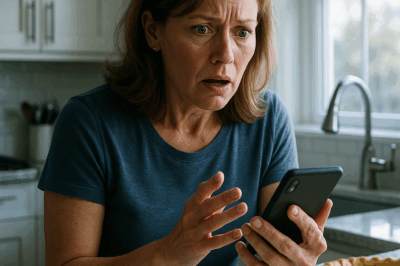

My Wife Texted Me at 2 A.M., “Can’t Talk Now, I’ll Call You Later.” By 2:10, She Walked In—Shaking.

Part I — Blue Light, Thin Air

Her text glowed in the dark like a lighthouse that didn’t want to save anyone.

Busy now. I’ll call later.

There are sentences that make sense at 2 p.m. and sentences that only make sense if you’ve already started lying. This wasn’t 2 p.m. And I’d been living with a feeling for months—the kind you can’t prove unless you’re willing to tear up floorboards.

I lay there on my back, phone hovering above my chest, the blue light painting my knuckles. The only sound in the room was the clock that hangs too close to our bedroom door. When we moved in, Leah complained about the ticking. Tonight it sounded like a metronome for something I didn’t want to write.

I typed: With who?

I didn’t press send. I didn’t need an answer to a question I already knew. I erased the message and typed instead: With whom? A joke only I would get. It made me feel petty and sane at the same time. I deleted that too.

Headlights skidded across the ceiling. Gravel whispered under tires. Front door hinge. Keys dropped on the console with the same little bell of metal on wood I’ve heard since we bought the table at a garage sale and argued about whether to sand it. Quick footsteps.

I lay still the way you do when you’re deciding who you are.

The door cracked. Light from the hallway edged the carpet. “Ethan?” she whispered, in the voice she uses when she doesn’t know what room she wants to wake.

I turned the lamp on.

Leah’s face was still flushed from the outside air, curls damp where the mist collects in them when the temperature falls. She had that after-midnight makeup—rubbed eyes, bitten lip, a line at the corner of her mouth like she’d been working hard at a smile for hours. She looked surprised that I wasn’t asleep. Then she looked like she wished she had been.

“You’re home early,” I said. My voice sounded like a different person’s: decent, almost bored.

“Yeah. Plans changed,” she said, brushing hair off her forehead with a hand that shook. Her purse slipped from her shoulder and hit the floor. I smelled her perfume—too much—and underneath it a faint, clean cologne like the inside of a new car.

“Change at two in the morning?” I asked.

“It wasn’t that late,” she said. “We were just… busy.”

“That’s what your text said,” I said, and the room filled up with all the things she didn’t want to say.

She tried a laugh. It didn’t make it into her eyes. “Ethan, come on. Don’t start this again. It was just a night out.”

I sat up. The floor was cold under my heels. “Who were you with?”

“The usual. Sarah. Jess.”

“Stop,” I said, and the word came out quiet enough to make her flinch.

Her mouth opened, then closed.

“Who is he?” I asked, like asking a weather report: indifferent to the storm’s feelings.

She shook her head hard, tears sudden in her eyes, the kind that show up to try to freeze whoever you’re talking to in place. “I made a mistake,” she whispered into her hands, and the last of the scaffolding collapsed.

“What kind of mistake?” I asked. The kind with a first name? The kind with a schedule? The kind with miles?

She stared at the carpet. Silence can be a fact. I felt all the times I should have asked sooner thud down around us like books from a shelf.

I moved past her toward the window. “Funny,” I said to the glass. “I’ve known something was off for months. The phone you hug like a life preserver. The late nights. The wine that doesn’t smell like your wine. I told myself I was paranoid because men who destroy good things often start by being scared of wind.” I turned around. “And yet.”

She was crying hard now. “Please don’t give up on us,” she said, and I felt something in me go numb and efficient—an organ that had been waiting for an excuse to perform.

“You already did,” I said.

Her phone was on the dresser. She had forgotten to lock it—panic makes the best security policy. I scrolled until the screen became evidence instead of story.

Matt (Work): Last night was perfect. I can still smell your perfume.

Leah: Stop. You’re going to make me change it.

Pictures taken at angles I recognized from our kitchen and from restaurants I have paid for. Private jokes built out of words she once used with me. The thread was long enough to have seasons.

“Does he know you’re married?” I asked. Leah nodded once, the kind of nod people do when denial is no longer available.

I put her phone down like it was a glass that wasn’t mine to wash. “I’m going to a hotel,” I said. “You can have the bed.”

