“PLEASE BE KIND, THE BRIDE IS UNATTRACTIVE” My Mother-In-Law Said Before Guests At Wedding. My Mother-In-Law ruined my wedding day by humiliating me in front of everyone with cruel words.

Part I

I apologize for an unattractive wife. That was how my mother-in-law chose to welcome me into her family—by wrenching the microphone from my father-in-law’s hands and lobbing those words across the reception hall as if she were throwing a stone at stained glass. The hall froze mid-breath: a violinist’s bow hovering above a string, a waiter caught with two flutes of Champagne, my mother’s hands clenched white around a folded napkin she’d sewn lace onto the night before. Ruth—my new mother-in-law—looked satisfied. The room looked stunned. I felt… hollowed.

I turned to Steven, my husband of a few hours, searching for a lifeline. He smirked. A small, crooked thing, as if he had expected a spectacle and received precisely what he ordered.

A chair legs scraped. An older gentleman rose deliberately, an audible protest etched into the wood against marble. “Is that all you wanted to say?” he asked, voice even, gaze unflinching.

He moved toward me with the sure stride of someone who has made a thousand decisive turns in his life and never regretted a single one. Steven’s eyes widened. The man ignored him, took my arm, and said, almost kindly, “Let’s get out of here.”

He led me from the room while the train of the dress I hadn’t wanted in the first place dragged like a wounded thing. We walked the hotel corridor in a silence that hummed with all the words I couldn’t find.

My name is Angela. Thirty-five. Only daughter of a short marriage that ended when I was in elementary school and old enough to memorize the exact timbre of doors closing. Mom raised me alone and then, because life loves symmetry, I raised her when illness settled into her bones like winter that refused to leave. I learned to be two people at once: the morning-shift receptionist who could smile through any request and the evening daughter who filled pill organizers and set reminders and read aloud to make the loneliness quiet for both of us. I made a habit of setting myself aside.

Steven came late in my story, at a desk where he asked for a visitor badge and I offered a pen. He returned the pen with a joke I can’t remember now, only that it landed on me like sunlight I hadn’t asked for. He learned about my mother. He didn’t flinch. “We can be a family of three,” he said after a year, holding out a ring and a promise that felt like both a rescue boat and an invitation to stop swimming so hard. I said yes because hope insists.

When we told our parents, Mom cried into my hair until her tears dampened the roots. Ruth sharpened her voice like a blade. “I don’t recognize a woman from a single-parent family as a worthy wife,” she said at our first visit, the way someone might declare a policy.

From then on, every detail of the wedding became another stage for her contempt. She found my age unacceptable, my face plain, my patience weak, my mother—a woman she’d never met—foul enough to accuse of infidelity. Steven said very little whenever she spoke, except to remind me not to upset his mother, as if Ruth were a priceless vase and I were a cat with a history of knocking things down. In private, he wanted harmony. In public, he wanted compliance.

When we went to choose a dress, Ruth arrived uninvited, trailed by opinions like a veil. “I’ll choose the best one for you,” she announced, already flipping through silk as if she owned my body and the life it would wear. Steven smiled. “Mom has great taste,” he said. “You’re happy about that, aren’t you?” I told them, gently and then firmly, that I would choose my own dress. A small boundary, but mine. Ruth pouted. Steven scolded. I held my ground. I didn’t know I’d pay for that “no” with a future I hadn’t even stepped into yet.

On the morning of our wedding, in the hotel dressing room, Ruth looked me up and down and sneered, “What an awful dress. The veil’s tasteless. You’d look better in a garbage bag with a sale flyer on your head.” I smoothed the veil with my palms. Mom had sewn it by hand, embroidery like tiny constellations. “We chose it together,” I said. “I love it.”

“You’re going to wear something chosen by a woman who cheated and got dumped?” she barked, and then she did it—pulled a travel cup from her purse and tossed the coffee over my gown. Brown bled through white in a spreading bruise.

