When architect and single mom Clara Morgan built the carriage house behind her parents’ home, she thought she was rebuilding her life — not signing a lease on heartbreak. Years of quiet effort, repairs, and rent receipts meant nothing when her sister decided it was the “perfect starter home.” Her parents agreed. And when Clara refused to hand it over, they hired a lawyer — and served their own daughter. But in court, it wasn’t Clara who spoke. It was her seven-year-old daughter, holding a tablet with a secret that would expose everything her family tried to hide.

Part 1 — Foundations

My parents sued to evict me so my sister could own her first home. There it is in one sentence, the kind journalists love because it fits under a headline and still feels unbelievable. What doesn’t fit in a sentence is how a person ends up at a table with their name spelled right on a summons and wrong in the mouths of people who raised them.

My name is Clara Morgan. I’m thirty-five. Architect by training, single mother by the kind of decision that looks brave to outsiders and ordinary to anyone who has ever held a colicky baby at 3 a.m. and said, Okay, we’re doing this.

The carriage house sat forty-three measured paces behind my parents’ shingled colonial, across a lawn my father used to mow in perfect parallel lines like he was drafting blueprints with grass. The carriage house wasn’t romantic when I moved into it. It was a tired rectangle with a bowing ridge and old wiring that hummed like a bad memory. But it was mine to work with. The deal had been simple: they would lease me the land for a nominal fee; I would fund and manage the rehab. “Temporary,” my father said when we signed the papers at their kitchen table. “We’ll see where you land, honey,” my mother added, smoothing the edge of the contract as if it were a bedsheet.

Temporary is a word that makes time behave for the person who says it. For the person who hears it, it’s a countdown you can’t see.

I planned, drew, and filed. I pulled permits and the sliding glass door out of a salvage yard for a scandalously good price. I hired a roofer for the pieces I couldn’t do. The rest I did myself. Framing when Norah was at school. Wiring at night after she slept, crouched under a headlamp, fishing cable through ribs of new walls like thread. I installed egress windows with an angle grinder and caution and the kind of prayer that is mostly measured math. When we moved in, the two of us carried boxes like they were history, and I set the last one down in the bedroom and cried from the stupid relief of putting things where they go.

Two years is a long time when you spend it making repairs and soups. It is not long enough for a family to learn a new habit.

It started at Sunday dinner the way most intrafamilial earthquakes do—under the tablecloth. My mother had polished the lemon oil into the dining table until it reflected our faces like the surface of a pond. Roast chicken, haricots verts that squeaked against teeth, a pie that looked better than it tasted. The old rituals were there, down to my father’s joke about dark meat being for people who didn’t understand the bird.

Ava swirled her Pinot like a person who had learned that gesture off a screen. “It’s kind of perfect back there,” she said, light as a caption. “Like a starter home.”

“For who?” I asked.

“For me,” she said. “I’m thirty. It’s time to own something.”

She didn’t look at me when she said it. She looked at my parents, because that’s where the power sat at that table. My mother smiled the smile she uses when she’s about to say no to a favor by making it sound like a yes to something else. My father pretended to saw the drumstick with more effort than required. Norah tugged my sleeve. “Can I have yours?” she whispered. “Take both,” I said because suddenly I didn’t want any of it.

The next week, my mother invited me for coffee “just us” and set a blue folder on the table between us like a centerpiece. “We’ve been talking,” she began, and something in my ribs braced. “Ava’s been saving. We think it’s time to make things official.”

“Official how?”

She slid the folder across the surface I’d buffed and sanded with my own hands when I was nineteen and heartbroken for the first time. Inside: a typed agreement with clean fonts and cold intentions. Ninety days’ notice to vacate. A revised lease naming Ava as the incoming tenant. A paragraph referencing “family legacy.”

I laughed. It came out wrong—a tired animal sound. “Legacy?” I said. “You mean the shed I turned into a home?”

“Don’t be dramatic,” my mother chided, the way she used to when I cried at seven because a teacher told me my T-square wasn’t straight. “This is what’s fair.”

“Fair,” I repeated, like tasting a word to see if it had gone bad. “Because I’m useful?”

“Because you’re resilient,” she said, and patted my hand like she was offering me a marriage.

When you realize the family meeting is an ambush, it rearranges the way your name sounds in their mouths. They said legacy. The summons that came by certified mail two weeks later said defendant.

