My parents treated me like a maid, until at my grandfather’s funeral…

Part I — The Smallest Room

My mother used to say that some people are born “helpful.”

What she meant was usable.

By the time I was nine, I could fold fitted sheets so tight they looked machine-wrapped. By twelve, I could iron a dress shirt without scorching the collar and arrange a cheese tray worthy of the glossy magazines on our coffee table. By fifteen, I knew which cabinet housed the good china and which housed the plates meant for people like me.

I am Sierra—thirty-four, Portland-born, and until recently, the Preston family’s most efficient appliance.

People like to pretend that cruelty arrives with a slam, a scream, a bruise. In our house, it arrived as a request with a smile.

“Sierra, be a dear and make your brothers’ lunches—your hands are so good with sandwiches.”

“Sierra, would you mind polishing the silver? James’s friends are coming and we want the house to look nice.”

“Sierra, don’t take it personally that we forgot your birthday. We were at Matthew’s playoff game—priorities, sweetheart. Family first.”

I learned early that “family” meant the three people in the glossy frames: my mother Patricia, my father Richard, my brothers James and Matthew. I was an addendum with chores. I slept in a windowless room at the end of the hall my mother called “the cozy nook”—another word for cupboard. It smelled like bleach and dust and the lemon oil I used to keep the baseboards shining.

Only one person made me feel visible: my grandfather Walter. He’d arrive every few months smelling faintly of pipe tobacco and rain, his hands big and careful around my small shoulders.

“You’ve got fire in you, kid,” he’d say, sneaking a paperback mystery into my apron pocket. “Don’t let them douse it just because they’re afraid of warmth.”

He taught me chess at the dining table on nights my parents went out—the only time my mother allowed the board out of its polished case. He’d wink when she scolded me for my hair, my grades, my voice.

“Kings fall if they forget the pawns move too,” he’d whisper as a bishop slid across oak.

I left the day after my twenty-first birthday, while the house was at one of James’s football games, the whole neighborhood unfurling banners for his scholarship. I took two bags—the clothes I’d bought with my hotel pay and a shoebox of paperbacks Grandpa had slipped me over the years. I didn’t make a speech, didn’t allow anyone the theater of an argument. I simply stepped out into a drizzle that felt like applause.

It took me thirteen years to build a life. There were cheap rooms and two jobs and classes that began when the city yawned itself to sleep. There was a bakery in Southeast that started as a sliver of a storefront and grew until strangers learned my name by the taste of my cardamom braid. There were holidays with chosen family—friends who didn’t measure love in chores completed.

I saw my mother once, five years ago, at a store in the Pearl District that sold organic milk like perfume.

“Still cleaning up after people?” she said, eyes traveling from my shoes to my hands.

“Yes,” I said. “But for a living now.”

I returned to work smelling like cinnamon and felt no need to cry in the walk-in.

Then the call came. The number was unfamiliar, the voice was careful. “Ms. Preston—sorry, is it Ms. Preston or Ms.—” the woman corrected herself. “Sierra. My name is Amelia. I’m calling from Gulliver & Ames. I’m very sorry to say Walter Preston passed away this week. The funeral is Saturday.”

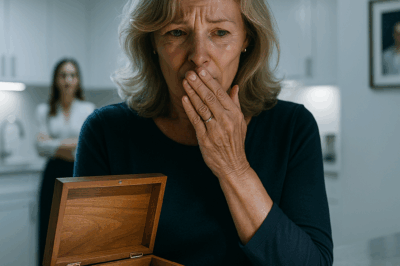

I stood behind the bakery counter with flour on my palms and felt the world reach under my ribs and twist. The one person who’d looked me in the eye and seen a person, gone.

“Will the family—it’s private?” I asked, already hearing my mother’s voice saying yes, private, always private.

“All are welcome,” Amelia said. “Mr. Preston insisted.”

So I went. Not for them. For the man who taught me that there are fifty-four ways to lose a chess game and fifty-five to win.

I wore the only black dress I owned, the one I’d bought with the bakery’s first big catering payment. The funeral home smelled like lilies and lemon cleaner. The Preston family glided through murmurs like swans—white, graceful, expensive. My mother dabbed at a perfectly dry eye with a monogrammed handkerchief. My father’s hand stayed on her elbow like a handle. My brothers shook hands, accepted condolences, told the same story three times about Grandpa’s love of fly fishing.

I stood at the back with a lily and a throat that felt like sand.