“Stop! What are you doing?” I pressed a towel to the stain, but the dress had already learned its ruin. Ruth stood there, triumphant. “This is what happens when you don’t listen to me,” she said. “I left a dress with the staff. You’ll wear that.”

My hands shook. I found Steven in the waiting room and told him what happened. He didn’t flinch. “What do you want me to do?” he said. “The CEO is suddenly attending. If I show well today, I might get promoted. There’s no time to worry about your dress. Just do as Mom says.” When I protested, his face twisted into Ruth’s for an instant. “Enough. You’re annoying,” he snapped, and then, catching himself, he apologized in a voice that sounded more terrified of opportunity slipping away than of my heart breaking.

The ceremony itself was a script followed: vows shaped by tradition, rings slid onto fingers gone cold. I told myself to endure; it was one evening. I could reclaim the rest. Then the speeches began, and Ruth—already flush with the victory of my ruined dress—stood up and burned the rest of my patience to ash. She announced my supposed ugliness, my upbringing, my lack of worth. She promised to “discipline me into a better wife.” My father-in-law tugged at her sleeve, begged. She shrugged him off.

A man rose. He came to me. He said, “Let’s go.” And Steven, suddenly ashen, whispered, “Why is the CEO here?”

Because the man who took my arm was his CEO.

Because the man who took my arm was also my father.

We were in the dressing room when the truth settled. “You told me you couldn’t come,” I said. “Important meeting.”

“It ended early,” Dad replied. “I came to deliver a gift, ran into an employee, asked the names of the couple, and learned the bride was my daughter.” He smiled at me with a sad kind of pride. “Your mother thought it would be a good surprise.”

The door opened. Ruth stepped in, voice suddenly dipped in honey. “Angela, you can’t run off like that,” she cooed. Her coo broke against my father’s stare.

“Who caused this?” he asked, calm the way rivers look calm before a waterfall.

“It was just a little joke,” Ruth said.

“How dare you make a vulgar joke at my daughter’s expense,” Dad replied.

She faltered. “Well—if it wasn’t a joke—”

“Then you seriously called my daughter ugly?” he finished. She blinked at the trap she’d walked into. Steven burst in and bowed his head. “I apologize for my mother’s rudeness,” he said to my father.

“You’re apologizing to the wrong person,” Dad said. He nodded toward me. “Start there.”

Steven turned to me and grabbed for contrition. “I’m sorry, Angela. Mom did it on her own.”

“If that’s the case, why didn’t you stop her?” I asked.

“I was shocked,” he stammered. “Besides, Dad tried—”

“You were grinning,” I said. “Comfortable.”

“That’s your imagination,” he snapped, then spun to Ruth. “You’re the only one to blame.”

“Steven,” Ruth hissed, “didn’t we agree to discipline this cheeky wife together?”

“Don’t say unnecessary things,” he hissed back, palming her mouth in a ridiculous mime of chivalry. My father watched them like a man studying a bad play and waiting for the lights to come up so he could demand his evening back.

“Explain,” Dad said.

Steven’s spine softened. Once a lie begins to sweat, it becomes slippery. “When Angela insisted on choosing her dress,” he began, “Mom said she would become cheeky if not disciplined.”

“What’s wrong with choosing my own dress?” I asked.

“It’s natural that a wife listens to her mother-in-law,” he said, and looked surprised at how easily the sentence left his mouth. “If she can’t, she’ll become a wife who won’t listen to her husband. There’s no point marrying a woman on the verge of becoming an old hag if I can’t make her listen.”

There it was. The truth pulls other truths with it. “Did you ever love me?” I asked.

“You have savings,” he blurted. “I thought we could build a two-family house, make you work, Mom and I could be comfortable, and—” He heard himself then, too late. “That’s not what I meant—”

“It’s exactly what you meant,” I said. My hands were very steady. “We’re done.”

