My Son Got Hit by a Bike — My Parents Refused to Call an Ambulance: “Let Him Die, He’s Ruining Our Life.”

What happened next ended their control—and built us a life they can never touch.

Part I — The Sound You Don’t Forget

The scream had a high, tearing quality—like fabric ripping in a quiet room—and then everything went too still. It was a Saturday that smelled like rain and hot asphalt. My six-year-old, Noah, had his little red ball. My mother had her phone.

“Careful,” I called, wiping pine pollen from her porch rail because she’d told me to “clean the porch” and that translated to do as much as possible while I stare at a screen.

He grinned back at me over his shoulder, the dimple like a secret he gave me and no one else.

The ball popped loose, rolled toward the end of the driveway, over the faint white of our town’s neglected crosswalk. Tires shrieked. A silver blur. Then the sound—metal meeting small bone—and a scream that swallowed itself.

My body moved before thought did. I skidded on wet grit, knees tearing through denim, palms burning. Noah’s little body lay at a terrible angle. A slick warmth spread under my hands when I touched his hair. His arm was wrong. Children’s arms aren’t supposed to bend like paper clips.

“Noah,” I said, because that’s all there was. Names and breath. “Baby, look at me. Look at me.”

He whimpered, the sound caught in his throat. One of his shoes had come off. That detail would stick with me for weeks because it felt so… solvable. Shoes you can fix. You can press a Velcro strap into a rectangle and declare victory. The rest—the blood, the ghostly gray of his lips—felt like math from a book written in a language I didn’t know anymore.

I looked up at the house.

“Mom!” I screamed. “Dad! Call an ambulance. He’s bleeding.”

My mother opened the door like she was bored with the weather. She squinted as if the sight of her grandson on the pavement was a television show she hadn’t decided to commit to yet.

“What happened now?” she asked, like I’d misplaced a receipt.

“Please,” I said, and heard the feral edge in my own voice. “A car. He’s hurt. Call 911.”

My father shuffled out, the neck of his T-shirt stained with a circle of rusted sweat, a beer in his hand though he always swore he “never drank before five.” He took one long look and snorted.

“Always drama with you,” he muttered.

“This isn’t drama,” I said, ripping my shirt hem and pressing it to Noah’s scalp. The fabric went hot, then heavy. “Please. He’s losing blood.”

My mother crossed her arms, hip jutting, thumb flicking through invisible content on her phone.

“He’s fine,” she said. “Kids fall all the time.”

“A car hit him,” I said. “Look—”

There were tire scuffs in a sick arc, the kind that told a story: too fast, late sightline, panic. The cyclist—no car, I would learn later—had looked over his shoulder, saw me running, and pedaled like fear itself had a noise. Hit-and-run on two wheels.

“Then take him yourself,” my mother said, flipping her wrist. “We’re not wasting money on an ambulance. You can’t even pay your own bills.”

“This isn’t about money. He could—” I stopped, because there is a word mothers try not to ever say, and because my father said it for me.

“Maybe that’s what needs to happen,” he said, lifting the beer like a toast. “That kid’s been ruining our lives since he showed up. Always crying. Always needing something. You can’t even hold a job because of him.”

I felt the words hit the same way the bike had hit bone: too fast, too blunt, leaving something ugly caved in.

“He’s your grandson,” I said.

“Barely,” he replied, and took another sip.

My mother—my mother—laughed. “If you cared that much,” she said, “maybe you should have chosen a better father. Now deal with it.”

Something inside me broke with the clean snap of a dry stick. Not panic. Not grief. Something colder. Something like a switch you hadn’t noticed until your fingers found it in the dark.

I gathered Noah into my arms. He cried out, a small, thin sound, but his head found my neck, the way it did when he slept. He smelled like shampoo and copper. I stood.

“Fine,” I said. “I’ll do it myself.”

“Don’t bring him back here if he dies,” my father called as I turned toward the street. “We don’t need cops on our property.”

Their laughter followed me to the curb—bright, sharp, ridiculous against the gray of the sky—as if sound itself could be cruel.

I ran.

The rain came harder, needling my face. People stared. One man put his hand to his mouth. A woman stepped aside, pressed her palm to her heart. I barreled into the corner pharmacy and yelled, “Call 911!” The cashier went white and picked up the phone so fast the cord whipped.

Paramedics arrived in under three minutes. They moved like painters, like priests, like people who make decisions in the space between breaths. “You did good, Mom,” one of them said, and the words nearly undid me.

At the hospital, a young doctor with hair the color of burned toast said the words that would nest in my chest forever:

“If you hadn’t acted as fast as you did, he wouldn’t have made it.”

There are versions of yourself you meet only in rooms like that. I met the one who didn’t scream, who didn’t argue. The one who sat beside a small bed under a soft mammal of a machine and made a promise to an old window and the square of light it held:

They will never get to touch this life again.

