My wife and my brother were rushed to the hospital where I work, both unconscious. When I tried to see them, the doctor said, “You must not look.” When I asked, “Why?” the doctor replied…

Part I — The Corridor Where Clocks Don’t Tick

The hallway outside Trauma bay 3 never truly sleeps. Even at 2:17 a.m., with the vending machine humming like a cranky animal and the fluorescents bleaching the linoleum bone-pale, that hallway is awake. I know the pitch of its alarms, the weight of its silences. I’ve closed sternums here. I’ve told fathers that their sons did not come back. I am not easily shocked.

The code paged overhead didn’t say names—only ages, vitals, ETA. Still, I knew. The city is small at that hour, and the dispatcher said eastbound rollover, two victims, early thirties, and the world put a hand on my throat.

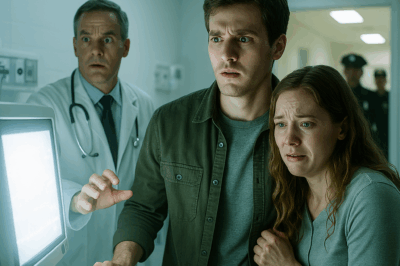

I was already in a lab coat when the gurneys appeared, pushed fast—nurses at the rails, respiratory behind. Two stretchers, side-by-side in a choreography that felt cruelly intimate. One carried my wife. The other carried my brother.

Their faces were gray with glass dust. Blood had found the seams of their clothes. An oxygen mask fogged with each shallow breath. I moved before I could think the word how.

“Trauma three,” I said, as if assigning them to a room could turn chaos into a list. I followed the carts. The doors sighed open. The air inside tasted metallic.

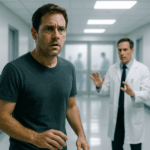

“Nick,” someone said—our night trauma attending, Rob, a good man whose fingers have learned how to pull lives back from edges. He stepped into my lane with an arm extended, palm soft against my chest. “You must not look.”

It didn’t register. “They’re my family,” I said.

He lowered his voice so the room wouldn’t hear it fray. “That’s exactly why. Once you see, you can’t unsee.”

It was the kind of warning we give to protect people from images that will colonize their sleep. But I live in those images. They’re my job. They didn’t scare me. I stepped around him.

The curtain was half-drawn between the two trauma beds. The OR light washed everything to a useless, surgical white. And then I saw what he meant.

They were unconscious, but their hands—his right and her left—were clasped across the gap between beds, fingers interlaced the way sleeping children hold onto the world when they dream they are falling. Their knuckles had blood on them that wasn’t all their own. Where her wedding ring should have sat, there was a clean, pale band of skin.

A nurse at the head of the bed saw my face and quietly turned the monitor away, like she could protect me from numbers. The room contracted to the size of a single hand.

Rob’s voice came from somewhere with gravity. “You see the crash,” he said gently. “I see the crash. The rest of them will see the other thing. And they’ll talk. You don’t want to be in the break room hearing this story as gossip.”

My mouth remembered how to say two words: “Do your best.”

I backed out until the curtain swallowed them both. The hallway was too bright. I leaned my forehead against the cold tile and tasted salt. Somewhere down the bay, a chest tube clattered into place. A respiratory therapist told a patient she was doing great. Outside the automatic doors, the city hadn’t even noticed our night.

I lifted my head, straightened my coat, and went to an empty alcove where we keep the blankets. I sat on the radiator and watched a scratch on my shoe. I did not go back in.

Part II — Triage Is a Kind of Arithmetic

She lived. He lived. Trauma is honest that way—sometimes indifferent, sometimes merciful. It gave me both survivors, which felt, at two in the morning with his hand holding her hand on a bed I knew the serial number of, like a complicated kind of cruelty.

I did not touch their care. I am a cardiothoracic surgeon, not trauma, but there are rules beyond specialty. We do not operate on our own if we can help it. We do not write our family’s orders. We do not open a chart and violate a boundary we will need later.

But boundaries are dreams in a hospital. We live by loops and proximity. I knew what their scans showed from the way the nurses walked out of the room. Broken ribs, a femur fracture, a concussion, a splenic laceration that bought a night in the ICU and a second blood transfusion. Nothing that would need me to saw bone. Everything that would need me to hold back.

At five in the morning, when they were both stabilized, I went to the staff bathroom and washed my hands as if I’d been the one touching them. I watched blood I hadn’t earned circle the drain and said a sentence out loud to nobody: “This is the last time I am surprised.”

