My Parents Left Me Alone in a Coma at the Hospital — But When They Saw Me in Court, They Broke Down

Part I — Visitor Logs and Empty Chairs

I was in the hospital recovery room six weeks after waking from my coma when my lawyer slid the visitor logs across the table.

“Your parents visited once, the day you were admitted,” she said. “Your brother never came at all.”

I stared at the empty pages like they were a mirror. The nurse pushed open the door with her hip, a plastic pitcher sweating in her hands. “Your mother called again,” she said gently, eyes flicking to the chart. “She asked about your insurance payout.”

They’d left me to die, but they never stopped asking about my money.

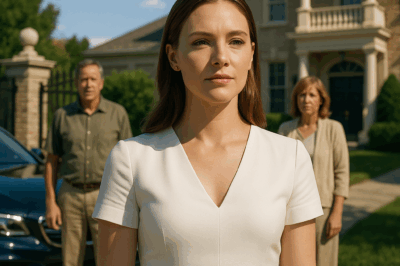

My name’s Charlotte. I’m twenty-six. Before the accident, I was a physical therapist at a rehab center—joint mobilizations, gait training, fall-prevention classes, a body addict who believed in the gospel of movement. Three months ago, a drunk driver turned left through a crosswalk and rearranged my life. Traumatic brain injury. Shattered clavicle. Ribs like cracked piano keys. Medically induced coma for five weeks, then one week of slow surfacing, hands squeezing at ghosts.

My family was a scattering of addresses and holiday texts. My parents divorced when I was nine and remarried other people who liked different restaurants. My older brother, Derek—thirty-two, sales—spoke in small talk and invoices. I lived alone in a small condo my maternal grandmother left me, the only person who had ever shown up without an agenda. I had savings, good health insurance through work, a $150K life-insurance policy, and a will that still listed my parents as next of kin because I hadn’t gotten around to updating it.

I wasn’t rich. I wasn’t famous. But I had something they wanted. And I was unconscious.

They were my emergency contacts—defaulted from a childhood nobody remembered kindly. They arrived the day of the accident—separately, because even disaster didn’t heal their divorce. A social worker explained the coma. Decisions might be needed. My mother had medical power of attorney by default. My father stood beside the vending machine and did not cry.

Week one, they came a few times. My mother’s voice was sugar over anxiety. My father’s questions were hands in pockets. Derek showed up once, stood in the doorway like guilt in a good suit, and left after ten minutes because he “didn’t want to get in the way.”

Ryan—my partner of two years, fellow PT—showed up every day. He brought playlists labeled Charlotte’s Awake Mix and Charlotte’s Asleep Mix because hope needed a protocol. He stretched my fingers gently so my tendons wouldn’t hate me when I returned. He talked to me like the coma was a bad connection, not absence: You got this. Jess says the new patient tried to high-five her with the wrong hand. I told Dr. Kumar you hate hospital socks; he said you can file a complaint when you’re upright.

Jess—my best friend, co-worker, sworn enemy of glitter—was there constantly. She taped cards from my patients to the wall: Hurry back, you bossy angel. They read poetry into the air and squeezed lotion into hands that didn’t know how to ask for comfort.

The nurses noticed a different rhythm. “Are you family?” one asked Ryan.

“I’m her partner,” he said. “Two years.”

Her voice dropped. “Her parents haven’t been here in five days.”

By week three, my mother’s questions moved from How is she? to How does life insurance process? A nurse overheard her on the phone in the hallway: “If she doesn’t make it, Derek and I split everything, right?” The nurse wrote it down because nurses write down everything. The chart—my body’s diary—started including sentences about ethics.

Week four, Derek returned—not to the room, to the admin office. He asked the administrator about organ donation timelines, cremation versus burial, what paperwork “we’d need if the machines were turned off.” “She’s still alive,” the administrator said. “These conversations are premature.” Derek said he was being “practical.” He used the word like it was a blanket that could cover anything.

Week five, my fingers fluttered in water like minnows. My eyes tried on light. The doctors were cautiously optimistic. The hospital called my parents. It took two days for either to return the call.

Ryan was there when I opened my eyes. “Hey,” he said, crying like he’d snuck tears into the room and was apologizing. He put my hand on his cheek like a landing.