I was lining up an exit when an elderly woman with white hair pinned flawlessly at the nape of her neck touched my sleeve. Her eyes were a pale, troubling blue.

“Sierra?” she whispered.

“It’s just Sierra,” I said, the old habit flaring—the refusal to wear their name anymore.

She looked past me, and when no one was watching, pressed a yellowed envelope into my hand. “I worked at Sunshine Services in 1994,” she said, the words quick, guilty. “I’ve waited thirty years to tell you. I’m sorry. I’m so sorry.”

“For what?” I asked, though something in me had already braced, as if preparing for a wave too large to outrun.

“You weren’t adopted,” she said. “You were stolen.”

The lily fell to the carpet at our feet. Somewhere near the front, my mother laughed at something a neighbor said about casseroles.

The woman’s name was Edith Mercer. Her hands shook as she explained in whispers: forged papers, cash in manila envelopes, a boy vanished from a backyard in Seattle, a ransom that went wrong, a story that made national news. A clipping slid from the envelope into my palm. A little blonde girl, four at most, on a man’s lap, a woman leaning in from the side. All three of them smiling like people who don’t know what grief tastes like yet.

MISSING: SIERRA WILSON, APRIL 1994.

“She’s—” I started. The sentence died in my mouth.

“You,” Edith whispered. “Your parents never stopped looking. They would have found you sooner, but your… the Prestons had friends in offices where consent can be stamped.”

“Why now?” I asked. “Why tell me here?”

“Because I am dying,” she said simply. “And because Walter told me once—he came to the office, you know. Forty pounds lighter, eyes like knives. He told me, ‘If you ever find a spine behind your sins, you will tell her. Don’t let my death be another lie in that house.’”

I looked toward the front where my mother now held court over a tray of lemon bars she didn’t bake.

I slipped the envelope into my bag and left without saying goodbye.

Part II — The DNA and the Will

Grief is a fog. Identity crisis is lightning.

By Monday morning, an investigator named Daniel sat at my small kitchen table above the bakery, pulling a sterile swab from a paper sleeve. He was gentle the way men learn to be when the truth could slice either direction. A week later, he returned with a printout that changed everything and nothing.

99.9% match. Sierra Wilson of Seattle, daughter of Benjamin and Clare Wilson. Lost April 1994. Found thirty years later in a city two hundred miles and a universe away.

I shook, then ate a piece of toast because the body gets hungry even when the soul is confused. Daniel watched the toaster pop and said, “They never stopped. You should know that. Your parents—they never stopped.”

“Walter stopped them,” I said, and it came out not as an accusation but as a gratitude. He had held the door to community closed because he’d seen what that community had done to me. He had left the bolt on and slipped me books through the mail slot.

“Maybe,” Daniel said. “But maybe he was also paying a debt the only way he knew how.”

The next call was from an attorney—Amelia again, her voice softer. “Miss—Sierra. Mr. Preston left a will. There’s a codicil of special instruction. Would you be willing to come in before the family gathering?”

I almost said no. Then I imagined Walter across a chess board sliding a pawn and raising an eyebrow. Your move, kiddo.

The law office was downtown and smells like old wood and good paper. The conference room overlooked the river. My mother’s laugh was in that room, of course—she wore it like armor. My father’s jaw was clenched at a familiar angle. My brothers sprawled in suits that fit like apologies.

I was invited in last.

Amelia cleared her throat. “Mr. Preston’s will divides most of his estate between his children and grandchildren. However, there is an attached letter and a separate bequest with specific instructions. He asked that we read it aloud.”

She unfolded a page written in Walter’s impatient hand.

“If this is read, it means I am at last where your mother has been waiting for me, and I hope she’s laughing still. Richard, Patricia, if you are in this room, it means I failed you. If Sierra is not in this room, it means you failed me. Sierra, if you are here, I hope they didn’t make you sit at the back.”

“I counted how many times a pair of small hands set a table for me when mine were arthritic. I counted how many times those hands cooked meals and wore a smile like a uniform. You taught me a lot about courage, kid.”

“On March 19, 2011, I created a trust. It vests fully if, on the day of my funeral, Sierra stands farther from the family pews than the nieces and nephews who were taught to love my money more than my jokes. If Sierra is in this room and the first to be asked to fetch, the trust vests immediately with penalties applied to anyone covering inheritance with contempt.”