My wife—Lena—is good at being loved. She grew up as an only child in a house where people did not say the hard thing, and it taught her the power of smiling at a storm until it stops embarrassing itself and moves on. My brother—Tom—was the kind of kid who could talk a streetlight into staying green. He is a physical therapist. He can put a shoulder back where it belongs with fingers that know how to listen to tendons.

A month ago, they were both in my kitchen at the same time, laughing at one of his stories while he stole food off her cutting board. She rolled her eyes at me. I kissed her temple. It felt like a family. Now I watched a curtain billow and thought: what else did I miss?

Rob found me by the vending machines peeling the foil off a granola bar like a surgeon prep. He leaned against the wall. People respect doors more than corridors, so we speak in corridors when we need to tell the truth.

“We intubated and extubated both,” he said, neat and clinical. “She’ll be on a PCA pump for the ribs. He needs traction on that femur until ortho pins it in a day or two. No spinal involvement. Lucky.”

My face didn’t trust the word. “They were holding hands,” I said.

He nodded once. “They were.”

The machine ate my dollar and refused to drop the peanut butter crackers. I did not feel like laughing.

“You going to go home?” he asked.

I shook my head. “I have rounds at eight.”

He didn’t tell me to sleep. He has known me long enough to stop wasting language that way.

When I finally went in, mid-morning, Lena was foggy with pain meds. Her hair was cuffed to her forehead with dried sweat. It is a delicate thing to touch someone you love when every inch of them is borrowed by medicine. I touched the bed rail lightly.

“Hi,” I said.

Her eyes found my voice and then my face. I watched the recognition travel through shock into apology so fast it made her hands flutter like she was underwater. “Nick,” she whispered, then swallowed. “You saw…?”

“Triage,” I said evenly. “Saw enough.”

“I—” She started to say it wasn’t what it looked like and stopped, to her credit. She has always been smart. She looked at her bare ring finger, then at the left side of her chest where the ECG stickers made pale flags on skin the color I had called home for ten years.

“We had a fight,” she said instead. “We were driving too fast. We… he wanted to— talk. It got stupid. The car—”

“Don’t,” I said, a new kind of calm in my voice that both of us heard and did not know.

Tears gathered dutifully like they had RSVP’d to this moment weeks ago. “I’m sorry,” she said, the first honest sentence.

“Me too,” I said, and left before pain meds could turn this into something we’d both use later as an excuse.

Tom’s room had the stupid blue poster with the ocean and the word BREATHE on it like anyone has ever obeyed a command written in sans serif. He was propped up, eyes glassy. He tried to smile and got halfway.

“Doc,” he said, because he hasn’t called me Nick since I got my license. “Wild night.”

I looked at his leg in traction and the bandage on his temple. Somewhere in him is the kid who broke his arm on the monkey bars because he wanted to impress a girl and grinned while his forearm bent like a new hinge. That kid was less complicated. This man searched my face for a marker fewer men than you think have: mercy.

“We didn’t mean—” he began, then winced. Honesty is a muscle; he hadn’t worked it much.

“You crashed your car,” I said. “Drive careful next time.”

His mouth tugged sideways—part contrition, part relief. He thought he’d gotten away with something. He mistook shock for generosity. This is the thing about betrayal: it makes people mistake distance for grace.

I nodded to the nurse on my way out. She touched my forearm, a tiny human gesture lost under a fluorescent life. I went back to my office, sat at my desk, and opened my laptop. Not because I wanted to write an operative report. Because I needed to think in bullet points so I wouldn’t think in images.

I opened my email and typed five letters into the search bar: LENA. Hundreds of messages came up. I filtered by attachments. Receipts, hotel confirmations, a gym membership my wife doesn’t use attached to an address she’s never told me. One email contained a PDF that made me stop breathing outdoors.

Hotel Grand—early check-in confirmed. The room number circled by a sloppy digital markup. A note below: “Always ask for that one.”

I printed it. I am a man who believes paper has weight and should be asked to carry it.

Then I typed TOM into the search bar. My brother has borrowed money from me four times in ten years. Within my inbox lived the IOUs he forgot he sent. I printed those, too. Leave it to a surgeon to turn heartbreak into a chart.