The awakening took days. There is no switch. There is a dimmer. I learned to swallow again like it was a foreign language; my throat filed a complaint. A nurse told me gently: “Your parents haven’t visited in over a month—but they’ve called several times about insurance and assets.” The heart monitor beeped louder like it wanted a turn.

Ryan slid a chair close. His hand was warm and factual. “I need to tell you something,” he said. “Derek tried to get power of attorney transferred while you were sedated. He said it was for bills. The social worker blocked it.”

The hospital provided the visitor logs when I asked. Their silence was a table of contents. My parents: three visits total in six weeks. Derek: one, never into my room. Ryan: every day, multiple hours. Jess and co-workers: dozens of visits.

I cried until exhaustion did what sedation no longer could.

Then my bank called. Fraud department. Calm voices. Questions. “Someone used a forged power of attorney to try to access your accounts,” the woman said. “They attempted to transfer $40,000 from savings. We blocked it. The signatures don’t match. The notary doesn’t exist. We’ll send everything.”

Handwriting analysis confirmed it: Derek’s slanted arrogance. The IP address came from his townhouse. Meanwhile, my life-insurance company had a log: my mother called twice requesting details on beneficiaries and timelines. “She asked if a vegetative state ‘counted,’” the rep said, stumbling on the word like it had teeth.

When I was strong enough for visitors, my mother arrived with supermarket flowers and mascara tears.

“I’m so glad you’re okay,” she whispered.

“You haven’t been here,” I said. It came out like a fact, not an accusation, because facts are restful.

“I was so worried,” she said. “I couldn’t bear to see you like that.”

“Ryan was here every day,” I said.

“He’s not family,” she snapped, as if DNA were a credential and not an accident. “We were handling important things.”

“Like forging my signature?” I asked.

Her face changed shape. “Derek was trying to help,” she said, finding the lifeboat she thought would float.

The nurse stepped in and asked my mother to leave because the monitor was tattling. At the door, my mother said, “We’ll talk when you’re thinking clearly.”

Then she started making phone calls—to aunts, cousins, anyone whose approval tastes like anesthesia. She’s confused from the brain injury, she said. She’s accusing us of terrible things. We were always there.

An aunt called me: “Your mother is so hurt.”

“She tried to pull my life support,” I said.

“That can’t be true,” my aunt said, because truth is sometimes less believable than the story you want to be true.

I realized I needed to do what I do with patients who are learning to stand: protect the joint, strengthen the core, document everything, and refuse to fall without trying.

Linda, the hospital social worker, sat in a plastic chair by my bed and listened like it was her job, because it is. “We see this more than you’d think,” she said. “We call it Financial Opportunism During Vulnerability. Not a medical term. The medical term is nauseating.” She introduced me to Patricia—a lawyer with steel in her vocabulary and gentleness in her file tabs—who specializes in medical exploitation and elder abuse, two circles that overlap too often because greed doesn’t care about demographics.

Patricia flipped through the stack Linda had compiled. “Visitor logs. Security footage. Bank fraud reports. Insurance recordings. Journal entries from your partner.” She smiled—flat, satisfied. “They thought the coma would be a cloak. They didn’t notice all the cameras.”

“What do I want?” I asked, because knowing your goal changes your gait.

“Protection first,” Patricia said. “Accountability second. Precedent if we can get it.”

I closed my eyes. “I want them away from me,” I said. “I want them to learn to keep their hands off the sick.”

“Then let’s make sure they can’t reach over this bedrail to touch anyone else either,” she said. “We’ll build a case they’ll feel in their bones.”

Part II — The Paper Trail and the Pulse

What my parents and Derek didn’t know was this: the hospital had written everything down. Linda had flagged “concerning behavior” at the end of week two. The notes read like a morality play, except the clinicians refused to guess motives; they just recorded actions.

Week 1: Parents present at admission. Discussed medical updates appropriately.

Week 2: Parents’ questions shift to finances. Mother asks about insurance coverage and “death benefits.” Father asks “what happens to her assets if she doesn’t wake up.”

Week 3: Mother on phone in hallway: “If she doesn’t make it, Derek and I split everything, right?” Nurse documented verbatim.

Week 4: Derek meets admin to discuss organ donation and “arrangements.” Does not enter patient’s room.

Week 5: Hospital leaves multiple messages. No response. Partner visits daily.