“We can’t send guests home,” he protested. “We’re married. You can’t divorce so easily. If we overcome this wall—”

I took my phone from my bag, scrolled to the folder labeled with a word I’d never wanted to use again: Evidence. I pressed play. Ruth’s voice filled the room, spitting poor and ugly, shouting accusations about my mother’s imagined sins, killing the air with every syllable. “I recorded everything,” I said. “For a judge, if needed.”

Ruth’s face drained. “I was just trying to discipline my daughter-in-law.”

“Please say the same thing in court,” I replied.

“And at work,” my father added. “I’ll reconsider your son’s position too.”

Steven crumpled to his knees. “Please forgive me,” he said. Ruth followed, the two of them kneeling like supplicants to a god they didn’t believe in. They reached for the hem of a dress already ruined by their hands.

“Silence,” I said, surprising myself with how the word felt in my mouth—solid, like something that could hold weight. “Go to hell.”

I left the room.

Part II

The next days moved like a police report: clean, chronological, unembellished. I filed a claim for emotional distress against Ruth and a petition to nullify the marriage before it could gather even a day of legitimacy. My father covered legal fees I couldn’t have afforded without gutting my future; I argued with him about that and lost. “Let me be your father,” he said. “I didn’t get to be enough of one.”

Steven’s colleagues learned what happened—news travels in offices like fire along curtains. The ones who had attended the wedding carried the story; the ones who hadn’t tasted the scandal as if it were salt. Steven walked into rooms and the rooms cooled. At my father’s urging, the company reassigned him to a remote branch in Nebraska. “A soft landing,” Dad said, and I heard all the ways mercy can still be justice.

Ruth’s sister called my mother to apologize for “the scene.” “She always believed her ugliness was a reflection,” the sister said, then gasped at her own phrase and begged forgiveness from the world and the phone line. Ruth’s relatives, embarrassed to be related to a headline, stopped inviting her to things that had chairs and centerpieces. Her husband filed for divorce. She left the house with a suitcase and a crack in her voice, the kind that comes from a throat used to shouting finding itself empty.

I kept working. I learned that grief feels very much like nausea—you’re not dying, but your body is convinced something poisonous is inside you. I sat with Mom at our small kitchen table. She sewed while I sifted through documents: annulment paperwork, receipts the hotel had already printed with our names as if we were a legend who couldn’t be unprinted. “Did I raise you too strong?” Mom asked quietly, eyes on the needle. “Or not strong enough?”

“You raised me to live,” I said. “That’s all any parent can claim.”

When the hotel finally sent the balance due, I forwarded it to Steven with a note: Since your mother caused the cancellation, you and she will cover the full cost. He responded with three messages in a row: You’re cruel. You’re making a fuss over one outburst. You’ll never find anyone else. I sent him a copy of the audio files’ transcript. He stopped writing.

My father and I met for coffee in a cafe he’d never taken me to, one near his office where the barista knew his order and looked at me like she was trying to spot the resemblance. “Why didn’t you tell me you were the CEO?” I asked.

“You never asked,” he said, then softened. “And if I had told you, I worried you’d start asking me to solve things I should let you solve. I didn’t want to be a shortcut in your life.”

“You were one this week,” I said, and smiled to show I wasn’t ungrateful.

“I’ll try not to be again,” he said, and we laughed because love sometimes needs a joke to break its tension.

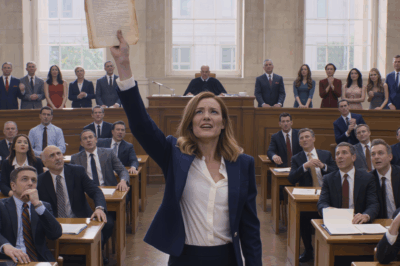

The court date came. The judge listened to the recordings without blinking. Ruth stared at the table. Steven dabbed at his eyes with a tissue he didn’t need. My lawyer spoke sparingly; the evidence was a chorus that required no conductor. The judge granted the annulment. The gavel’s soft tap sounded like a lock turning in reverse.

