My Parents Kicked Me Out in a Blizzard. They Said I’d Come Crawling Back, But Then…

Part I — The Call

When my phone rang at 6:47 a.m., I almost didn’t answer. Unknown number. Early hour. The old instinct to let things go to voicemail tugged at me. But something in the silence between rings made me swipe.

“Is this Ellen Ward?” a soft male voice asked.

“Yes,” I said, still half asleep.

“This is Dr. Finch from Meadow Ridge Assisted Living. I’m afraid there’s been an incident involving your father.”

That word reached under my ribs and tightened. My father. The man I hadn’t spoken to in thirteen years. “What happened?”

“He was found outside early this morning, disoriented and bruised. We believe he tried to leave the facility on foot.”

“Is he—”

“He’s stable now,” Dr. Finch said gently. “But he keeps asking for you.”

There it was, the old, suffocating compression of air. The coil that used to live in my throat when a door in our house closed too hard. I thanked him, ended the call, sat on the edge of my bed, and stared at the paint crack that looked like a branching river. Habit said don’t go. Pity—and something else I didn’t want to name—made me move.

By the time I reached Meadow Ridge, a pale sun was starting to smudge the frost off the grass. Inside, the receptionist’s smile had the careful contour of someone who delivers difficult news often.

“Mr. Ward’s daughter?” she asked.

I nodded.

“He’s in 214. He’s been asking for you all morning.”

The hallway smelled like cleanser and winter air tracked in on rubber soles. Outside someone’s door, two caregivers were laughing softly—the kind of laugh that keeps you alive when the world is endlessly serious. I reached 214 and paused. My hand hovered over the handle. I opened the door.

He looked smaller than my memory allowed. The man who once filled a doorway with his anger now barely filled the thin blanket. His face had collapsed into itself; even his hands were uncertain on the sheet. He saw me at once.

“Ellen,” he rasped. “You came?”

I stayed standing. The room was too tidy, the flowers too generic. “Yeah,” I said finally, and lowered myself into the chair by his bed.

“They said I tried to leave,” he chuckled, and it sounded like gravel. “Guess I forgot I’m not twenty anymore.”

“Why?” I asked.

He looked past me, out at the gray scrap of sky between brick and fir. “I wanted to find you.”

My breath snagged. “You did?”

“You moved, changed your number. I figured if I started walking, maybe I’d find my way back somehow.” He smiled, the ghost of an expression I recognized and disliked. “Still better than sitting here. These walls don’t let you think straight.”

We sat with the hum of forced air and the ache of old furniture. Somewhere down the hall, someone was crying. He cleared his throat.

“I know what you think of me,” he said. “I earned it. But before I go, I wanted to see you once more.”

“You’re not dying,” I said too sharply.

“Not yet,” he allowed. “But the clock’s getting louder.”

He’d always been like that: riddles instead of apologies. I hated it as a kid. I hated it now.

“I didn’t come for a deathbed apology,” I said.

He nodded. “Figured. But you came anyway.” He coughed; it rattled through his chest in a way that made me want to get a nurse and made me stay seated instead.

“I kept your letters,” he said.

My stomach knotted. “What letters?”

“The ones you sent after you left. The ones I never answered.”

“You… read them?”

“Every one.” He took a breath like it cost him. “Burned them last year. Thought if I did, maybe I could let go.”

Something hot flashed under my skin. “You don’t get to let go,” I snapped. “You don’t get that clean.”

“You’re right,” he said simply.

We let the quiet press down. I stood, paced to the window, watched an old man in a wheelchair gaze up at the silver morning like it was a masterpiece. I envied him.

“You look like your mother,” my father murmured.

“Don’t,” I said without turning. “Don’t bring her into this.”

“She’d want you to forgive me,” he said. “She’d want me to have been someone worth forgiving.”

It was the first true thing I’d heard him say in years.