“The trust includes: the house in Sellwood, the cabin in Manzanita, the bakery building on 12th. Yes, Sierra, it’s been yours for three years; I just wanted to see you sign a lease with confidence. The trust includes the cash I lied about not having, because if I told your mother, she’d have spent it on lemon bars and Lexus maintenance.”

“The final instruction: the truth. I leave a sealed packet with Amelia. If Sierra wants it read, it’ll be read. If she doesn’t, she can burn it and take me fishing in her head and call it even.”

My mother’s face did not move. My father’s mouth opened, closed, opened again. James blinked. Matthew swore under his breath.

“Furthermore,” Amelia said, clearing sunlight from her voice, “Mr. Preston’s codicil contains a clause: any beneficiary who challenges Sierra’s bequest forfeits their portion. He called it”—she glanced down with a small smile—“‘the rudeness tax.’”

“Ridiculous,” my mother said, but softer than usual.

“I’d like the packet,” I said, surprised by the steadiness in my voice.

Amelia passed me a thick envelope. I slid my thumbnail under the flap. News clippings slid to the table like fallen birds. The same face looked up at me—the four-year-old with the blue plastic truck. The words screamed in headlines: MISSING. HOPE FADING. REWARD DOUBLED.

Behind them was something else: a photocopy of a receipt from Sunshine Services dated 1994. A signature I recognized as my father’s. Not Walter’s. Richard. A name that saw me as use and signed me anyway.

My stomach did a particular twist—the one it does when the roller coaster tips toward the drop. I looked up at him. “Why?”

“Your grandfather insisted,” my father said too quickly. “You know him. He controlled everything. We took you in to—”

“To what?” I asked. “To practice generosity? You put me in a closet and called it family.”

He flinched.

“Enough,” my mother said, reaching for her handkerchief like a sword. “We did our best. Walter always preferred her, even as a—” she stopped, forced the next word out like a pill. “—child.”

Amelia’s assistant appeared in the doorway, almost apologetic. “The Wilsons are here.”

The room thinned. My mother’s face blanched under good makeup. My father stood like a man preparing for weather he couldn’t afford.

Benjamin and Clare Wilson walked into that room holding hands like people who have learned the cost of empty palms. They wore grief like a suit that fits, not comfortably, but honestly. They looked first at me, then at the space between all of us, measuring.

“Hello,” Benjamin said, voice low enough that everyone had to stop pretending to be busy. “We’d like to meet our daughter, if she’s willing.”

“She is,” I said, the words landing on the tablecloth like a rook.

My mother stood. “This is a private family matter,” she said to the air.

“So it is,” Clare said, and her voice—God, her voice sounded like the lullabies I don’t remember—“and we are her family.”

No one told me what to do next. I didn’t need it. I crossed the room. We stood, the three of us, not speaking. Then Clare lifted a hand slowly, permission in her palm. I nodded. Her arms were warm. Benjamin’s were steady. If this were a movie, there would be swelling strings; in real life there was the sound of Portland rain and my mother’s breath catching like a heel on a cracked sidewalk.

Amelia’s voice cut through the moment gently. “Given the circumstances and Mr. Preston’s clauses, I suggest we adjourn. There will be time to sort accounts. There is not infinite time to repair lives.”

My mother didn’t look at me when they left. My father did—once, and then away, like the sun over water.

Grandpa’s chess set was waiting when I went home. The pieces smelled faintly of cedar and his aftershave. I set them up because the body remembers how to move even when the soul is out of practice. The black knight leaned a little. I let it.

Part III — The House That Wasn’t a Prison

There are reunions that are fireworks, and there are reunions that are tea. Mine was tea.

Benjamin and Clare sat at my bakery’s tiny back table on a Tuesday, drinking chamomile and talking like people who had grief as a second language. They didn’t ask questions like lawyers; they asked them like gardeners—slowly, gently, understanding that some answers need weather to grow.

“Do you sleep?” Clare asked, and I almost laughed because everyone else had asked what now or how do you feel like feelings were a menu I could order from.

“Sometimes,” I said. “I used to fall asleep eating toast because I didn’t want to waste daylight. Now the house is—” I paused. “It’s mine. That’s new.”

“Will you… let us in?” Benjamin asked, and there it was—the decency. The refusal to barge. He could have bought half the block with guilt money; instead, he offered me a doorbell.

“We could start with breakfast,” I said. “I make a mean frittata.”

We did. Over herb frittata and burnt edges and too much pepper, I learned things I didn’t know I needed to know. About a woman who danced badly in the kitchen and laughed when the dog jumped. About a man who built treehouses without instructions and bruised his shins and didn’t swear in front of small ears. About a little girl who collected rocks and said they were planets. About the Wilsons spending not just money but years, billboards, and breaths searching for a ghost.