When we exited the courthouse, November had sharpened itself against the wind. My father tucked Mom’s scarf tighter around her throat and gloved my ungloved hands. We stood on the steps like a family that had learned how to make a small circle and defend it. “Dinner?” Dad asked. “Yes,” Mom said. “But not the old restaurant. A new one. I want a new memory to eat.”

We ate. We laughed in the haggard way people laugh when something heavy finally sets down and doesn’t roll back onto them. I went home, took off the veil that still smelled faintly of coffee, and laid it across my bed. “I’m sorry,” I told my mother’s stitches. “You were perfect.”

The doorbell rang. I opened it to find my father-in-law—no longer my father-in-law—standing on the stoop with a cardboard box. “This is yours,” he said, pushing it into my arms. “Ruth’s ‘backup dress.’ She ordered it three months ago. She planned the coffee. I should have stopped her. I’m sorry.”

Inside the box lay a dress I never would have chosen: mermaid cut that mocked my hips, a bodice too tight for breath, sequins like small, loud lies. I laughed until tears came, then cried until laughter returned. I left the box in the hall. I refused to let it enter any room that knew me.

The next morning, I woke early and cleaned the kitchen like a rite. I washed the last glass that had tasted celebration and set it to dry upside down. I made coffee and didn’t flinch. When it finished, I poured it, then walked to the trash and tipped the cup, letting the liquid fall into the bin. A tiny exorcism.

Mom shuffled in, wrapped in the sweater she wore when she didn’t want to wear a body. “What now?” she asked, not to the room but to time.

“Now,” I said, “we work. We rest. We eat something good. We live like this never happened and like it changed everything. We do both.”

Part III

Work didn’t care about my personal plot. It wanted budgets and reports and an opinion on whether the new lobby arrangement made the building feel more welcoming. It didn’t, but I said it did because some lies are harmless and the plants looked happier.

In the quiet hours, I started writing down all the versions of myself I had tried to be to get love: the accommodating one, the humble one, the almost invisible one. I wrote down what I wanted to be now: the one who doesn’t audition. I read the list to Mom while she folded towels. She nodded after each item like a metronome of approval.

Dad asked me to have lunch with him “as colleagues,” he said on the phone, with a grin I could hear. At the restaurant, he introduced me to someone from HR, who asked—off the record—if I wanted to submit a formal complaint about Steven’s conduct at the reception. “My feeling about that evening is already on file with the universe,” I said. “I don’t need to carve it into office walls.”

“Noted,” she said. “If that feeling changes, my inbox is armored.”

“You speak like a person who has been a woman at work,” I said.

“I am,” she replied. “And I am tired of teaching offices to act like people.”

After lunch, Dad and I walked two extra blocks because it was the kind of winter day that tricks you into thinking cold is clarifying. “Do you hate me for not stopping the marriage earlier?” he asked.

“I didn’t tell you what needed stopping until it was too late for you to stop it,” I answered. “I’m not assigning you a power you never had.”

He exhaled. “I love you.”

“I know,” I said. “I can feel it.”

We planned a small dinner at Mom’s—just the three of us, a corrected version of the past. Dad cooked, badly. Mom supervised, carefully. I set the table with the china we saved for a life we never quite lived. We used it anyway. We let ordinary food sit on fancy plates. It looked like forgiveness.

Steven emailed once from Nebraska: a long apology written in the grammar of panic. I didn’t respond. Some doors you close gently right before replacing them with walls. I archived the email into a folder named Lessons and left it there like a label on a jar of something you’re done tasting.

Ruth tried to call. I blocked the number. She sent a letter, a strange thing with no postage—handed off to a cousin who passed it through Mom’s sister who pressed it into my palm at a grocery store aisle under a speaker playing holiday music. I opened it at home and found a single line: Please be kind, the bride is unattractive. It was the sentence from the reception, rewritten as a plea, repointed at herself. I stared at the words until they doubled. I didn’t know if the letter was an apology or a self-pity monument. Either way, I folded it once and tucked it under the ruined veil and closed the box. My kindness would not be poured where it wouldn’t water anything.