Part II — The Math of Mercy

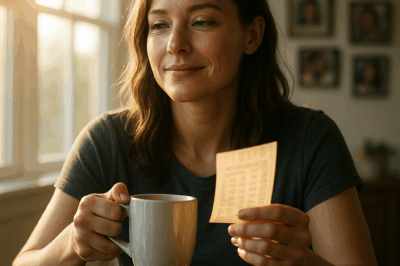

Three days later, the phone rang as if time had politely waited.

“You really embarrassed us,” my mother said. “Running down the street screaming like some lunatic with that kid in your arms. The Johnsons said you looked crazy.”

I was sitting beside Noah’s bed. His little head was wrapped in gauze, his arm in a sling that made him look like a very small, very fierce protestor after a rally. He had propped his toy car—the one he insisted on keeping with him—on his stomach and was teaching it how to whisper.

“Mom,” I said, and the word felt like something loose in my mouth. “He has a skull fracture. The surgeon said—”

“Oh, stop exaggerating.” She tsked. “You always twist things to make yourself the victim. That’s why nobody takes you seriously.”

My father’s voice was a background hum, an engine left idling in the driveway. “If you’d watched your brat instead of gossiping,” he said, “none of this would’ve happened. Don’t call again until you learn some respect.”

The line clicked. My hand shook around the plastic. Noah’s toy car whispered against cotton. The monitor ticked. I put the phone down like it had weight.

Noah blinked at me with those storm-cloud eyes.

“Mom?”

“I’m here,” I told him. “I’m not going anywhere.”

He nodded solemnly, like we’d signed something.

Something happened inside me then—not a decision so much as a spinal realignment. I’d spent years trying to pay my way into a family, tallying receipts like they could add up to love. I’d called that calculus “mercy.” But mercy that ends in blood on wet pavement is not mercy. It’s a math problem with the wrong variables.

So I started a different ledger.

I asked the pharmacy clerk for the footage from their security camera showing me running in with Noah. She handed it over like an absolution. I took photos of the skid marks and the smear where the bike tire had kissed rain and dirt. I saved the paramedics’ names. I wrote down times. I filed a police report for a hit-and-run, and when the officer raised his eyebrows at “hit-and-run” without a car, I quoted the statute from my phone and watched respect replace doubt.

A social worker came as required by law for pediatric trauma cases. She wore a cardigan the color of peaches and listened with the kind of attention that is its own medicine. I told her everything. Not with hysteria. With math. Times. Quotes. Witnesses. The sentence my father had thrown like a bottle. Let him die. He’s ruining our life.

She left with a look I’d never seen from a stranger: rage on my behalf.

I blocked my parents’ numbers and filed for an order of protection after my mother showed up at the hospital and tried to force security to let her in by saying I was “unfit and hysterical.” The judge looked at the photos and the notes and signed his name in a line that felt like a wall rising from the ground.

I found us a tiny apartment three blocks from the hospital—an old place with floors that complained and a view of the back of a bakery. Noah said the smell of bread was what heaven would be like if God had time to cook.

I picked up extra shifts at the diner nights I wasn’t in the hospital, a place where the coffee tasted like second chances and the dishwasher sang under his breath. I saved every receipt. Sometimes I stood in the alley behind the diner and looked up at the flare of flour dust escaping the bakery vent and told the night air my plan:

You are going to learn what asking looks like when help doesn’t come.

Not revenge. That word was too black, too simple. A correction. A recalibration.

Mercy, but correctly edged.

Part III — The Knock That Came Too Late

Two weeks after I brought Noah home—with his stitches like a tiny railroad across his hairline and his brave new arm sling decorated with two dozen stickers of cats on skateboards—there was a knock at my apartment door.

The landlord had warned me: “An older couple’s been sniffin’ around,” he’d said, scratching at a patch of paint that looked like the state of Ohio. “Said they were your folks. I told ’em I don’t disclose tenants.”

I opened the door with the chain still on.

My mother stood there without her pearls—without even the lacquer of superiority that she used like cosmetics. My father had ironed the crisp out of his shirt, like an apology he didn’t know how to offer. They looked smaller, the way people do when they’re standing on ground they don’t own.

“Clare,” my mother said. My name sounded like something you’d try to extract from a soft fruit.

“What do you want?” I asked.

She held an envelope like it had real mass. “We… we need your help.”

I thought of the hospital hallway, the scream, the way rain had beaded on the paramedic’s eyelashes. I thought of my son’s voice saying Mom? into a room that smelled like saline and lemon-scented floor cleaner.

“What did you need when I begged for help?” I asked. It wasn’t a rhetorical question. It landed between us with its own small sound.

