Parents Told Me, “Skip Thanksgiving — We Need Space.” But Their Regret Came Quickly

Part I — The Message

The text arrived while I was rolling out pastry on my kitchen island, the air fragrant with butter and nutmeg.

Mom: Hi honey, your dad and I are thinking of keeping Thanksgiving simple this year. Just us, Tessa and the twins. Hope you understand.

I read it twice, then set my phone between the flour jar and the cooling rack. The edges of the message felt polished—careful words like polished stones, heavy in the palm.

“Simple,” I said out loud to the empty room, and the word fogged the window above the sink. Simple as in smaller. Simple as in without you.

I’m Avery Lane, thirty-five, an interior architect who learned how to draw grace into rooms that never had any. For years, I’ve fitted myself into corners at my family’s holidays—the extra chair, the “we’ll add a leaf,” the seat nearest the kitchen so I could jump up when Mom needed anything. Always a place if needed, and never when wanted.

I wiped my hands, thumbed a reply that was more controlled than my chest felt.

Me: No worries, Mom. Enjoy.

A dot pulsed. Disappeared. Returned.

Mom: We’ll do something with you and your friends later. Maybe a December brunch?

Later. Later has been my family’s favorite calendar square for as long as I can remember.

I placed the phone face down. On the other end of the counter, a set of engraved brownstone keys glinted beside a folder stamped COLD RIVER FARM—CLOSING. Six weeks earlier, I’d signed for a 1790 farmhouse on the Vermont border, white clapboard with cedar beams and a wide, stubborn porch that looked out on birch trees and a slope of mountains already collecting shadow. It wasn’t a retreat; it was a declaration. Eight bedrooms. A long table. A forgiving hearth. Enough room to seat the life I’d built beyond the house that never learned to fit me.

The batter’s perfume rose and softened the sting in my throat. I texted Aunt Miriam, who taught me how to scorch paprika and keep my own counsel, and my cousin Eli, who sends postcards from every city his band passes through. I messaged my best friends, people who text I’m on my way instead of Are you sure? and a couple of my favorite clients—single parents, neighbors, the yoga teacher who pressed her card into my palm after class and said, “You look like someone who needs people.”

Me: Thanksgiving at the farmhouse. Come if you can. Rooms are made. Fire’s lit.

They didn’t ask if my parents were coming. That’s what real family knows to avoid pressing.

Part II — A House That Fits

The farmhouse did what good rooms do—it lent its bones to our joy. Eli arrived first with a case of sparkling cider and a guitar he treats like a saint. Aunt Miriam followed with a chest of vintage linens she “borrowed permanently” from her mother and two cornbreads still too hot for plastic wrap. Then came Priya and Nora with twin toddlers and granola bars they called “currency.” My assistant Max knocked with his boyfriend and a crate of pumpkins that made the porch glow like a runway.

By Wednesday night, the house hummed at the exact frequency of belonging—footsteps overhead, laughter lifting in round notes, a dog’s collar clicking down the hall. I’d drafted every corner the way a conductor lays out a symphony: bunk rooms made up with wool socks and hand-lettered notes; a library corner with a tin of dates and a stack of board games; candles tucked into mason jars along the stairs. The kitchen island was a democratically messy kingdom of pie crusts, brussels sprouts, and stories we hadn’t told in too long.

In the middle of tossing salad, my phone buzzed again.

Mom: Are you alone tomorrow? If so, Dad and I can swing by after the game. Quick dessert.

I stared at the screen until the text blurred. The two of them and Tessa and the twins, their version of “simple,” barely five miles from my apartment in the city, while I steered a holiday the same way I’ve always steered my life—quietly, deliberately, and without them.

Me: Hosting at the farmhouse. Full table. Have a good one.

Aunt Miriam slid beside me with a jar of cumin and her unerring read on the room. “Did Catherine do it again?” she asked—Catherine being my mother, to everyone who has ever needed to use her name like armor.

“She did,” I said, stirring with more force than necessary.

Miriam took the spoon, gentled it. “Then you know what to do. Feed who showed up.”

That night, under a sky thrown full of stars, we sang badly, and the house allowed it. When I went to bed, someone had left a mug of lemon tea and a note on my nightstand: We’re here because you are.

