My Parents Moved to Barcelona and Left Me With My Sister’s 6-Month-Old Baby — Then Came Back…

Part I — The Text, the Baby, and the Thing That Didn’t Break

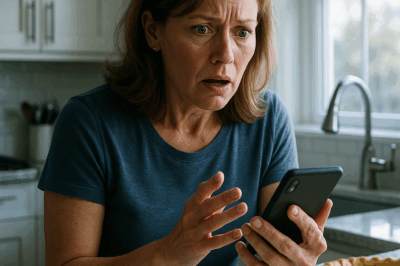

Alaa had just fallen asleep on my chest when my phone buzzed on the side table. I reached without looking, thumbed the screen to life, and read the six words that split my world in two:

We’re moving to Barcelona. I emptied the account. Good luck.

I didn’t move. Not for a full minute. Your body goes numb in self-defense before your brain can catch up. The baby’s weight anchored me to the couch—six months old, warm and trusting, fingers splayed soft against my collarbone. I opened the banking app and stared at zeroes that hadn’t been mine yesterday. The “shared family fund” we’d created when my sister’s life first unraveled—“for emergencies, any emergencies,” our mother had insisted—had always been held up as proof that we were all in this together.

Our mother had taken it all.

Alaa stirred, her mouth working in her sleep, a tiny sound escaping like the squeak of a door a child can’t fully open. I shushed her, not because she needed it—she was already drifting again—but because I needed to pretend someone could hear me.

“Thanks for the heads-up,” I whispered into her hair. She smelled like talc and milk and pure faith.

I called my mother. Voicemail. My father. Voicemail. My sister, Rania, who was supposed to be gone for a weekend to “rest and reset” after a Berlin débâcle none of us could define without using the word rehab. Read, no reply.

It wasn’t shock I felt. Not really. It was recognition. Being “the reliable one” starts so quietly you don’t notice the leash forming. It’s picking up your sister from ballet because Mom has a deadline—even though you have a club meeting. It’s folding Dad’s shirts because “Rania’s easily overwhelmed” and watching her overwhelm turn into reward. You tell yourself you’re being helpful and in doing so make yourself invisible. If dependability is a virtue, it also makes you easy to steal from.

I set Alaa gently in her travel bassinet. She sighed, flung both arms up in that newborn victory pose, and fell deeper asleep. I stood. Walked to the kitchen. Opened the drawer where I keep the printed files our mother mocked me for—“It’s all in the cloud, Danika.” I slid out last month’s statement: $18,327.42. Two weeks later: zero.

The fridge thrummed steadily behind me; the apartment smelled faintly of laundry soap and baby lotion and my own fear. I looked around. Bottles lined up like soldiers; diapers stacked in a pyramid; the pink sleep sack still damp in the laundry basket. Everything in the room belonged to someone else. Somehow it was all mine.

By instinct, I made a list. Formula runs. Immunization dates. Pediatrician’s name written in my sister’s harried pen. And then two lines I’d never expected to write before thirty: petition for emergency guardianship and freeze of shared account records.

There would be time later for rage or grief. Morning would come and with it a schedule Alaa didn’t yet understand and I didn’t yet master. For now, I sat beside her and listened to her breathe. The thing inside me that could have shattered—didn’t.

Alaa was six months old. She would need more than they had ever given. And I was, it seemed, the last adult standing.

Part II — The Shelf and the Crystal

People adored Rania because she was messy and luminous and impossible to hold responsible. She wrote poems on receipts and left them like breadcrumbs. She pivoted majors until the transcripts looked like confetti. She knows the bartender by name and the bouncer by nickname. Our parents loved her like she was rare crystal even when she shattered. Me—I was the shelf. The stable one. Strong. Replaceable.

We formed the family fund after Rania’s second ten-day inpatient stay. “We’ll support anyone in crisis,” our mother said, tongue heavy on the anyone while looking at me. I contributed more than I could afford—freelance copyediting, after-hours footnotes for a regional history journal—while they gave “in kind” (“Your father has a lecture in the spring, dear”). When she drained it the first time for a Catskills retreat (“transformative,” she said), we refilled it. Second time, for a move to Los Angeles to write a memoir she never started, we refilled it and added a rule. Then she fell in love and “had to” move to Berlin. Then she had a baby. Then Berlin collapsed. Then, on a humid Saturday, a text: We’re moving to Barcelona. I emptied the account. Good luck.