“No,” she said, stepping toward me like she could rearrange time with her hands. “Don’t go. We can fix this. I’ll do anything.”

“Anything?” I asked. “Then tell me why.”

She wrapped her arms around herself like she was cold. “I felt invisible,” she said. “I wanted to feel something.”

Invisible. The word lodged under my ribs like a splinter that would take months to work out. I opened the door, and when the latch caught the frame it sounded like the truth landing.

My phone buzzed while I stood in the parking lot of a three-story hotel whose sign loses a bulb every four months. Please come back. I’ll explain everything. She already had.

I turned off my phone and slept like a person who had decided not to pretend.

Part II — The Binder

The hour before dawn is when things are most honest. A motel room smells like cleaner and air conditioning and loneliness in a way that feels refreshing. I lay there staring at the ceiling tiles and knew that the version of me who goes home and forgives because I am good at forgiving was the same version who would be back in this same room in six months. I let him go.

I went home at 8 a.m. to shower and collect clothes and my dignity. Leah was at the kitchen table with a face that wanted me to think it hadn’t slept. She reached for my sleeve. “We can—”

“Don’t,” I said, and brushed past.

I built a pot of coffee strong enough to restart a heart, set it on the counter, and got to work. Not on saving us. On saving me.

I opened a new document and titled it Timeline. The engineer in me wanted facts, not feelings. I went to the cell carrier’s site and downloaded my usage data—hers too, because the bill is in my name. I pulled calendar invites from her shared account. I checked our smart garage’s open/close logs. I requested rideshare receipts from her email and my own. I placed it all in a bound presentation folder I use for client design reviews—the black one with the silver clip. I printed the text thread I wasn’t supposed to see, not to punish her but because paper behaves under pressure in a way screens don’t.

It took two hours to assemble the binder. It took three years to put off needing it.

At noon, I called an attorney whose name I got from a coworker who is happily divorced. “You are angry,” she said over speakerphone, “but that’s not your job today. Your job is to document and to decide what you need.” She told me two things I wrote on a sticky note and tucked into the binder’s front sleeve:

-

No Contact with AP (affair partner) is non-negotiable if you consider reconciliation. Written. Signed. Enforced.

Transparency or separation. No limbo. Decide a timeline. Hold it.

The door opened. Leah walked in like someone who didn’t know how doors work anymore.

“What is that?” she asked, motioning toward the binder. She tried for contempt. She landed on afraid.

“It’s the truth,” I said.

We sat across from each other at that table we built together the summer we couldn’t afford to go anywhere and learned how to sand corners gently. I slid the binder across. “We can talk,” I said. “But we will use the same map.”

She turned pages. Her tears changed. Not manipulative now; chemical. “I’m sorry,” she said into her palms. “I’m so sorry, Ethan. I don’t know what happened to me. I didn’t mean to—”

“You meant to,” I said, not unkindly. “You just didn’t mean to get caught.”

She nodded. It was the first kind thing she’d done for me in a year.

“I need three things,” I said. “Then I need ninety days.”

She looked up. Hope is a terrible historian. It flooded her face. “Anything,” she said too fast.

“No Contact begins now,” I said. “You will draft a letter to Matt that I will approve. You will send it while I watch. It will be concise and undramatic. Then you will block him. If he contacts you, you will forward it. You will not respond. If you violate this, we are done regardless of the other two items.”

She nodded, already reaching for her phone like a person eager to be good for five minutes.

“Transparency,” I said. “You will hand me your phone every evening at 9 p.m. You will unlock it without complaint. You will not delete anything. I will not go hunting through your soul. I will glance long enough to know if the wound has scabbed. You will share your location with me. I will not abuse it.”

She nodded again, slower now.

“Counseling,” I said. “You will schedule individual therapy for yourself. We will schedule couples therapy together. You will attend. Not to present your case, but to discover your self-respect.”

“And then we are okay?” she asked, voice small like the first week we moved in and the pipe under the sink burst and she cried because the rug got wet.

“And then,” I said, “I will leave for ninety days.”

Her face did not know where to put that many emotions. “Leave?”

“I am not punishing you,” I said. “I am not going to stay and be your warden. That is not a marriage. I am going to my brother’s for three months. You will use the house to figure out who you are when no one is watching you drown us. If, at the end of ninety days—if you have kept No Contact, practiced Transparency, and showed up in therapy—the counselor will tell me if I should come home. Not you. Not me. Someone who knows what healthy feels like.”