At 7 a.m., my phone buzzed with a new text I didn’t expect.

Tessa: Mom wants to make sure you aren’t lonely. We can FaceTime you between the halftime show and dessert.

I thumbed a smile I did not feel.

Me: I’m cooking for sixteen. Might be busy. Enjoy.

Part III — The Photo

Thanksgiving morning came draped in white—the fields out back glittered with a light frosting, the kind that makes footprints look like signatures. Our private chef (stubbornly local; I insisted she sit and eat with us afterward) basted a turkey that smelled like every place I’ve ever forgiven. Kids galloped through the mudroom pulling on boots; grown-ups stole spoonfuls of roasting carrots and kissed each other near the coffee pot like they’d trained for it.

At noon the photographer arrived. I had hired Trevor because the last house he shot for me looked like memory instead of marketing. He drifted around us as if he were learning choreography: lit faces bent over dough, Priya’s toddler asleep inside her sweater, Eli showing Max’s boyfriend how to knot a napkin like a sailor. Trevor held out the screen once, and I saw the farmhouse holding us as if we’d always belonged to it.

At that exact moment, another text lit my phone.

Mom: Turkey in at nine. Parade, then naps. Quiet, just like we wanted. Are you sure you’re okay? You can still come by after.

I stepped onto the porch. The air tasted like frost and possibility. Out in the meadow, Eli and the toddlers were building what might be a snow dragon or a toppled castle—its exact identity didn’t matter. I considered my choices. Inside, laughter. Outside, pine lined hills. On my screen, the person who taught me how to cut out paper snowflakes and how to cut myself down for easier packing.

I typed with a steadiness I hadn’t felt since I left her house at twenty-two with a duffel bag and the kind of resolve you can only afford once.

Me: I’m better than okay. Hosting. We’re about to sit down.

A dot. Then, Where?

For a woman who always knows the layout of any room she enters, she has never bothered to learn mine.

Me: Vermont farmhouse. Bought it in September.

Silence. I slid the phone into my apron and went back to making mashed potatoes with Aunt Miriam’s technique—heat the cream first, then fold like you’re asking the potatoes to forgive you for what you’re about to do.

We ate under strings of lights that made the rafters look like constellations had moved inside for better company. To the right of my plate, Max spilled cranberry sauce and apologized to the linen like it had feelings; to the left, Nora told a story about a Thanksgiving in Tucson where the stove died and twenty people ate raw Brussels sprouts and pretended to like them. We passed bowls and apologies and then more bowls.

Trevor took a shot from the mezzanine: twenty people, cheeks flushed, heads tipped back laughing, light catching the glass and the joy. Later, he sent it to me and I wept at the sight of my own shoulders relaxed.

After dessert—three pies, one accidental tart, and a bowl of whipped cream that was more architecture than food—we stood on the front steps and yelled into the cold night for no reason at all. The kind of communal howl you forget you need. Someone posted Trevor’s photo. Then Aunt Miriam posted six more with a caption that was a hug disguised as a sentence: We go where we are loved. We’re thankful for Avery, who builds rooms and families with the same hands.

My phone began to buzz like a hive. Messages from cousins who had chosen ease over effort in previous years. Colleagues. Former clients. And—because the internet is a small room with a lot of windows—a message from my mother that wasn’t meant for me. A screenshot, sent by a neighbor who has always found a way to show up:

Mom in the Family Group: Does anyone know what this “farmhouse” is? Why wasn’t this shared? People are asking why we weren’t there.

Space, I thought. You asked for space.

Part IV — The Knock

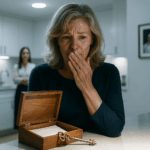

The knock came at three-fifteen, right as Priya and I were packing leftovers into Tupperware towers and labeling them like we were shipping aid. Eli opened the door, expecting a neighbor or Trevor with a forgotten lens cap. He stepped back, surprised. “Avery,” he called, his voice more neutral than he meant it to be. “You’ve got… visitors.”

My parents and my sister stood on the porch, bundled in quilted jackets that belonged to catalogues and decisions. They looked smaller in the cold. Behind them, the twins somersaulted inside their puffer suits.

For a flash of a second, sixteen versions of twenty holiday tables collapsed into one—barbs disguised as jokes, last-minute place settings as afterthoughts, the soft threadbare cardigan of me trying. Then the image passed, and there was only this: three people who had not wanted me and now wanted something.