Winter rounded itself into the new year. I decided to take myself on dates: a matinee on a Tuesday, a bakery run before dawn, a museum where I stood too long in front of a painting of a woman who looked like she’d just discovered a secret and wasn’t sure if she should tell it to the room or save it for herself. I bought a small plant and didn’t name it. If it lived, it lived. If it didn’t, I would not make it a referendum on my capacity to keep things alive.

I kept the ring in a drawer for a month, then woke one morning with a clarity so clean it tasted like the inside of an apple. I took the ring to a jeweler and asked them to melt it down. “What would you like instead?” the jeweler asked.

“A charm,” I said. “Something unromantic. Something true.”

He crafted a small gold key, plain, honest, the size of a decision. I hung it on a chain and wore it under sweaters where only I could feel it rest against my sternum like a reminder: the door is mine.

I visited HR at my own office to ask about starting an internal support circle for employees dealing with family turmoil. “Not therapy,” I said. “Just a table and chairs and a monthly agenda that says, ‘You’re not alone.’” They said yes with relief. The first meeting, six of us sat and tried to find the lane between oversharing and connection. By the third meeting, we didn’t need lanes; we had a map.

One woman, Linh, whispered, “My sister has lived with me for five years. I keep buying time with my sanity.” She looked up, eyes bright with fear and freedom. “I think I’m going to ask her to move out.”

“How can we help?” I said.

“Hold me to it,” she replied. “And then help me pick a lock for my bedroom door that isn’t metaphorical.”

We laughed. We wrote scripts. We practiced saying, “I love you, and the answer is still no.” I walked home feeling like the world had grown a new room where women could put down what they’d been handing to others for years.

Part IV

Spring came with daffodils elbowing through stubborn soil. Mom’s health steadied into a rhythm we could both dance to without looking at our feet. Dad invited us to a small concert—an employee’s daughter playing cello in a community orchestra. We sat in the third row and let the music pull thread through the holes the winter had left.

After, in the lobby, a woman approached me with the bright awkwardness of someone about to say something brave. “You don’t know me,” she said, “but I was at your wedding. I was a guest of a friend of Steven’s. When your mother-in-law spoke, I—” She swallowed. “I’ve never seen anything so cruel.”

“Me either,” I said. “Until I looked at the mirror later and saw the face of someone who survived it.”

She nodded. “I’m leaving a man who talks to me like that when no one’s listening,” she said. “Your leaving helped me imagine mine.”

I didn’t cry until after she walked away. When I did, it was with gratitude, a feeling that turns grief into compost.

The lawsuit settled. The hotel fees were paid by Steven and Ruth without further dramatics, an anticlimax I treasured. The bank transferred the last reimbursement. I closed the account I’d opened for wedding expenses and opened a new one called Joy. I put a little in every Friday, even when the week had not been joyful. Especially then. The fund was for unplanned blossoms: a train ticket to see a friend, a book I loved in hardback, an afternoon class in hand-building clay bowls that would all come out crooked and perfect.

One evening, I cooked dinner and plated it on the wedding china again. Mom raised an eyebrow. “So we’re not saving it?” she asked.

“For what?” I said. “A marriage?” We laughed. We ate. I washed the plates with careful hands and no reverence. Life is too short to love objects more than it loves us back.

A year after the wedding-that-wasn’t, my phone buzzed with a number from Nebraska. I didn’t answer. It buzzed again and again until the buzzing became a soundtrack. I turned off the phone and went for a walk, keys in my pocket jangling a rhythm that felt like a small anthem. When I turned it back on at the park, there was a voicemail. Steven’s voice was thinner. He wished me well in words that made me believe he had learned how to say them to hear how they sounded in his own mouth. I deleted the message and wished him well in my head and then placed him back into the past where he belonged, like a book I’d finished and didn’t need to re-read even to find a favorite line.

Mom asked me once if I would ever want to remarry. “I’m not disinterested,” I said. “I’m uninterested in being erased.”

“And if someone sees you clearly?” she asked.