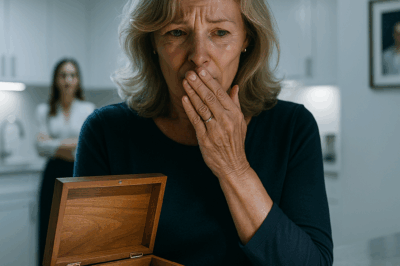

A nurse came and went, kind hands, efficient voice. When she left, he asked me to get a worn wooden box from under his bed. Inside: photographs, curled at the corners, sun-faded colors. My mother on the porch steps, hair caught by wind, a baby tucked in a yellow blanket.

“That’s you,” he said. “She’d make that face looking at you—like the world was… safe.”

“She looked happy,” I said softly.

“She was,” he said. “Until I started breaking everything.”

He rubbed his thumb over my mother’s face in the photograph like it could wipe away what he’d done later. He put the picture back.

“You don’t have to forgive me,” he said. “I just wanted you to see me like this. Not as a monster. As a man who broke things he couldn’t fix.”

I didn’t say that monsters are just men other people have loved.

When I stood to leave, he didn’t reach to stop me. He only said, “Thank you for coming.”

The air outside tasted like wet iron. I sat in my car until the fog on the windshield cleared itself. My phone glowed in my palm like a small decision. I scrolled to Clara’s number and pressed call.

“You saw him,” my sister said without hello.

“Yeah.”

“Is he dying?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “Maybe.”

“You sound different,” she said. “Like you stopped running.”

Rain stitched quiet lines across the glass. “Maybe I did.”

Part II — The Night of the Blizzard

That winter I left, there was a blizzard. The kind of storm the news names like a person. I was sixteen, and the house had been on edge all day. My father’s side business—a thing he thought was noble and the law called shady—was unraveling. My mother’s mouth was a hard line that might never soften again. Clara had already moved out, a year earlier, after a fight that began with the word no and broke a door.

We were eating dinner in silence. My fork scraped porcelain. My father’s gaze pinned me the way a moth recognizes light as danger.

“You think you’re grown now,” he said finally.

“I think I know how to clean this whole house and still get a B on a geometry test,” I said without looking up.

He stood. The chair leg screamed across tile. “Pack your things.”

My throat closed. “It’s dumping snow.”

He smiled—a small, cruel wasted thing. “Then wear your boots.”

My mother looked at her plate like it was a mirror she needed to avoid. “Don’t make a scene, Ellen,” she said. “You’ll come crawling back.”

I went to the closet that wasn’t a bedroom and put my what-ifs into a backpack. It’s shocking how small a life can look when it’s been tidy for strangers. I layered socks, found the boots Grandpa had bought me two winters before and my father had mocked, pulled on a coat too thin for this kind of night, and stood with my hand on the doorknob.

“You won’t last the week,” my father said.

I turned. “You don’t get to decide that.”

The door opened into a world that roared. The snow stung. The streetlights were halos without angels. I walked.

At the end of our block lived a woman named Mae who smiled at everyone like her face knew how to do only that. She ran a diner—Mae’s—open any time the cops needed coffee or the lost needed warmth. I had cleaned her windows after school for small bills and big praise.

The bell over the door sounded like a reprieve. A handful of truckers glanced up. Mae took one look at me—white as the world outside, soaked through, breath like smoke—and came around the counter.

“Sit,” she said, pushing a steaming mug toward my hands. “Don’t argue.”

“I—please—can I have a job?” I chattered. “Any job. I can clean, mop, serve—”

“You can have stew first,” she said. “Then we’ll talk.”

Mae put me in the back booth, under the framed photo of her with three children in Halloween costumes from a year that looked like the eighties. I wrapped my fingers around the mug and watched the snow thrash. When the plate of stew hit the table, my body remembered hunger in a way my mind had been denying for years.

“You coming back?” she asked without looking like she was asking.

“They kicked me out,” I said. “Said I’d come crawling back.”

“People say a lot of things when they need to hear themselves,” she snorted. “I’ve got a spare cot in the office. It smells like onions and printer ink. It’s yours ‘til you figure out better.”

