When Major Morgan finally earned her promotion — the moment she had worked for her entire life — not a single member of her family showed up. Not her parents. Not even her husband. They had all flown to Hawaii the day before. But as the TV cameras broadcasted her new rank — “Welcome, Major General Morgan…” — her phone lit up: 16 missed calls and a message from Dad. “We need to talk.”

Part I — The Empty Seats

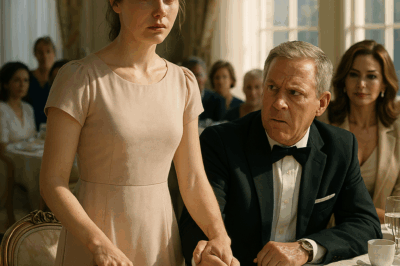

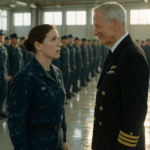

My name is Major General Morgan, and when the second star touched my shoulder, three front-row chairs sat vacant under placards with my family’s names. The band played, the host’s voice carried on, the lights were a hot salt glare, and I did what twenty years in uniform had taught me to do: breathe, salute, stand tall. Somewhere, a lens tightened and captured the image of a composed officer accepting history. No one captured the horizon line gone out behind my eyes.

I had given them everything they would need to make it easy. An itinerary in plain language. A sedan, reserved under their names. Formal invitations done up the way my mother liked them—cream paper, black script, the kind she kept in a drawer under the good silver. I’d even texted them that morning, because I knew how plans slipped in our family the way screws work themselves loose on long drives. Ceremony starts at 0900. Seats reserved.

No reply. When the turn came in the program and my name rolled through the sound system, I still caught myself looking at the center aisle as if my father might surprise me with a last-minute entrance, hat in hand, shame in his eyes, and my mother hurrying after him with a guilty half-smile. Instead, I saw my assistant, Lieutenant Perez, take her place behind the press riser and give me a thumbs-up. I nodded back, kept my shoulders square, and let the pin bite my skin like a benediction I wasn’t sure I believed in anymore.

Afterward, the well-wishers formed a line. “Congratulations, ma’am.” “Honored to serve under you.” “You make us proud.” I shook hands, gave measured smiles, and thought about how many nights I had counted ship wakes instead of candles on a cake. A young sailor pressed a navy blue envelope into my palm. “Someone left this at the front desk, ma’am.” Inside, Daniel’s handwriting looked stranger than it had in months. Don’t wait up tonight. Needed time to think. Congrats.

Outside, the March sun made the world hard and bright. The gulls called over the parking lot. I stood alone in the breeze, letter in one hand and my phone in the other, watching the screen flood: sixteen missed calls from the same Virginia number and a text from my father. We need to talk.

For a minute I could not feel the ground.

Three months earlier, when the promotion recommendation arrived, I had done the old ritual—mailed copies to my parents with a polite note, called my brother, Ethan, leaving a message when he didn’t pick up, and put one crisp letter on the kitchen counter where Daniel dropped his keys. “They’re considering me for two-star,” I told him when he came in. He kissed my hair, said “That’s…big,” and then asked whether I’d remembered to grab milk.

I had told myself then that it didn’t matter who filled a chair as long as I filled the job. It wasn’t until I saw those three blank spaces that I realized how much I had banked on the idea of witnesses.

By the time the edited segment started looping on the local news, I was back in my quarters, jacket folded across the couch, shoes aligned neatly by the door, coffee cooling untouched on the table. Perez texted a picture—me, saluting; the caption: You looked incredible, ma’am. Your father must be proud. I stared at the words a long time, not because they were untrue, but because I could not tell whether they were true or not.

The phone buzzed against the wood again. Same number. Same message. We need to talk. I powered it down and sat in the quiet with the weight of every day I had marched forward on my own. If I answered, it would not be as the officer they had watched on television. It would be as Morgan, the daughter who had spent a childhood learning to fold flags and carry silence without complaint.

Part II — The House We Came From

My father, Colonel Thomas Morgan, ran our house like a post. He believed in wake-up calls, ironed collars, and the kind of lawn you could measure with a ruler. He’d served thirty years in the Army, and when he retired, the habit of command didn’t retire with him; it merely changed branches. My mother, Lorraine, enforced his standards with a gentleness that could cut. If Dad was the order, Mom was the remind.