When we finished, Benjamin pulled a folded check from his pocket and slid it across the table without flair. “The reward—Walter matched twice,” he said. “It paid for tips that turned out to be scams, but it kept people walking with our photo. It is yours. It was always meant to be yours, find you or not. Please don’t argue.”

“I wouldn’t,” I said, and we all laughed the brittle laugh of people who know dignity sometimes requires letting others be generous.

Walter’s trust took care of the rest: the bakery building (which I had been renting from a faceless LLC that turned out to be his wink), the cabin in Manzanita (which smelled like his wool caps and damp wood), a small house in Sellwood with a garden that had been pitying the weeds. The papers were tidy; the heart was not.

“What do you want to do with the Preston house?” Amelia asked over the phone later that week, and I felt my stomach do the old twist.

“Sell it,” I said, and then, because chess teaches mercy in endgames, “Unless Patricia can afford to buy it legally at market rate.”

“She cannot,” Amelia said, and both our voices did that small cruel thing where relief is not noble.

We sold it fast. The staged photos online made me laugh—my mother’s lemons and light and a written promise that the “cozy third bedroom” got great afternoon sun. I slept for three nights after the sale closed—deep, heavy, dreamless sleep.

The hearing that sealed everything was not a trial—those would come later for other people. This was paperwork with rules. Richard’s signature was a forest of half-apologies; Patricia’s was neat and furious. When the judge asked if anyone wanted to contest the trust, my mother opened her mouth. James touched her arm. For once, she closed it.

Outside, the press created a new universe I did not want to live in. People asked for statements. I went to work. I rolled dough. I iced cookies. I started a fund for missing children that did not require a parent to promise their soul for help.

Sometimes neighborhood ladies came in and whispered that they had known all along something was wrong in that house. I smiled at them the way you smile at weather. Sometimes a man would say “I played rugby with James” and I would hand him a cinnamon roll and say “he favored his left side; teach your sons not to.”

One afternoon, Edith Mercer walked into the bakery with her small, careful steps. Her hair was now a soft halo of white. The room went quiet—the way rooms do when ghosts show up and order coffee.

“I didn’t know if you’d want to see me,” she said.

“I would have come to you,” I answered, and meant it.

She cried as she ate the carrot cake. Not because of the cake (though she complimented the spice level) but because she had finally told the truth to the face she’d feared. I poured her more tea and said, “You ruined something. You also saved something. Both can be true.”

“I don’t deserve your bakery,” she whispered.

“No one deserves a bakery,” I smiled. “We just get to walk in and be fed or we don’t. Today you do.”

The Wilsons came every Sunday then. Sometimes we closed early and ate at the long table in back. We argued about crossword clues and the best way to stack scones and whether you can put sugar on tomato slices without becoming a monster. We played chess until the dog knocked the pieces with his tail and looked proud.

I visited Manzanita alone for the first time in June. The cabin door stuck because it had been painted too many times. Inside, the rooms smelled like cedar and salt and the ghost of pipe smoke I had always pretended to hate and truly loved. I took Walter’s old rod to the shore, didn’t fish, sat on the log and spoke out loud to the idiot gulls.

“Your rudeness tax worked,” I told the wind. “You old fraud.”

A gull screamed like it agreed.

Part IV — Checkmate, with Mercy

The last time I saw my mother was in a courtroom hallway where the floors made everyone fancy whether they deserved it or not.

She stood with her lawyer in navy and a string of pearls that looked like she’d bought them to go with a script. Her hair was still perfect. Her hands were empty.

“Sierra,” she said, and there it was—the crackle in my chest where a daughter lives even when she tries to move to a new address.

“Patricia,” I said back because names are grants of power.

“I didn’t know,” she began. “Your father said—” she swallowed. “He said Walter wanted it that way. That we were… helping.”

“You told people I was lucky you took me in,” I said, and my voice did not wobble. “You told neighbors I should be grateful to scrub your floors. You told a judge today that the trust was unfair because I hadn’t earned it.”

Her face pinched. “We fed you.”

“You fed me when it benefited you,” I said, and placed my hands flat against the cool marble so I wouldn’t make a fist out of old habit. “You didn’t feed me because my body mattered to you. The bakery feeds people because their bodies matter to me. That is the difference.”