Stable children don’t get warning. That’s the point.

Day four of single-mom life: my body learned to function in narrow segments. Three naps of forty minutes if the gods were merciful, a two-hour rage-cry if not. I answered client emails at 2:10 a.m., fingers moving on autopilot while Alaa slept on a folded towel beside my laptop. Her breath fogged my forearm. Friends texted heart emojis. No one came. I was grateful and also tired of choreography that lets people feel supportive without risking proximity.

On Thursday, after pacing the floor with her strapped to my chest for two hours while she screamed into my clavicle, I opened the door to get the mail and found a warm Tupperware on the stoop, steam fogging the lid. A note tucked under the clip: You’re doing more than enough. Neat cursive. Mrs. Alls across the hall. We’d only spoken once before, about compost hours. That night, she knocked once, light, and handed me a folded quilt.

“I made it for the wrong-sized bed,” she said, voice flat as if this were commerce, not mercy. She didn’t ask to come in. She didn’t look around. She left.

It was the first time all week I felt seen without being assessed.

Part III — Spain, Power of Attorney, and the Quiet Kind of Fraud

I hadn’t set foot in my parents’ house since the day they left. It still smelled like lemon oil and self-satisfaction. I told myself I was there for formula, the bassinet, a bottle warmer. What I was really there for lived in the bottom kitchen drawer under the junk mail: a green folder labelled Spain.

Inside: six months of printed itineraries. Apartment lease in Eixample. Barcelona SIM cards activated. Timing like choreography. Behind them, a notorized form—my name, my address, my signature that was not my signature. Power of attorney for Alaa Quinn, 6 months old, granted to Danika Quinn indefinitely. They had made me her legal guardian without asking, without even pretending to ask. Tucked behind that: a bank statement. Withdrawal of $21,600 from the family fund two weeks prior. Destination: Meridian Trust, Private International Division.

This wasn’t a panicked exit. It was strategy. They’d hidden behind “Mom guilt” and “we need a break” and used a baby they did not intend to raise as cover. They expected me to do what I always did: absorb, then apologize.

Back home, I googled emergency guardianship Virginia and legal aid office. The receptionist did not look up when she said “take a seat.” The waiting room was a symphony of fluorescent. When Ephraim Road stepped into the doorway—tie slightly skewed, sleeves rolled, the kind of tired that belongs to other people’s emergencies—he shook my hand like mine wasn’t a case. That alone nearly broke me.

He read the documents. One finger tapped each page.

“They never notified you,” he said.

“No,” I said. “They texted three sentences and left.”

He nodded once. “Then this isn’t only guardianship. It’s potential financial betrayal. Depending on how the funds were classified, possibly fraud.” He explained the climb: petitions, sworn statements, a home visit, a judge whose calendar valued precision. Slow. Upright. Uphill.

“I can do uphill,” I said. “I’ve been awake for weeks.”

That afternoon I built a binder. Receipts, screenshots. Rania’s old texts that said “just the weekend,” and my mother’s final message—We’re moving to Barcelona. I emptied the account. Good luck. I labeled tabs until the edges cut my fingers.

Two days later, Rania finally called.

“You agreed,” she said without hello, voice cold as knuckles. “Don’t punish them just because you hate me.”

“I didn’t agree to guardianship,” I said. “I agreed to Saturday and Sunday.”

“Oh, stop dramatizing,” she snapped. “Mom and Dad are done carrying you, Danika.” Then she laughed, a sound with edges. “Imagine telling a judge mommy didn’t ask permission before giving you the only interesting job you’ll ever have.”

I recorded the call. Labeled it. Backed it up twice. I slept two hours that night because Alaa’s fever crept up, but I did not lie awake for my sister. Relief, I learned, sometimes looks like administrative order.

Part IV — “We’re Back. We Want to See Her.”

