Sister Announced, “You’re Evicted,” At Dinner, While Her Kids Planned Pool Parties In Our Garden…

Part I

The house looked like a postcard someone forgot to put back in its sleeve—Queen Anne gables, a turret with a window seat, brick chimneys ribbed like old knuckles, and out back a walled garden that felt stolen from another century. When I signed the stack of closing documents two years ago—my company on every page as purchaser, my pen steady as if it had always known this moment would come—I walked through each empty room and said out loud, “Welcome home.”

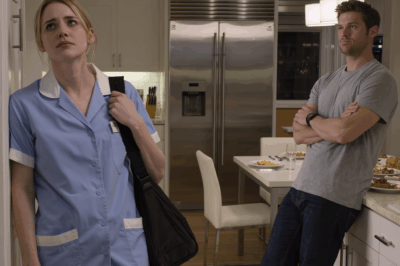

I kept the third floor for myself and for Meridian Solutions—my corporate restructuring firm, quiet work that often required brutal honesty and always required discretion. The second and first floors, with their carved mantels and pocket doors, I offered to my sister, Nicole, and her family “for a few months” while they figured out where they wanted to live. A bridge, not a destination. The kids were eight, ten, and fourteen; bridges are mercy when school years are measured in friendships and bus routes.

Months calcified into two years.

We built a routine with separate doors. They used the front steps, all crown moldings and a brass knocker that caught afternoon light; I used the side door off the alley, key ready between second and third knuckles, coffee balanced on a stack of binders. We split the garden by understanding, not by fence: my morning herb pots in the sun by the gate; their evening lanterns near the old quince tree. Over time, Nicole’s string lights began a slow annexation, and a fire pit arrived one weekend with the potential of smores used as justification.

On Sunday afternoon my phone flashed: Family dinner. Mom’s coming. We need to talk about the house situation. I slid the text into my mental file marked “brace.” Nicole’s “we need to talk” had a way of meaning “we’ve talked and decided.”

I arrived at six with a bottle of Barbera and the kind of patience that looks like a smile. Mom had already assumed the head of Nicole’s dining table, wearing the neutral cardigan she believes lends gravity. Brian poured wine with the wrist roll of a man who reads restaurant blogs. The three kids said hello in the way teenagers do, barely looking up, promising to circle back to eye contact at some future date.

“Anna,” Nicole said, voice pitched at managerial. “Have a seat.”

We tiptoed through small talk until Nicole set down her fork like a gavel. “We need to discuss the living situation.”

“What about it?” I asked.

“This house isn’t working,” she said, and smiled in the way people do when they think they are being valiant. “The kids need more space. Madison starts high school in the fall; she needs her own room. The boys are sharing and fighting. And you’re taking up an entire floor.”

“I live here,” I said, not angry, just clarifying “gravity” for someone pointing at the sky and calling it negotiable.

“But do you need all that space?” Nicole pressed. “You’re one person. We’re a family of five.”

Mom nodded with the solemnity of a judge who forgot the law and remembered only the chorus. “Anna’s always been selfish about space.”

Brian chimed in. “We’ve been looking at houses, but the market is impossible. Everything decent is in the suburbs.”

“The suburbs are nice,” Mom offered, as if this were a balm.

“We don’t want suburbs,” Nicole said, steel under velvet. “Our life is here. This house is perfect for a growing family. Here’s what we’re thinking. You move out, find an apartment in the suburbs. We’ll take over the whole house. It makes sense.”

“We’re a family,” Mom added, performing a chord they’d rehearsed. “You’re single. You don’t need this space.”

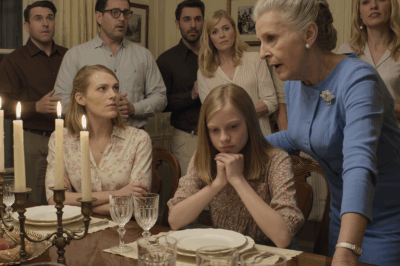

Madison, who had learned timing from adults, piped up. “When Aunt Anna moves out, can I have the third floor? It has the best windows.”

