She Handed Me A List Of Chores And Said, “Do These Or I’m Leaving.” I Just Looked At Her…

Part I — Exile

“Go sleep on the street,” she said.

No tremor, no heat. Just a door slamming in the middle of a sentence. I stared at Hannah, then at the suitcase I hadn’t noticed by the door. She’d already packed it: my clothes folded with the same precision she reserved for malice, my toothbrush, even my phone charger—because cruelty is never complete without efficiency.

“I didn’t mean to forget,” I managed. “It was one dinner.”

“You never mean to,” she said, arms folded, the bracelet I’d bought her gleaming like a punchline. “That’s the problem. You never mean anything, but somehow you always disappoint me.”

“Where am I supposed to go?”

“Anywhere that’s not here.”

Seven years married. We used to argue about seasoning, not eviction. There’s a tone people use when they expect you to beg. It’s a test. I failed it. I picked up the suitcase and stepped outside into a night that smelled like wet asphalt and decisions.

The door’s click was too soft for what it meant. My phone buzzed. A text: Don’t come back tonight.

I walked. The streets offered up their lit windows like museum exhibits: couples washing dishes, a baby being bounced, a man in a chair with a book he was pretending to read because his mind was on something else. I watched my breath fog and reach for things it couldn’t hold.

“You okay out there?” a voice called from the corner. Clara stood on her porch in a cardigan, hair loose, a mug steaming in her hands. She was my neighbor—the kind who lent spices and waves, widowed two years, her tabby wandering the windowsill like a slow clock. She’d always been kind in the easy, nonintrusive way that made kindness feel like weather.

“Just needed air,” I lied.

“With a suitcase?” she asked gently.

I laughed and heard the bitterness scratch my throat. “Got kicked out. Guess I’m taking her advice and sleeping under the stars.”

Clara looked at the sky, then at me. “It’s going to rain,” she said. “I’ve got a spare bed.”

Pride likes to play savior at the worst times. “I’ll figure something out. Motel—”

“Don’t be ridiculous. Come on.” She held the door, kindness in one hand, cinnamon and old wood in the other. I stepped into a house that felt like a hot bath you didn’t know you’d needed. A towel appeared. “Dry off, warm up. I’ll make tea.”

In her kitchen, I told her the safest version of the truth: the argument, the suitcase, the text. Nothing about the rot that had been growing between the baseboards. Nothing about the way the word “sorry” had turned into a receipt in our house. Clara listened like listening was something she’d practiced.

“I always thought she was too proud for her own good,” she said finally.

“She’s not a bad person,” I said on instinct. The words tasted like something expired. “We’ve just been… off.”

“Off,” she repeated, rolling it between her teeth. “That’s one way to put it.”

There was something in her eyes I hadn’t noticed before. Warmth is dangerous when you haven’t seen it in a while. I changed the subject. “Thank you,” I said. “You didn’t have to.”

“I wanted to,” she said simply. “Nobody deserves to be out in the cold.”

I fell asleep in her spare room to the sound of old floorboards and the knowledge that somewhere across a thin wall a person existed who’d chosen to care.

Part II — The Empty House

Morning brought sunlight and the smell of eggs. Clara hummed badly in the kitchen. “Any word?” she asked, sliding a plate in my direction.

I checked my phone. Nothing. The silence wasn’t absence. It was punctuation.

“She’ll come around,” Clara said. “Or she won’t. Either way, maybe she’ll realize what she’s lost.”

I didn’t answer. I was afraid to admit that a small, ugly part of me hoped she wouldn’t. That part scared me more than the cold had.

By noon, I was back at the house. The door was unlocked. The air inside was antiseptic with perfume. The standards of open house smell. Only the mess that makes a home a home was missing. Drawers sit open differently when they’ve been emptied. Empty hangers clink in a particular despair.

An envelope sat on the dining table, my name like a dare. I opened it.

Sorry. I didn’t know how to tell you. It’s not about you. It’s about me. I’ve been unhappy for a long time. I met someone. It just happened. Please don’t look for me. It’s better this way.

People like to say there are no words for some moments. That letter is proof that there are too many.

I sat on the couch and let the museum of our life play its loop: her laughter, her touch, the way she used to whisper my name like it meant something. We always imagine the montage before the cut.

At dawn, I went outside because walls were starting to feel like opinions. Clara was watering her plants. She set down the can as if it were a fragile animal and walked toward me.

“She’s gone,” I said, and the words didn’t sound like words anymore.