Part III — Evidence Is a Language

There are things surgeons do well and things we do poorly. We are excellent at closing. We are terrible at grieving. When my father died, I tried to suture my mother’s silence with casseroles and checklists. When Tom went to college, I labeled his boxes with their destination not their contents. So it shouldn’t surprise me that when my marriage cracked, I built a file.

I requested phone records. Heavily redacted, heavily illuminating. Texts between my wife and a number saved as Eva that didn’t exist in Lena’s friend list. A call to my brother’s landline turned into a 40-minute conversation after midnight on a Sunday. A Venmo payment from Lena to Tom with the memo “laundry.” I love my wife. I have never seen her wash my brother’s shirts.

I sat at the kitchen table at midnight and slid the pages into a white envelope because I needed something to hand to the truth.

The next night, I waited until visiting hours ended. Hospitals are good at protecting patients from crowds. They are less good at protecting them from themselves. I stood in the doorway of Lena’s room with the envelope. She looked small against all that white. Pain makes people honest in flashes. I counted on that.

“Read this before you visit Tom in the morning,” I said, and placed it on her lap.

Her hands trembled even before she opened it. Every photo she pulled out took color from her face like a tide retrieves its water. She whispered my brother’s name as if it were both confession and curse. She didn’t notice Tom standing in the doorway on his crutches, the other half of her sentence. His breath hitched. He has always hated being told the truth about himself.

“You told me he didn’t know,” she said without looking up.

I could have said, You told me you didn’t lie, and we would have been even. Instead, I watched realization roll through the three of us like an aftershock. It is one thing to betray a stranger. It is another to violate the only pre-existing story your family knows how to tell about itself.

She started to say I’m sorry and stopped. She looked at me. I didn’t nod. Sorry is a tourniquet. It slows bleeding. It doesn’t repair tissue.

The next morning, I transferred them. Different wings. Different teams. No shared therapy. To the staff, it was by-the-book risk management: keep the narratives that enable patients out of each other’s rooms. To me, it was the cleanest cut I could make that would not harm them physically and might save the rest of us.

My mother called from Florida three days later and asked why Tom hadn’t returned her messages. “He’s asleep,” I said.

“He never sleeps,” she huffed.

“Now he does,” I said.

I did not tell her her two youngest had been pulled from a bent cage holding hands like children at a sleepover. I did not tell her my wife’s ring finger had a tan line and no ring. I told her to call him when the discharge papers showed a date.

A week after the crash, Lena was discharged. She packed slowly, as if the act of folding shirts could delay a consequence. She tried to call me twice that day. I did not answer. She tried to call me a third time and texted please just talk. I wanted to; my thumbs miss my wife. I watched the typing dots appear and disappear like a heartbeat struggling in telemetry.

Tom was discharged two weeks later with a femur that would set and a limp he would keep for months. He came to my office and tried on regret like a jacket he wasn’t sure fit. “She left me,” he said. No hi. No you look tired. No I am sorry I tried to steal your life.

“No,” I said. “You left yourself. She just noticed.”

He blinked. The muscles around his mouth tried to keep up with a new language. He started to say “Nick,” the way he has always said my name when he wants me to be a brother and not a surgeon with a file. I let him hear my silence instead.

As he reached for the doorknob, I added, “Don’t visit Mom and Dad. I told them you needed rest. They think you are somewhere quiet. Let them be right about one thing.”

He nodded, which is as close as Tom comes to thanks. He closed the door softly. That’s the thing about some men: they can break a life loudly and leave a room gently and think they are balanced.

Part IV — Scar Tissue Learns Its Own Weather

There’s a rumor in certain break rooms that surgeons are gods. We are not. We are janitors with expensive tools. We clean up the world’s mess and try not to make ours worse.

Six months after the crash, the hospital smells the same. People still code at 3 a.m. Sometimes the chest compressions go well. Sometimes they don’t. I do my job. I eat cereal at my kitchen island with a spoon that used to share a drawer with my wife’s favorite knife. I wear my wedding ring. Not because I am pretending. Because I need the pressure of metal to remind me that trust is a structure that fails the way bridges do: slowly at first, then all at once.

Lena moved out quietly. No slammed doors. No hail of accusations. She left a note on the table that said I loved you and I was lonely and I am sorry in that order. Each sentence was a fact. None felt like a stitch.

My parents learned pieces. Families are poor at complete pictures. My mother asked why Tom and Lena weren’t coming to Thanksgiving anymore and then answered her own question with a story that required nobody to be wrong. My father listened to football. I brought pie. The word brother walked past both of us like a cat who had recently scratched someone and needed to be fed.