I am not a lawyer by training. I am by necessity. I scanned the statute my parents’ attorney cited: permissive use, familial license, no tenancy created. I read it twice. Then I did what I know how to do: I documented. Every Venmo memo that read carriage house utilities. Every text from my mother—Thanks again for covering taxes!—that she had sent when my father misremembered a due date. Every receipt for wiring, insulation, the CO detectors I’d installed with Norah looking on like I was performing a magic trick. I printed emails and circled dates. I slid them into labeled folders that made the kitchen look like a case study in quiet rage. Norah called them “Mom’s homework.”

At night, after she slept, I sat by the window and watched the backyard lights blink on like a stage set. From this distance, my parents’ house looked like a watercolor of home. From up close, manipulation had fingerprints. Ava began dropping by “just to look,” and her eyes measured walls the way mine used to measure rooms I was paid to redesign. “Floating shelves here,” she mused. “Maybe paint the brick a warmer tone.” I learned how to occupy a doorway without moving.

Norah asked, “Are we moving?” and the truth split in my mouth. “Not if I can help it,” I said. She slid her hand into mine with the kind of confidence children have in the people they live inside of. “You can help it,” she said. My chest ached.

I called Ethan, my ex, whom I still liked better than I’d loved him. “They served me,” I said. “Certified mail and everything.”

He whistled. “What do you need?”

“Just be ready to take Norah if this…requires a room where she doesn’t belong,” I said.

“You got it,” he told me and didn’t say the thing everyone else loved to try—Are you sure you aren’t overreacting?—because he had watched my mother with me for a decade.

I practiced calm in the mirror because I know how quickly an upset woman gets called hysterical and how rarely a calm one gets punished for the same emotion. I bought a new blazer from a consignment store because armor reads better in wool than in pleas. I checked the CO detectors twice a week. If you have ever built a life out of borrowed time, you know that safety can be a ritual you perform while you wait for the trouble you can see coming.

Part 2 — The Door We Closed

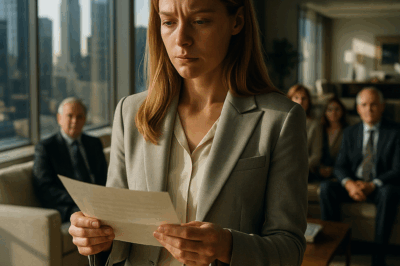

Courtrooms are smaller than the ones on television and quieter, like the silence has been sanded by years of repetition. The judge in our case wore her hair in a bun that looked practical and had a voice that made people hush themselves.

My parents sat at the petitioner’s table with Ava between them, their shoulders nearly touching as if proximity were strategy. My parents’ lawyer had a tie that cost what my first drill cost times eight and a voice that smiled.

“Your honor,” he said. “This property has always been permissive use—an act of familial generosity. Ms. Ava Morgan seeks only the opportunity to begin a life of her own. A first home.”

He said first home the way pastors say forever.

When it was my turn, I stood and felt two things at once: my knees relearning how to be legs and my voice deciding it was time to arrive. “I’m not a squatter,” I said, which should not be a sentence a person says to their parents in public. “I’m their daughter. I funded and executed a full rehabilitation with permission. I have paid utilities, taxes, and repairs, and I have documents to support all of it.”

Paper makes a sound when you put it down with intention. It sounds like a door closing correctly.

We walked through the exhibit list—screenshots of my mother’s texts, receipts, PDFs of permits with my signature, a photo of me covered in insulation dust holding Norah’s hand after we hung the last sheet of drywall. The judge asked clarifying questions. My parents’ lawyer tried to talk about “family spirit,” and the judge asked him for legal citations instead. He shuffled.

Ava asked to speak. She stood in a white blazer that would look innocent in a grocery store and adversarial under fluorescent lights. “I’m not the bad guy,” she said. “I’ve been saving. I deserve a safe home.” She looked at me as if I were the person who had invented rent.

“You do,” I said before the judge could. “You deserve a safe home. It just doesn’t have to be mine.”

My father muttered something like ungrateful under his breath and the judge snapped her eyes to him. “Enough,” she said, and how I loved that word in her mouth.

Then: a tug at my sleeve. Norah. “Mom,” she whispered. “Can I show the judge something you don’t know?”

Time did the thing it does when a child is about to change a room: it widened.

The judge looked at her, then at me. “May she?” she asked.