Clara stepped closer. “Then stop chasing someone who doesn’t want to be caught.”

There was something knowing in her eyes. I looked at her too long. “Did you know?” I asked softly.

Her gaze flickered, a blink she didn’t expect me to catch. “Know what?” she asked, and the lie sat down between us and made itself comfortable.

“That she met someone?” I said.

Clara’s mouth opened and then decided against speech. She turned toward her door. “It’s cold again. Come inside.”

And in that breath—between her invitation and my refusal—I finally understood. She wasn’t just kind. She was also the reason my front door had stayed shut.

She was the bed my wife had found to be warm. The person who had offered me shelter had already taken my home.

Part III — The Watchlist

Grief makes your brain a detective, even if your heart begs to remain a tourist. The details reassembled themselves in high-definition: the way Hannah’s perfume had changed—the kind of vanilla that pretends to be innocence; the sweater Clara wore the day she told me “nobody deserves to be out in the cold,” a sweater I’d complimented in our hallway weeks earlier when my wife had left for Pilates smelling like it; Clara’s tabby cat lounging on our porch more often lately, as if told it had two houses.

“Why?” I asked the refrigerator. “Because,” it answered, humming its noncommittal devotion to temperature.

For days, I did as mechanical men do when pain arrives disguised as math: laundry, gym, work. The house cleaner’s Tuesday vacuum lines felt like punctuation. The silence felt less like absence and more like a room that had finally embodied its purpose.

Clara knocked on the third day, a Tupperware of lasagna in her hands like an apology. “For later,” she said. Behind her, her tabby blinked at me with the regal boredom of a creature who knows everything and judges nothing. Her eyes—Clara’s, not the cat’s—were careful.

“I know,” I said, because lies remove oxygen.

Her shoulders fell. “Hannah came over sometimes when you were late,” she admitted, the words groping their way into the air. “At first, it was just talking. Then she started staying. I’m not—” She lost the sentence in the middle and reached to find it again. “I didn’t plan it.”

“That’s the slogan for a lot of damage,” I said.

“She told me you forgot dinner,” Clara blurted, as if forgetting to eat should be enough to get you evicted. “She said you didn’t look at her anymore.”

The sudden need to laugh almost knocked me over. “I was looking at spreadsheets,” I said. “Building the life she claimed I forgot.”

“I know,” Clara whispered. “But she was so—” She pressed her lips together until they were white. “I’m not asking for forgiveness.”

“Good,” I said. “I don’t have it.”

She nodded once, twice, then turned back to her porch, the tabby looping her ankle like punctuation.

That night, I sat with the laminated list Hannah had left like a joke nobody got. I turned it over, wrote a different list.

1. Lawyer. (Christian’s card already on my desk from last year when Hannah announced we might need a postnup because “women need protection.”)

2. Finances. (Freeze joint lines, preserve evidence, move salary to a new account.)

3. Locks. (Walt the locksmith had a voice like a baritone and a bag full of new beginnings.)

4. Message. (Not a social media detonation. A letter.)

The next morning, Walt changed the locks. “Marriage?” he asked, casual as he worked.

“Rebranding,” I answered.

At noon, I sat at the same kitchen island where the laminate had tried to hand me a new life and wrote a letter. It wasn’t a demand. It was a statement. You asked me to sleep on the street. I won’t. The locks have been changed. Your belongings will be boxed for pickup with your attorney present. Forwarding address provided by counsel. Do not enter this property again without notice. I signed it like a contract.

I slid the letter under Clara’s door too. As kind as she had been, neighbor is a title that requires boundaries more than casseroles.

Then I walked next door, knocked, and handed her the envelope myself. “Nothing personal,” I said.

“It’s all personal,” she answered, and held the letter as if it might bite her.

Part IV — Street, Home

A week later, Hannah texted. I’m coming by to get my things. She arrived with her mother and a man I didn’t know. Doris’s performance began on the steps—hands, pearls, volume. “You’re a monster,” she said, because that’s the script people choose when their daughter’s misery needs a villain.

“Your daughter told me to sleep on the street,” I said. “So I moved the street.”

They boxed her life quietly, if not gracefully. The man with them was a mover, not a lover. Clara’s porch light turned on and stayed on for the entire hour; she stood inside with her cat pressed against the glass like a child at an aquarium.

When Hannah came to the door for the last time, she didn’t ask for forgiveness. She asked for the Dutch oven and the good mixing bowls—assets divided by memory. “Keep the bracelet,” I said, because pettiness is heavy and I had already lifted enough.