I came first: bookish, practical, the kid who took apart the toaster to see how the coils heated and never quite learned to put the back panel on straight again. Ethan followed three years later, sun-spilled and easy to love. He laughed with his whole body, lied with his whole face, and could talk our way out of traffic tickets by saying “Sir,” just the right way. Dad took Ethan to Army surplus the week he could walk; he showed me how to make a bed with square corners.

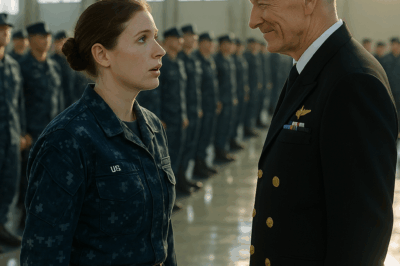

When I told him I wanted the Navy, he looked at me like I had confused the branches out of spite. “The Navy?” he said. “You think you’ll handle that life? The Navy will eat you alive.” When the Academy acceptance letter came, I taped it to the refrigerator so I wouldn’t be tempted to back out. He tore it down without looking at the crest. “You’ll be back by Christmas,” he said. “When you figure out you’re not built for it.”

I wasn’t built for it. I built myself for it.

I learned the cadence of ships and the tang of jet fuel. I learned how to love the math of distance—miles to horizon, knots to port, the way a compass trusts north regardless of who is holding it. I learned to keep my voice level when a room tried to push me to the edges. I learned to ignore the way my chest still tightened every time a banquet included a father pinning a ribbon on a daughter as if it were the most natural motion in the world.

Daniel came later, when I had already made peace with the idea that a life could be vessel and not harbor. He was an engineer who wrote code like he’d been born speaking it, steady and fair. I mistook predictability for devotion. He mistook my devotion for something that would never argue with duty. We made a good picture. We did not make a good home.

When the nomination letter arrived, my father didn’t call. When my mother did, she left a message that said, simply, We’ll see, honey. Flights are so expensive. I pressed my hands flat on the table and remembered the years I had been told the uniform comes first. It turned out that was true when the uniform was his. When it was mine, it became an inconvenience in the story they preferred to tell about themselves.

On the plane to the ceremony, a man in a tie asked me what I did. “Navy,” I said. “Promotion?”

“Yes,” I said. “Major General.”

He whistled, low and sincere. “Your family must be over the moon.”

“They’re…busy,” I said. He nodded in the way strangers do when they realize they’ve been handed a door they cannot open.

Part III — The Call and the Confession

After the ceremony, I stood in the sunlight long enough for the adrenaline to bleed out of my limbs. Then I turned my phone back on.

Sixteen missed calls do not feel like love. They feel like emergency alarms. I tapped the message: We need to talk. It’s about your brother.

My breath thinned. Ethan. The golden son. The boy Dad had bragged about for years even when he hadn’t finished much of anything he started, whose laughter had edged into a laugh he only used when he needed something, whose photos I had stopped liking because every heart felt like permission.

I called. Dad picked up on the first ring. “Morgan,” he said. The old command was gone. In its place was a man who had not slept.

“What happened?”

“It’s Ethan,” he said. “He’s in the hospital. Overdose. We found him in the garage last night. He’s alive. Barely.” In the pause that followed, a hundred feel-nothing trainings tried to rise in me—the ones that teach you how to keep your hands from shaking when the deck tilts. Grief is not a deck. It is a floor that disappears.

“I thought you were in Hawaii,” I said, dumbly.

“We were supposed to be,” he said. “He…stole money. We canceled to get him into rehab. He ran. He left a note.” The paper rustled. Dad’s voice dropped. “He said he was tired of being the failure. Said he was sick of living in your shadow.”

There it was—the story I had been cast in without audition. I wanted to argue with a boy unconscious in a hospital bed, to tell him the shadow was not mine, that I had never laid it across him like a blanket. But shadows are not about intent. They are about light and where it gets blocked.

“Where is he?” I asked.

“County General,” Dad said. “Can you…can you come?”

I looked up at the flag snapping smart above the auditorium roof and understood the choice in front of me. I could go on camera and be the version of myself people wanted to quote in headlines, or I could get in a car and be the person I had learned to respect when she looked back at me in the mirror.

“I’ll be there,” I said.

Hospitals smell like burned coffee and loss. I walked down the corridor in an immaculate uniform and tried not to resent the looks it bought me. Outside the ICU, my mother’s mascara had surrendered. My father’s hands were clasped like he was trying to hold two halves of himself together. “He asked for you,” my father said, as if the sentence were a gift he wasn’t sure he was allowed to offer.