I did not become a monk. I am not a martyr. I am a man with a house that echoes sometimes. I fixed a leaky faucet and felt a stupid surge of pride because my wife hadn’t asked me to but I wanted to. I set a table for one and then added a second plate because I am practicing for a future that might not eat alone.

One night, Lena texted Can we talk now? and I typed Not yet and set my phone down like an instrument on a tray I’m not ready to pick up.

Tom sent a photo at 1:00 a.m. of his shadow on a sidewalk and the words sober 90 days. I wrote good and pressed send and did not add anything about the fact that being sober doesn’t treat arrogance the way antibiotics treat strep. He has to do that part on purpose.

Sometimes I sit in the trauma hallway after a long case and watch new families get made and unmade at the speed of lights turning from red to green. When a hand slips into another hand across a bed, I look away. I have learned that some kinds of love are not meant to be witnessed by me at that distance anymore.

Rob, the attending who stopped me that night, found me there last week and sat on the radiator the way I had back when the envelope was still white and full.

“You okay?” he asked.

“Define,” I said.

He glanced down the hallway. “Sleeping regularly. Eating food shaped like food. Not operating on your own ghosts.”

“I sleep in piles,” I said.

He grunted. For a surgeon, that is empathy.

“I told you not to look,” he said.

“You did,” I said.

“You looked.”

“I did.”

“You regret it?”

I thought about that a long time. When surgeons are quiet, it scares some people because they think we’ve run out of facts. The opposite is true. We are touching one and deciding where to put it.

“No,” I said. “I regret that I had to.”

We sat until a nurse walked past us and said, “You two doing okay?” in the tone that means I will drag you to Employee Health myself if you give me the wrong answer.

“We’re talking,” I said.

“Make it quick,” she said, “the vending machine only respects exact change this week.”

We laughed because sometimes medicine is only possible if you can figure out which part of a vending machine is tragic and which part is a joke.

Part V — The Line I Would Not Cross (And the One I Did)

People ask if I wanted revenge. The answer is so unsexy it sounds like lying: I wanted control.

I dated the envelope with the photos the night my house felt emptier than the trauma bay. I put it back in the drawer because having it out on the counter made the kitchen smell like iodine.

I changed the beneficiaries on my life insurance because I am a man who climbs tall things with knives in his hands and I have learned not to be stupid.

I didn’t file for divorce immediately. This makes some people clutch at etiquette. They need a clean arc, a certain righteousness. I am too tired for public morality. I was waiting for the wound to tell me whether it wanted to close; sometimes a suture does more damage than a scar. I gave us a season.

In that season, Lena tried twice to meet me where the damage was. We sat in a park under a tree that does not care what humans do beneath it. She cried and did not beg. I did not reduce her to the worst thing she has done. We made a list of hard truths in the Notes app on my phone like teenagers threatening to become adults:

We were lonely in the same house.

You didn’t tell me you were starving.

I stopped cooking and called it being too tired.

You made me god in rooms where I wanted to be human.

I loved you in the way I was taught, not in the way you needed.

We looked at each other over so many commas and a few periods. We are not enemies. We are not okay. We are not on fire. We are not a pair of hands locked on a bed we do not own. We are people who once entered a kitchen at the same time because the soup was ready, and I still don’t know what to do with that tenderness.

The line I would not cross was cruelty. The line I did cross was silence. I told her I would not carry this by myself and call it stoicism. She nodded as if I had given her permission to build a life beyond me without my blood on it. We are not ready for a court docket. We are ready for separate keys.

Tom and I do not speak often. He sends progress like postcards: Paycheck. Sponsor found. Ran three miles. With each message he is reminding me who he wants to be when he isn’t the man in a doorway watching a woman read an envelope he earned. I learned early not to hold my breath when my brother promises. I have relearned that with oxygen.

My parents finally asked me what happened in the tone parents use when they suspect they cannot handle your answer. I said a sentence my therapist taught me: “Something broke. We’re fixing what we can and living with the rest.” My mother pursed her lips. My father patted my shoulder like I was a dog who had almost caught a ball once. Families are their own species.

Part VI — The Question and the Answer Nobody Likes

“Would you do it all over again?” a scrub nurse asked me, not about my marriage but about that night in the trauma bay, about looking.

I told her the truth: “Yes.”