“Avery,” my mother began, pulling the familiar tone around her like mink. “We were in the area, and—”

“You were in the city,” I said. “This is two hours north.”

My father shifted his weight like a man who used to own rooms and had come to ask for a loan. “We saw the photo,” he said simply.

“I know,” I replied, because a woman at the general store had texted Aunt Miriam from the checkout line and nothing in small towns ever stays inside one mouth.

“We… underestimated,” my mother said, the word catching like a fish bone. “Forgive the wording. We thought you’d be alone.”

I stood in the doorway, leaned my shoulder against the frame that I had chosen, paid for, stained, sanded. “And you decided space.”

“Your sister’s boys—” she started.

“Are the weather,” I finished, not unkind but not soft. “You always bend for the weather. You never bend for me.”

Behind me, the house murmured. The toddlers squealed at a cupcake they’d found. Someone tuned the guitar again. The smell of cinnamon and pine and the part of a fire that settles and glows filled the air between all of us.

“We’d like to come in,” my sister said, eyes slipping past me the way they always have, toward warmth that didn’t belong to her.

“For pie?” I asked. “For photos?”

Her mouth tightened. She reached for the twins’ sleeves, maybe to manufacture urgency. “We’re family, Avery.”

“We are,” I said. “That’s why I won’t pretend nothing happened. You asked me to skip Thanksgiving. I did. I built one.”

My father opened his mouth, then closed it. To his credit, he didn’t reach for the old phrases that used to unspool me—stop making a scene, you’re too sensitive. He looked at the porch lights—and I swear he noticed they were warm LEDs because I am his daughter—and then he did something I hadn’t planned for.

“I was wrong,” he said. The words sat awkward in the air, unaccustomed to the climate. “We were wrong. We’re… sorry.”

My mother’s head snapped toward him like he’d betrayed a treaty. He took her gloved hand and held it, an anchor and a dare. “Catherine,” he said softly.

She looked at me then in a way she hasn’t since I came home from my first dorm and told her I wanted to design buildings instead of collect them. “I thought,” she started, and then the truth made itself available: “I thought if I made it small enough, I wouldn’t have to be afraid of it changing.” She gestured toward the house, toward the people, toward the laughing that made the porch boards vibrate. “You changed it without us.”

I didn’t rescue her. She has learned to swim in other people’s needs her whole life. The twins tugged at her coat and pointed at the dog. “Puppy?”

“Can we sit on the steps?” my father asked. “Just for a minute. We’ll go after.”

Behind me, Aunt Miriam breezed into the hallway, took in the tableau with the kind of look that makes wallpaper feel seen. “You can sit on the steps,” she said kindly, then turned to me. “But we’re not dragging out more chairs. The table’s full. The kitchen’s a mess. They can have a slice to go.” She held out two paper plates like verdicts.

My mother took them. My sister wavered. The twins ran toward the snowbank, and Eli knelt to show them how to shape it into something that would be gone by Sunday. It was not a reconciliation. It was a threshold.

They sat. They ate outside. They listened. Through the open door, they could hear the toasts—Max at the mantel thanking everyone for teaching him that chosen family is not a consolation prize; Priya making a motion to declare all future Lanes-gatherings gluten-optional but love-mandatory; Aunt Miriam raising her glass to “the girl who finally built a house that fits.”

My mother’s pie fork trembled against the tin. She looked over the rim of her plate and met my eyes. This time I didn’t feel like a child peeking into a room where she didn’t belong. I felt like a woman standing in a door she had hung. “Space,” I said softly. “Sometimes it shows you what you’re missing.”

She nodded once and didn’t pretend it was dandruff in her eye.

They left after ten minutes. It was the best ten minutes we’ve had in years. When they reached the bottom of the path, my father turned back and lifted his hand in a small wave that asked no answer from me. I gave him one anyway because bridges are useful as long as you refuse to be the only one who repairs them.

Inside, Eli struck a chord that felt like a grin. “All right,” he declared. “Let’s butcher a carol.”

We did. The house held it without wincing.