The truest kindness is practical. I cried that night in the cot because the room smelled like onions and printer ink and safety. Mae pretended not to hear. In the morning, she handed me a towel and a yes.

I learned that winter how to tilt a plate so the gravy didn’t drown, how to hear a person’s day in the way they said “coffee.” When the blizzard finally exhaled and the city remembered how to move, I took the bus to a shelter and to a school and to a cheap room with four other girls who hid bruises with laughter and could make a feast out of a box of pasta and a jar of thrift-store olives.

Mae wrote me a reference letter. I got a housekeeping job at a hotel with a manager who ran on lists and kindness. I slept, worked, studied, counted tips like votes. I graduated high school. I wrote my father a letter the night I got my diploma. I did not send it.

I did send letters the first two years I was gone. They were not apologies. They were dispatches from survival. I filed taxes. I bought boots. I burned the last photograph I had of you because I don’t need proof you existed to know that I do. None were answered. I stopped writing.

Mae taught me about yeast. “It’s a living thing,” she said. “Like hope. Feed it. It feeds you.” She loaned me five hundred dollars and said, “Start your ridiculous bakery, girl.” I paid her back a year later with a check and a cinnamon twist she said was “obscenely good.” She cried in the walk-in; I pretended not to notice.

My mother was right about one thing: I did not crawl back.

Part III — The Ledger and the Visit

Back in 214, my father dozed. His mouth made a small open shape that was almost childlike. The television whispered an old movie where men always said the right thing on time. I sat with the wooden box in my lap, the photograph of my mother burning through the air.

“Tell me about her,” I said when he woke.

He looked at me as if a message had just been delivered from a great distance. “She wanted a yellow kitchen,” he said. “I said it would look like a lemon. She said ‘Exactly’ and painted it herself while I was at work.”

“You repainted it beige when she died,” I said.

He nodded. “Beige makes cowards of men,” he murmured, and I laughed in the way you laugh when grief finally decides to tell a joke.

He told me other things then, quiet and late. About a son who died before Clara and a hole that grief carved in him so wide he thought shouting could fill it. About a debt he owed to the wrong men and the right man he took it out on. About a night during a storm when he wanted me to beg so he could feel large. About the first time he knew he was small.

“I can’t ask you to forgive me,” he said.

“Good,” I said. “You wouldn’t know what to do with it.”

He smiled. “That’s my girl.”

“I’m not your anything,” I said automatically, and then softened. “I am a girl who survived you.”

The next day, Clara came. She looked like memory and a different life—older, resolute. She hugged me in the hallway like someone who no longer assumed an embrace would be accepted. We sat with him until the light on the walls looked like a lake at dusk.

“He did one good thing,” she said after a while. “He put the house in our names—ours—not theirs—when he sobered up. I sold it. I sent the money to the shelter you lived at—the one Mae told me about.”

I blinked. “You asked Mae about me?”

“Every year,” she said, eyes shining. “She told me when you were okay. She never told me more because she was protecting you from me… in case you didn’t want me.”

“I always wanted you,” I said.

We sat in the awful, lovely we of sisters who lost the same house at different times.

When we walked out of Meadow Ridge, Dr. Finch handed me a pamphlet about guardianship. “No pressure,” he said. “But he does better with visitors. The mind likes a witness.”

“I’ll keep coming,” I said, surprised by the truth of it.

On the way home, I stopped at Mae’s. The bell over the door invented a new pleasure every time it rung. She looked exactly the same—apron, hair escaping its clip, kindness like a habit she’d never break.

“You hungry?” she asked.

“Always,” I said, sitting in the back booth.

She put stew in front of me without asking. “You look like a person who chose not to set herself on fire to keep other people warm,” she observed.

“I’m learning,” I said, and took a spoonful.

“Good,” she said. “We don’t serve martyrs. They never tip.”