I nodded because my body had already decided yes before my brain had gotten there. Norah stepped up on the little wooden riser that children use in these rooms and produced her tablet like it was a trophy.

“It’s from our camera,” she said, voice small but laid on a foundation I recognized. “I saved it.”

She tapped play. The screen showed our living room in daylight. The timestamp sat in the top corner like a witness. The door opened. My mother entered first. Ava followed. My mother’s hand went to the stack of mail with the accuracy of habit and she riffled through like looking for her name. Ava crossed to the carbon monoxide detector and reached up. She twisted. The unit chirped. She popped the battery out the way you pop the back off your confidence.

“Don’t touch that,” my mother said, but her voice didn’t carry warning. It carried theater.

“If the inspection fails,” Ava replied, laugh something like a cough, “she’ll have to move. It’s faster.”

My mother didn’t stop her. She lifted my drawings from the console and glanced at them. “We’ll say we thought these were old,” she said the way people say grace by rote. And then—because heaven has a sense of timing—Norah’s tiny voice from the speaker, off camera: “Hi, Auntie.”

Ava turned to the lens with a face that had learned two expressions well. She put on the one for children. “Hey, sweetie,” she cooed. “Secret, okay? Don’t tell Mommy.”

The clip ended because Norah had moved to stand between Ava and the doorway with a force misspelled by most adults as innocence.

The silence after that kind of evidence feels like a structural inspection. The building holds or it doesn’t. The judge closed her eyes briefly and opened them on my mother. “Ma’am?” she asked, and the whole history of our family collapsed into that single syllable.

My mother’s mouth opened to shape a lie and remembered there were still cameras in the world. “We didn’t mean—” she began.

The judge raised a finger. “Here’s what we’re not going to do,” she said, and the courtroom leaned in. “We are not going to pretend this is empowerment when the record shows manipulation. We are not going to abuse the law to punish a daughter for her competence.”

She signed the order with ink that sounded like finality. “Petition denied with prejudice. A protective injunction is entered. Ms. Morgan”—she looked at me—“change your locks.”

I didn’t cry there. It would have diluted the clarity.

Part 3 — The Quiet Click

The morning after court, I changed the locks on the carriage house.

There is a very particular sound a new deadbolt makes when it settles into a plate you measured twice. It is the sound a door makes when it knows it will not betray you. Click: not a slam. Not a barricade. A boundary speaking softly but out loud.

I hired an electrician I’d never met to re-run a section of wiring I had already done myself. “You sure?” he asked when he saw the neatness of the conduit I’d strapped to the studs two summers ago.

“Very,” I said. Part of what had gotten me here was my habit of sparing everyone else the bill. I watched him work and didn’t offer to hold the ladder even when he wobbled.

By noon, the carriage house felt different. Nothing that a camera would record. Something like the air after a storm that finally decides to leave the county. Norah came home from school and checked the CO detector like a pro, pressing the test button and waiting for the reassuring veeek and flashing light.

“Still working,” she said, and stared at me with pride so physical I could feel its weight on my shoulder.

“That’s the point,” I told her. “Not to be afraid. To know.”

My phone exploded that evening. Missed calls from my mother, my father, my mother again from the landline—the one in the kitchen that still has a spiral cord because some things those two will never update. Ava’s texts came without punctuation: we should talk why are you doing this you made us look awful

I typed and erased twice. I didn’t trust the tone in my hands. I wrote a letter instead. One page. No adjectives. The kind of letter you can file in a drawer and not need a glass of water after reading.

Mom, Dad, Ava—

I love you. That has not changed. What has changed is access. You do not have keys to my home. You do not decide where I live. You do not enter without my permission. This is not revenge. It is a boundary. If you would like a relationship with me and with Norah, it will be on the other side of therapy, not court. Here are three names.

—Clara

I printed it and dropped it in their mailbox because some things I will not deliver with an electronic chime.

Three days later, my father appeared on the sidewalk outside the carriage house with his arms crossed in a way that had intimidated me when I was thirteen and didn’t anymore. He stood there like a No Trespassing sign wished it had his eyebrows.

“You embarrassed us,” he said without hello.

“In a room you hired,” I answered.

“Your mother can’t sleep,” he said.

“She’s not ill,” I replied. “She’s disappointed she didn’t win.”

He shifted on his heels. “We were trying to help your sister,” he offered, which had always been the bedrock of his defense.