Three weeks later, on a Sunday morning that smelled like the end of summer, my phone pinged.

We’re flying back. We want to see her.

No apology. No explanation. Just a declaration, as if they were returning to collect luggage.

They arrived 72 hours later: our mother in a silk scarf that thought it was Parisian, our father in sunglasses still perched like a crown. Rania was not with them. They looked sun-recovered in the sort of way that only people without responsibilities ever do.

“You look tired,” my mother said in lieu of hello, eyes scanning the apartment like an appraisal. “Still only working part-time?”

“You emptied an account for a baby you didn’t intend to raise,” I said. “Tired was inevitable.”

She tutted at Alaa’s posture in the high chair. “You’re not doing enough tummy time.”

“I filed for full custody three weeks ago,” I said, calm enough to scare myself. “I also filed to freeze the transferred funds and challenge the power of attorney on the grounds of non-consensual designation. We have a court date on Thursday.”

They went very still. Then my mother performed disappointment like opera. “There’s no need to escalate,” she said. “We’re family.”

“It’s already escalated,” I said. “I just stopped pretending it wasn’t.”

They left with the silence of people who believe sound can be evidence.

A judge in a room that smelled like wood polish and time reviewed our binder and raised her eyebrows once at the offshore transfer. “Miss Quinn,” she said, “I’m granting you full legal and physical custody pending review. The account is frozen. Any visitation will be supervised.”

My mother opened her mouth. The judge lifted her palm without looking. “We’re done.”

Outside, the wind lifted the edges of my shirt like a reminder. Alaa laughed in her stroller at nothing in particular—the way babies do when gravity forgets to apply to them for a second. I cried in the elevator because my body insisted on keeping records my head did not honor.

Part V — What Came After the Paper

Every morning now, the kiln hums at low heat in the studio I rented two blocks from home. Clay listens when nothing else does. It lets you press the day’s remaining chaos into seams your hand knows how to smooth. Alaa stands at my knee in a ridiculous foam crown and bangs a wooden spoon against a bowl I gave up on three nights ago. She is learning volume. I am learning quiet.

Mrs. Alls comes every Friday with cookies wrapped in wax paper and a book recommendation she knows I’ll never read but suggests anyway. “You can page it while you wait for glaze,” she says. Sometimes I do. Most times I fall asleep with my cheek against the cool table for 12 minutes, which is precisely the length of Alaa’s new universe.

Ephraim emails updates in his exacting, merciful way. The account stays frozen. Rania sent one email—how dare you—and received one reply from him, the legal kind that ends in a period that feels like a locked door. My parents have not contacted me since the courthouse steps, where my mother said, “You’ve always been jealous.” It is a relief when villains remain cliché. It makes your therapist’s job easier.

On a Wednesday in late fall, Alaa takes three steps between the wheel and the door, then falls on her diapered butt and laughs like gravity is comedy. I give her the wooden bowl with the thumbprint she made by accident. We have lunch: apples slices, cheddar cubes, crackers I pretend are artisanal because the box says they are. She naps; I trim mugs; the kiln ticks like a patient heart.

I write a letter to Rania. I tell her nothing she doesn’t already know. I tell her nothing she can weaponize. It’s a map with no landmarks.

Alaa is safe. She likes the blue spoon and hates the green one. She loves when the dog across the street sneezes. She falls asleep best when I hum off-key. I am not your enemy. That title is a costume you give out at parties. I am your sister. I gave your daughter my name at the courthouse because you did not show up. I hope you figure out how to want what is good for you.

I fold the letter and do not mail it.

Part VI — When They Came Back Again

They come once more in winter. Not to the apartment. To the studio. I know because the bell above the door rings differently when regret enters. My mother wears navy; my father clutches a scarf like prayer beads.

“We won’t take much of your time,” she says, which is how people ask for your whole morning.

“We want to see her,” my father says, voice softened into a request it never learned to be when I was eight.

“My lawyer will schedule supervised visitation,” I say, wiping my hands on a towel. “If that’s still your request in three months.”

“And you,” my mother says, sharp, “is there anything left in that house that remembers you were raised?”

I tilt my head. It is a question with a knife inside.