Part IV — The Blizzard Again, But Different

Winter came early that year. On the day meteorologists named the storm, the bakery lines curled around the building because Portland forgets that snow is water until it’s on our sidewalks. I stacked loaves, laughed with strangers, watched a woman cry over a crust because it tasted like her grandmother’s house.

Meadow Ridge called at noon. “He’s restless,” Dr. Finch said. “As if he can hear the snow through the insulation.”

I went.

The window in 214 framed the same old fir, its branches clotted with white. My father watched it like it might move.

“Blizzard,” he said.

“Yeah,” I said.

“You remember the one,” he started, and then stopped. He swallowed the rest of the sentence like a pill.

“I remember,” I said. “I walked to Mae’s. She gave me stew.”

He smiled. “You always did find the people dressed like kindness.”

“You kicked me out,” I said because truth should not go unsaid when weather tries to make everything clean.

“I did,” he answered. “I thought if I made the world harder for you, it would teach you to… love me.”

“That’s not how anything works,” I said.

“I know,” he sighed. “I’ve had thirteen years to understand that you don’t get to control how someone comes back to you. Or if they do.”

We listened to the snow press its body against the building. In another room, someone was playing an old holiday song on an out-of-tune piano. It wasn’t good. It was better than good.

Dr. Finch brought us hot chocolate in paper cups. “Against the rules,” he whispered, “but I like breaking those for the right people.”

“You should put that on your brochure,” I said, and he laughed.

“I wanted you to come crawling back,” my father said into the steam. “You didn’t.”

“No,” I said. “I learned to walk.”

He nodded toward the window. “Good boots?”

“The best,” I said, and we both laughed. It was a shabby, perfect sound.

He drifted. I tucked the blanket around his shoulders. His hand caught my wrist. It was a fragile clutch, more ask than capture.

“I’m sorry,” he said, voice barely there.

“I know,” I said. “I’m still not setting myself on fire.”

“I wouldn’t ask you to,” he whispered. “Not anymore.”

On my way out, Dr. Finch walked with me to the vestibule where the heat met the weather like enemies who decided to date. “He’s been better,” the doctor said. “When you come.”

“I’m not forgiving him,” I said. “I’m… rewriting my weather report.”

He smiled. “That’s more than medicine.”

The snow was already ankle-deep. The sky had that odd brightness storms bring when they steal the sun and offer a neon white instead. I pulled my hat down, tucked my scarf into my coat, and stepped into it. The cold kissed me hard in the face—the kind of kiss that reminds you you’re alive.

At the corner, I noticed a girl of maybe sixteen standing in a doorway, trying to look both invisible and brave. No hat. Courier bag. Hands bare and red.

“You okay?” I asked.

“Yeah,” she lied. “It’s just—you know—bus is late.”

“Yeah,” I said. “I know.”

“You waiting for someone?” she asked.

“No,” I said. “I’m going to Mae’s.”

“Makes good stew,” she said, and the surprise made me laugh.

“Come on,” I said. “I’ll buy you a bowl.”

She hesitated the way survivors always do when an offer might be a trap.

“Mae doesn’t serve traps,” I added. “Only kindness. And sarcasm.”

She smiled then—a small, reluctant sunrise. “Okay.”

We pushed the door open together. The bell invented a brand-new sound for the occasion. Mae looked up, assessed the scene, and slid two bowls onto the counter as if she’d been expecting us all day.

“Sit,” she commanded. “Don’t argue.”

We obeyed.

I watched the girl wrap her fingers around the mug and felt a memory unfurl without barbs. I thought of my mother’s certainty that I would come crawling back. I thought of the way perseverance can calcify into pride and how easily pride can become the only coat you own. I thought of my father’s hand, paper and cold, trying and failing and trying again to be gentle.

I didn’t crawl back. I didn’t cut everyone off in a blaze either. I learned something messier. I learned that a boundary is a door with a lock and a bell. It can stay closed to people who repeat harm. It can open for the ones who finally knock instead of kick.