“We’ll see,” Nicole said, then to the boys, “No skateboards upstairs.” The youngest raised his hand like this was civics. “Can we get a pool in the garden? Above ground at least?”

I put my glass down. “You’re asking me to move out.”

“We’re telling you,” Nicole corrected. “You’re evicted.”

The word hung in the air like a joke said too loudly. “We’ve been patient for two years,” she went on. “Our family is growing and your lifestyle isn’t compatible anymore.”

“My lifestyle.”

“You’re never here,” she said with the confidence of the uninformed. “Always traveling or locked in your office. You don’t contribute to the household. You don’t help with the kids. You’re basically a ghost who happens to pay some bills.”

“I pay bills,” I repeated, not as defense but as an inventory.

“Well,” Brian said with a shrug that wanted to be magnanimous. “We appreciate that, but that’s not enough anymore. We need the space more than you do.”

Mom patted Nicole’s hand. “You’re being very reasonable. Anna needs to understand family comes first. She’s had two years here. That’s generous.”

“When do you want me out?” I asked.

Nicole looked at Brian the way co-captains pretend they haven’t already planned the route. “End of the month,” she said. “Three weeks. Plenty of time to find a place.”

“End of the month,” I repeated. The kids were openly excited now, sketching futures in the air with words. Media room. Pool parties. Movie marathons. The third floor as prize, not home.

The doorbell rang.

Brian went to answer it. A professional voice carried from the hall. “Hello, I’m looking for Nicole Morrison. Sarah Chen from Parkside Realty.”

Nicole’s face brightened. “Oh, you’re early,” she called. “I thought we said seven.”

A woman with a calm smile and a tablet appeared in the doorway—and paused when she saw me. “Ms. Hayes,” she said. “I didn’t realize you’d be here.”

“You know each other?” Nicole blinked.

“Ms. Hayes is my client,” Sarah said.

“Your client?” Nicole frowned. “I called you about listing this property. I’m the one who lives here.”

“Lives here,” Sarah repeated, eyes flicking to me.

I stood slowly. “Nicole, why did you call a real estate agent to list the house?”

“Obviously,” she said, “once you’re out, we’re going to sell it. The market’s hot. We can use the equity to buy something bigger. Something actually ours.”

“Something actually yours,” I said, and let the words sit between us like an exhibit.

“It’s in the family trust,” Nicole added too quickly. “Dad set it up before he died.”

“Dad’s trust owned the rental in the suburbs,” I said. “Worth maybe two hundred thousand. It was divided equally after probate. You got your hundred. I got mine. This house has nothing to do with Dad’s estate.”

“You said—”

“I said I had property available,” I said. “I never said it was family property.”

“There is no trust tied to this address,” Sarah said gently, scrolling. “This property is owned by Meridian Solutions.” She glanced up. “Ms. Hayes’s firm.”

Brian stared. “This… can’t be right.”

“It’s absolutely right,” Sarah said. “I handled the purchase. Meridian Solutions is the sole owner. And Ms. Hayes is the sole owner of Meridian Solutions.”

Nicole grabbed the documents from my hand. “You’re lying. You can’t afford this house. It’s worth—” She looked at Sarah.

“About 1.1, given the garden,” Sarah said, businesslike.

“You don’t have that kind of money,” Nicole said to me, the certainty now desperate. “You work from home. Consulting. That’s not real money. That’s not million-dollar-house money.”

“Meridian grossed 3.2 last year,” I said. “Seventeen clients on retainer. Forty-three projects closed in two years. My fee is twenty thousand per project plus a percentage of savings. Net after expenses and taxes is around eight hundred. The mortgage is four. Property tax is eighteen annually. Insurance, utilities, maintenance through the company because this is my primary office.”

Brian’s mouth shaped an oh that never landed. Mom stared at her wine as if numbers floated up from it like mystic sediment.

“You live on the third floor,” Nicole said weakly. “You dress like you drive a Honda.”

“I don’t act like I need to prove I have money,” I said. “There’s a difference.”