Part V — The Morning After

The posts had been percolating all night. By morning, the internet had done the thing it does when joy is too well lit to hide. My inbox bulged with messages—the old neighbor who had taught me how to ride a bike, the teacher who had told me I made rooms feel less lonely, a woman I didn’t know who wrote simply: Seeing your table makes me brave.

Then came one from my father. No subject line. No argument. Just:

Avery,

We asked for space and saw what we created.

Your mother and I would like to come by tomorrow with a basket—just bread and butter, nothing to be photographed. We’d like to help with dishes. We’d like to listen.

If the answer is no, we will accept it.

Love, Dad.

I read it twice. I set the phone down on the counter where dough rose under a damp towel. I leaned my hands on the cool quartz and let the question fill the room: do you let people back into your house before they have learned how to not rearrange the furniture in your soul?

“A letter?” Aunt Miriam asked, appearing like the universe does when you’re deciding whether to poke it.

“Something like it,” I said. “They want to come back. Non-photogenic.”

Miriam considered, then nodded toward the sink piled high with what love leaves behind. “Let them do the dishes,” she said. “But no seats until they ask who to thank.”

At noon, I bundled everyone into cars for one last walk down the ridge to the covered bridge. We made coffee to-go, pulled hats low, and wove into the white woods like a bright thread. Eli sang badly; the toddlers fell and laughed; Max kissed his boyfriend quiet and right on the trail. It was life. It was mine.

At the bridge, Priya turned to me. “You good?” she asked.

“I’m good,” I said, and when she kept looking, I added the thing I didn’t say for too many years. “And even when I’m not, I’m not alone.”

We walked home under a sky that kept the cold for us, just until we got inside. The farmhouse, stalwart and smug, looked at me like: See? I told you. I told it back in a whisper only wood understands: “I know.”

When the last car pulled away and silence filled the rooms like a blessing, I sorted plates and clicked lights off and stood in the big, forgiving kitchen to breathe. The phone buzzed once more. A text from Tessa.

You made something beautiful.

Can I… help with Christmas? Not from the center. From the sink.

I stared at the screen until the words steadied. Then I typed a sentence that would have made the girl bending herself small at twenty-two weep with relief.

You can help when you’re ready to follow, not lead.

Christmas is full.

But I’ll leave room on the porch.

Part VI — How We Keep It

A week later, a handwritten card arrived from my mother. It was not an apology in the language she knows; it was as close as she could reach. We thought smallness would save us from change, she wrote. You changed anyway. We’d like to learn from you. Next time, what should we bring?

I bought stamps. I wrote back. Bread and butter. And your hands for dishes. And your ears for stories you were not the first to tell. I did not sign Love. I signed —Avery. Steady. Not cold; simply true.

In the months that followed, the farmhouse became what I’d promised myself: a house that fits. The kitchen kept forgiving us when we scorched sauces. The porch kept seating more than we’d planned for. In late January, a blizzard cut the power and twenty of us ate cheese and apples by the firelight and recited terrible poetry while Max and Eli argued about whether a sonnet can be written on a phone.

On a Wednesday in February, my parents arrived unannounced with a bag of oranges and a humility I didn’t recognize. They stood on the porch until I invited them in. They washed six pans while Eli and I argued about paint colors for a townhouse in Brooklyn. My mother listened to Nora talk about a grant proposal like it was the only conversation happening on earth. My father looked at the beams and didn’t say these should be maple or you should have kept the stain lighter. He asked instead, “Did you leave these scars on purpose?” and when I nodded, I saw his mouth want to shape a correction and then decide to make room for wonder.

After the dishes were stacked like the end of a blessing, my mother wiped her hands and said, “We can go.”

“We’re not done,” I said, and placed a towel in her hands. “You forgot the island.”

She smiled with her eyes and followed the towel to the work.

You keep a house like this the same way you keep a family: you make tables, and you check the chairs, and you let everyone know where the broom lives. You ask for help and you don’t apologize when you mean no. You don’t let people drag leather suitcases over your heart. You call in the ones who stood with you when you had nothing but a backbone and paper plates.

By the time spring leaned into the fields, the farmhouse had collected new rituals. Aunt Miriam’s Friday soups. Eli’s off-key Wednesday concerts. Max’s habit of leaving tulips by the sink. We kept holidays how we wanted to—Easter with beignets, Passover with laughter dangerously adjacent to sacrilege, Pride with bunting that made the porch look like joy had found a building permit.