“We were scared,” my mother said, and there it was—the old story polished for a new audience. “Your father’s blood pressure—”

“You laughed,” I said. “You told me to take him myself.” I lowered my voice because there is a power in small sounds. “You said, Let him die.”

Her face changed then—not the usual mask-slip, more like a sheet moved and the stain beneath revealed.

“We lost the house,” she blurted. “Your father… made some mistakes with money. We need—just until we get back on our feet.”

My father swallowed. I looked at the way his throat moved. I wondered if it felt like all the words were sharp now.

“You taught me,” I said quietly, “that help is for people you can use.” I tilted my head. “I’m unusable now.”

She looked so stunned I felt a flash of old daughter instinct, the one that wants to soften the world for people who only ever handed you knives. I didn’t open the door. Instead, I set my palm against it from the inside—a gesture as old as houses.

“Please,” my father said, the word awkward in his mouth, out of practice. “We could lose… everything.”

I pictured rain on the road and did the ugliest calculus I’ve ever done. What does a human being owe to people who told her the life she made was worthless? What does a mother owe to the people who tried to barter her son’s breath against their convenience?

“This is everything,” I said, and glanced over my shoulder at the little table with a single birthday balloon still deflating gently, at the crayon drawing Noah had taped to the wall of a big person holding a little person’s hand, both of them taller than the bakery. “And it’s not for sale.”

I closed the door.

They stood there a while. I could hear the scuff of their shoes. I leaned my forehead against the wood and shook until the door took some of it from me.

In the bedroom, Noah whispered to his toy car that Grandma and Grandpa’s voices sounded thin.

“They do,” I said, tucking the blanket under his chin. “Sometimes people get small.”

“Will we?”

“No.”

“Why?”

“Because we choose different.”

He nodded, solemn. “Good.”

Part IV — The Wall Holds, the World Witnesses

I didn’t tell anyone what I was doing. I didn’t post about it. The heart doesn’t need applause to stay alive.

But the world has a way of finding out what true things look like.

The pharmacy clerk told her cousin who told the hairdresser who told the woman whose mother is on the town council with a social worker who had a cardigan the color of peaches. Someone started a helmet drive in the park across from the bakery. A woman I didn’t know left a bag of groceries on my stoop with a note that said, Your bill at the diner is covered this week. –H.

The police found the cyclist. His back rim was bent and he’d Googled “how long do they check cameras after accident” like guilt could be outrun. I didn’t ask for prison. I asked for a check with a number the hospital would accept and community service fixing the crossings on our street while wearing a bright vest that said I DIDN’T STOP LAST TIME.

The DA liked my suggestion so much he sent an email with a subject line that made me cry: Alternative Sentencing Approved. I printed it and put it with the receipts and the police report and the photo of Noah’s stitches, a holy text I could pull out when the memory tried to lie to me.

A month later, my parents’ church called. The pastor—soft-spoken, trying and failing to sound neutral—asked if I would be willing to meet with them for “restoration.” I told him restoration is a carpentry term, not a liturgy. He tried again. I told him he could bring them bread from the bakery and tell them I said it wasn’t poisoned.

He laughed, then choked on it, shame catching in his throat.

The order of protection held. They tried my door once more, late on a Tuesday, my father’s knuckles dull on wood. I called the police without opening it. The officer—unremarkable uniform, remarkable gentleness—stood in the hall while my parents performed their duet, outrage-as-aria.

“She’s our daughter,” my mother said.

“And my son is my son,” I said. “So is my quiet. So is my door.”

The officer nodded. He had a daughter’s name tattooed on the inside of his wrist, small and blue. He looked at my mother like he’d made a list of what not to become and checked it twice.

They left.

The land behind them didn’t catch fire. The sky didn’t collapse. The bakery vent coughed flour into the air and the dog barked at a pigeon like he had important work.

Noah slept through it. He’d begun to ride a little blue bike we’d found on the curb, his arm strong again, his legs nervous and then sure. The first time he fell, he looked up at me with an expression I recognized from the mirror: shock, pain, calculation.

“What do we do?” he asked.

“We get up,” I said, and showed him how to check for blood, how to breathe through stinging palms, how to look left and right like it meant something. Then I made us hot chocolate. That’s the thing about mercy. When you do it right, it tastes like cocoa.

Part V — The Letter with No Return Address

Spring came in small, stubborn ways. Crocuses as rude as confetti. A sunbeam column in the diner on Tuesdays. Noah’s laugh getting bigger, his night terrors shrinking.

I got a job at the hospital cafeteria nights I wasn’t at the diner. The supervisor—surgical tattoos peeking from under her scrubs—said she’d put my application at the top because “your police report had the neatest handwriting I’ve ever seen,” and then looked slightly horrified that she’d said it out loud. We both laughed until we had to bend over.