She blinked, confusion scrubbing at her anger. “Is this it?” she asked, as if a speech had been promised and I had failed to deliver.

“This is it,” I said.

The first night alone should have felt like a fall; it felt like a landing. The house exhaled. Tuesday’s vacuum lines looked like grace. I opened the good bourbon and poured one glass. I stood at the window and watched the neighborhood practice normal—dogs, recycling bins, laughter leaking from someone else’s open window.

Clara sat alone on her porch with a blanket. She didn’t look over. I didn’t wave. Some proximities need seasoning time.

Three months later, the divorce was inked into the world’s bureaucracy. Christian was right: survival, not victory. The house stayed mine; the car did too. Transitional support for Hannah for six months—reality is expensive. The joint accounts became relics. The laminated list now lives in a drawer under the takeout menus—a relic of a moment I refuse to relive but want to remember.

Clara and I became weather again—“morning,” “beautiful roses,” “did you get the mailer about the HOA?”—small talk with scaffolding. Once, she left a bag of lemons on my porch. I left a thank you note that said nothing about Hannah, about nights, about the way kindness can be a policy and a weapon. In time, her tabby resumed choosing our porch equally.

Sometimes people ask, would you have let her in if she knocked and said sorry? I don’t answer. Forgiveness isn’t a doorbell. It’s a code.

Months after, on a crisp evening that smelled like new beginnings, Clara knocked. She held a mug and a sentence. “I keep thinking about that night,” she said. “Not because I’m proud. Because I’m not. I’m sorry. And I wanted—” She exhaled. “I wanted to tell you before it becomes a movie in your head that never changes shape.”

“Thank you,” I said. It was the only sentence that mattered. She nodded and walked back across a strip of grass that knew more secrets than it wanted.

The story didn’t end with me moving in next door. It ended with me moving back into myself. The best revenge wasn’t slamming the door. It was buying a better lock and then gardening.

The other weekend, Walt came by to look at the back door, because men who install beginnings like to see if they’ve held. He asked about the house. I said it was finally learning how to be a home. He pointed at the yard. “Nice tomatoes,” he said.

“Stability,” I told him with a smile. “It grows.”

He laughed and left me with a new key and old advice: “Don’t give this one to anyone who makes you sleep on the street.”

“Deal,” I said.

As if on cue, a breeze lifted, carrying cinnamon from Clara’s kitchen and the sound of somebody else’s laughter. I stood there and let the night decide it wasn’t cold anymore.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

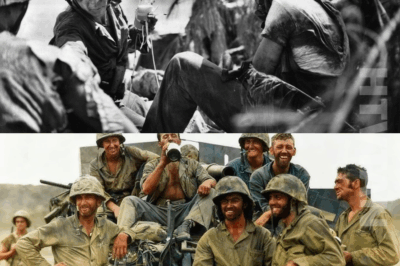

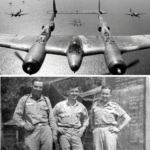

CH2. When Marines Needed a Hero, You’ll Never Guess Who Showed Up!

When Marines Needed a Hero, You’ll Never Guess Who Showed Up! Sunday, September 27, 1942. The jungle on Guadalcanal breathed….

CH2. This WW2 Story is so INSANE You’ll Think It’s Fiction!

Quentin Walsh was Coast Guard—but in WWII, he was handed Navy orders and sent behind enemy lines to capture a…

CH2. Making Bayonets Great Again — The Savage Legend of Lewis Millett

Making Bayonets Great Again — The Savage Legend of Lewis Millett The first time Captain Lewis Millett saw the Chinese…

CH2. 3 Americans Who Turned Back a 5,000 Man Banzai Charge!

3 Americans Who Turned Back a 5,000 Man Banzai Charge! Friday, July 7th, 1944. The night over Saipan was thick…

CH2. The Most Insane One-Man Stand You’ve Never Heard Of! Dwight “The Detroit Destroyer” Johnson

The Most Insane One-Man Stand You’ve Never Heard Of! Dwight “The Detroit Destroyer” Johnson Monday, January 15th, 1968. In the…

CH2. The Wildest Medal of Honor Story You’ve Never Heard — Commando Kelly!

The Wildest Medal of Honor Story You’ve Never Heard — Commando Kelly! On the mountainside above Altavilla, the night burned….

End of content

No more pages to load