She raised an eyebrow. “Even knowing?”

I nodded. “Knowing is how I sleep. Or how I don’t. But it’s how I live.”

The hospital hums. Lives unspool here. We catch what we can. In the hallway outside Trauma three, I sometimes stop longer than necessary and think about hands. The way newborns grip a finger as if they’ve been practicing in the womb. The way old couples walk out the door holding each other the way the body remembers ladders. The way two people I loved reached across white sheets toward each other as the room tried to pull them back to separate rails.

“Don’t look,” Rob had said. He was trying to keep a friend from swallowing glass. It was kind of him. I looked anyway. That image is a stone in my pocket. I take it out sometimes and remember that love, like any organ, can rupture under pressure you didn’t know you were applying.

I kept my ring on. Not because I fancy myself tragic. Because it suits me to remember that even surgeons cannot save everything, and that choosing when to close and when to leave a wound open is the work. In every sense.

Six months later, Lena sent a message: “Can I sign up for the waitlist at your cardiopulmonary rehab?” It was a joke and not. I wrote back “We accept all major insurances. And contrition.” She wrote “One of those is in network.” I smiled like a man who has finally learned his own weather.

I went home and made soup. The kitchen echoed and then didn’t. I ate standing at the counter. The refrigerator hummed approval. I washed the bowl. I sat in the dark and listened to the rain on the window until the house and I were certain the other one wasn’t going to leave.

Some nights, that image of two hands finds me. I let it sit. It is not a monster. It is a portrait. It asks for acknowledgment, not indulgence. I tell it I see you and it gets up and leaves the room.

Love isn’t sacred. It is human. Contracts are honored by humans or broken by them. Scars do not indict the knife—they testify to what survived after.

I still walk the hallway where clocks don’t tick. When someone says Don’t look, I take their hand and stand beside them, feeling the weight of what they are choosing not to see, the way you stand with a patient who refuses a treatment you know could save them. You do not bully. You bear. You say I’ll be here if you change your mind and you mean it.

And when a hand reaches for another across a bed and finds it, I look away. Some things are not mine to witness anymore.

Outside, the city keeps its secrets. Inside, the vents carry stories we pretend not to hear. In a drawer at home, there is an envelope, now empty. I kept it, not for the paper, but for the shape it taught me my life could take when cut cleanly.

When the hospital goes quiet around three in the morning and the monitors are a lullaby for the stubborn, I sometimes whisper something to the air that lives between grief and grace:

This time, I didn’t miss anything.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. My sister emptied my accounts and vanished with her boyfriend. I was heartbroken until my 9-year-old daughter said ‘mom, don’t worry. I handled it then, days later my sister called screaming…

My sister emptied my accounts and vanished with her boyfriend. I was heartbroken until my 9-year-old said, “Mom, don’t worry….

CH2. For My DAD’S BIRTHDAY, I Gave Him A Used BMW. But He Rolled His EYES, “You Couldn’t Even Afford…

For My DAD’S BIRTHDAY, I Gave Him A Used BMW. But He Rolled His EYES, “You Couldn’t Even Afford New.”…

CH2. “My husband told his mother, ‘I’m leaving her. I can’t live with a woman who earns less than me.’ I agreed to everything he wanted. A month later, his lawyer called him, his voice shaking. ‘Why didn’t you tell me about this?’ he asked. My husband froze- he finally understood what I’d never said.”

“My husband told his mother, ‘I’m leaving her. I can’t live with a woman who earns less than me.’ I…

CH2. My Family Said “There’s No Room For Your Kids” Every Holiday. Until I Showed Them Space…

When my family said there was “no room” for my kids at every holiday, I believed them—until I realized the…

CH2. My daughter swallowed something and needed an endoscopy. The doctor was performing the procedure when he suddenly stopped. “This is impossible. What I’m seeing inside her…” he showed me the screen. I gasped. My wife’s hand started shaking. The doctor called security

My daughter swallowed something and needed an endoscopy. The doctor was performing the procedure when he suddenly stopped. “This is…

CH2. My Sister Prank-Called My Boss And Got Me Fired. When I Got A Better Job, My Entire Family Demanded Handouts. I Smiled And Said, “Check Your Mailboxes!” Their Faces Turned Pale When They Opened…

My Sister Prank-Called My Boss And Got Me Fired. When I Got A Better Job, My Entire Family Demanded Handouts….

End of content

No more pages to load