There is a fellowship among women who have learned the world the hard way. We lend each other pens. We share snacks. We say me too quietly, as if we’re telling secrets to the moon.

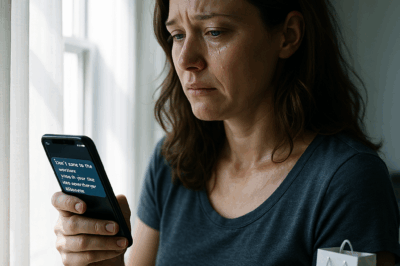

A letter came in April with my mother’s handwriting gripping the envelope too hard. No return address. Inside, one sentence on stationary that had once held Christmas newsletter bragging about Emma’s choir solos:

We finally understand what mercy costs.

I sat at the kitchen table and stared at it until the dog whined. I put it in the drawer with the receipts, not out of forgiveness, but because closure deserves a folder.

Noah is seven now. He told his therapist that “the bad car lives in my brain sometimes, but it’s smaller.” He showed her his scar and said, “This is how you can see I win.”

We bake cookies for the paramedics every December. One of them cried the first year and said, “No one ever remembers us after the crisis.” I told him I can’t afford to forget. We walked the skid marks last week and they are almost gone now, vanished under rain and time and the slow grace of tires that stop when they’re supposed to.

My father called once from a number I didn’t recognize because old habits die quieter than you’d think.

“I saw him,” he said without introducing himself, as if I wouldn’t recognize the shape of his voice. “On the bike. He looks good.”

“He is good,” I said.

He cleared his throat. “I—” He didn’t finish. He hung up. I let the silence stand.

Maybe one day there will be more letters. Maybe there won’t. Maybe apology is a language they will never be fluent in, and maybe that is not my job to teach.

Here’s what I know:

There is a difference between vengeance and a corrected equation. Mercy is not martyrdom. Boundaries are not cruelty. And love, real love, calls an ambulance and holds a small hand and sits in ugly fluorescent light without looking away.

My parents wanted me to learn what it felt like to beg and be met with silence. I did. At six years old, in my own parents’ driveway, with my son’s blood on my hands.

So when they begged, I met them with a silence of my own.

Not to be cruel. To be correct.

To build a life where my son’s name is never a punchline. Where help comes when it’s called. Where the only echo in our house is laughter that belongs to us.

Noah asked me last week if he can ride to the bakery by himself when he turns ten.

“Maybe,” I said. “We’ll see. We’ll practice. We’ll make sure the crossing is safe.”

He nodded, serious. “And if it’s not?”

“Then we wait,” I said. “Because that’s love too.”

He considered this, then held out his hand like he was swearing. I took it. We shook on a promise that cost nothing and meant everything.

Later, after he fell asleep with a book on his chest and the dog snoring in a way that made his lips flutter, I made a cup of tea and stood by the window. The bakery vent exhaled. The night took a deep breath with me.

I thought about the yard where it happened, the laughter that followed me to the street, the voice that said let him die.

Then I looked at my son’s small bicycle helmet hanging on its hook by the door, scuffed and bright, and I thought:

No.

Let him live.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. A cold, powerful CEO thought she could intimidate anyone with her sharp words — until she crossed paths with a single dad who refused to bow. When she snapped, “Peek once more and you’re fired!”, his calm, unexpected reply didn’t just shock her… it changed both their lives forever.

A cold, powerful CEO thought she could intimidate anyone with her sharp words — until she crossed paths with a…

CH2. In the middle of our wedding, my husband suddenly slapped me in front of everyone after his sister whispered something to him for a moment all the guests froze in shock. But instead of crying or running away. I looked him straight in the eyes, lifted my head high what I did in front of the guest ruined him…

In the middle of our wedding, my husband suddenly slapped me in front of everyone after his sister whispered something…

CH2. I Hid It From My Family When I Won The Lottery And It Was The Best Thing I Ever Did.

What Would You Do if You Suddenly Won $8.7 Million—but Knew Your Family Would Only See You as an ATM?…

CH2. At a party with my husband’s friends, I tried to kiss him while dancing. He pulled away and said, “I’d rather kiss my dog than kiss you.”

At a party with my husband’s friends, I tried to kiss him while dancing. He pulled away and said, “I’d…

CH2. “Don’t Come To The Wedding,” My Mom Texted. “You And Your Kids Just Make Things Awkward”. What happens next turns their picture-perfect family into complete chaos.

“Don’t Come To The Wedding,” My Mom Texted. “You And Your Kids Just Make Things Awkward.” What happened next turned…

CH2. I went to my mountain lodge to refresh, and found my sister, her hubby, and his family living there.

My Mountain Lodge Was Supposed to Be Quiet. Instead, I Found My Sister’s Christmas Party—In My House. Part I —…

End of content

No more pages to load