Tears gathered, wrecking a mascara job that believed in itself. “I’m your mother,” she said, and somehow made it sound like a threat.

“You were a woman in a house where I lived,” I answered gently. “Mothers are more than biology and a history of nice Christmas cards. I hope you find peace. I hope you stop performing empathy and try it on in private. I hope you cut lemons for yourself in a kitchen you can afford.”

“I didn’t kill you,” she blurted, and it was so absurd we both laughed.

“No,” I said. “Walter kept you from finishing me. I did the rest.”

“Do you need anything?” she asked, and meant money because that was her only language.

“I need you to learn a different one,” I said, and walked away.

Outside the building, the sky had the indecent good manners of a blue Oregon day. I squinted at it and then at the life that waited.

A little girl dragged her mother into the bakery by the hand and pressed her nose to the glass to stare at the lemon tarts like they were strangers that might be friends if they were kind. The dog lay on the welcome mat, invented a new way to nap, and sighed a sigh that could make saints bend.

Benjamin and Clare came down the block carrying a basket of jars—pickles they’d made as a hobby during a pandemic none of us wanted to talk about ever again. Clare kissed my forehead like she’d been waiting thirty years to do that one small thing. Benjamin held the door while a couple in hiking boots attempted to juggle coffee and croissants and gratitude.

“Tell me something ordinary,” I said to him because you must ask for small stories as often as the big ones.

“The basil survived the slugs,” he said solemnly, and we both cheered.

That afternoon, I closed early. The sign on the door said Back at 4. Building an Endgame. People smiled as they walked past because Portland likes a joke that doesn’t try too hard.

I set up the chessboard. The black knight still leaned; I still let it. The Wilsons took their usual seats, and the Preston ghosts sat in the space above my shoulder where the ache now lives quietly and does not interrupt the moves.

Clare poured tea. Benjamin slid a pawn—two squares out of habit, one to be clever. I moved my queen out fast—not a move I’d used when I was a girl in a cupboard. You learn, when no one hands you clean openings, to make your own.

“Bold,” Benjamin said, smiling.

“Necessary,” I replied.

“Most good things are,” Clare added, and tapped her mug to mine like a toast to a language we all now spoke fluently.

As the afternoon light cut the room into good angles, I rested my hand over a piece, felt the weight of it, and recognized the sensation at last: not fear, not grief, not hunger.

Choice.

I made my move.

And somewhere, if ghosts can be smug, Walter laughed and said what he’d always said after a game well played:

“Checkmate, kiddo. Now—eat.”

I did.

And for once, no one asked me to wash the dishes before I was done.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. At Dinner, She Smirked: “My Ex Just Texted – I’m Meeting Him For ‘Closure’ Tomorrow.” I Just Nodded: “That’s Thoughtful.” The Next Morning, Her Bags Were Professionally Packed, The Locks Changed, And A Moving Truck Waiting. When She Came Back From Her “Closure” Meeting… She Realized I’d Already Closed Everything…..

At Dinner, She Smirked: “My Ex Just Texted — I’m Meeting Him for ‘Closure’ Tomorrow.” I Just Nodded: “That’s Thoughtful.”…

CH2. Parents Told Me, “Skip Thanksgiving — We Need Space.” But Their Regret Came Quickly

Parents Told Me, “Skip Thanksgiving — We Need Space.” But Their Regret Came Quickly Part I — The Message The…

CH2. My Daughter Betrayed Me… But My Late Husband Saved Me

My Daughter Betrayed Me… But My Late Husband Saved Me My daughter thought she could take everything—my beach house, my…

CH2. My Family Skipped My Child’s Surgery, Then Demanded $5,000 — and Called the Bank When I Laughed…

My Family Skipped My Child’s Surgery, Then Demanded $5,000 — and Called the Bank When I Laughed… Part I —…

CH2. The Family Of My Daughter-In-Law Pushed My Grandson Into The Lake… But They Didn’t Know My Brother

The Family Of My Daughter-In-Law Pushed My Grandson Into The Lake… But They Didn’t Know My Brother Part I —…

CH2. After my mother chose my stepfather over me, I was forced to live on the streets at 16. “He’s not worth the trouble,” she said. I cleaned toilets for money. Monday, a detective found me: “Your real father in Germany spent millions searching for you. He left his automobile empire worth $2.1 billion -to claim it, you have 72 hours to your family’s darkest secret”

After my mother chose my stepfather over me, I was forced to live on the streets at 16. “He’s not…

End of content

No more pages to load