Security footage showed Derek in a pressed shirt, leaning against the wall across from my door, scrolling. He took two calls. On the second, he said, “This is taking forever. The insurance said…” A clip with no sound is still a documentary when your body knows context. The admin staff’s notes—cameras for paperwork—said he attempted to switch medical POA to himself; the hospital refused.

The bank’s file held the forged power of attorney with my name slashed wrong, dated two days before their attempted withdrawal. The notary’s stamp belonged to a dead woman. The IP address traced to Derek’s condo; the bank saved the login attempts and the timestamps and the bio of his internet provider like a recipe for charges.

The life insurance company’s recordings were worse than I’d braced for. My mother’s voice was soft, the way you speak when you want to be taken seriously by people who can tell you no. “If she is in a persistent vegetative state, does that count?” she asked. The rep paused long enough that you can hear a decision: Flag this account.

Ryan’s journal—spiral-bound with coffee stains—logged everything he saw. Times. Who entered. What was said. What wasn’t. He had learned from me—you make a plan, you write it down, you follow it. He wrote, 3/15: Her mother asked about death benefits again. Nurse looked disgusted. Charlotte’s pupils more reactive today. He wrote, 3/21: Derek came and left without going in. Admin told him to stop asking logistical questions that were “inappropriate.” Charlotte’s hand warm in mine.

Patricia compiled. She sent a firm letter to Derek and my parents informing them of upcoming actions and instructing them not to contact me. She filed for a temporary restraining order against Derek and a civil suit for attempted fraud and exploitation. Against my mother, she filed civil claims for emotional distress and attempted exploitation, and a restraining order that would become permanent if my vitals spiked when she entered a room: the new measure for who gets to visit is the heart monitor.

My mother received the papers and called my cell phone fourteen times in one afternoon. By the eighth voicemail she was crying. By the twelfth she was angry. By the fourteenth she was exhausted and manipulative. “You’re suing your mother?” she said. “I was trying to ease your suffering.”

“You were trying to ease your way to a payout,” I said—to the empty room, because I did not pick up.

Derek texted: This is insane. I was fixing your bills. You’ll regret this. I screenshot it, saved it to a folder named Exhibit.

My father, who had been a polite ghost throughout my childhood, sent an email with the tone of a disappointed manager: Your mother and brother made mistakes, but this is excessive. Drop the lawsuit. I printed it and filed it in Noise.

They hired a lawyer—expensive, good. He asked for discovery. Patricia sent a box. He called a week later to encourage settlement. My mother refused. “She’s my daughter,” she told him, like the word daughter was a deed. Derek said, “It’s her word against ours. She was in a coma.” The lawyer doesn’t get paid to educate clients. He gets paid to show up in court and watch them learn.

Patricia coached me like she was prepping me for a marathon I didn’t sign up for but deserved to finish. “They’ll argue confusion because of the brain injury,” she said. “They’ll imply your partner wants your money. They’ll ask why you didn’t update your will.” She looked at me the way Linda had. “Are you ready for that?”

“I’m ready,” I said, because the alternative was staying in the hospital bed in my mind forever.

The night before court, my mother left one more voicemail. “Please don’t do this. You’re tearing this family apart.” I saved it to a drive labeled Pulse—because my vitals were set by what I believed now, not by her meter.

Part III — The Day the Monitors Spoke

Civil court is small, fluorescent, more honest than TV. There are no grandiose speeches, just exhibits and patience and the quiet brutality of a judge who has seen every kind of family do every kind of thing.

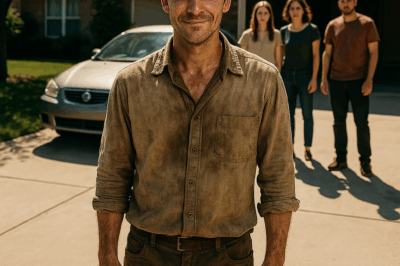

I rolled in a wheelchair because stairs and I were on a trial separation. Ryan sat beside me, his hand a general anesthesia I allowed. Jess sat two rows back in a dress that said don’t test me. Linda sat in the aisle with a brown folder; her eyes were kind and iron. My parents sat with their lawyer. My mother wore navy. My father wore apology like a borrowed suit. Derek wore a tie you could sell cars with.