The girl ate like I had—quickly, gratefully, eyes darting with animal scans for safety. “I’m Ellen,” I said when her spoon slowed.

“Juniper,” she answered, surprise at her own honesty flickering through her eyes.

“Nice to meet you, Juniper,” I said. “This blizzard doesn’t have a name yet. I think that’s rude.”

She laughed—the best sound I’d heard all day. Mae slid her a slice of pie without comment.

When the snow eased into a civil fall, I walked back to the bakery. Inside, the glass fogged up from heat and breath. I wrote a sign and taped it to the door.

Blizzard Special: If you are cold, hungry, or lonely, you are our guest. No charge. No questions. Yes on butter.

People think there’s one kind of closure: a slammed door. I’ve learned there’s another: the kind where you choose what cracks stay open to let in warmth, and you choose how loudly the past is allowed to knock.

Three days later, the sky remembered blue. My father remembered a song and hummed it badly. I remembered that forgiveness is not a gift to someone else so much as a permit to yourself to stop living where the hurt happened.

When Clara called to say she was baking the lemon bars our mother used to fake and asked if I wanted to come over and teach her to ruin them properly in our own kitchen, I said yes. We didn’t invite Patricia. Not yet. Maybe not ever. The door could stay locked and the bell could still ring for other people.

At 6:47 a.m. this morning, my phone rang again. Same unknown number from last week. I smiled and answered.

“This is Juniper,” the voice said, shy. “I got the job at the hotel. I put your name as a reference. They said… they said you were the kind of person who didn’t let people freeze.”

“Good,” I said. “That’s the whole business model.”

When I hung up, the winter light had that particular shine it sometimes gets on the morning after a storm: unearned, ridiculous, kind. I put on my boots. I walked to Meadow Ridge with a bag of cinnamon twists that made nurses grateful and administrators forgiving. I sat in 214 and handed my father a piece. He took it cautiously, like kindness might be a trick.

“It’s not,” I said, reading his face. “Not today.”

We ate. It was quiet. The good kind.

He looked at me once the way a man looks at a horizon he can still get to if he keeps walking.

“You didn’t come crawling back,” he said.

“No,” I said, and smiled. “I opened the door on my side and let winter happen on yours.”

Outside the window, the last of the storm slipped from the fir in clumps, falling and breaking and shining.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. My parents treated me like a maid, until at my grandfather’s funeral…

My parents treated me like a maid, until at my grandfather’s funeral… Part I — The Smallest Room My mother…

CH2. At Dinner, She Smirked: “My Ex Just Texted – I’m Meeting Him For ‘Closure’ Tomorrow.” I Just Nodded: “That’s Thoughtful.” The Next Morning, Her Bags Were Professionally Packed, The Locks Changed, And A Moving Truck Waiting. When She Came Back From Her “Closure” Meeting… She Realized I’d Already Closed Everything…..

At Dinner, She Smirked: “My Ex Just Texted — I’m Meeting Him for ‘Closure’ Tomorrow.” I Just Nodded: “That’s Thoughtful.”…

CH2. Parents Told Me, “Skip Thanksgiving — We Need Space.” But Their Regret Came Quickly

Parents Told Me, “Skip Thanksgiving — We Need Space.” But Their Regret Came Quickly Part I — The Message The…

CH2. My Daughter Betrayed Me… But My Late Husband Saved Me

My Daughter Betrayed Me… But My Late Husband Saved Me My daughter thought she could take everything—my beach house, my…

CH2. My Family Skipped My Child’s Surgery, Then Demanded $5,000 — and Called the Bank When I Laughed…

My Family Skipped My Child’s Surgery, Then Demanded $5,000 — and Called the Bank When I Laughed… Part I —…

CH2. The Family Of My Daughter-In-Law Pushed My Grandson Into The Lake… But They Didn’t Know My Brother

The Family Of My Daughter-In-Law Pushed My Grandson Into The Lake… But They Didn’t Know My Brother Part I —…

End of content

No more pages to load