Mom found her voice. “If you own this house,” she said softly, “why didn’t you tell us?”

“Would it have changed how you spoke to me tonight?” I asked. “Would you have said ‘suburbs are more your level’? Would you have told me to leave in three weeks? Or would you have smiled more and asked for a loan?”

Silence said the quiet part.

“You let us live here,” Nicole said, smaller. “Why?”

“Because you needed help,” I said. “Because I had space. I thought coexistence was possible.”

“But you were going to kick us out eventually.”

“I was letting you stay until you found your footing,” I said. “Tonight, you announced you were evicting me from my own property, called my agent to sell my house, and planned pool parties in my garden.”

“For the record,” Sarah said gently to the room, “I came because Mrs. Morrison called and said the owner was moving out and she wanted to discuss listing options. I had no idea she intended to evict…the actual owner.”

“What happens now?” Brian asked, voice careful as if the right tone could unspill a glass.

I looked at Sarah. “Timeline for vacant possession?”

“In this city,” she said, “sixty days’ notice is standard for tenants. Given there’s no lease and you’ve been occupants by permission, it’s murkier. A judge might grant extra time due to children, but there’s no automatic right.”

Nicole’s head snapped up. “You’re evicting us,” she whispered. “After—”

“After you evicted me at dinner,” I said. “Yes.”

“Family doesn’t evict family,” Mom said, outraged finally.

“Family doesn’t treat family like a placeholder for their wish list,” I said. “Family doesn’t sell houses they don’t own.”

I watched my nieces and nephew. Madison’s face was red, wet. The boys looked at their hands as if answers might appear there if they waited. “I’ll give you ninety days,” I said, and everyone exhaled. “Three months to find a place. I’ll cover this month’s utilities. After that, you’re responsible until you vacate. Starting now, the garden is off limits.”

“Where will we go?” Nicole asked.

“You said the suburbs are nice,” I said softly. “More space. Better schools. More your level.”

Sarah gathered her tablet. “I’ll email you market analysis tomorrow, Ms. Hayes,” she said to me. “For when you’re ready.”

After she left, the table breathed like it had been holding breath for years. Brian stood. “I need to make calls,” he said, then fled. Mom stared at me like I’d turned into a stranger who owed her a biography. Nicole cried, the quiet kind that has nothing to do with regret and everything to do with loss.

I stood. “I’m going back upstairs,” I said, “to my floor, my office, in my house. Ninety days.”

On the stairs, I paused and looked through the tall window at the garden—string lights swagged like entitlement, the fire pit dark and still smelling faintly of smoke. Tomorrow I’d have it all cleared.

Part II

The morning after dinner, I drafted a formal notice while coffee cooled beside my keyboard. Precision protects peace. My lawyer, Cora, reviewed it, made two edits, and sent it back with a note: You’re being more generous than the law requires. It’s often the difference between a story that ends and one that escalates. Good call.

I printed two copies, addressed envelopes, and walked them to the mailbox on the corner. When I pushed the red flag up, a wave of something like grief and relief combined hit me hard enough to blur the old brick across the street. You can mourn a fantasy and still be glad it’s over.

Downstairs, movers took the fire pit apart and stacked chairs that had cost more than they should. The kids watched through the window, faces stiff. When the younger boy stomped away, Madison lingered.

“Can I ask a question?” she said, hesitating, body still half turned toward flight.

“Sure,” I said.

“Why didn’t you tell us? About the house. About the job.”

“Because telling people how you pay your bills is rarely an invitation to respect,” I said. “It’s an invitation to comment. I’ve spent a long time being who I am without requiring witnesses.”

She nodded slowly. “Mom thought you were…” She stopped. “Different.”

“Your mom is allowed to think whatever she wants,” I said. “She isn’t allowed to take what isn’t hers.”

“Are you mad at us?” she asked, small.

“I’m mad about a lot of things,” I said. “Not at you.”

When she left, I sat in the garden for the first time in months. It smelled like damp brick and rosemary. Sirens in the distance braided with birds. There’s a sound to a decision settling; it’s similar to rain through leaves.