“Everything I was raised with is right here.” I gesture to the bowls, the spoon in Alaa’s hand, the shelf I built that does not buckle, the kiln that hums because I feed it patience.

My mother looks around the studio as if the clay might apologize for me. “You were always so—so stubborn,” she says finally.

“I was always so alive,” I answer.

They leave without striking. The restraint almost makes me sad. It would be easier if they threw something. It would make better theatre. But real endings are quieter. The door closes. The kiln ticks. Alaa sneezes and laughs. The dog across the street sneezes back. We laugh together, three bodies in conversation with air.

Part VII — What I Kept, What I Learned

Alaa’s first birthday is small on purpose. Mrs. Alls brings a cake the size of a library book and a candle shaped like a question mark. Ephraim and his wife stop by after court with a wooden puzzle. Two moms from the park stay for an hour and take photos that make my apartment look like a postcard. We sing and then we don’t. Alaa smashes frosting into the grout lines and calls it joy.

That night, after she finally surrenders to sleep, I stand in the doorway and watch her breathe. I didn’t know how to do any of this four months ago. I am still learning. I am entirely, shockingly competent at it.

I sit at the wheel and guide clay into a bowl that will hold raspberries in June. I think about the text that started all of this, about the folder labeled Spain, about the thousands shifted offshore with the click of a mouse by two people who taught me discipline like a mirror and love like a ration. I think about how easy it would be to become them in reverse, to write my pain as policy and call it protection.

I don’t.

My policy is smaller: airtime belongs to the person who changed the diaper at 3 a.m. Boundaries are what you give a child so a child can give them to herself when she is 25. Stability isn’t stagnation; it’s a platform for joy. The shelf doesn’t hold crystal anymore. It holds bowls we made, with dents her thumb gave them.

The kiln cools to a purr. The studio smells like warm earth and sugar.

I text Mrs. Alls a photo of the cake crumb war aftermath. She sends back a heart and then a question mark and then “I have a mop if you refuse to have one.” I send back a laughing emoji because I have three.

I whisper, to no one in particular, to the woman I was on the couch four months ago with a baby sleeping on her chest and bank app open on her phone: You did it.

When they left, they thought they left me with a baby and a bill and a grief they didn’t plan to witness. What they actually left me with was a life I built on purpose.

They came back. The law did its job. The kiln does its. The baby grows. And me—I am the shelf and the crystal, the bowl and the hand that shapes it, the woman who refuses to be the inheritance you steal when the ticket to Barcelona goes on sale.

I am not the interesting job they gave me. I am the mother I chose to be.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. At her family reunion, someone joked: “Are you two happy together?” My wife laughed: “Happy? I regret this marriage every day!” her family burst out laughing -until I smiled and said, “Me too. That’s why I’m ending it -today.” The room went silent.

At her family reunion, someone joked: “Are you two happy together?” My wife laughed: “Happy? I regret this marriage every…

CH2. When I threw away the child seat my mil gave us, my hubby yelled, ‘Mom gave that to us!”

When I Threw Away the Child Seat My MIL Gave Us, My Husband Yelled, “Mom gave that to us!” Part…

CH2. My Wife Texted Me at 2 A M , “Can’t Talk Now, I’ll Call You Later ” By 2 10, She Walked In—Shaking.

My Wife Texted Me at 2 A.M., “Can’t Talk Now, I’ll Call You Later.” By 2:10, She Walked In—Shaking. Part…

CH2. Ten Days Before Thanksgiving, I Found Out That My Daughter Was Planning To Humiliate Me…

Ten Days Before Thanksgiving, I Discovered Something That Shattered My Heart — My Own Daughter Was Plotting to Humiliate Me…

CH2. On My Birthday, I Learned They Took More Than Just My Gifts — What Happened Next

On My Birthday, I Learned They Took More Than Just My Gifts — What Happened Next Part I — The…

CH2. My Dad Removed Me From the $30K Dubai Trip I Funded—To Give My Spot to My Brother’s Fiancée

My Dad Removed Me From the $30K Dubai Trip I Funded—To Give My Spot to My Brother’s Fiancée Part I…

End of content

No more pages to load