Inside, the monitor’s rhythm tethered us to the room. Ethan looked younger than I remembered and older than his age, as if years had run through him too fast and left all their silt. He opened his eyes when I said his name.

“Missed your big day,” he whispered, his voice wrapped in gauze.

“I noticed,” I said.

He tried for a smile. “Saw you on TV. You looked…important.”

“Ethan,” I said, and my voice did a thing I hadn’t heard it do since we were kids and I had cleaned up behind him without being asked. “What happened?”

He turned his head away, then back. “I was jealous,” he said. “Dad made me that way. Every time you did something, he held it up like a mirror. Look, son. That’s what a Morgan is.” He swallowed. “I told him you didn’t want them there. I showed him…texts.” He closed his eyes. “I changed your day so they wouldn’t go. I thought if they missed it, if it blew up, maybe then—”

I stood up so quickly the chair scraped. “You forged texts?”

“I didn’t think—”

“No,” I said, and the steady officer voice came back because it was the only one that didn’t overturn the table and walk out. “You did think. You chose. You made me stand there and wonder whether my father stayed home because he couldn’t be bothered.”

He looked smaller than the boy who used to balance on the porch railing and laugh when I told him to come down. “I’m sorry.”

“Good,” I said. “Be sorry. Then be better.”

We said nothing for a while. The monitor kept time. In my head, I counted off the things I had learned to say in triage. Check the airway. Keep pressure on the wound. Stop the bleed. In the hallway, my parents waited for a verdict I couldn’t write.

“Rehab,” I said finally. “You go. You stay. You do the ugly work. You don’t call me for applause. You don’t call Dad for money. You call when you have one day, then two, then ten.”

He nodded, tears sliding without much drama. “Will you…visit?”

“When you are sober,” I said. “And when you’ve told Dad exactly what you told me.”

My mother stopped twisting the tissue and reached for my hand when I came out. It startled me more than the message had. “We didn’t know,” she said. “We should have called you. I was…ashamed.”

“Of what?” I asked. “Me?”

“Of how we raised you,” she said, voice small. “Of how we made everything a contest you didn’t ask to enter.”

My father looked older than his rank. “I was wrong,” he said. “About you. About a lot of things.” He glanced toward the room where his son lay returned to flesh and consequence. “I thought if I kept pushing him, he’d become—” He shook his head, words failing him for once. “You were never my shadow, Morgan. You were the only one of us walking toward the light.”

The elevator dinged down the hall. A nurse pushed a cart past and smiled at me the way people smile at uniforms that fit the story they want to believe about themselves. I looked at my father and mother and felt the edge of a road I had walked my entire life with my chin high and my eyes forward.

“Next time you have something to say to me,” I said, “say it before the medals go on.”

He nodded. “Yes, ma’am,” he said, trying for a grin. Then he straightened and, for the first time since I had left for Annapolis, saluted me without irony. I returned it.

Part IV — What Comes After

Forgiveness, I learned, is not a proclamation. It is a practice. It starts with small calls on Sunday afternoons that talk about tomato plants and the dog and Indiana weather instead of rank or regret. It continues with a brother who stays in rehab because this time the math of his life is finally adding up to more than an exit plan. It deepens with a mother’s handwriting on envelopes she licks closed herself, letters that begin Dear Morgan, we watched the sunrise today and end with words that look like blessings even if she never uses that word.

Work didn’t stop to make room for my healing. It rarely does. The following month, the Academy asked me to speak to a hall full of cadets about command and character. I stood at the lectern in a uniform that finally felt like it belonged to me and said the thing I wish someone had said in a voice I could have heard when I was nineteen and hungry.

“Leadership is not the size of your voice,” I told them. “It’s the size of your apology. It’s the way you treat the people who can give you nothing. It’s the choice to build a thing that will outlast your own name.”

After the applause, I stepped into the Maryland light, and there he was, my father in a suit, hair combed within an inch of its life, an old service pin back on his lapel. He looked at me like a man showing up to an appointment he had missed for years.

“I figured,” he said, “it was time I sat in the front row.”

I laughed. “You didn’t need an invitation.”

He took something from his pocket and pressed it into my palm—his dog tags, worn thin at the edges. The last time he’d given them to me, I had been a kid with a duffel bag and a spine of borrowed steel. “Back then,” he said, “I gave them out of pride. This time, it’s respect.”