By week’s end Brian had moved their SUV into recruitment mode. Listings printed, map apps open, calls taken in the foyer at odd hours. Nicole’s Instagram went quiet except for reposted quote cards about perseverance. Mom alternated between calling me by my full name (indignation) and my childhood nickname (strategy).

On day ten, a letter appeared under my door in Mom’s handwriting. The loops of her Ls looked like a woman who had always been proud of her penmanship. “Anna,” it began, “We’re family. This is too extreme. Your sister has children. You’re being unreasonable.”

I replied with a copy of the notice, a paragraph underlined: Occupancy has been permissive. Permission has been withdrawn. You have ninety days from the original date. It felt cold, which is sometimes a synonym for fair.

Cora called. “Do you want me to be the bad guy?” she asked. “It’s what I’m for.”

“I’m fine,” I said. “They know where the line is now. That’s most of it.”

Work filled the spaces outrage used to occupy. Two clients cried in my office that month—one CEO because he hadn’t realized how close he’d come to losing everything, one founder because she couldn’t believe she’d been allowed to keep her people. My job is to move money around until it behaves and tell the truth in a way people can afford to hear. I slept like someone who put heavy boxes down.

Part III

In week five, a flyer for an above-ground pool coupon ended up in our mailbox by mistake. Nicole had circled one in pink pen months ago when it appeared in the mail, planning a summer she didn’t own. I pinned it to the cork board in my kitchen, not as spite, but as a reminder of the narrative they told their kids: that space is something you deserve in proportion to your desire for it.

Mom started a campaign of nostalgia. “Remember when you wanted a pink bike and your father drove across town?” she texted. “Remember the biscuits your grandmother made?” Memory is not a currency; you can’t tender it in lieu of rent.

Brian came to my office one evening, hat in hand without an actual hat, and said, “I shouldn’t have let it get that far at dinner.” He looked like a man who wanted me to say, “All is forgiven,” so he could go home relieved and unchanged.

“You could have said something,” I replied. “You could have been the person who didn’t let it get that far.”

He nodded, chastened, eyes flicking to the framed diplomas he’d never asked about. “The kids will miss the garden,” he said finally.

“The garden will still be here,” I said. “You won’t.”

By week eight they’d put a deposit on a rental outside the city with a backyard the boys could destroy at will and a school Madison declared “maybe fine.” Nicole didn’t tell me herself; I heard it from the kids, who were giddy about stairs they didn’t have to share.

The night before the movers came, Nicole knocked on my office door. She looked tired and also annoyed with herself for looking tired.

“Three things,” she said, holding up fingers. “One, I’m sorry I said you were evicted. It was cruel. Two, I called your agent because I wanted to sell a house I told myself was mine. That was wrong. Three, I didn’t know what you did for a living. That’s on me, but you didn’t make it easy to know you.”

“I’m private,” I said.

She nodded. “You’re private. I’m—” She gestured at herself. “Not.”

“You also tend to fill in blanks with whatever suits you,” I said, neutral as math.

She grimaced. “Fair.”

“Teach the kids something different,” I added. “That’s the only bridge left worth building.”

She stared at me for a long beat, then nodded and left. It wasn’t reconciliation. It was recognition. It was also enough.

On move-out day, the house felt lighter, emptier in the way lungs feel when they remember how to take a deep breath. The kids hugged me in quick bursts that smelled like shampoo and hope. Mom refused to say goodbye, which is a kind of goodbye all its own. Brian shook my hand, a small act that meant more than any apology he had not found words for.

When the truck pulled away, I walked the three floors slowly. The second-floor parlor had an imprint on the rug where their couch had been; sunlight fell across it like forgiveness that didn’t require an audience. On the first floor, Nicole’s “Live Laugh Love” sign had left two nail holes. I didn’t consider spackling them. They felt like truth dots.

