them, start walking.”

Sometimes love is a check you don’t cash. Sometimes it’s a meal you do eat. Sometimes it’s time at a table with no cameras where the only applause comes from two hands clapping for the small miracle of a person who almost drowned learning to float.

I still keep a list in my pocket. The columns have changed.

Column A: What I can carry.

Column B: What I won’t.

Under A I write soup, stories, an extra chair. Under B I write debt, shame, applause.

On my birthday this year, I made pancakes. The cheap kind you only need to add water to, the ones my wife used to hate because she preferred everything from scratch. I flipped them badly and laughed at myself because there is no one left to impress. Clare came over after her early shift with a ribbon in her hair that made her look like she did when she was ten. She pretended not to notice that I’d burned the first batch. I pretended not to notice that she’d brought an envelope. We are still us.

It wasn’t money. It was an old photo she found that I hadn’t seen since before I knew how to replace a water heater without turning off the main. It was the three of us on a blanket in a park—her mother laughing, Clare mid-scream, me startled. No one was asking for anything except more sun.

We ate badly cooked pancakes. We told a story we’ll correct next time we tell it. After she left, I put the photo in a frame on the mantle where the envelope used to sit in my memory like a weight. The photo felt lighter. I slept that night without my list.

Ten days before Thanksgiving, I found out my daughter had written a script where I was the applause machine. I didn’t show up for the performance. I showed up for the person holding the pen.

If this is you—if your chair at the head of the table comes with a teleprompter—you can choose a different sentence. The first word is no. The second word is still. The third word is love—not the kind that empties your pockets and calls you selfish for what’s left, but the kind that holds a hand in a diner and says, Start here. I’ll keep the light on.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. My parents treated me like a maid, until at my grandfather’s funeral…

My parents treated me like a maid, until at my grandfather’s funeral… Part I — The Smallest Room My mother…

CH2. At Dinner, She Smirked: “My Ex Just Texted – I’m Meeting Him For ‘Closure’ Tomorrow.” I Just Nodded: “That’s Thoughtful.” The Next Morning, Her Bags Were Professionally Packed, The Locks Changed, And A Moving Truck Waiting. When She Came Back From Her “Closure” Meeting… She Realized I’d Already Closed Everything…..

At Dinner, She Smirked: “My Ex Just Texted — I’m Meeting Him for ‘Closure’ Tomorrow.” I Just Nodded: “That’s Thoughtful.”…

CH2. Parents Told Me, “Skip Thanksgiving — We Need Space.” But Their Regret Came Quickly

Parents Told Me, “Skip Thanksgiving — We Need Space.” But Their Regret Came Quickly Part I — The Message The…

CH2. My Daughter Betrayed Me… But My Late Husband Saved Me

My Daughter Betrayed Me… But My Late Husband Saved Me My daughter thought she could take everything—my beach house, my…

CH2. My Family Skipped My Child’s Surgery, Then Demanded $5,000 — and Called the Bank When I Laughed…

My Family Skipped My Child’s Surgery, Then Demanded $5,000 — and Called the Bank When I Laughed… Part I —…

CH2. The Family Of My Daughter-In-Law Pushed My Grandson Into The Lake… But They Didn’t Know My Brother

The Family Of My Daughter-In-Law Pushed My Grandson Into The Lake… But They Didn’t Know My Brother Part I —…

End of content

No more pages to load