She stared at me a long time. Eventually she nodded, because what else can you do when someone offers you a bridge and a stopwatch?

“Draft the letter,” I said.

She typed.

Matt,

This ends. I betrayed my husband and myself. You were a part of that. I will not speak to you again in any capacity. Do not contact me.

—Leah

It was almost good. I deleted betrayed my husband and myself and typed I betrayed my vows. Sentences are scalpel work. She pressed send. It felt both ridiculous and sacred to watch three words become a door: Do not contact. Then I watched her block him. Then I packed a suitcase and put my binder in it.

At 7 p.m., I put my key on the hallway table and left.

Ninety days is either a blink or a lifetime. It depends on whether you’re counting.

Part III — A House I Wasn’t In

My brother, Aaron, is a firefighter. His living room smells like coffee and wet dog and a clean kind of exhaustion. We’ve never hugged much. That week we started.

The first thing he said when I walked in with my suitcase was, “You sure?” The second thing was “Beer?” The third thing was “Sit.” He turned on the TV and then muted it, because sometimes a brother is a person who knows that your brain needs noise and your heart needs quiet.

We didn’t talk about Leah for a week. We stacked wood. We grilled sausages in the snow like lunatics. We drove to the deli we loved as kids and argued about coleslaw like it mattered. I slept on a couch that remembered thirteen Thanksgiving naps. It held me like a person.

Leah sent two texts a day. Morning: a photo of a coffee cup and a location pin attached to a therapy office. Evening: a screenshot of her screen time, her phone on the table like an offering. I did not respond. I added entries to a little notebook. Day 12: no contact. Day 23: no contact. Day 34: HR email.

On Day 34, an email from Leah arrived with the subject line: Work. Her company’s HR department had policies. Affairs with colleagues weren’t banned; deception that affected teams was. Leah had confessed. Matt had been transferred to another division in another city. Leah had requested a lateral move. People love drama. Offices love policy. It was the first decision she made that felt like an adult following a map off a cliff she built.

On Day 41, she sent a photograph of a Post-it on a fridge that was not ours. Book club tonight. Home at nine. She had put the note there for herself, not for me. It was the first time I saw her planning a life instead of planning a lie.

On Day 57, she wrote:

Today I told the story out loud in therapy without making myself the victim. It felt like swallowing nails and then being able to breathe.

On Day 70, she sent nothing. My chest went cold. I stared at my phone like it was an altar refusing to light. At 9:17 p.m. she wrote:

No message tonight because I forgot my phone in the car at counseling and locked myself out of the building after. I sat on the curb for thirty minutes thinking about you and your binder. I realized I want to be the kind of person who never needs one. I want to earn a boring life.

I smiled into Aaron’s orange chair like an idiot.

On Day 83, my attorney called. “How are you?” she asked.

“I don’t know what that means anymore,” I said.

“Good,” she said. “It means you’re not confusing the absence of adrenaline with happiness.”

“Is happiness just the absence of adrenaline?” I asked.

“Sometimes,” she said. “Sometimes it’s pancakes.”

On Day 90, I went home.

The house was clean in a way that had nothing to do with countertops. The binder sat on the table with a sticky note on it: This brought us to the edge. Can we build a new map?

Leah stood in the kitchen with flour on her hands. There were pancakes.

We didn’t touch for a long moment. We did something harder. We sat. We looked at each other like people who had seen a hurricane choose another city and still didn’t forgive the sky. I opened the binder and took the sticky note out. I wrote, No more binders and slid it across. She nodded and cried and didn’t grab me—another new map.

We talked. About grief. About the boredom that comes after joy if you don’t tend it like a garden. About power and attention and all the places a person goes when they forget they are loved. She didn’t claim invisibility this time. She said, “I abandoned myself and took you with me.” I said, “I used competence like a shield and called it virtue.” We both said, “I’m sorry,” in a way that didn’t beg for pardon.

I didn’t move back in that night. I told her I wanted another week of sleeping without clocks. She said okay. She didn’t collapse or seduce or rage. She said okay and handed me a pancake wrapped in foil like a treaty.

A week later, I moved back into a house that was not the same house I left.

No triumphant montage. No slate wiped clean. Just a calendar full of therapy appointments, weekly check-ins without phones, one shared playlist that wasn’t ours until we added new songs, and a rule we made together:

We will not save up conversations for after midnight.

Part IV — When the Phone Buzzed Again

Three months after I moved back, I was at my desk when my phone buzzed at 2:03 a.m. Busy now. I’ll call later.