Patricia presented first. No scenery to chew, just a spine of facts.

Visitor logs on an overhead: three visits by my parents in six weeks; Derek, one bubble on a calendar with the note never entered. My mother stared at the table the way people stare at coffins.

Security footage: Derek with his phone, the hallway carpet holding other people’s footsteps; the admin’s note about his “inappropriate logistical questions.” Derek’s lawyer objected; the judge allowed it; the video had timecodes.

Bank evidence: forged POA with Derek’s slanted signature; attempted transfers; notary stamp belonging to a woman who hadn’t been alive since 2016; IP addresses written like math. Derek can sell anything, but he could not sell this; silence bought him nothing.

Then Patricia played the life-insurance call. My mother’s voice in the courtroom was not the mother voice I remembered from bedtime stories. It was crisp, transactional. “If she is in a vegetative state, does that count?” she asked. Gasps. Someone in the back said oh my God quiet enough the bailiff didn’t care. My mother collapsed into tears that made no sound. “I was asking questions,” she said. “I didn’t know.” The judge held up a hand and wrote something down.

Linda took the stand. She spoke the way people speak when their notes are good. “We flagged the family in week two for concerning behavior. We documented phone calls asking about finances, not health. We documented the guardianship attempt. We blocked it.” She did not editorialize. She did not need to. The documentation had already chosen a side: mine.

A nurse testified, voice trembling at first then steady. She recalled my mother’s hallway call about splitting “everything,” her own discomfort, the way Ryan’s presence soothed the room. “He brought her lotion and music,” she said, tilting her chin toward Ryan. “He treated her like a person.”

Ryan testified and did not cry. He read from his journal. He described a room that learned to know him. Derek’s lawyer tried to discredit him. “You’re not family,” he said.

Ryan looked at him the way you look at a broken treadmill and don’t get on. “I was the one who stayed,” he said. “That’s family.”

Then Patricia called me. The judge asked if I needed a break. I shook my head. The microphone tasted like metal. I told the truth like it was physical therapy for my life: one difficult rep at a time. I described waking into a world where I had to relearn the alphabet of my body and the vocabulary of betrayal. I described reading visitor logs the way some people read obituaries. The judge asked a question a human asked, not a judge: “How did it feel to learn your family had left you?”

“Like I was already dead to them,” I said. “Like I only mattered as a number on paper.” My mother sobbed. My father stared at the floor. Derek’s jaw clicked.

Derek’s lawyer asked, “Do you really think your family wanted you dead?”

I looked at my brother like I might once have looked at a mirror if it could have answered me. “You forged documents to get my money while I was unconscious,” I said. “What would you call it?”

He didn’t answer. The question stayed in the air like a fire alarm.

The judge took an hour. Civil court justice isn’t dramatic. It’s tidy when it can be. She returned and read like she was adding up a bill.

“In the matter of attempted fraud,” she said, looking at Derek, “the evidence is clear and convincing. Restitution plus fines, totaling $38,000. Community service at a hospital not your sister’s.” She looked at my parents. “In the matter of emotional damages and attempted exploitation, liability is proven. $75,000 in damages.”

She signed the restraining orders. “No contact without the plaintiff’s expressed consent,” she said. “Violation will be considered contempt.” She cleared her throat once, like a human, and looked at the gallery. “What happened here is a violation of trust in an hour when there should have been nothing but protection.”

My mother folded like a paper crane. My father’s face tried to be stoic and failed. Derek’s fury made a small weather system around him.

I didn’t feel victorious. I felt like someone had set down a bag I had carried half-conscious for months. Ryan squeezed my hand. Jess exhaled a profanity she meant as a blessing. Linda closed her folder and looked at me like she was handing me a medal with her eyes.

After the judgment, I went home and slept thirteen hours. When I woke, I felt the edge of my body where it meets the world and recognized it as mine.

Part IV — The Work of Standing

Recovery is a boring miracle. It’s clamps and metronomes and sweat. I went from wheelchair to walker to cane with the obsessive focus of a clinician who had become her own case study. The irony of doing balance training in front of co-workers did not kill me. It pushed me. Ryan counted reps, then hid the whiteboard when he saw me turning them into religion.