“Then they can knock,” I said, touching the charm at my neck. “And I will decide whether to open.”

We started having dinners with Dad regularly. Not the performative kind. The soup-and-stories kind. He told me about mistakes he’d made that had nothing to do with us, other lives where he’d chosen wrong and learned slowly. We laughed at the way time humbles even those who think they’re its managers. We let ourselves be a family that had been broken and built and wasn’t ashamed of either stage.

On a Saturday in early summer, I took the ruined veil from its box and carried it to a seamstress named Pilar who had once remade a friend’s grief into a christening gown. “Can you do something with this?” I asked.

She spread the fabric across her table like a map. “What do you want it to become?” she said.

“Curtains,” I answered, surprising myself. “For the room where I read.”

She smiled. “Then we will measure for light.”

A week later, the veil hung in my window, reinvented, filtering morning into a gentler version of itself. When sunlight passed through Mom’s stitches, it made constellations on the floor, and I walked through them barefoot, a woman who had finally learned that even after someone tries to humiliate you in front of the world, you can invite the world back in through a window you chose, softened by lace that survived.

I am focusing on my work. I am not courting marriage; I am courting peace. Sometimes the two meet for coffee, and sometimes they sit at separate tables and wink. That is enough.

If you need a scene to end this story, picture this: a kitchen at dusk. A pot cooling. Two plates drying. A woman standing before a window veiled in lace, wearing a small gold key on a chain. Behind her, a mother humming while she folds a towel. Beside her, on the counter, a box with a dress that never learned my name and never will. On the table, a bank envelope with a note tucked inside: Balance—Paid in Full.

I accept the balance’s quiet. I accept the full. I accept that my life is not the sum of the wrong rooms I have stood in, but the rooms I have learned to leave and the ones I have chosen to build.

That night, I switched off the kitchen light and the window glowed. The lace held the last of the sun. I slept well. In the morning, I brewed coffee and did not think of stains. I thought of work. I thought of the Joy fund. I thought of the woman at the concert and Linh’s lock and Pilar’s hands and my father’s arm offering mine to steady me, not because he thought I would fall, but because he knew I didn’t have to walk out alone.

Some stories end with punishment. Mine ends with clarity. With a window. With a door and a key I keep close. With a promise I made to myself and kept: I will not be the kind of bride they can insult into silence. I will be the kind of woman who learns the language of leaving—and the even braver language of staying with herself.

And if anyone asks what happened to the girl whose wedding was ruined, tell them she built a life instead. Tell them she hosts dinners on fancy plates and hangs curtains made from what tried to break her. Tell them her mother laughs again and her father makes terrible soup and both are miracles. Tell them that when an old sentence—please be kind, the bride is unattractive—tries to climb the stairs of her memory, it finds the door locked from the inside.

It finds a key on a chain.

It finds me.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

My Dad and “Deadbeat” Brother Sold My Home While I Was in Okinawa — But That House Really Was…

While I was serving in Okinawa with the Marine Corps, I thought my home back in the States was the…

I Left With $12—Two Years Later, I Bought Their House In Cash

I Left With $12—Two Years Later, I Bought Their House In Cash Part 1 The scent of lilies and…

HOA Put 96 Homes on My Land — I Let Them Finish Construction, Then Pulled the Deed Out in Court

HOA Put 96 Homes on My Land — I Let Them Finish Construction, Then Pulled the Deed Out in Court…

Mom Sold My Childhood Home For $7 And Lied About It

Mom Sold My Childhood Home For $7 And Lied About It Part 1 The email hit my inbox like…

My Mom Sent 76 Invites—Guess Who She “Forgot”?

My Mom Sent 76 Invites—Guess Who She “Forgot”? Part 1 The email wasn’t even addressed to me. It arrived…

Left Out of the $75K Inheritance “Because I Didn’t Marry Well”—Until My Name Was Read Last

Left Out of the $75K Inheritance “Because I Didn’t Marry Well”—Until My Name Was Read Last Part 1 The…

End of content

No more pages to load