I closed my fingers around the metal. It was cool, familiar, heavy. “Keep one,” I said. “I don’t need both.”

He shook his head. “You don’t know how much I needed to let go.”

Six months after the ceremony, the Dalton Center threw its first graduation. Twenty veterans crossed our makeshift stage—men and women whose gait had steadied, whose eyes had widened, whose hands no longer shook quite so much when they reached for certificates we had printed on the good paper. The flags moved in the breeze. Someone’s toddler clapped at all the wrong times. It felt right.

From the back row, Ethan watched in street clothes, sober eyes clear. He would start work at the center next week, folding towels and sorting supplies—small work that would remind his hands what purpose felt like. Beside him stood Emily in a crisp ROTC uniform. She had written me a note when she enrolled—You were right. Logistics. I want to keep things moving. I pinned a small compass to her collar and told her to keep north where she could find it.

After the ceremony, Dad came up the steps and did not trip on the last one. He looked out at the field where we had cleared brush with our own fingers and found the old flagpole under vines. “Your mother would have loved this,” he said.

“She would have told you to weed the west border,” I said.

He smiled and pulled in a breath that sounded like a man finally filling his lungs all the way. “I’m trying, Morgan.”

“Me too.”

We sat for a while under the old oak, and the quiet was not the old kind—the kind that used to split the room in two. It was a new quiet, made of the hum of post-ceremony cleanup and the murmur of volunteers finding garbage bags and the distant bark of a dog that thought it was in charge. Peace doesn’t arrive with trumpets. It arrives in plastic chairs and coffee in paper cups and a hand on a shoulder that used to flinch and doesn’t anymore.

That night, after everyone left, I walked the perimeter alone. The building’s walls caught the last of the sun and turned it into something softer. Inside the entryway, the new plaque shone:

Honor is not about revenge. It is about redemption.

I traced the letters, felt the cool groove of the carver’s work under my fingertips, and thought about how far a life can tilt without capsizing if you keep your eyes on the line where sky meets water. I thought about how forgiveness doesn’t erase; it redeems. About how the jacket you hand to a boy in a blizzard or the chair you step back from at a wedding can become the first line of a story you didn’t know you were writing yet.

On the drive home, the radio played a song my mother would have liked. I pulled over by the harbor and got out. The air off the water tasted like iron and rain. I held my father’s dog tags in my hand and spoke to the horizon.

“I did everything right, and you still didn’t come,” I said, because truth told in full loses its sting. “And I came anyway.”

The tags were cool against my palm. I slipped one back around my neck, placed the other in the glove box, and drove on.

Part V — The Win that Isn’t

Months later, the Navy sent a camera crew to do a “where are they now” segment. I told them they could film the center if they put the lights low and asked permission before they put a lens in anyone’s face. The host asked me what it felt like the day of my promotion when the seats had sat empty.

“Lonely,” I said. “But not as lonely as it would have felt if I had stood there having made myself small enough to fit in someone else’s story.”

He looked at me like he wanted a cleaner line. I didn’t have one to give him.

A week after the interview aired, a letter came with a return address I knew as well as my own. My mother’s cursive spilled across the page. We watched the show at the kitchen table, she wrote. Your father cried. He has been weeding the west border since sunrise.

I imagined him bent over the garden with his old sun hat on. I imagined him slipping a root out whole and feeling a satisfaction he hadn’t known when his pride had told him the only work that mattered came with a title.

The next day, a second letter arrived. This one from Ethan. I’m six months sober, he wrote. I got the night shift at the center laundry. I fold the towels like you taught me to fold flags. I understand now how both require respect.

I took both letters down to the dock and read them with my feet braced the way you brace yourself when the deck moves under you out of habit. A gull screamed and stole a sandwich out of a kid’s hand. The kid cried; then he laughed, because the world isn’t cruel so much as honest.

My phone buzzed. A text from an unknown number. The message read: You’re invited to keynote at the Academy on Leadership and Family. I smiled, not because the word keynote meant anything, but because the pairing finally did.

When I stood on that stage months later, cadets straight-spined in their chairs, I looked out at them and saw pieces of myself. The part of me that had wanted to salute my way into love. The part that had bargained with awards for approval. The part that had learned to choose the mission that mattered most when the budget and the orders and the needs didn’t align.

“There will be days,” I told them, “when you will wear a uniform and think it will save you. It won’t. What will save you is the person you are when the uniform is on the back of a chair.” I let my gaze catch on one face, then another. “There will be rooms where you will stand in front of empty seats and think those seats tell you what you are worth. They do not. You tell yourself what you are worth by where you stand when the room is empty.”