Jess and our co-workers threw me a party when I got cleared to work part-time—cupcakes, balloons that said YOU DIDN’T DIE because Jess doesn’t understand subtlety and I needed that. Patients who had watched me hobble by in the hallway now high-fived me with the correct hand. A man who had learned to say th again after a stroke said, “You came back,” and I said, “So did you,” and we cried like professionals.

My mother sent one email. I’m sorry. I was scared and made terrible choices. I hope someday you can forgive me. I didn’t respond. Forgiveness is a muscle. I’m still rehabbing. Derek didn’t apologize. He disappeared into the quiet you choose when you’ve run out of arguments. My father sent a card on my birthday. I should have protected you. I failed. I appreciated it the way you appreciate a sign that points in the right direction after you’ve already arrived.

Some cousins took sides the way people pick teams they think will win. That’s their religion. It’s not mine. My religion is who shows up with soup.

I updated my will. Ryan is my primary. Jess is my medical power of attorney because she has a voice that makes surgeons return calls and knows what I want without moralizing it. I wrote down everything: no heroic measures without a neurologist signing a paper that says she would want this because it will return her to herself. I named a contingent beneficiary in case of weird news. I gave the Foundation I picked enough money to build something and my grandmother’s church enough to stop asking. I made a folder titled If/When and told Ryan where it lives. “Morbid,” he said.

“Practical,” I said. It turns out you can reclaim words.

Six months later, I went back full-time. On Thursdays I speak to new nurses about the ethics of family contact and what to do when the people at the bedside are dangerous. I talk about medical POA and living wills and the miracle of documentation. I show them my visitor logs. I tell them, “Write everything. Believe what people show you. Love who stays.”

I filed the court orders in a drawer with the patient thank-you cards and my grandfather’s watch. I do not look at them often. I do not need to. Their power exists whether I admire it or not.

Ryan and I adopted a dog with too much energy and a fear of blenders. We named her Cello because the joke made us laugh even on tired days. We take her to the park and pretend it’s training. It’s actually joy.

On the anniversary of the accident, I walked the crosswalk where my body learned what metal means and put down a small bunch of grocery store flowers because every ritual counts if it makes the air easier to breathe.

That night, I wrote a talk for the hospital’s patient advocacy seminar. I titled it The Work of Standing. I ended it like this:

I used to think family was who had keys to your house and your blood in their veins. Now I think family is who shows up when you can’t speak for yourself—and who asks the doctor about your pain score, not your policy. Protect yourself. Put it in writing. Choose your people. And when someone tells you who they are, write that down, too.

My parents left me alone in a coma at the hospital. They broke down in court when the monitors of truth spoke instead of me. I didn’t win anything there that I hadn’t earned by surviving. What I gained came after: a life with boundaries, paperwork that doesn’t tremble, a partner who presses his cheek to my palm and says, “You are here.”

If you need the sign I needed months ago, here it is: the people who stay when you can’t fight for yourself are the only ones who get a vote. Protect yourself legally. Update your will. Choose your people carefully. The rest is noise.

The End.

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. We Left My Foolish Husband Far From Home as a Joke But When He Came Back It Wasn’t Funny…

We Left My Foolish Husband Far From Home as a Joke But When He Came Back It Wasn’t Funny… …

CH2. They Ditched Me at 13—But When I Became an Heiress, They Suddenly “Remembered” Me

At 13, they ditched me, leaving me alone with nothing but rejection and cold silence. Years later, when I became…

CH2. My Dad Sent A Message To Family Groupchat: “Stay Away From Us Forever”-But After I Remove…

My Dad Sent A Message To Family Groupchat: “Stay Away From Us Forever”—But After I Remove… Part I — The…

CH2. The Night Before My Wedding, My Parents Drugged Me and Shaved My Head—But Next Morning THEY Trembled

The Night Before My Wedding, My Parents Drugged Me and Shaved My Head—But Next Morning THEY Trembled Part I —…

CH2. I sat in my son’s ice room after his car accident. The surgeon said, “His chances of recovery are minimal.”

I sat in my son’s ICU room after his car accident. The surgeon said, “His chances of recovery are minimal.”…

CH2. My Family Broke In With Baseball Bats When I Refused To Sell My House And Pay Their $150K Debt…

When my parents cut me off for five years because I refused to sacrifice my $120,000 life savings for my…

End of content

No more pages to load