I smiled. Then laughed, quiet so I wouldn’t wake the dog that isn’t ours but keeps sleeping on our porch like he knows we needed something to take care of that wasn’t breakable.

It was a wrong number from a county on the other side of the state. I could have ignored it. I didn’t. I wrote back: Wrong number. Hope you get home safe. Then I put the phone back on the nightstand and turned toward the woman breathing steadily next to me.

Leah stirred. “You awake?” she asked, words thick with sleep.

“Yeah,” I said.

“Nightmare?”

“No.”

“Good,” she said, and slid a foot along my ankle, a small apology for all the nights she slid away from me and I pretended not to notice. I reached for her hand under the blanket. She laced her fingers with mine the way a person holds a rope when they’re done drowning and ready to climb.

In the morning, she set a cup of coffee by my elbow and kissed my shoulder. “HR wants me to lead a training on ethics,” she said, rolling her eyes. “Apparently I’m a cautionary tale. They said I can say no.”

“What did you say?” I asked.

“I said yes,” she said. “If I have to be a story, I want to at least tell it correctly.”

I nodded. “Tell them about the binder,” I said.

“And the pancakes,” she said.

“And the ninety days,” I said.

“And the fact that ‘invisible’ was always a trick word,” she said.

We ate breakfast like rich people—time-rich, honesty-rich. The house sounded lighter. Even the clock ticked like it was counting something other than mistakes.

Sometimes people ask me if we’re “healed.” I tell them healing is a verb, not a country. You don’t arrive. You walk. Some days you limp. Some days you lie down in the grass and decide the sky can count without you for a while.

They ask if I regret not blowing it all up—moving trucks, locks, the clean slice of a closed life. I think about the night I could have. I think about the first time Leah passed me her phone at 9 p.m. without me asking. I think about all the marriages that die because pride doesn’t know the difference between a broken bone and a bruise.

No, I say. I don’t regret choosing the harder map.

This story doesn’t end with vengeance or a new love on a cliffside somewhere. It ends here, with a kitchen table that learned how to hold weight again, a binder in a drawer with a sticky note on it, a dog that may or may not be ours, and a phone that sometimes buzzes at 2 a.m. with someone else’s panic and reminds me to be glad for the silence in my own house.

If you’re the one lying awake counting the seconds between a text and tires on gravel, here is what I learned when the door opened and the lamp came on:

Ask for a map that both of you can read.

Draw your lines before you need them. Carry them in your pocket.

Choose a timeline. Pain loves forever; healing needs a deadline.

Decide what forgiveness is for you. Not forgetting, not erasing—permission to stop carrying a person like a wound.

Make pancakes. It won’t save you. It will give you something to do with your hands while your life becomes honest.

We still keep the rule—no saving up conversations for after midnight. When the clock ticks loud, we speak before the hour makes liars out of us.

And when the phone buzzes with a text that would have destroyed me a year ago, I turn off the light, roll toward the person who stayed, and sleep.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. My Parents Moved to Barcelona and Left Me With My Sister’s 6-Month-Old Baby — Then Came Back…

My Parents Moved to Barcelona and Left Me With My Sister’s 6-Month-Old Baby — Then Came Back… Part I —…

CH2. At her family reunion, someone joked: “Are you two happy together?” My wife laughed: “Happy? I regret this marriage every day!” her family burst out laughing -until I smiled and said, “Me too. That’s why I’m ending it -today.” The room went silent.

At her family reunion, someone joked: “Are you two happy together?” My wife laughed: “Happy? I regret this marriage every…

CH2. When I threw away the child seat my mil gave us, my hubby yelled, ‘Mom gave that to us!”

When I Threw Away the Child Seat My MIL Gave Us, My Husband Yelled, “Mom gave that to us!” Part…

CH2. Ten Days Before Thanksgiving, I Found Out That My Daughter Was Planning To Humiliate Me…

Ten Days Before Thanksgiving, I Discovered Something That Shattered My Heart — My Own Daughter Was Plotting to Humiliate Me…

CH2. On My Birthday, I Learned They Took More Than Just My Gifts — What Happened Next

On My Birthday, I Learned They Took More Than Just My Gifts — What Happened Next Part I — The…

CH2. My Dad Removed Me From the $30K Dubai Trip I Funded—To Give My Spot to My Brother’s Fiancée

My Dad Removed Me From the $30K Dubai Trip I Funded—To Give My Spot to My Brother’s Fiancée Part I…

End of content

No more pages to load