Afterward, a young woman approached me with a shaky urgency. “My father says I’m too soft for this,” she said. “He’s a chief. He thinks the Navy will eat me alive.”

“It will try,” I said. “Eat first.”

She almost laughed. “Do you…forgive him? Your family?”

“I forgive on Tuesdays at four o’clock,” I said. “I pencil it in and show up. Some weeks I reschedule. Most weeks I keep the appointment.”

That night, I slipped my shoes off beside the front door and hung my jacket on the hook I had installed myself. In the kitchen, I poured two mugs of tea. One I set on the table. One I took to the balcony. The phone buzzed where I had left it face down, and I let it buzz. The stars above the harbor squinted into view, stubborn as old sailors.

I thought about that day outside the auditorium with the hard sun and the sixteen missed calls and the letter from Daniel. He and I had divorced quietly, amicably. There had been no villain in that story—just two people whose clocks had spun in opposite directions too long to sync. He’d written once: I watched your ceremony from a hotel room. You looked…whole. I’m trying to learn how to be that. I told him I hoped he did.

Dad calls on Sundays. Sometimes he forgets what day it is and I call him on Mondays. Mom sends photos of the garden—sunflowers by the west border, dog paws muddy on the path, a tomato the size of a fist. Ethan texts me first now, stupid memes and long paragraphs about the residents who tell him their stories while he folds washcloths.

The three front-row seats at the ceremony aren’t empty anymore in my mind. They are met now by a line of cheap metal chairs at a veterans center where men and women sit with coffee cups and talk about grandchildren and pain and weather. My father sits there sometimes. He isn’t comfortable in crowds. He is learning. So am I.

If you were watching the broadcast that day, you saw a woman in a uniform accept a rank and nod at a country. What you didn’t see was the quieter work after—the phone calls returned, the papers filed, the planks replaced under an old flag, the way a brother learned to count his days in threes and then in thirties, the night my father stood in the rain and left flowers under my mother’s name and didn’t knock because some apologies have to be given to stone first.

Sixteen missed calls taught me something I would not have learned any other way: that I am not a lighthouse. I am a boat. I can turn my own wheel. I can choose a course that takes me into waters I had avoided. I can answer when the radio crackles, but I do not have to take every call. I can conserve fuel for the long runs.

We did talk, my father and I. We are still talking. On difficult days, I take out his dog tags and hold them in my fist until the edges dig crescents into my palm. On better days, I hang them over the corner of the mirror and let them catch light.

They are not a medal. They are a promise: that the next time I stand under a hard sun with cameras rolling, the person I need to recognize me will be there whether or not a single member of my family is.

Me.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. My Dad Publicly Shamed Me at My Sister’s Wedding — Until NATO Command Reserved Me a Seat.

My father told me, “This table is for family.” He said it in front of everyone — at my own…

CH2. I Was Rejected by My Father at His Wedding — I Tried to Make Peace, but He Chose Pride.

It was supposed to be a routine supply shift in Alaska — nothing special, just another freezing day in uniform….

CH2. My Dad’s Protégé Mocked Me at My Own Wedding — I Let Him Finish… Then the Truth Hit

At my own wedding, my father’s protégé stood up and called me “low class.” My father just sat there, letting…

CH2. I Broke Formation to Help a Child in the Blizzard — I Never Expected to Face the Admiral Himself

It was supposed to be a routine supply shift in Alaska — nothing special, just another freezing day in uniform….

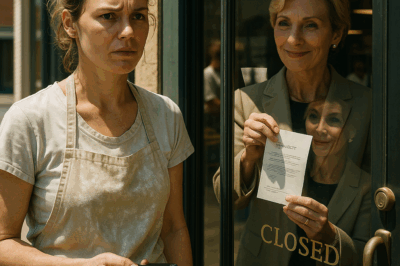

CH2. My Mom Smiled, “YOU SIGNED THIS, ALLISON.” Then Locked Me Out of the Bakery I Built, Until LAWYER…

At 17, My Family Kicked Me Out Over a Lie — Years Later, I Bought the Bakery They Tried to…

CH2. At 17, My Family Kicked Me Out Over a Lie — Years Later, I Bought the Bakery They Tried to Steal.

At 17, My Family Kicked Me Out Over a Lie — Years Later, I Bought the Bakery They Tried to…

End of content

No more pages to load