“I know,” I said. “You always are.”

“She’s the baby,” he said, a sentence I have heard in my bones since I was five and lost my red ribbon and the story became about keeping Ava’s clean.

“Buy her a crib,” I said, and watched the words land. “Stop asking me to be the mattress.”

He blinked and looked at the side of the carriage house like maybe the wood would bail him out. Then he went home. He is not a man who retreats often. I stood under the eaves and let the rain gutter ping out its last drips into the downspout and counted my breaths until I remembered where my hands were.

The quiet that followed was like new paint: too shiny at first, then somehow correct. No drop-ins. No casseroles. No piles of mail with my name thumbed through by someone else’s hands. Ava posted a photo of a condo key on Instagram with a caption about “homeowner vibes.” The comments were confetti. I didn’t flinch when I scrolled past it days later because peace is not a sport with a scoreboard. It is a porch light you turn on for yourself.

Norah and I built things. A loft bed with drawers in her steps because I am still that mother who gets cavities from her own child’s smile. A shelf in the kitchen shaped like a cloud because she said it would make the toaster brave. A cedar bird feeder that required us to learn how to listen for small weights. On Sunday mornings, she would test the CO detector and grin at the obedient beep like she was commanding a small dragon.

“The alarm still works,” she would say.

“Good,” I would answer.

A court order lives in a clear sleeve in my desk drawer. Not as a weapon. As an artifact. On days when guilt still finds ways to pick locks, I open the drawer, slide a fingertip along the edge of the paper, and remind myself I did not hallucinate the harm just because it was done in a kitchen and not a dark alley.

Part 4 — Aftercare

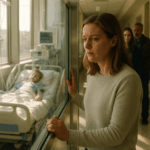

If this were a movie, my sister would have a tearful monologue in the rain. My parents would discover their capacity to love me without manipulating me in a scene at a hospital. Someone would finally say what they meant with the kind of clarity that fixes things.

Movies like that are comfort food. This is a recipe that took longer and needed fewer spices.

The first attempt at reconciliation came over text. My mother: We overreacted. Ava: Let’s talk. My father: Family is messy. Three true things used as apology’s costume. I replied with a list of therapy dates, first appointment paid, three counselors who specialize in family systems. If they showed up, I would too. If they didn’t, I wouldn’t drag a chair into a room alone so they could watch me sit.

Sometimes they went. Sometimes they didn’t. Sometimes the doorbell rang and I let it, and sometimes it rang and I didn’t. Boundaries are not punctual. They are stubborn.

One Saturday in late spring, I saw Ava at the grocery store, the two of us lugging milk and eggs and the kind of screws you tell yourself you don’t need until the hinge comes off the cupboard door.

“Hey,” she said, voice bright. She had put on the version of herself that belonged in a light aisle—cheerful, a little reflective. “We should talk.”

“We are,” I said, because we were and I wasn’t sure what she wanted beyond a new script.

“You made me the villain,” she hissed, dropping the cheer, anger flushed over insecurity like paint over mold.

“You cast yourself,” I said, not unkind. Just true. “I built a house. You tried to take it. Those are the lines.”

She looked at my cart. “Enjoy your little shack,” she said, as if we were still children and I had the smaller room because I had been born first.

“I do,” I said, and walked away because some grace does not include staying for the argument.

Ethan and I met for a beer one night because co-parenting is easier when you remind yourselves you liked the other person a little before the spreadsheet. “You look good,” he said. “Unknotted.”

“I changed the locks,” I told him. Then I laughed because that sentence did too much work and deserved a five-paragraph essay.

“I changed mine too,” he said at my look. “On my brain,” he added, tapping his temple. “Therapist makes me ask myself if the drama is also a hobby.”

“Good for you,” I answered and meant it.

Summer settled into the neighborhood. Our neighbor Mr. Leary transplanted his tomatoes late again and they still survived because the sun was merciful. My mother texted a photo of a jar of marinara with a crocheted cover that made me irrationally tender in a way that would have been less confusing if she had sent it three years earlier. I sent back: looks delicious. No exclamation point. I am learning that punctuation can be a kind of lie.

Norah’s school held a science fair. She built a model of our carriage house out of foam board and toothpicks. She wired a tiny LED that turned on when the roof closed properly. Her label read: load-bearing trust. When a boy in her class asked what it meant, she said, “It means sometimes grown-ups make rules because they love you, and sometimes they make rules because they like winning more than they like you.” His eyes widened. He said, “My dad does that.”