Part IV

I gave myself thirty days to decide whether to sell or to occupy. Sarah sent me comps, and Cora drafted a clean listing agreement just in case. In the quiet, I learned the answer: I wanted the whole house. Not to fill rooms with proof. To live in them.

I turned the first-floor dining room into a long library with a table that seated twelve and shelves made from old heart pine that glowed under oil like it had forgiven us for cutting it down a hundred years ago. I left the kitchen as it was, the only room where Nicole had shown good taste—white tile that refused to be trendy, brass fixtures that would forget fingerprints. I made the second-floor front room my music space and brought up a piano I’d been paying storage fees for since grad school because I told myself I didn’t have time.

I hosted dinner for the first time in a decade—a stew that required patience, a salad that didn’t, bread that cracked when you tore it. At the table sat people who had never asked how much the house cost; they asked how I wanted to live in it. We ate late and sat later. Someone washed dishes without being asked. Someone else swept the floor while humming. I looked around and thought: a house isn’t a lesson to teach other people about you; it’s a place to be exactly yourself.

On a Tuesday afternoon a month later, I walked out into the garden with a mug of mint tea and planted a small maple where the above-ground pool might have gone if I hadn’t been home—red leaves like a polite refusal. When I finished, I sat on the step and texted Sarah: Not listing. Keep me in mind for the building next door if it ever comes up.

She replied with a heart and a thumbs-up and, later, a photo of a storefront a block away that would be perfect for a client. Business and life braided neatly.

Mom called once from an unknown number. I let it go to voicemail. “I drove by,” she said, voice thinner but still convinced of a world arranged around her. “You’ve planted a tree. It’s pretty.” I saved the message and didn’t return the call. Beauty isn’t a bargaining chip either.

In spring, Madison sent me a photo from her new school’s spring fair—her journalism club with a banner they’d designed themselves, boys behind her red-faced from a tug-of-war they were losing and laughing anyway. “It’s okay here,” she wrote. “We’re okay.” I sent back a picture of the maple unfurling leaves like tiny hands and wrote: Good. Keep going.

Some nights, after I turn off the lights and start up the stairs, I pause at the landing where Nicole announced my eviction and listen to the house breathe. It sounds like what it is: old wood shifting; pipes settling; a home returning slowly, stubbornly, to the shape it was promised.

I used to think the only way to win a story like ours was to shout the ending. That night at dinner, Nicole did the shouting for both of us. “You’re evicted,” she said, the word snapping like a cheap flag. Weeks later, I answered in a way no one in my family ever taught me was an option: with paper, with boundaries, with three months of grace and a future that didn’t require witnesses to count as real.

They planned pool parties in a garden they didn’t own. I planted a tree.

They announced my eviction. I stayed home.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. HOA Karen Called the FBI to Crash My Wedding — She Had No Idea Who My Father Was!

When I said, “I do,” I never thought I’d be facing off with the HOA and the FBI at the…

CH2. My Husband Said Coldly: “You’re An Adult, Cook For Yourself. I’m Not Running A…

My Husband Said Coldly: “You’re An Adult, Cook For Yourself. I’m Not Running A Restaurant.” When I Came Home Starving…

CH2. My Sister Said, “We Didn’t Order For Your Son,” While Her Kids Ate $100 Meals — And I Froze.

My Sister Said, “We Didn’t Order For Your Son,” While Her Kids Ate $100 Meals — And I Froze. …

CH2. During a Family Dinner, My Sister Insulted My Daughter—Then My Mother’s Act Shocked Everyone…

During a Family Dinner, My Sister Insulted My Daughter—Then My Mother’s Act Shocked Everyone… Part I — The Return…

CH2. My brother snarled, “You’re a bastard,” then tossed a chewed bone onto my daughter’s plate.

My brother snarled, “You’re a bastard,” then tossed a chewed bone onto my daughter’s plate. Part I I’m Diane Larson,…

CH2. Karen Took a Handicapped Spot Without Permit – What the Cop Did Next Shocked Everyone

Karen Took a Handicapped Spot Without Permit – What the Cop Did Next Shocked Everyone Part I It was…

End of content

No more pages to load