On a June afternoon, my mother stood at the window and watched children streak across the grass like escaped brushstrokes. “It’s so loud,” she said, and then, with awe, “It’s so alive.”

I handed her a glass of lemonade and the next part of the lesson. “It’s both,” I said. “That’s how houses breathe.”

She took a sip. “Next time,” she said cautiously, “can I bring pie?”

“You can bring pies,” I said, “if you save room for someone else’s recipe.”

Her laughter came out surprised. It sounded younger than the year.

Sometimes regret arrives quickly—the minute you press send on a text that will echo in an empty doorway. Sometimes it arrives slowly, like light crawling down a stair at morning. The only thing that is not slow is the moment you decide you will no longer live in rooms that do not accommodate the person you had to become.

On the anniversary of the message that used the word space like a weapon, I sat on the farmhouse steps with my chosen family and my training-advantaged relatives and watched the fireflies make constellations that made more sense than any my mother ever hung on the dining-room wall. Eli leaned into my shoulder. Aunt Miriam tucked a blanket over my knees as if I were eighty already. The twins—my sister’s—ran circles around the hydrangeas and did not crush even one.

My phone buzzed on the rail beside me. A text from my father. We saved Wednesdays for you. Bring soup. Or let us bring bowls.

I typed the simplest answer a boundary can hold without being brittle. Wednesday. Six. You know where the broom is.

We ate late that night. We put the house to bed with kind hands. Before I went upstairs, I stood at the threshold and looked at the room I’d built full of people who had built me. “There’s room,” the house seemed to say, and I believed it.

Not because anyone handed me a place, but because I finally understood I could build one, and fill it, and guard it, and still leave, on the porch, two paper plates for pie.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

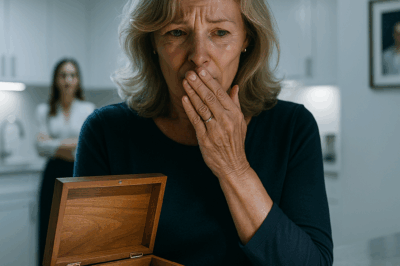

CH2. My Daughter Betrayed Me… But My Late Husband Saved Me

My Daughter Betrayed Me… But My Late Husband Saved Me My daughter thought she could take everything—my beach house, my…

CH2. My Family Skipped My Child’s Surgery, Then Demanded $5,000 — and Called the Bank When I Laughed…

My Family Skipped My Child’s Surgery, Then Demanded $5,000 — and Called the Bank When I Laughed… Part I —…

CH2. The Family Of My Daughter-In-Law Pushed My Grandson Into The Lake… But They Didn’t Know My Brother

The Family Of My Daughter-In-Law Pushed My Grandson Into The Lake… But They Didn’t Know My Brother Part I —…

CH2. After my mother chose my stepfather over me, I was forced to live on the streets at 16. “He’s not worth the trouble,” she said. I cleaned toilets for money. Monday, a detective found me: “Your real father in Germany spent millions searching for you. He left his automobile empire worth $2.1 billion -to claim it, you have 72 hours to your family’s darkest secret”

After my mother chose my stepfather over me, I was forced to live on the streets at 16. “He’s not…

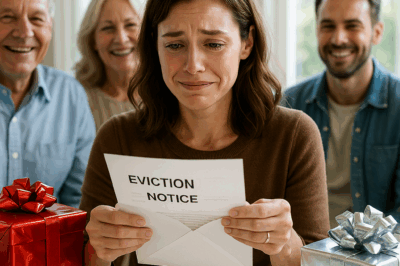

CH2. On My Birthday, My Family Gave Me A ‘Special’ Present. When I Opened It, It Was an Eviction Notice for My Own House. I Smiled as I Returned the Favor on Their Wedding Day…

My Family Gave Me an Eviction Notice on My Birthday. I Smiled as I Returned the Favor on Their Wedding…

CH2. My Dad Sent Me $3,500 Allowance But Mom Sent to My “Golden Sister” for Her Dream—Until I Collapsed…

My Dad Sent Me $3,500 Allowance But Mom Sent It to My “Golden Sister” for Her Dream—Until I Collapsed… …

End of content

No more pages to load