I got an email from the judge’s clerk six months after the hearing. A standard notice: injunction in good standing, renewal available within sixty days of expiration. I set a calendar reminder and breathed wherever breath lives in a body. People talk about forgiveness like it is a gift you hand someone wrapped with ribbon. I have learned I like mine with receipts.

In late fall, my mother and I sat on her back step and watched a squirrel attempt to carry an apple three times its size up a tree because this is the kind of documentary real life gives you when it’s feeling generous. She sipped tea from the mug I painted for her when I was twelve—the one where the glaze ran because I couldn’t afford the kiln time everyone else’s parents paid for.

“We were wrong,” she said. She did not make a performance of the sentence. “We were cruel,” she added, which felt like air changing pressure. “I wanted to fix something for your sister and I broke you instead. I thought if I kept talking I could make you believe me.”

“And if I stayed quiet,” I said, “I would.”

She nodded. “I am learning to be quiet in the other way,” she said.

The apology didn’t fix anything because that isn’t its job. It did make the ground stop moving under my feet long enough to decide whether I wanted to stand there at all. I said I was willing to try. She cried in a way that didn’t require anything from me and then talked about a casserole recipe because we needed somewhere to go that wasn’t a courtroom or a wound.

I went home and lay on the floor next to the heater vent and listened to the hum. Norah read a book about a girl who builds a bridge and tape flags to it. She tested its strength with the weight of three mandarins. When it held, she cheered quietly because she understands that some triumphs require reverence.

The sign on our front door is still the one she lettered months ago: Home. Underneath, smaller: no secret visits. I didn’t correct the capitalization. I never will. Rules you write at seven sometimes outlast case law.

At night, sometimes, I stand in the doorway and look at the place where my sister once stood measuring my walls with her eyes. The paint I chose is still the color of eggshells in shade and sunlight, not anything you could sell as trendy, but it does what it’s meant to: reflect what is true.

We have dinner at our little table most nights. Pasta on Wednesdays because I like the shape of Norah’s mouth when she says fusilli. We say things like “How was your day?” and she answers with descriptions of moments I will carry to my grave: a pigeon who walks like a boss, a teacher who used the word groovy, a friend who told her you can make a wish on a dandelion more than once and all the wishes still count.

Before bed, she checks the CO detector. Beep-beep. “Still working,” she says. “Still working,” I answer.

And that is the ending I offer you, if you need one: not a bang, not a violin swell, but a double tone in a small room that means something you built to keep you safe is doing its job. A judge wrote an order. A child played a video. A door locked with a sound you will know in your bones if you ever hear it at the right time.

Boundaries are not cruelty. They’re seat belts. And mine finally fit. If you’ve ever had to choose peace over approval, you are not alone. Closure isn’t a slam. It’s the quiet click that means your life has learned which way its doors swing—and who holds the key.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. My Sister’s Revenge Almost Cost My Son’s Life. Parents Said It Was Just A Game But Then…

My Sister’s Revenge Almost Cost My Son’s Life. Parents Said It Was Just A Game But Then… Part I…

CH2. My Niece Texted Me, “You’re Not Welcome At My Graduation. Stay Home, Loser.”

My Niece Texted Me, “You’re Not Welcome At My Graduation. Stay Home, Loser.” My Sister Added A Thumbs-Up Emoji. I…

CH2. My Wife Mocked Me in Front of Her Boss — I Left the Party, and That’s When Her Life Fell Apart

My Wife Mocked Me in Front of Her Boss — I Left the Party, and That’s When Her Life Fell…

CH2. My Family Said:”You’ll Firgue It Out” After Moving Away Without Me At 17—When I Made It, They Tried…

At seventeen I was abandoned by my family. I came home to an empty house and found only a note…

CH2. “There’s No Place For You Here!” My Daughter-In-Law Said On Christmas, So I Left. The Next Day…

“There’s No Place For You Here!” My Daughter-In-Law Said On Christmas, So I Left. The Next Day… Part I…

CH2. At Thanksgiving Dinner, My Sister’s Kid Threw His Fork at Me and Said, “Mom Says You’re the Help…

At thanksgiving dinner, my sister’s kid threw his fork at me and said, “Mom says you’re the help.” The table…

End of content

No more pages to load